From petty crim to jailbreak killer: The story of Ronald Ryan, Australia's last man hanged

SOME believed him innocent, jurors who found him guilty still didn't think he should hang, but the Premier was determined that Ronald Ryan would go to the gallows. Australia's last-man hanged faced his fate "like a small child who had composed himself into calm bravery". "Whatever you do, do it quickly, " he told the hangman.

NSW

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SOME believed him innocent, jurors who found him guilty still didn't think he should hang, but the Premier was determined that Ronald Ryan would go to the gallows. Australia's last-man hanged faced his fate "like a small child who had composed himself into calm bravery".

"Whatever you do, do it quickly, " he told the hangman.

Our criminal history: Shark coughs up gruesome clue in bizarre murder case

Picture specials: Policing in the '50s | Policing in the '60s | Policing in the '70s

The following is an extract from the book Noose by Xavier Duff.

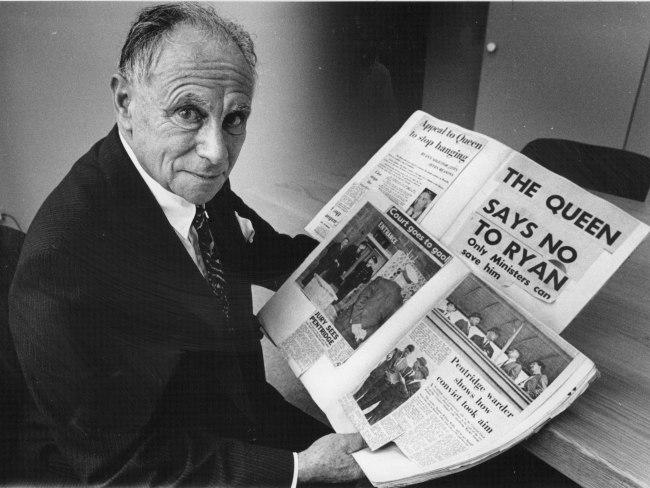

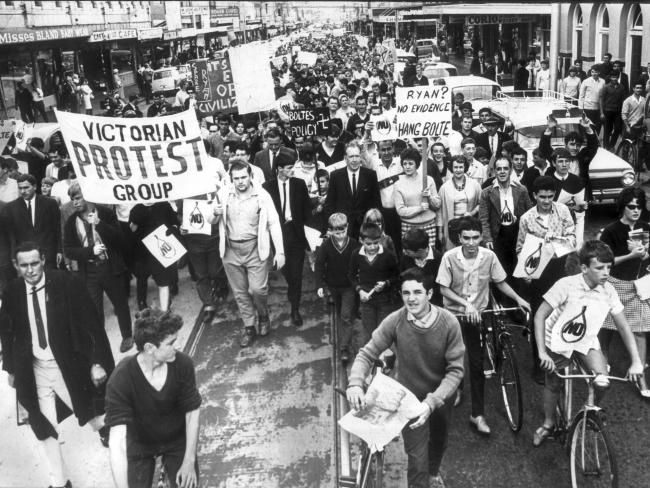

THE day the last man was hanged in Australia dawned hot and clear. The warm breath of a northerly began to stir, ruffling the hair and rattling the nerves of a thousand protesters gathered outside the gates of Melbourne’s Pentridge Prison.

The night before, even more of a crowd — a rowdy, hostile throng of 3000 — had milled about the prison’s bluestone walls, chanting anti-hanging slogans and listening to impassioned impromptu speeches, as if they could stop the inevitable by sheer force of will.

Gradually, things had got tetchy. Some of the demonstrators goaded the police, and a few scuffles broke out. The coppers, fearing the crowd would storm the entrance, pushed back, and the mob resisted. Before long, protesters were being arrested and hauled away, not least among them Clyde Holding, the leader of the Labor state opposition. Eighty-seven people were charged with offensive behaviour and assaulting police.

As the night wore on, most drifted away, but some returned in the morning.

It was 3 February 1967. By 7am, the official witnesses had arrived, including about fifteen journalists, who assembled in D division, standing behind a roped-off area about thirty yards from the gallows. The only concession to the condemned man’s dignity would be a green tarpaulin hung below the trapdoor so that the assembled group could not see his body swinging. They would only see him disappearing through the trap, like some macabre magical act.

At 7.58am, the Supreme Court sheriff and the prison governor walked into the death cell opposite the trap, followed by the hangman, a tall, lanky man, bizarrely wearing a boilersuit, welder’s goggles and a green cap to disguise his identity. Inside the cell, the condemned man wore a grey, open-neck shirt and blue-grey denim trousers. His hands were cuffed, his arms bound and a hood of unbleached calico placed on his head just above his eyes.

At precisely 8am, the hangman walked his client onto the trap. As he did so, trams and trains came to a halt all over Melbourne, workers on building sites downed tools for two minutes in protest, and people stopped what they were doing to reflect on what was about to take place.

Journalist Patrick Tennison described the condemned man as ‘white but impassive, his thin lips together, but not clenched. His face was strangely like a small child who had composed himself into calm bravery just before the doctor gives a needle.’

The hangman trussed his legs, dropped the noose, which hung from a beam, over his head, adjusted the position of the knot under his left jaw and drew it tight. Looking up at the hangman, the condemned man whispered, ‘God bless you. Whatever you do, do it quickly.’

And with that the goggled executioner gave the rope one last wrench, pulled the hood over the man’s eyes, deftly stepped back and pulled the bolt.

The thud as the hanged man reached the bottom of his drop reverberated around the cathedral-like space. The noise sent a flock of pigeons flying from one of the towers in alarm, signalling to the man’s supporters outside that the deed had been done. They bowed their heads. Many cried.

Some newspapers refused to publish their reporters’ accounts of the hanging in protest. But most of the public did not need convincing that state-sanctioned murder was a hideous spectacle and a relic of the past. The brutality and inhumanity of this act ensured it would be the last.

*

For the dubious honour of being the last man to hang on Australian soil, one would expect a heinous crime to match the barbarity of the punishment. After all, no-one had been hanged in Victoria in sixteen years. The public distaste for capital punishment had grown so strong that politically it was unacceptable to send anyone to the gallows — even the worst murderers. The tipping point for hanging to be removed from the statutes altogether had been reached.

At this time, Queensland was the only state to have abolished capital punishment for all crimes, a move taken as early as 1922. The last execution in Queensland was in 1913. All the other states and the Northern Territory retained it but rarely used it.

Tasmania was effectively a no-hang state from 1933, when a Labor government commuted all the outstanding death sentences, but there was one notable exception. In 1945, Frederick Thompson was sentenced to death for the rape and murder of a young girl named Evelyn Maughan, who had been abducted on her way to church in Hobart. Three months later, her body was found on top of a grave in a disused cemetery. With public anger running high over the crime and an election in the air, the Labor government rejected party policy and refused to commute the death sentence. On 15 February 1946, Thompson became Tasmania’s last visitor to the gallows and the only person ever to hang there on Labor’s watch. Even so, the death penalty was not finally abolished until 1968.

In New South Wales, capital punishment for murder was abolished in 1955, but it was retained for piracy and treason. It was abolished for those offences as well in 1985; by then, the state’s last hanging was 45 years in the past. There had been more recent hangings in South Australia and Western Australia in 1964, but South Australia abolished the death penalty in 1972 and Western Australia in 1984.

