Whyalla, Hunter Valley, Latrobe Valley: Like Trump’s heartland, blue-collar workers in our regions are hitting back at city elites

In our regions, there’s growing anger at city elites driving climate targets at the expense of jobs. Across four states, here’s what these silenced Aussies want you to know.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Coal is not a dirty word in the mix of wines and mines, the gentility and the grit, of the Hunter Valley in NSW, where statement estates nestle between open cut mines, and rail trucks rattle back and forth to the world’s largest coal port of Newcastle.

Coal brought prosperity to the region. Why would coal’s taboo status in the big cities resonate in parts where the federal government earlier this year approved the extension of a coal mine lifetime until 2050?

Here, the ALP member, Daniel Repacholi, is a former coal industry worker. There is no anti-coal messaging in his words – if there was, his local political career would be over. Here, instead, coal is routinely referred to as “black gold”.

Fossil fuel is not an abstraction in the Hunter. It is a way of life.

The former ALP member, Joel Fitzgibbon, speaks of coal’s enormous future, pointing out that resource exports help pay for the kinds of imports we no longer manufacture in Australia.

The realities of energy understanding in these regions, whether it’s Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, South Australia’s Whyalla, or northwest Queensland’s Richmond, sound foreign in the capitals.

Regional perspectives get overlooked in the vaulting pursuit of the transition to renewables. The historical engine rooms for Australia’s wealth feel trapped in flux, and more than a little neglected, in the high-minded rhetoric of climate change. Around these parts, talk of less carbon tends to produce more cynicism.

It’s the kind of jarring disconnect identified in Donald Trump’s election win in November, perceived to be in part a pushback against the city elites and their woke approach to climate change – at the expense of local manufacturing and jobs.

Fitzgibbon believes that humanity has contributed to a changing climate. For years in federal parliament, the former federal minister knitted the conflicting views of his party and his coal-driven electorate.

He suggests the US result might embolden those in the regions who are already sceptical about the breakneck pace – and tone – of energy transition in Australia. They may be asking, as he puts it: “Why do we need to do so much and take so much risk with our jobs and our livelihoods?”

“In the capital cities, you have very, very few people who rely upon the fossil fuels industry for their livelihood,” he says.

“But in the regions you have an enormous amount of people and families relying on fossil fuel industries for their household income and their livelihood.

“You have a contest of ideas there between the regions and the capital cities. It’s a difficult one for any politician or political party to manage.”

NSW’S COAL HEARTLAND

Max Tolson came home to Broke, an idyllic Hunter Valley hamlet with a catchy name, a dozen years ago with wife Bernadette, to grow vines, offer glamping at their Broke Estate, and keep cattle.

It’s some of the richest farming country in the nation. But it’s hard. Frosts and bushfires feature. In the last of the regular floods, in 2022, Tolson lost fencing and the vineyard.

Today, the flies buzz, thousands of them. The gums sag in the late afternoon haze. It’s 35C when Tolson, 72, turns up on his quad bike with his slightly battered and very loved sheep dog Baxter.

Tolson likes a chat. Turns out that he knows rather a lot about energy questions, both as a farmer and as a neighbour of Glencore, one of the local mining giants. He is also a land specialist who has worked in renewable and transmission line developments.

He can speak to the regional/city divide on climate change, and the perceived shortcomings of renewables – mostly the exorbitant price.

“I know what the costs are,” he says. “And when the average punter that has to pay for it all realises what the costs are, they’ll say why weren’t we told?”

But Tolson has learned to stay quiet when some city folk move to the Hunter.

“People from the city who have come in mainly in the tourist wine side of things think like city people – and hate coal. The rest of the community makes a living out of coal and therefore likes coal.”

He finds it easier to disengage.

“People who are very emotionally, philosophically attached to renewables and wokeness and their view of the environment, you can’t argue with them,” he says.

“They go into meltdown. And they will not tolerate anyone else’s views. Why put yourself through the pain?”

Down the road, at Wollombi, Chris Brooks’ then pub was submerged in the same 2022 flood.

Here, he explains, the joke goes that Wollombi is two hours away, and 200 years behind, Sydney.

Cynicism greeted an anti-fossil fuel protest of the Port of Newcastle a few days earlier – chatter settled on their supposed use of gas-fired barbecues on the foreshore. Earlier in the day, the NSW Government warned that warmer weather might trigger power blackouts in Sydney.

Amid the roar of cicadas, Brooks says there is a local acceptance that coal’s dominant place will end. The pubgoers around here are more divided on nuclear than coal.

“We’re going hell for leather down the renewables (path) and that will be the right thing, eventually,” he says. “But I just don’t know if our technology at this moment is enough. Are we throwing out the baby with the bath water?”

