Part 2: 96 seconds that saw the Australian criminal underworld implode under Operation Ironside

PART 2: This is the moment Australian Federal Police created the AN0M app — a Trojan horse that could expose criminals and their networks.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

PART 2: This is the moment Australian Federal Police created the AN0M app — a Trojan horse that could expose criminals and their networks.

96 SECONDS THAT SMASHED THE UNDERWORLD

The Operative was sitting on the couch in the loungeroom of his Canberra home, doing what he did most nights – working on AN0M.

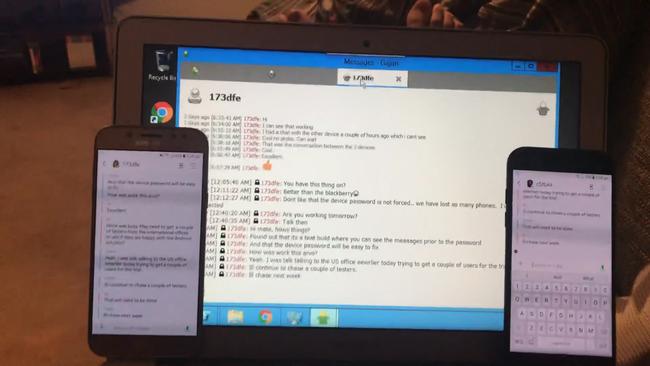

He had two mobile phones and a laptop propped up on his knees and he was sending encrypted messages backwards and forwards between the two phones via the app.

Then, on the laptop in front of him, appeared the words of the messages he’d been sending himself.

The Operative dryly recalls that “one of the most exciting times for me was when we proved the concept that we could collect encrypted messages and decrypt them from the platform’’.

“Phone here, phone there, my laptop here. I sent a message to that phone and I could see the encrypted messages come up on the computer,’’ he said.

He videoed the moment with yet another phone, showing the messages pinging backwards and forwards between the two phones and scrolling down, unencrypted, on the laptop.

The Operative sent it off to all his colleagues.

The 96-second clip, which would later be shown to the AFP top brass, inadvertently also captured The Operative’s bare feet.

“I had to sell this to the executive – like, this is possible, we can do this,’’ The Operative says, defending his feet cameo on the basis “it was like 10pm at night’’.

His colleagues were thrilled with the development – and grateful that at least he had his pants on.

“And he sent us the video and it’s like, ‘yeah, we like your bare feet, it’s a nice touch’,’’ Nelson says.

To an untrained eye, it’s hard to square off how the decryption works – the video shows some of the messages are identical on each phone, but other words on the laptop screen.

But The Operative and The Investigator knew what they’d done, as did Nelson.

Access, decrypt, and collect.

Despite his technical wizardry, The Operative is not a formally trained computer engineer.

“My whole law enforcement agency career has been around legally accessing criminal communications. I would not call myself a tech compared to the people I work with in Digital Surveillance, but … to the operational members of the AFP, I am a tech,’’ he says.

However, he worked closely with the tech experts and specialists within in the AFP’s digital surveillance collection unit on the plan.

“The real magic of Ironside was the work that three members from the Digital Surveillance Collection area did in rebuilding a server that collected and decrypted the communications,’’ The Operative says.

The Investigator too was no tech expert, with “nil qualifications’’ in technical design but decades of experience investigating organised crime, and working out how the criminal networks operated.

“I relied heavily on The Operative and Rob Nelson and the wider Digital Surveillance Collection (unit) – they are the experts. In fact they are world leaders,’’ he said.

“There is no one on this planet with the expertise and knowledge that The Operative has. His technical expertise, especially in how these devices operated and the market they operated within, coupled with his experience working in and understanding of the organised crime environment, placed him in a unique and highly specialised position. Without him we wouldn’t have got to first base.’’

The plan came off because of a group of like-minded and passionate people from the FBI and AFP worked together and stuck at it, The Operative says.

“We each took a little bit of the problem away and worked on whether the idea could work. There was a technical piece: Accessing and decoding the messages. There was a legal piece, and a management piece.

“The AFP took responsibility for the technical piece, the FBI took the management piece and both agencies worked on the legal piece.”

In the early days, Nelson, The Investigator and The Operative mostly worked the operation alone, often at night and after hours, backed up by the AFP’s tech and digital experts.