Although Victoria still had the death penalty in 1967, all 35 people found guilty of murder since 1952 had had their death sentences commuted. So who was this man to warrant the ultimate punishment? A serial killer who tortured and terrorised his victims? A man whose crimes were so disgusting that even the most fervent anti-hanging activists would temporarily suspend their opposition to capital punishment?

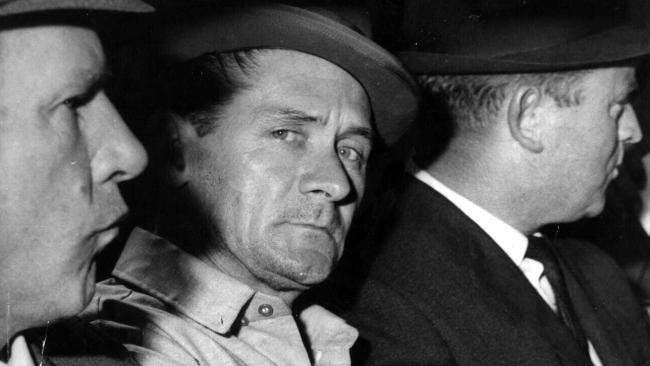

Well, no. As bad as his crime was, Ronald Ryan was not in that league. He was a small-time thief whose worst crime before 19 December 1965 was to blow up a safe in a butcher’s shop in the middle of the night. He loved his children and his wife, who tried her best to love him back, despite the difficulties of being married to a crook. He was certainly no role model. But did he deserve to hang for the murder of a prison warder, shot in the heat of a desperate escape bid?

Even if he was guilty — a matter that is still the subject of spirited debate — it was most likely the result of a last-second brain snap, and certainly not of premeditated intent. But one man was determined to see this small-time thief hanged.

Henry Bolte, the hugely successful long-serving premier of Victoria, was a dyed-in-the-wool social conservative who believed in traditional values and institutions, respect for authority and hierarchies — and capital punishment. Bolte held a torch for capital punishment as few others did by the 1960s.

But he was sophisticated enough in his thinking to believe capital punishment should be reserved for the most heinous crimes. In fact, he had presided over the commuting of many of the 35 death sentences passed between 1951 and 1967, because he and his Cabinet believed they were not warranted. In Bolte’s view, hanging was only justified for particularly brutal murders, those involving the sexual assault of children or — crucially for Ryan — murders of police or prison guards.

“I don’t believe in capital punishment for crimes such as when a man kills his wife or vice versa: that’s more or less fair game,’ Bolte said. ‘It happens every day of the week, usually on the spur of the moment, as much as by accident as anything else.’

But he believed the murder of a person in uniform whose job was to keep public order deserved the ultimate penalty. That was why Ryan must hang.

Usually, Bolte did not care about public opposition. For the firebrand who once said that striking teachers ‘could walk up and down until they’re bloody well footsore’, public opprobrium was water off a duck’s back.

The Ryan hanging, though, provoked the bitterest public debate Bolte ever faced. He received death threats and abuse that would have wilted even the strongest conviction. He had to have his phone number delisted, his home guarded constantly by police, and extra security employed wherever he went in the months leading up to that hot February day.

*

Ronald Ryan’s journey to the gallows began quite late in life. His first recorded conviction was not until he was 31. Until then, he had led a relatively responsible, hardworking existence, overcoming a poor family life in Melbourne and several years in an institution.

Ryan was born in 1925, the son of ‘Big Jack’ Ryan, an Irish coal miner who was eventually unable to work because he was slowly dying from a lung disease. There was little joy in the Ryan household in Mitcham. Jack was occasionally violent and abusive, and the family were often short on essentials because much of his invalid pension went on booze. Child welfare were frequent visitors to the Ryan household. In 1936, Ronald, aged 11, was made a ward of the state and sent to the Salesian Brothers home for wayward boys in Rupertswood, outside Sunbury; a year later, his sisters Violet, Irma and Gloria were declared neglected and sent to the convent of the Good Shepherd in Abbotsford.

At Rupertswood, Ryan was a popular kid and gifted sportsman, captaining the football and cricket teams. He was at the home for almost three years, but he does not appear to have been especially happy there. After several failed attempts to run away, he finally escaped at the age of 14, ‘jumping the rattler’ to Balranald in south-western New South Wales, where he joined a half-brother from his mother’s earlier marriage.

Ryan got work cutting railway sleepers and burning charcoal. By all accounts, he conducted himself well. He continued with his sport, winning trophies for bike riding and athletics. He sent money to his mother, who was still nursing his sick father, but his dream was to bring his sisters and mother together again. According to journalist Norman Hetherington, by the time Ryan was 18, he had saved £200 — enough money to persuade the authorities he could support his sisters. He came to Melbourne and took them out of state care, then moved the girls and their mother to Balranald, where they lived in a rented cottage. His father stayed in Melbourne and died a year later. The girls went to the local convent school, and family life for once was what it should be.

‘We did not think much about it at the time,’ his sister Irma recalled in a newspaper interview. ‘We took everything for granted the way kids do. But we know now that Ron missed out on all the fun of teenage life, working to look after us. He’s never reminded us of it. He was out in the bush most of the time, and when he came home he gave his spare time to running the Balranald Boys Club. That was his one big interest apart from the family.’

Ryan found love in Balranald, but the girl he hoped to marry became engaged to someone else while he was working in Gippsland for a while. Devastated, Ron moved back on his own to Melbourne, where he found work as a storeman. A year or so later, he found a new love, Dorothy George. Privately educated, Dorothy was the daughter of a former mayor of Hawthorn, but had rebelled against her wealthy family. She and Ryan were married in St Stephen’s Anglican Church at Richmond on 4 February 1950. Ryan, who had been brought up Catholic, converted to the Church of England to marry her.

Every summer, Ron worked cutting timber deep in the bush at Matlock. He would stay out in the bush for two weeks at a time, coming home to Melbourne every second weekend to see the family, which grew to include three daughters. By 1952, Dorothy and the children had moved to Noojee, a timber town closer to Ryan’s work.

Ryan’s employer, logging contractor Keith Johanson, was impressed with the young man’s work ethic and his ability to lead a group of his fellow workers

‘This Ryan is a cut above most of these fellows,’ Johanson said in a character reference.

But Ryan was beginning to wander off the path of responsibility. His first encounter with the law came in 1953, after his rented house in Noojee was burnt down while he was in Melbourne. When the arsonist was caught, he claimed that Ryan had put him up to it to claim insurance money. Ryan was charged with arson, but acquitted.

In the years that followed, money became increasingly tight. Ryan had developed a gambling habit. In 1956, he was convicted of passing forged cheques on two separate occasions, but he managed to get off on good behaviour bonds.

He continued to work at various jobs, among them running a greengrocer’s shop in Camberwell, but he had developed a taste for the good life that cost more than his meagre wages. He was seduced by the prospect of quick money from gambling, but it was easier said than done. A friend recalled that he once walked home from the Melbourne Cup stone broke.