SA’S STEEL CITY

South Australia’s Whyalla can’t go back. Built on frontier daring, it bloomed for generations for its steelworks and shipping yards. But it seems unclear how it will go forward.

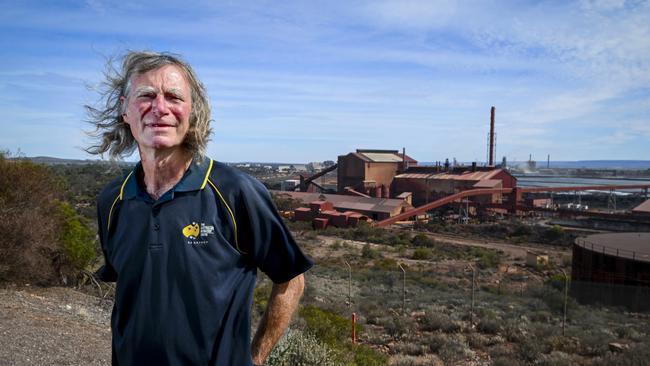

Marty Hilton is standing where the town began as a tiny work camp – Hummock Hill – in 1901. A fierce north wind buffets his grey mane.

He’s 67, and about to retire from the steelworks to the northwest.

He once worked for an elevator company. They’re all gone now. His Dad worked for Holden. That’s gone too.

“It’s really changed,” he says. “There is hardly anything that we make nowadays. It’s a shame because, like, I’ve worked at the same place for 45 years, so I’ve got all the benefits of that.”

Health food store owner Kate Dickeson, who has run Simply Good Health for 18 months, explains that she has given up.

“It was good,” she says. “Things were going great. And then the last six months, quite terrible – to the point where I’ve chosen not to renew my lease next year. Just due to the uncertainty in town.”

Does she have a message for Prime Minister Anthony Albanese?

“Please listen to business owners in these towns doing it tough,” she replies.

“Take action quickly. We just feel it’s carried on too long. Just listen. Please listen.”

Down the road, Jim Watson, 49, is managing director and principal designer of Metric Consulting Engineers.

He wonders, given the downturn, how specialised and experienced local capabilities can lift to meet the needs of industry here.

“There’s a gap there,” he says. “How do we forge that gap?”

He vividly describes an ocean of business and industry people in floaties, while sharks circle underneath.

“We kind of need someone to come and scoop them up in the boat, like the federal government boat or the state government boat, and bring them to shore,” he says.

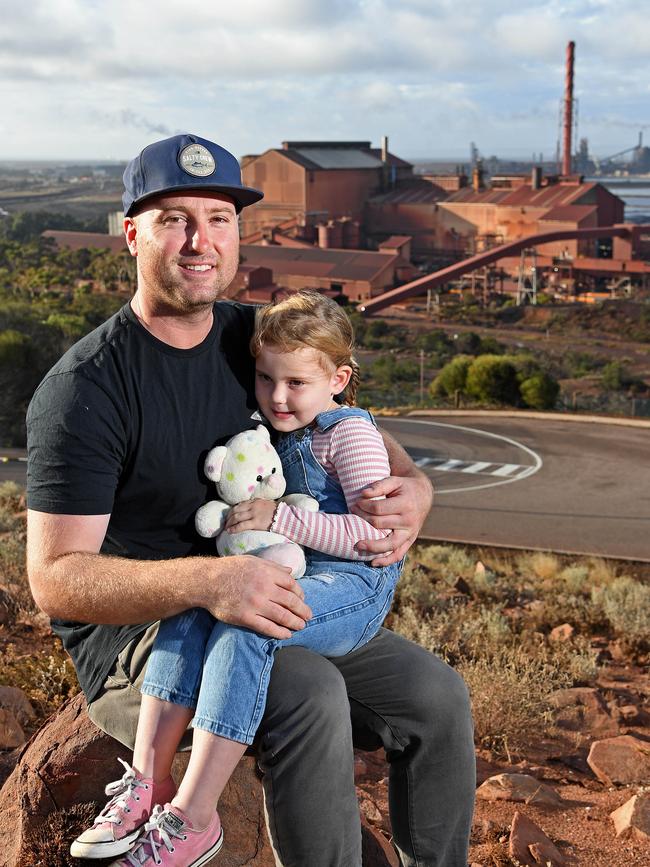

Self-employed contractor Alex Manners, 32, says that coal does not get the big-city respect that it warrants. On steelmaking, and manufacturing, he identifies a waste of our raw resources, “of just putting them on a ship and sending it over to China for them to make stuff out of”.

There has been a worldwide trend in recent months to abandon green hydrogen projects.

But Whyalla’s ALP member, Eddie Hughes, points to a future built on hydrogen produced from a $593m government-owned plant as the key for fully fledged green steel manufacturing.

