Four towns where our famous Australians come from

From small towns and wave beaches to public schools and surf clubs, these are the huge Aussie success stories to emerge out of the country’s lesser known destinations. See the exclusive video.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Comedian Wendy Harmer, as a cadet journalist at the Geelong Advertiser, would type and retype until she was delirious.

Harmer thrilled to the adrenaline of deadlines, if not to the male chauvinism, of the 1970s era.

Each shift, from 4pm to midnight, she tore around the town on her powder blue pushbike, whizzing past the woolsheds and warehouses on the seafront.

She’d check in at the police headquarters on Gheringhap St. She’d pick up the weather map from the last Melbourne train of the night.

Harmer learned to write, to edit, and to thrust herself into the slipstreams of comedy and the stage. She reflects on Geelong with gratitude and fondness.

“It was a country town with big ideas,” she says. “It was almost a country town that was too big for its boots.”

Watch our exclusive video above where we interview some of Australia’s famous faces about where they were born.

News Corp research suggests that Harmer is right.

An exclusive database of thousands of notable and successful Australians shows that some regional centres of Australia, such as Geelong, Victoria, outshine their capital city counterparts in per capita measures of fame, talent, power and innovation.

Geelong produces sportspeople, actors and the odd comedian.

So does Newcastle in NSW, which features a single high school alumni of rock stars, surfers and artists.

In Queensland there’s the Gold Coast, that holiday mecca for the cooler states, which throws up back stories in ripped muscle and resilience, the starting blocks for so many Olympic medals.

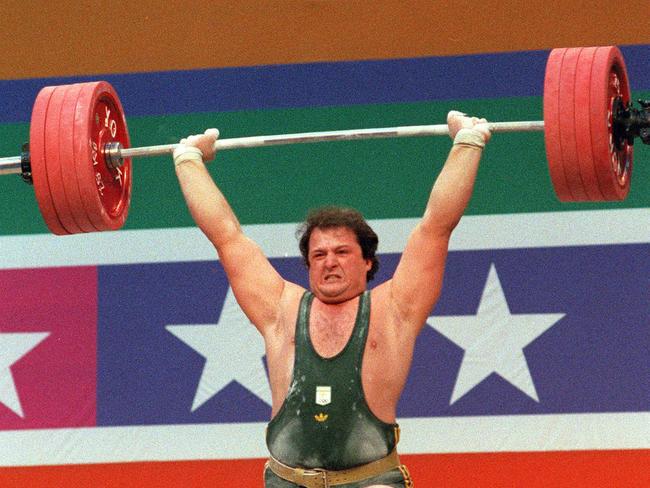

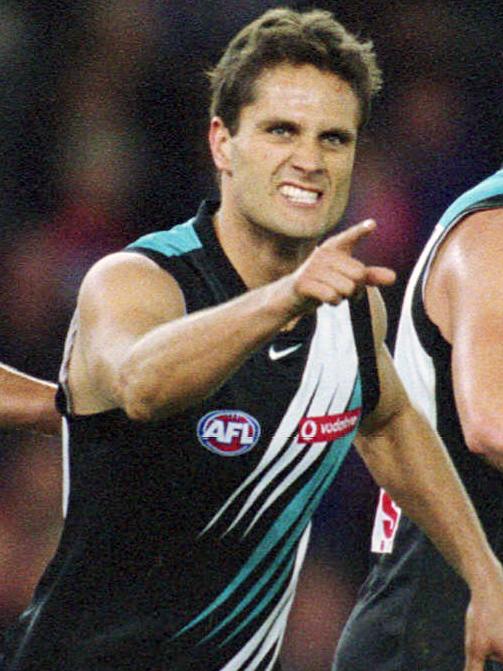

In South Australia, almost four in five people live in Adelaide. Yet Mount Gambier (pop 27,846), was the birthplace of musicians Kasey Chambers and Dave Graney, as well as the AFL football’s Gavin Wanganeen. Port Lincoln (pop 17,009) gave us Olympians Dean Lukin and Kyle Chalmers.

While Harmer trundled around Geelong town, ferreting out stories, Ian Cover was back in the office, probably being berated by one of the newspaper’s male mandarins for an alleged crime against punctuation.

Cover remembers the time, late at night in the office, when Wendy Harmer swore him to secrecy. She was photocopying articles for a tilt at a bigger job, a storeyed journey which led to a national perch as a TV comedian, radio host and last year’s autobiography, Lies My Mirror Told Me.