Often in debt, he began to take thieving more seriously. He led a gang of men who broke into shops and factories to steal cash and goods that he would try to sell on the black market. In early 1960, he and his accomplices were arrested for multiple break-ins between July 1959 and March 1960, in the course of which they had stolen suits, motor mowers and cigarettes. On the day of their arrest, the gang escaped from the city watch-house, but they were soon rounded up. In June that year, Ryan pleaded guilty to eight charges of breaking and entering and one of escaping from legal custody. His lawyer said he would not plead any mitigating circumstances. His little escapade added a year or two to his sentence, giving him eight and half years to contemplate where he had gone wrong. Ryan did not blame anyone but himself.

In Bendigo jail, he became known as a model prisoner. He set about studying for his intermediate and leaving certificates, which he passed with flying colours. Ryan was studying for matriculation when he was released on parole in 1963 with a glowing reference from the jail’s governor, Ian Grindlay.

Ryan tried to settle back into the straight life with his family. He took a clerical job, but it only lasted a couple of months. He then switched to house painting, but he was soon back to his old tricks. By now, he had added a new skill to his criminal repertoire — safe-blowing.

In early 1964, he was arrested for robbing a butcher’s shop. He was bailed and escaped to New South Wales, where he broke into a string of shops and factories. Police arrested him on his return to Melbourne, and in November 1964 he was convicted on several offences, including possessing explosives. Ryan now faced the depressing prospect of spending nine years at Her Majesty’s pleasure.

The one notable feature of Ryan’s relatively short criminal career was that he had never been charged with using violence. In fact, after one failed attempt to blow open a safe in a butcher’s shop in Mount Waverley, he left a note warning people to keep clear of the safe because there were unexploded charges there.

But his criminal life had worn thin for his wife, Dorothy. She could see no future for herself and the children unless she divorced Ryan. Ten months after he went to jail, she initiated divorce proceedings.

Inside Pentridge, Ryan had a lot of time to think about the prospect of his family falling out of contact while he was serving his long sentence. An eternal optimist, he looked for a quick solution. He cooked up a grandiose scheme in which he would escape from Pentridge, cash up by robbing some banks and flee to Brazil, then convince Dorothy to come with the children and join him. He chose Brazil because it had no extradition treaty with Australia. How hard could it be?

He spent many hours mapping the layout of Pentridge, watching the warders’ movements around the jail and studying their rosters. He came to the conclusion that it could be done — he could go over the wall.

He enlisted the help of Peter Walker, a 24-year-old villain who was doing twelve years for armed robbery, and convinced him that they could do it. Ryan made his preparations, believing they had nothing to lose.

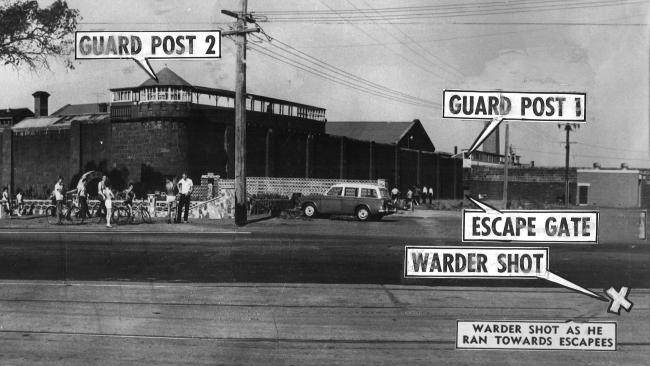

Just after lunch on 19 December 1965, a sunny, warm Sunday, he and Walker made their way to the wall of the B division exercise yard with a couple of bedspreads concealed beneath their shirts. Ryan had worded up some of the other prisoners, who rattled milk bottles to distract the warders.

Ryan and Walker scaled the five-metre internal wall with the help of some wooden benches, and jumped into the no man’s land leading to the external wall. Ryan picked up a grappling hook he had fashioned and hidden there earlier, along with two pieces of water pipe.

They tied the grappling hook to the bedspread ‘rope’ and used it to climb the wall, then made their way along the catwalk to the sentry box, where warder Helmut Lange was stationed.

Lange was wondering about all the noise coming from the exercise yard. He peered down over the wall, then turned around to see Ryan standing with the water pipe raised as if to strike him. Lange froze, and Ryan grabbed his M1 carbine from the rack.

Ryan cocked the gun and ordered Lange to open the outside gate, which led to Church Street and freedom. The warder pulled a lever, and then Ryan walked him to the tower, where Walker was waiting. The three went down the stairs to an officer’s cubicle, where warder Fred Brown was standing. As they passed, Ryan pointed to Lange and told Brown, ‘If you do anything, I am going to kill that man.’

Walker tried to open the gate, but it was still locked. Lange had deliberately pulled the wrong lever in an attempt to foil the escape.

‘Come on, we’re going back, and this time you better pull the right lever,’ Ryan growled. He marched Lange back up to the tower, the carbine’s barrel firmly wedged in his back, and ordered him to pull the right lever.

Ryan went back down the stairs and told Walker that the gate was open. As he passed the officers’ cubicle, he noticed a Salvation Army officer, Brigadier James Hewitt. Walker opened the gate, and Hewitt went out of it ahead of him. Sensing something was not right, Hewitt began to hurry off, but Ryan and Walker followed him.

Ryan grabbed Hewitt and snapped, ‘Come on, quick. Give us the keys of your car. We are taking you hostage.’

But Hewitt said he didn’t have a car. There were no obvious escape vehicles in the carpark, and the situation was becoming desperate.

Lange had already rung the front gate and given three blasts on his whistle to signal an escape in progress. Ryan saw one of the warders, William Bennett, looking down at the three of them. Bennett went to cock his firearm but it jammed. He pointed the rifle at Ryan anyway and told him to drop his weapon.

‘Drop the gun or we will shoot the man,’ Ryan yelled back.

According to Bennett, Ryan then used his carbine to hit Hewitt on the head. He crumpled to the ground, and the pair took off towards Sydney Road. Ryan later denied hitting the brigadier; he said he just pushed him away, and if he had hit him it was an accident.

Meanwhile, George Hodson, a long-serving warder, was returning from lunch when he saw Ryan and Walker struggling with Brigadier Hewitt.

‘What’s going on?’ Hodson yelled out from inside the wall.

‘There’s been an escape,’ Lange called back.

Unarmed, Hodson took off out the gate and began to chase the pair. Several warders rushed out to join him, while others took up positions in the towers, aiming their rifles at the escapees.

With the burly Hodson in pursuit, Walker ran towards the nearby Catholic Church, jumped over the churchyard wall and hid behind it. Ryan meanwhile had taken up a position on the intersection of Champ Street and Sydney Road, where he tried to stop passing cars by waving his carbine about.

Some kept going, and one tried to run him over, but eventually he managed to stop a vehicle containing a man and his wife. Ryan ordered the man out and slipped in behind the wheel, but the driver’s wife did not move, saying she wanted to get a coat and bag from the back. Eventually, she opened the door and got out.

Just then, a warder called William Mitchinson appeared at the driver’s window.

‘Righto, Ryan, the game is up,’ he said.

Ryan grabbed his carbine and pointed it at Mitchinson.

‘Right, stand back or you get this,’ he barked. He slid across the seat and got out the passenger door.

Meanwhile, in the churchyard, Hodson had caught up with Walker, who jumped up and ran towards Ryan. Hodson picked up Walker’s metal pipe and begin hitting him with it as they ran. According to a number of eyewitnesses, Ryan then raised his gun to his shoulder and took aim at Hodson, who was about thirty yards away. A shot rang out above the din of the traffic. Hodson raised his hands to his head and fell face-forward onto the tram tracks.