They had to convince the AFP hierarchy that it would work, that they could manage the volume of messages that would come in if it was successful, and that they’d be able to pick up any immediate threats to life caught in the communications.

They also had to make sure the platform couldn’t be hacked by commercial competitors and looked authentic enough to trick criminals into embracing it.

And they had to work out how to get it into their hands.

Gaughan signed the Major Controlled Operation authorisation on September 25, 2018, which lay the groundwork for police to covertly infiltrate crime networks.

He remained anxious about the potential for a threat to life to be made on a device, but be buried under the mountain of messages, and not picked up by police until it was too late.

That was his “red line”.

“Ultimately, if someone got killed and we had a device and we later found out, I would have pulled the plug on it,’’ he recalls.

“A red line for me would have been, ‘Boss, we’ve found this text message, it relates to this hit that’s occurred in blah, we missed it’. I would have said, ‘we’re done’, because that’s just too high risk.

But for now, it was all systems go.

The AFP’s National Operations State Service Centre generated a list of possible names for the operation.

One was Operation Ironside.

The Investigator grabbed it, seeing the linkage to the Viking Bjorn Ironside.

“The Vikings were determined and ruthless in fighting whatever they went up against,’’ he says.

They had the approvals. Now they had to make it work.

HUNTERS AND COLLECTORS

To catch crooks, the Ironside team had to think like crooks – but act like a dotcom start-up.

Police couldn’t just start planting devices fitted with AN0M and expect an immediate front pocket ride with the underworld.

New and some struggling platforms were emerging after Phantom Secure offering better devices with better encryption and privacy features, including EncroChat out of Europe, and Sky ECC, out of North America.

To win customers, AN0M had to be a cutting-edge product that offered users everything they wanted in a device and more.

But to make sure nobody ended up dead, it had to be able to read its customers minds and interpret whether their messages were harmless or heinous.

The handsets were a mobile phone stripped of its normal functions. They could not send emails, make calls, find maps or do Google searches.

The app was pre-loaded and hidden behind a seemingly-innocent calculator icon.

Once the user typed a secret access code into the calculator, the app would open.

As well as end-to-end encryption of messages, it distorted voice messages as a further layer of anonymity.

One of AN0M’s special features was a remote access kill switch – a promise that all data would be remotely wiped if police got hold of one of the devices and cracked into the app.

Subscribers paid a monthly fee for the privilege of a remote wipe, with no idea their cash was going straight back into the FBI’s pockets

Handset and subscription packages each cost between $1500 and $2500.

It is not illegal to have encrypted apps on your phone.

Millions of law-abiding Aussies use mainstream apps such as WhatsApp or Signal every day.

But those Aussies usually have a mainstream telco provider and provide identification to purchase their handsets and phone plans.

AN0M buyers and those using other shady encrypted platforms through custom-stripped handsets did not provide identification, operated only under false names or handles, often used SIM cards routed through other countries, and generally tried to remain anonymous.

That is where resellers – grey marketeers hiding behind flashy aliases who were the same people who had been selling Phantom Secure handsets – came in.

Police wanted the device to appear completely authentic, so they plugged into the reseller market, which they already knew from criminal investigations.

“Criminals generally purchased the encrypted device from underground resellers … They would usually have to know someone that was already using a device to place an order,’’ The Operative says.

Once one crook in a network had a device, he would often order more for his associates so they could communicate.

Sometimes devices were paid for in cash while other preferred to pay in cryptocurrency, mainly Bitcoin.

The app would be activated, usually by the reseller, after access codes requested from the AN0M administrators, were entered.

If The Operative and his offsiders had ventured into the private sector, they could have made a fortune in Silicon Valley.

But bringing down organised crime meant far more to them than making a motza for someone else’s start-up.

“If you talk to the guys, they’re all invested in the actual mission,’’ the AFP’s Commander of Covert and Technical Operations, Doug Boudry says.

“In private industry they would be earning someone else a lot of money – here in the AFP what they’re doing is actually having a tangible effect. Not only for themselves but for their families and the community.

“The other things is they’re hunters by nature. They like going after the bad guys. There is something fun in that. There is a sense of belonging to something when you’re going after the criminals.’’

Do you know more? Email us at crimeinvestigations@news.com.au