The younger cadet journalist, who would go on to spend 43 years on radio as a Coodabeen Champion, was fresh out of Belmont High School, a renowned factory line of mega talents.

There, Cover remembers Chrissy Amphlett, a star sprinter, who would grow up to be the sultry diva of the Divinyls.

He recalls international baritone Peter Coleman-Wright and international soprano Cheryl Barker, who played opposite one another in the school production The Boyfriend, and have now been married for more than 40 years.

Geelong is like that. Footy. Business. The arts. Around here, everyone knows someone who knows someone.

Debbie Fraser also knew Amphlett – Fraser, at 10, played her younger sister in a local production of Annie Get Your Gun.

She came to know Coleman-Wright, and his “amazing voice”, when he spent six years with the Geelong Society of Operatic and Dramatic Arts Junior Players.

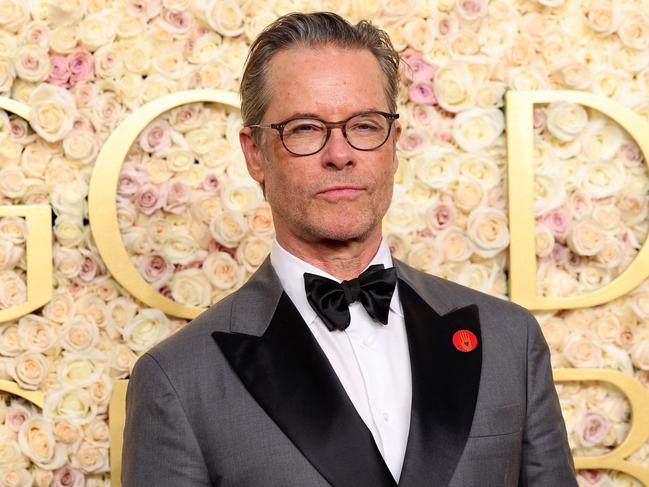

Fraser also, as the troupe’s director the half century or more since, directed a teenage Guy Pearce.

Back then, the Oscar tip was “just Guy”. He was a handy footballer who could sing, but not dance so well at first.

A week before a 1984 production of Queen of Hearts, Pearce did his knee playing footy.

“Oh no,” said the director. “I can do it, I can do it,” replied Pearce, who would limp through the performance in a knee brace.

Another Geelong talent pool which keeps giving is St Joseph’s College on the other side of Latrobe Terrace in Geelong’s Newtown.

More than 50 ex-students have played AFL footy, including premiership captain, Cameron Ling who cannot quite explain the school’s overrepresentation at the elite level.

“I think Geelong is lucky,” he says. “Like a lot of bigger country towns, there’s plenty of space, the outdoor lifestyle, the beaches at your doorstep.”

Football fortunes drive the mood of the city – Monday sickie rates rise, or so the story goes, when Geelong loses its weekend AFL match.

Ling, a benchmark in humility and red hair, was the premiership player when a 44-year drought was broken in 2007.

A bloke gawked when Ling walked into a surf beach café not long after the flag win. “My life is complete now,” the man told Ling. “I’m happy.”

“There are lots of more important things in life,” Ling says of football in Geelong, “but sometimes it doesn’t feel like it.”

Pearce returns to Geelong for Junior Players reunions.

At the 50th birthday, about 340 people attended. Pearce complied with about 340 selfie requests.

“It’s the unique connection that you have that you keep,” Fraser says in explanation.

Search the database to see where Australians were born below. Best experience for Android users will be on web.

Olympic gold medallist Sally Pearson knew at six-years-old that she wouldn’t conquer the gymnastics world. But she felt, almost knew, that she could be the best at something.

Her mum signed her up to little aths after they moved to the Gold Coast, from Sydney.

Pearson had no interest in or understanding of running races at that point.

She duly won her first race. Without the flips and tumbles of gymnastics, Pearson found it “kind of boring”.

There were other downsides, such as the “terrifying” swirl of bats at the Helensvale track on the Gold Coast every Friday night.

But her path was set, perhaps from that moment of walking down the plane stairs into a “hot blanket of wet”.

There was the unwavering dedication to her hurdling talent, the stony-faced preparation which dissolved into unchecked joy in the post-race interviews.

Yet Pearson says it was the adventures she led outside of athletics, as she rose from state to national status, that scaffolded her formative years.

“They built the AIS in Canberra because it wasn’t distracting to athletes outside of their training,” she says. “Then I think they realised that athletes’ livelihoods outside of their sport is so important for their happiness.”