Ryan then managed to stop the driver of a Vanguard and ordered him out. Ryan and Walker jumped in and sped off. Another warder, Robert Paterson, waved down a car and asked the driver to set off after them, but he replied, ‘You follow it your bloody self.’ The escapees were on the move by the time Paterson persuaded another driver to help, and he soon lost sight of them.

There was little anyone could do for Hodson. He had been hit in the side of his body, the bullet passing clean through, and he died almost instantly. A woman who had been caught up in the confusion got out of her car and sat with him until the ambulance arrived.

News of the escape quickly spread, and the biggest manhunt Melbourne had ever seen was soon underway. Police swarmed the streets of the northern suburbs and set up roadblocks in a bid to tighten the net. The city was on high alert. People feared that the pair could appear over their back fence at any time or hijack their cars as they drove along.

The spectre of the fugitives hung over the city for days. The police raided the homes of known associates and underworld figures. Parents would not let their children leave home unattended, and picture theatres were empty. People jumped at shadows, and police had to deal with hundreds of false sightings of the pair. On 22 December, police descended on Swanston Street after someone reported seeing Ryan. It turned out to be a telephone linesman.

After the shooting, Ryan and Walker drove to Kensington, dumped their getaway car and stayed the night with a couple called Keith and Edna Hurley. The next day, they went to a flat in Prahran belonging to Mrs Patricia Puccini, who arranged for a friend of hers, Christina Aitken, to hide the two. Aitken took them to another friend’s flat in Elwood and asked her to put them up. She also bought dye so that Walker could change the colour of his hair. Aitken and her daughter Sharon stayed with the pair in the flat for two nights. Aitken said later that Ryan threatened her and the child if she tried to turn them in.

Ryan wasted no time pushing ahead with his grandiose plan to bankroll his escape to Brazil. On Thursday 23 December, he and Walker went into the Ormond branch of the ANZ Bank, carrying a revolver and the carbine Ryan took from Pentridge. They held up the bank, locked seven staff in the strongroom and helped themselves to £4500.

Witnesses said that the men referred to themselves as the Pentridge escapees. One of them — it is not clear if it was Ryan or Walker — indicated the carbine and said, ‘This gun shot a man a few days ago and I’ll use it again.’

By now, the Victorian government had announced a £5000 reward for information leading to their capture. The next day, Friday, Aitken and Walker drove to a used-car yard and traded in Aitken’s car for a panel van. They bought a shotgun on the way back.

That night, a group of people came back to the Elwood flat and had a few drinks. One of them was Arthur Henderson, a tow-truck driver who was Aitken’s boyfriend. Somehow, Walker and Ryan got the idea that Henderson was going to inform on them. Aitken pleaded with the pair that Henderson was harmless and just had a bit too much to drink.

Not long after this, Walker and Henderson left the flat to go and buy some beer. Walker eventually returned on his own. He took Ryan aside, and Aitken overheard their conversation.

‘Are you sure he’s dead?’ Ryan asked.

‘There was a pool of blood. His pulse had stopped,’ Walker replied.

Henderson’s body was discovered in a public toilet in Middle Park that evening. He had been shot.

Aitken and Puccini were later charged with harbouring the criminals and went to trial. Aitken said she had acted as she did because she was afraid for herself and her child.

Walker later confessed to killing Henderson, but said he did it in self-defence. As Walker told the story, he was worried that Henderson was going to turn them in and confronted him at the toilets while they were out getting the beer. There was a scuffle, and Walker drew his gun to fend Henderson off. They grappled with the gun and it fired, killing Henderson.

Earlier that day, a funeral for George Hodson was held at Springvale, attended by 200 prison officers. On top of the coffin was a cushion carrying a prison officers’ valour medal, which had been awarded posthumously for his bravery in trying to recapture Ryan and Walker.

After the Henderson shooting, the pair decided it was too difficult to remain hidden in Melbourne, so they had better head for Sydney. They went around to the Hurleys on Christmas morning and arranged for Hurley to drive to Sydney, buy a high-powered car and drive it back to Melbourne. Hurley, who claimed he was being threatened to help the pair, enlisted the help of his friend Norman Murray. They drove to Sydney on Boxing Day, returning with the car on 30 December. Murray also organised a flat at Coogee for Ryan and Walker to stay in when they arrived. While Hurley and Murray went on their mission, Ryan and Walker stayed at Hurley’s house with Edna, who Hurley later claimed was held as a hostage. Once they had the new car, Ryan and Walker left for Sydney around New Year’s Day.

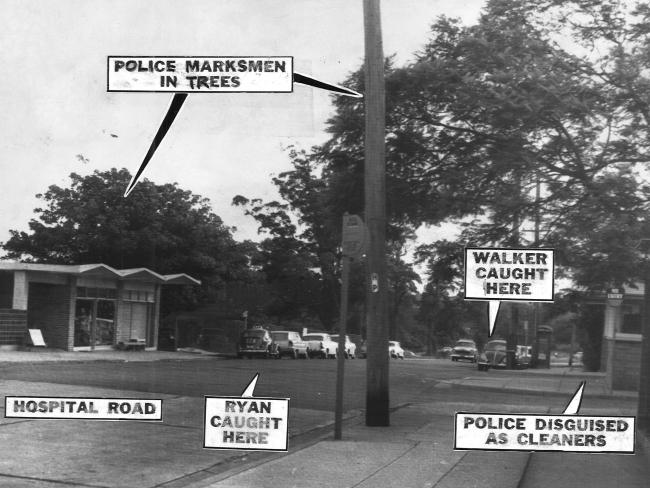

A few days later, Walker made contact with a young woman he knew in Sydney and arranged to meet her and her friend outside the Concord Repatriation Hospital on the evening of 5 January. It was a big mistake. The woman told police about the meeting, sparking one of the most elaborate stake-outs Sydney had ever seen.

Under the command of Inspector Ray Kelly, a team of 50 officers surrounded the area around the hospital well before the appointed time. They had a policewoman and another civilian woman standing as decoys for the two dates Ryan and Walker were expecting, so they would not be suspicious when they arrived. But the fugitives were half an hour late, and by the time they got there, the stand-in women had left.

With no sign of the women, Ryan got out of the car and walked to a public phone box to ring Walker’s friend. The phone was out of order, so he went into a milk bar and asked if he could use the phone there. The police surrounded the milk bar and grabbed Ryan as he came out. He had a .32 calibre revolver, but made no attempt to use it.

Other coppers had surrounded Walker, who was sitting in his car, and arrested him too. It was a textbook capture. In the car were cash, ammunition and several firearms, including the M1 carbine Ryan had taken from Pentridge.

Victorian detectives were soon on their way to Sydney to bring the pair back on a chartered flight. The whole city of Melbourne breathed a sigh of relief.

*

The coronial inquiry into Hodson’s death began on 3 February 1966. It kicked off one of the most intriguing criminal cases in Victorian history. The theories about what happened that sunny December afternoon have multiplied to rival those around the Kennedy assassination. Books, documentaries and dozens of newspaper articles have put forward different versions of what happened. In all probability, the truth will never be known.