“When it comes to the iron making process, we’re not going to step into a green hydrogen future tomorrow,” Hughes says. “So we are going to need natural gas as a bridge to that future.”

VICTORIA’S VALLEY OF COAL

Dale Harriman has been mayor of the Latrobe City Council for about five minutes. But he’s keenly aware that he faces many energy questions with few energy answers.

He speaks of Morwell, in the valley a couple of hours southeast of Melbourne, the once thriving town that died a little when the Hazelwood coal-fired power station closed abruptly in 2017.

He frets for Moe, the nearby town which might slump when Yallourn power station, which inherited the “dirtiest” Victorian power station title after Hazelwood closed, is scheduled to close in 2028.

In Morwell, a few thousand jobs disappeared, in a flow-on effect which can be roughly gauged by all the empty shopfronts on Morwell’s main street today.

There was lots of talk about replacement industries after Hazelwood. None flourished.

There was no like-for-like jobs. The population stagnated; many of those with fossil-fuel industry skills found work in WA or NSW.

Morwell lost its community glue – the volunteers, the coaches, the umpires who bring people together. As Harriman puts it: “We’re the most disadvantaged area in the move for a zero emissions policy in Australia. People are angry. They feel like they are not listened to.”

The Latrobe Valley was Victoria’s powerhouse of coal for generations. But uncertainty has mired its future since the 1990s, when the State Electricity Commission was privatised. It’s not even clear when Yallourn will close – it may remain open beyond 2028 due to gas shortages and renewable energy project delays.

There have been no lack of ideas. Coal for hydrogen. A really big battery. High efficiency low emissions coal technology.

Solar farms have been canvassed, as have offshore wind farms, though local rumour dictates that state government bumbling will prolong the timelines. “We need logical steps,” says Harriman. “Not ideological ones. Going to 100 per cent renewables just doesn’t make sense in Australia.”

This leaves nuclear, which appears to be growing as a popular alternative in the Latrobe Valley.

The area has been identified by the federal Opposition as a logical site for reactors.

Yet time is running out. Can wind, solar or nuclear plug the gaps left by coal? And, if they can, could they be operating before unemployment and cost-of-living pressures further ravage this proud region of diminishing returns?

QUEENSLAND’S ENERGY HUB

You may have noticed Queensland’s longest serving mayor John Wharton, 71, who has led Richmond Shire Council west of Townsville for 27 years, earlier this year.

In opting into the Australia Day debate, he spoke of “all that bullshit” of federal politicians who pander to big city voters who never visited the regions.

Today, in adopting a similar tone, he wants to talk about bureaucrats, and how unhelpful they have become, including with climate targets.

“It’s become the culture in a lot of these government departments …‘we will tell you what’s best, you don’t know what’s good for you’,” Wharton says.

“It doesn’t work, it’s never worked.”

The construction of the 1100km transmission line CopperString, for which costs have reportedly blown out from $5b to $9b, will have economic benefits for Wharton’s region and lift the feasibility of wind and solar farms.

It would also connect the North West Minerals Province, west of the Richmond Shire, to the main energy grid, and improve the likelihood of $500bn in critical minerals deposits being mined.

The region is in huge demand for energy. It has been reported some of these mines are reliant on diesel in order to maintain production.

Wharton believes that CopperString would provide huge opportunities for his region.

But he says he important questions on regional energy policy are being ignored on a broader scale.

Late last year, the recently ousted Labor government in Queensland pushed through ambitious legislation to reduce 75 per cent of emissions by 2035.

“Everyone was quite excited when the first wind farms turned up,” Wharton says.

“They sort of said, ‘okay, we’ll pay you $40 grand a year to have a wind turbine, you’ve got 10 there, that’s $400 grand a year you’re going to get … so the landowners were quite happy about that.

“But then what happens is the waste from the turbines, if they break, someone’s got to deal with them. Who is going to look after that waste?”

CITY-REGIONAL DIVIDE

After generations of assumed prosperity, the engine room regions of Australia feel overlooked.

The fossil fuel triggers that fuelled so many local financial ecosystems have been closing. The prevailing view is that big city politicians don’t seem to care about the effects.

There is an us versus them psychology – the haves in their city offices with their high-minded ideals, and the self-described have-nots in the bush who feel like they will pay for those grandiose visions whether they are achieved or not.

Perhaps the Hunter’s Max Tolson puts it best:

“The difference between rural people and city people is that rural people generally, certainly those who rely on agriculture, are harder working, lower income people.

“And people from rural or regional areas who are involved in mining know where their income comes from.

“But the people in the city are distant from it, they only see government largesse that’s possible via royalties and taxes. And that’s the reason for the divide.”

Originally published as Whyalla, Hunter Valley, Latrobe Valley: Like Trump’s heartland, blue-collar workers in our regions are hitting back at city elites