The key witnesses at the coronial inquiry were prison warder Helmut Lange, Senior Detective Harry Morrison from the homicide squad, who brought Ryan back to Melbourne after his arrest, and John Fisher, who was with Ryan and Walker at Aitken’s flat the night Henderson was shot.

Lange told the coroner that he saw Ryan aiming at Hodson as he chased Walker along Sydney Road. He felt helpless and looked around, hoping another officer might be able to do something. ‘When I looked again at Ryan, he was still aiming at Hodson. Then I heard the sound of the shot and saw Hodson fall to the ground.’

Morrison claimed that on the plane on the way back, Ryan had said, ‘The warder spoiled the whole show. If he hadn’t poked his great [nose] into it he wouldn’t have got shot. It was either him or Peter. Hodson grabbed hold of Pete and hit him with an iron bar.’

Fisher, who knew Ryan from their days in Bendigo jail, said Ryan had told him he had shot Hodson. Ryan said the warder ‘had been in his way, and if anyone else had been in his way, he would have shot them too’.

The coroner found that Hodson was murdered by a gunshot wound inflicted by Ryan and committed him and Walker to stand trial for his murder. Even though Walker was not directly involved in the killing, the charge came under the felony murder rule: he was a partner in the crime of escaping, which led to Hodson’s shooting, and therefore was equally culpable.

The trial began on 15 March in the Melbourne Criminal Court before Justice Sir John Starke. A phalanx of warders and police surrounded the pair as they were escorted into the dock. Walker and Ryan both pleaded not guilty to the charge of murder.

The prosecution’s case was built around the fourteen or so eyewitnesses who saw Ryan aim the gun at Hodson as he chased Walker, and the testimonies of John Fisher and the detectives who claimed Ryan had confessed to shooting Hodson.

Detective Sergeant Kenneth Walters from the homicide squad said that after his arrest, Ryan told him ‘off the record’ that he had shot Hodson, but said he had no intention of doing so. The two of them just wanted freedom.

Ryan allegedly said of Hodson, ‘He caused his own death. In the heat of the moment you sometimes do an act without thinking. I think this is what happened to Hodson.’

Walters also claimed that Ryan had said, ‘I could have shot a lot more screws.’ But when Walters took his written statement, Ryan denied shooting Hodson.

Several witnesses, including warders Lange and Mitchinson, testified that they saw Ryan level the rifle at Hodson and heard a shot fired before Hodson fell. One claimed to have seen the recoil of the rifle as it nudged Ryan’s arm and a puff of smoke rose from the barrel.

A ballistics expert testified that the barrel of the carbine was dirty when it was retrieved from the car, suggesting it had fired a shot since it was last cleaned.

Despite the prosecution’s strong case, Ryan’s defence team, led by Philip Opas, had some powerful evidence on its side. Opas pointed out that Ryan was not the only one holding a rifle in the shooting position. Up in Tower 2, William Bennett had a rifle trained on Ryan, waiting for a clear sight to fire at him.

Meanwhile, at ground level, Warder Robert Paterson was about to squeeze off a shot at Ryan when a woman moved into his line of fire, so he raised the rifle and shot over her head. This was a key piece of evidence, because all of the witnesses claimed to have heard a single shot being fired. If both Ryan and Paterson fired shots, why was only one heard? To complicate matters, a newspaper report the next day had said that Warder Bennett also fired a shot, though he later denied it.

Opas also challenged the ballistics evidence, which he argued was inconclusive. The barrel had not been examined for gunpowder residue and could have simply become dusty as it sat in the back of the car during Ryan’s days on the run.

Crucially, the bullet that hit Hodson and passed straight through him was never found, nor was the empty shell. Either would have made it possible to identify the rifle and prove beyond doubt if the shot came from Ryan or a warder. In fact, Ryan argued he had kept the carbine just in case he was accused of the shooting so it could be proved it did not match the bullet that killed Hodson.

The path of the bullet was also an issue. It had entered on the right side between the ribs, passing through and coming out Hodson’s left side one inch lower. The defence called an expert witness, mathematician Terry Speed, who had plotted the trajectory of the bullet using the exit and entry points. He calculated that the bullet could only have come from the No. 2 watchtower, where Warder Bennett was standing and aiming his rifle, much further than from where Ryan was. Opas said Ryan would have had to be more than eight feet tall to fire on that trajectory.

But the prosecution pointed out that this assumed Hodson was standing upright. If he was crouching down as he attempted to grab Walker, then the bullet could have come from Ryan’s carbine. A number of witnesses testified that Hodson was standing upright, but others said he was bending down.

Another point in Ryan’s favour was that a warder testified that Ryan was to the left of Hodson at the moment he was shot. This would have made it impossible for him to have fired the shot, which entered Hodson’s body from right to left.

If Ryan had been standing, the shot could have come either from Bennett in the tower or from Paterson near the garden wall, Opas argued. Paterson would only have to miss Ryan by about half a degree to have hit Hodson ‘in the very way that in fact he was struck’.

This theory was even stronger given that most witnesses, except Paterson, said they only heard one shot.

The defence also made much of the number of shots in the carbine’s magazine. Opas argued there were eight shots in the magazine when Ryan grabbed it, and all but one were accounted for. That one bullet was ejected before Hodson was shot, he claimed. When Ryan grabbed the carbine and cocked it, a round was ejected because the safety catch was on. Warder Lange and ballistics experts confirmed this during the trial.

Unfortunately for Ryan, that shell was never found either. Opas said that someone had probably picked it up while cleaning. If this was true, Ryan could not have fired a shot.

Opas decided to put Ryan in the stand and cross-examine him directly about the shooting. Fearing Ryan’s reputation for escape, 15 police and warders stood shoulder to shoulder, blocking the two ground-floor exit doors, as he walked from the dock to the stand.

Ryan took the oath, and Opas asked him, ‘Did you murder prison officer George Hodson?’

‘No, very emphatically not,’ Ryan said.

‘Did you fire a shot?’ Opas asked.

‘I did not discharge the gun. I have never fired that gun,’ Ryan replied firmly.

In his closing summary, Opas argued that there was too much doubt to convict Ryan. The mathematical evidence about the trajectory of the bullet was indisputable, and there was a distinct possibility that another warder could have killed Hodson.

‘I suggest you could not go home and sleep soundly in your beds if you returned a verdict of guilty against this man on the evidence you have heard in this court,’ Opas said.

But the prosecutor, Solicitor-general Basil Murray, said the evidence was overwhelming. No fewer than eleven people had seen Ryan fire the fatal shot, and three policemen had testified that Ryan verbally confessed to them the day after his arrest in Sydney.

‘Why on earth would they want to invent such a lie?’ Mr Murray asked the jury. To do that would be perjury, a serious offence.

Fifteen days after the trial began, the jury retired. They deliberated for seven and half hours. Despite the very convincing evidence of the bullet’s trajectory and doubts about whether Ryan’s gun had ever been fired, they found Ryan guilty. Walker was found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter and sentenced to twelve years.

On being asked by Justice Starke if he had anything to say as to why the death penalty should not be passed, Ryan replied, ‘I still maintain my innocence and will consult my counsel with a view to appeal.’

A few months later, Walker himself escaped the death penalty. At his trial for the murder of Arthur Henderson, he persuaded the jury that he had killed Henderson in self-defence. He was found guilty of manslaughter rather than murder, and was sentenced to another twelve years in jail.

Ryan’s lengthy period of appeals was accompanied by public protest and debate that would plunge Bolte’s government into crisis. Opas first appeared before the Victorian Full Court in May to request a retrial on the grounds that the judge had misdirected the jury when he said it was not open to them to reach a verdict of manslaughter.

The appeal became bogged down in a somewhat technical argument over whether Walker and Ryan were still in the act of escaping when Hodson was shot. Opas argued that the felony of escaping had finished once the two were outside the prison walls, so the felony murder rule did not apply, and the jury should have been instructed that it was possible to find Ryan guilty of manslaughter.

The court, however, took the view that the rule applied during the whole escape period of nineteen days. The appeal was lost; in October, Ryan was refused leave to appeal to the High Court, though the judges’ decision was not unanimous.

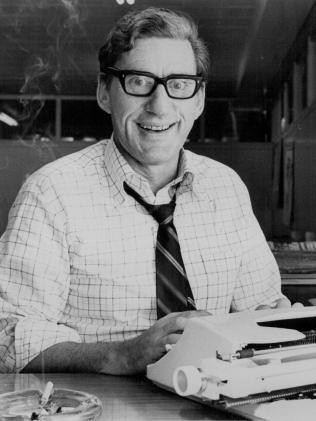

While the appeals went on, some of the most influential people in the country cranked up a campaign to get Ryan’s sentence commuted. The leader of the campaign was Barry Jones, secretary of the Victorian Anti-Hanging Committee.

Jones, a former teacher and future federal government minister, who had a strong public profile as a popular TV quiz-show contestant, abhorred capital punishment and had been heavily involved in the anti-hanging movement in Australia for some years. He secured support from other influential figures and mobilised public opinion against hanging in general and for Ryan in particular.

Even members of the jury who had convicted Ryan were not happy. One of the jurors came out publicly and said he believed that when he was making his decision about Ryan’s guilt, he mistakenly believed that capital punishment had been abolished in Victoria. He did not realise their decision would mean Ryan would hang. Four other jurors thought the same thing, he said.

Five of the jurors petitioned the government to commute Ryan’s sentence. If they had known hanging was a possibility, they said, they would have made a recommendation for mercy. The decision to hang Ryan was also opposed by just about every media outlet, church and welfare group, but Bolte refused to give in. On 12 December, Bolte and his Cabinet decided Ryan’s death penalty would stand and set 9 January 1967 as the date for his execution.

Opas played his last card — an appeal to the Privy Council in London. Bolte refused financial support for the appeal, but Opas agreed to take it on a voluntary basis. The Bolte government now had to postpone the execution to allow the appeal to be heard. Opas flew to London, where he put the same argument forward about the felony murder rule. But he was not optimistic, he told Ryan before he flew out, because the Privy Council rarely intervened in criminal matters.

Ryan shrugged and said, ‘We’ve all got to go some time, but I don’t want to go this way for something I didn’t do.’

Then he smiled and added: ‘You know, mate, we’re playing time on. If you don’t kick a goal soon, we’re going to lose this match.’

They shook hands. It was the last time Opas saw him.

As predicted, his appeal to the Privy Council was turned down. On 24 January, Cabinet met again and set a new date for Ryan’s hanging. The new date was 31 January.

But it was not over yet. On the night before Ryan was due to hang, sensational new evidence surfaced. A Pentridge prisoner called John Tolmie had come forward and said he had seen a warder in Tower 2 fire his gun on the day of the escape. Ryan’s solicitors won a stay of execution while Tolmie’s claims were investigated. But it didn’t take long to find out that he was lying; he wasn’t even in Pentridge on that day. Tolmie admitted he had concocted the story in an attempt to delay the execution, hoping something else would come up.

On 1 February, another former prisoner, Allan Cane, made a statement claiming he had seen a warder fire a shot from Tower 1 during Ryan’s escape. Cabinet considered the statement, but it did not change their minds. Cane even flew to Melbourne from Brisbane the night before the hanging and tried to get a meeting with the state attorney-general, Arthur Rylah, but it was no use. Rylah refused to see him. Ryan’s fate was set.

Ryan had told his friend and confidant Father John Brosnan, the prison chaplain, that he was now resigned to die.

Bolte didn’t even wait for the Queen’s official rubber stamp on the Privy Council’s decision. Ryan was hanged a week before the Government Gazette officially announced the appeal had been dismissed. As Jones summed it up, ‘I doubt if Ryan had an intention to kill, but I am certain that Bolte did.’

At the appointed hour, Jones had stood with a crowd in silent protest under the clocks at Flinders Street Station. Afterwards, he went home and lay on his bed for the whole day staring at the ceiling. He was haunted by the question of whether had he done enough. Had he been smart enough strategically? The issue was so painful that he could not speak publicly about the hanging and refused all interviews on the subject until 2002.

Even in 1975, now a state MP, when he addressed the Victorian parliament on the occasion of the bill that would abolish capital punishment, he mentioned Ryan’s name only twice in passing. He said Ryan’s hanging left him with a scar in his mind that would never heal.

*

The case of Ronald Ryan has never really been closed. New allegations and theories have continued to emerge. A few years after the hanging, a man with a thick accent rang Mr Opas saying he was a friend of Helmut Lange, who drank with him at the Austrian Club in Fitzroy.

The man said Lange had confirmed to him that Ryan had worked the bolt on the carbine as soon as he took it from the rack on the tower that day, and that bullets were ejected onto the floor because the safety catch was on. This was the evidence that supported Ryan’s claim he had not fired a bullet from the carbine because all eight bullets in the magazine were then accounted for.

The man also told Opas that Lange had picked up the bullets and put the incident in his written report, but two weeks later, prison officials told him to rewrite the report, leaving out the incident with the ejected bullets. They had threatened that if he didn’t, he would be charged with helping Ryan escape and lose his job.

The theory couldn’t be tested, because by now Helmut Lange was dead. He had committed suicide while on duty at Pentridge on 12 April 1969. Opas claimed Lange had been worried about the false report he had written. When he was recommended for a commendation for bravery for his actions during the escape, he refused to attend the ceremony at Government House. He believed the medal was a reward for giving false evidence, Opas argued.

Then, in 1986, another former warder, Doug Pascoe, claimed in a television interview that he had fired a shot during Ryan’s escape bid. Pascoe said he was in Tower 3 that afternoon and fired a shot at Ryan. He admitted he did not have a clear shot; it was a ‘stupid and irresponsible’ action, and he could easily have hit Hodson instead. He said he did not own up to firing at the time because no-one asked and he was too scared to tell anyone.

But Pascoe’s claim was immediately dismissed by the police and the prison governor at the time, Ian Grindlay. Grindlay said Pascoe could not have hit Hodson, even by accident, because the distance between the two was well beyond the carbine’s range. The police said Pascoe was rostered on Tower 4, which was even further away, making it more unlikely he fired the fatal shot.

Then in 1993, a former Pentridge prisoner, Harold Sheehan, claimed he had seen a warder fire a shot from a tower, as Ryan’s defence team had suggested. Sheehan had been walking past Pentridge at the time. He also said he saw Ryan down on one knee when he had his rifle aimed at Hodson. If that was the case, it was even more unlikely he could have shot the warder, given the trajectory of the bullet.

‘There is no way in the world that Ryan’s bullet was the fatal one,’ Sheehan said.

Again, the police and Grindlay dismissed the claims.

There were two schools of thought among those who supported Ryan — those who opposed the death penalty regardless of his guilt or innocence, and those who believed fervently that Ryan was innocent.

Philip Opas was chief among those who believed Ryan did not do it.

He continued to argue Ryan’s innocence right up to his death in 2008. He suggested that if Ryan had been guilty, he would have told him or Father Brosnan at some stage. Brosnan said Ryan had never admitted his guilt to him. Publicly, Ryan insisted on his innocence right to the end, but some claimed he had admitted guilt in private conversations.

One who did believe him guilty was, surprisingly, Brian Bourke, Opas’s junior at the trial. He said in an ABC interview in 2005 that, while he was against Ryan being hanged, he did not have much doubt about his guilt.

‘One of the problems of the trial, of course, was an alleged admission that he made on the plane back to the homicide fellows. Those sort of things can’t happen now, because they’ve got to be recorded on tape, but whether he made the admission or was verballed, I don’t know. He was a pretty talkative fellow — he might have,’ Bourke said.

The issue for Bourke was not Ryan’s innocence but capital punishment itself. He said, ‘That’s what Barry Jones and everybody was on about: the death penalty. I mean, if Ronny hadn’t been hanged, well, this trial would have just been in oblivion now — no-one would have known anything about it. But I didn’t have much doubt about his guilt.’

Pentridge’s governor, Ian Grindlay, said Ryan had told him ‘straight out’ that he had shot Hodson but had not meant to kill him.

‘Ryan himself told me he shot Hodson,’ Grindlay told The Sun newspaper in 1986. ‘He was an experienced kangaroo shooter. He said he aimed at Hodson’s shoulder to slow him down so that Walker could escape.’

Grindlay saw it as ironic that Ryan should have killed the warder. ‘Ryan liked Hodson,’ he said. ‘It was an accident, just bad luck that the bullet deflected down to hit the heart.’

Grindlay’s claim is supported by journalist Evan Whitton, who worked for Melbourne’s Truth newspaper at the time and witnessed Ryan’s hanging. Whitton was told by a very reliable source in Pentridge that Ryan sent a message to Walker in those last days. It read:

I am being executed for you. I could have got away and left you to Hodson. To get you away I had to shoot Hodson. I did it for friendship. Good luck to you.

Whitton also said Ryan wrote a letter on some toilet paper to his wife and children while awaiting his execution. Whitton’s source, a warder, gave him the letter and asked him to pass on copies of it to his family, which he did.

Whitton said, ‘Ryan had previously written letters to Truth. Ryan’s warder apparently treated him as a human being, and Ryan apparently trusted him to get the letter to Truth for transmission to his wife.’

In the letter, Ryan wrote, ‘With regard to my guilt I say only that I am innocent of intent, and have a clear conscience in the matter.’ This suggests he did shoot Hodson, but his death was an accident.

If so, why didn’t Ryan admit it, instead of claiming he never fired a shot? Perhaps he thought a jury would never believe the shooting was an accident and that he was guilty only of manslaughter. Better to deny it altogether and let Opas defend him using the trajectory evidence and the argument it was a warder who shot Hodson.

*

To understand Bolte’s steely determination to hang Ryan in the face of massive public opposition, you need to go back to 1961, when a man called Robert Tait brutally murdered an elderly woman in a Hawthorn vicarage. Tait was found guilty of the bashing murder of Ada Hall, the vicar’s mother, and sentenced to hang. For Bolte, this was one of the worst type of murders, and he was determined the sentence would be carried out.

But Tait’s legal team, after exhausting all avenues of appeal, eventually succeeded in having Tait classified as insane at the time of the murder, forcing Bolte’s government to commute the sentence at the eleventh hour.

Bolte did not believe the insanity plea for a minute and was furious that he had been outwitted by the medical and legal fraternity. He vowed he would never suffer the humiliation of such a situation again. And so it was that Bolte got the hanging he desperately wanted with Ryan. It must have given him extra pleasure to have the sentence pronounced by Justice Starke, who in his earlier role as a barrister had frustrated Bolte’s intention to hang Tait.

Despite his defiance, Bolte was also defensive. In later years, when he reflected on his decision, there was touch of the Nuremberg defence of ‘I was only following orders.’

‘Do not think I derive any pleasure out of the decision to hang Ryan,’ Bolte said. ‘It never occurred to me that I had the power of life and death. No bloody fear: it was the law said Ryan should hang, not me.’

Bolte also claimed it was the will of the Cabinet. ‘In Cabinet’s opinion it was a clear-cut case. Ryan killed a warder who was doing his duty, trying to prevent a jail escape … For that Ryan deserved to die, and I’ll believe that until the day I die.’

He even tried to lay the blame at the feet of the media, which overwhelmingly opposed the government’s decision. He said, ‘Let’s get one thing straight: the media hanged Ryan, not me. It had reached the stage where the Victorian government would have been discredited if it had backed down and given Ryan the reprieve the media demanded … not asked, demanded!’

It says a great deal about the man that he was willing to pay for his government’s credibility with another man’s life. Bolte’s determination seems formed more out of petulance than principle.

In the end, Bolte’s controversial decision did not harm him politically. He was re-elected decisively in the state election in April 1967 and remained premier until 1972.

But the death penalty itself was finished. Not even a conservative government would dare to sanction a hanging after the Ryan furore. Ironically, it was Bolte’s successor, Rupert Hamer, who led a small-l liberal government to abolish the death penalty in Victoria in 1975.

It was another ten years before the death penalty was finally eliminated throughout Australia. In 1985, New South Wales became the last state to abolish it for the crimes of treason and piracy.

*

While the case of Ronald Ryan brought the issue of hanging to a close, the first steps on the path to end capital punishment were taken early in the nineteenth century. The Australian colonies followed the example of England in lifting the death penalty for minor crimes. From 1833, cattle stealing and forgery were no longer hanging offences in Australia, and in 1838 nonviolent burglary, rioting and smuggling were also struck off the list.

The next step was the abolition of public executions. Here, several of the Australian colonies took action before Britain. In the early years of European settlement, hangings could be — and often were — held in public venues, presumably in the hope of enhancing the deterrent effect. Those who witnessed the gruesome finality of hanging, its advocates claimed, might be more inclined to fear it.

In reality, public executions might have satisfied observers’ morbid curiosity, but they did nothing to prevent crime. In 1853, Victoria, Tasmania and New South Wales took the view that the practice was abhorrent and brutalised those who witnessed it. All three colonies banned public executions.

Over the century that followed, there was growing antipathy to capital punishment. Moving the execution away from the public gaze was not enough to satisfy the anti-hanging movement, which was inspired by similar campaigns in Britain. Prominent church figures in both countries argued that the practice was inhumane, un-Christian and ineffective as a deterrent.

One of the early indications that public opinion against the death penalty was growing came in Bendigo in 1873, when a man named Samuel Wright was hanged for attempted murder. Wright was a nasty piece of work, a habitual criminal with violent tendencies. Aged over 60, he had been living in a decrepit hut on the outskirts of Bendigo with a 17-year-old girl, whom he had got pregnant. Desperately unhappy with her relationship, the girl left Wright and sought shelter with a couple she knew. Wright tracked her down, they argued, and Wright threatened her with a pick. When another man, Arthur Hagan, tried to intervene, Wright turned on him in a rage and drove the pick into his head.

Hagan survived, but was left with permanent injuries. While no murder was committed and there was no evidence of premeditation, Wright was sentenced to death.

The judge, Justice Fellows, had no qualms about the sentence, arguing that the assault was one of the worst he had seen. The jury felt otherwise and publicly called on the government to show mercy, but the executive council confirmed that Wright would hang.

The editor of the Bendigo Advertiser was not impressed with Justice Fellows’ decisions in general and objected to this one in particular. Fellows had only just been appointed to the bench, and this was his first visit to Bendigo. One wonders if his enthusiasm to notch his belt with a hanging had got the better of him.

On 13 March, two days after Wright’s hanging, the paper attacked the decision in an editorial. It argued that there should have been clemency in the absence of premeditation and pointed out that others found guilty of similar crimes had received far lighter sentences. ‘If the punishment was a just one,’ the editor wrote, ‘very great judicial errors have been made in the past’. The newspaper called for immediate reform to achieve more consistency in administering the law.

It was becoming accepted that issues such as provocation, premeditation and insanity should be taken into account before the death penalty was imposed. There was particular concern at the sheer finality of the punishment, especially when verdicts were reached on questionable evidence.

By the late nineteenth century, these doubts were being widely aired. In 1889, for example, the Burra Record in South Australia ran a long editorial on the futility of capital punishment after a man called William Harrison was hanged for murder. The police evidence against Harrison was circumstantial; it was mainly based on the fact that similar crimes involving robbery and murder had taken place in various places when he was there. These included the Deniliquin murder for which Joseph Cordini had been hanged. The first time he was tried, the jury could not agree on a verdict. But he was tried again, found guilty and sentenced to death. Harrison went to the gallows protesting his innocence — and that of Cordini as well.

The newspaper editorial highlighted one extremely good reason for opposing the death penalty — that innocent people might be hanged, and there was no way back. It said, ‘Many victims of the law, who have afterwards been proved to be innocent, have passed to their doom; they have died by the hand of the common hangman and the law was their murderer, and the guilt of the crimes lies on the public conscience.’ It described capital punishment as a ‘relic of savagery’ and ‘absolutely worthless as a deterrent to crime’. ‘We would ask, why should the country risk the terrible responsibility of committing murder when there is nothing gained by it?’ the editorial thundered.

The Labor Party adopted an anti-hanging platform almost as soon as it was formed in the 1890s. In his book on capital punishment, Barry Jones argued that this was an emotional conviction rather than a decision based on the evidence that hanging did not deter crime. He wrote, ‘The main factor was probably the view that judges, lawyers and the state ought not to be able to hold the power of life and death over victims of society — even criminal victims.’

With the Labor Party leading the push for reform, Queensland struck off two more capital crimes in 1899: wounding while committing a robbery under arms would no longer be a hanging offence, and neither would rape. Reformers argued that the law on robbery under arms was outmoded, designed in the days of bushrangers. Hanging someone for rape was regarded as too harsh a penalty, and reformers argued it might even encourage rapists to murder their victims as a way of getting rid of the primary witness to the crime.

State governments ultimately held the power to hang. Judges had no discretion; the death sentence was mandatory for convicted murderers. Some in the anti-hanging movement believed that this encouraged juries to acquit, not because they believed the accused to be innocent but because they did not believe the crime warranted the death sentence. They did not want a hanging on their conscience.

The governments of the colonies — later, the states — had sole power to commute a death sentence. They became increasingly ready to use these powers, particularly when Labor was in government. Hanging became a political football. Labor opposed it and would commute death sentences when it could. Conservative governments supported it, though they did increasingly commute death sentences as the twentieth century progressed and public opposition grew.

But conservatives continued to resist Labor’s efforts to have the death sentence abolished altogether. They believed in its deterrent value, despite evidence to the contrary. Though they increasingly limited it to the most gruesome murders, they believed government should have the choice to use it or not.

Then, in 1922, Labor finally had a victory when Queensland became the first state to abolish the death sentence for all crimes. It was a close-run decision, though, with the Theodore Labor government only narrowly winning the vote in parliament, faced with bitter opposition to it in the community.

But the Queensland decision helped to settle the argument about whether hanging was effective as a deterrent. The murder rate in Queensland did go up somewhat for several years after 1922, but from 1929 it dropped, falling to its lowest level since 1900 and remaining low for the next three decades. Anti-hanging campaigners cited this as proof that abolition did not lead to more murders.

This is not to say that there was widespread support for abolishing capital punishment elsewhere. State Labor governments tried to follow Queensland’s lead for decades, but were beaten each time. Without the death penalty as the ultimate sanction, conservatives feared that society would somehow descend into chaos.

The strongest argument, though, for the abolition of the death penalty was surely the possibility that it could be inflicted on someone who was later found to be innocent. There are doubts about guilt in many of the cases we have seen here. There have been miscarriages of justice through inadequate or prejudiced evidence, rushed trials and insufficient resources; many of these cases today may well have been thrown out of court.

No case exemplifies the fallibility of the death penalty better than that of Colin Ross, who was hanged in 1922 after he was found guilty of strangling a young girl outside his wine saloon in Melbourne. The primary evidence against him was that the girl’s hairs had been found on blankets in the saloon. It was not until 1998 that the evidence was finally re-examined using modern forensic technology and DNA testing. A researcher called Kevin Morgan, who had been investigating the case, uncovered the original file of evidence, including the hairs. Tests proved unequivocally that they did not belong to the murdered girl. Ross had been wrongly convicted. He received a posthumous pardon in 2008; it was the first case of a wrongful hanging proved in Australia.

Even after all the states had abolished capital punishment, one final step was needed to avert the possibility that a state could reintroduce it in the wake of a particularly heinous crime. There might also be electoral attractions. While support for the death penalty has declined over the past twenty years or so, it still remains at a fairly high level. According to an Australian National University study, 45 per cent of Australians support the reintroduction of the death penalty for murder.

In 2010, the federal government introduced legislation to eliminate that possibility by removing the states’ powers to pass a capital punishment law. The measure does not preclude a federal government in the future rescinding the law — only a change to the constitution could do that — but at least the states who wielded this power for most of our history can no longer do so.

In the Victorian parliamentary debate on abolishing the death penalty in 1975, Barry Jones made one of the most heartfelt and passionate speeches of his career. He said the bill was more than just a vote to abolish a regressive and brutal law. It was a vote ‘against darkness, against obscurantism, against instinct, against pessimism about society and about man’s capacity for moral regeneration’.

With the passage of the 2010 federal law, that darkness has been cleansed from the nation’s soul. No longer can Australian society make one of its own pay for a crime with their life. No more can our collective conscience be tainted with the guilt imposed by this ‘relic of savagery’. For the first time since Thomas Barrett swung from a tree at Sydney Cove, we are truly free of one of the worst burdens of our history.

- This is an extract from Noose: True Stories of Australians who Died at the Gallows by Xavier Duff, published by The Five Mile Press Pty Ltd, RRP $32.95. ©Xavier Duff 2014

- This is an edited version of a story first published in May 2014

Originally published as From petty crim to jailbreak killer: The story of Ronald Ryan, Australia's last man hanged