The Gold Coast has produced a ridiculous number of national sporting heroes. Hopefuls land here, to join the bustle of the 6am throngs of runners, swimmers and surfers at the endless stretches of beach.

Their training is paramount, obviously. But the time-outs matter. Bond University’s head swimming coach Chris Mooney calls it “life medicine”.

“Swimming is what we do, it’s not who we are,” he says of a squad which includes Flynn Southam and Milla Jansen. “Who we are needs to be quite holistic people with good values - and distraction.”

Ky Hurst, the former ironman, Olympian and professional sailor, agrees.

He came home to Queensland, to the Gold Coast, to live in his teens. Tugun Surf Club, in the south, would be his ground zero.

He was 16, competing against adult men.

“They were certainly idols, but at the same time I kind of knew that once I got a bit of experience under my belt, I knew I could catch them and leave them. Every kid needs it. They need good influences around them, positive role models.”

He trained in the Miami pool with Olympian Grant Hackett, his great mate, where Hurst almost always finished second. And he trained under Denis Cotterell, the coach who embodies Gold Coast excellence.

“Denis had this culture,” Hurst says. “He had some of the best triathletes in the world, the best ironmen in the world, and some of the best swimmers in the world. We had Michael Klim, Giaan Rooney, Grant Hackett, Daniel Kowalski. The culture there was something that you didn’t want to miss.”

The Gold Coast climate is a given for excellence – to train all year round, unimpeded by the cold. Hurst is chatting upstairs at the Mermaid Beach Surf Club – on the beach below, son Koa is in a nippers session. It’s January, but it could be June.

Hurst credits the early age emphasis for water safety as another reason for the Gold Coast’s strike rate.

“I think it’s definitely the laid-back lifestyle that we are able to live here that creates that sense of security for individuals who come here from interstate who want to spend their time here and train,” he says.

Pearson, 38, a mother of two, tries to keep up when daughter Ruby, four, rides her bike to the Broadwater parklands a few kilometres from her Southport home. Few mothers could.

“With our climate, it keeps the kids outside as much as possible,” she says. “I feel like I’m living my life through my kids now. They’re doing everything I did as a kid and it brings back all those memories.”

Paralympian Alexa Leary has returned to the Gold Coast. Once “a kid running amok” here, she adores the “great coaches” and being “around so many active people”.

Sometimes the swimmers at Bond University are invited to jump in the pool and swim a leisurely 1500m. The clock isn’t running. It’s the elite sporting equivalent of splashing around for fun.

“There’s not a lot of physiological gain out of that, but it’s not the physiological gain, it’s the mental gain that you are looking for,” Mooney says. “It really does release amazing endorphins. It just sets you up for a kick-arse day, to be honest.”

*******

Comedian Mikey Robins felt rather pleased with himself. It was the mid-1990s, and his TV career was taking off.

He was about to deliver the valedictory speech at his former school, Newcastle High.

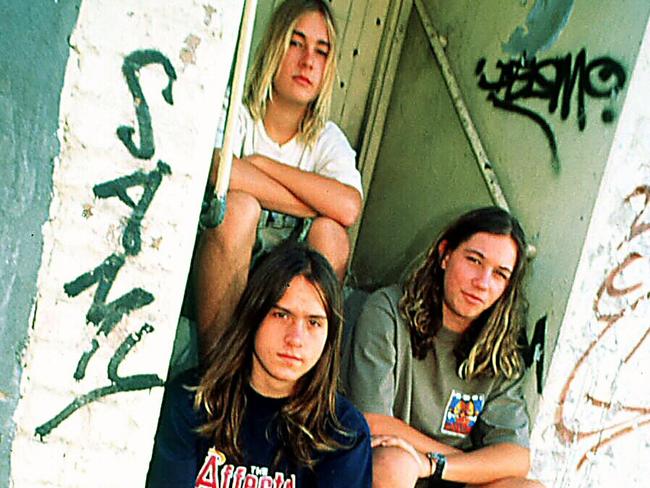

As he walked to the lectern, he scanned the front row – to see three departing students – Daniel Johns, Ben Gillies and Chris Joannou – better known, as Robins put it, as “about $30m worth of Silverchair”.

The precocious band members, for whom the school principal restructured study so that they could tour the world, didn’t talk about their mega stardom in the classroom.

They were just kids whose names would be added to the high-flying alumni of Newcastle High School.

The school’s front foyer boasts an honours board entitled Famous Faces – Their Dreams Started Here. Its breadth of talent is astounding.

There’s a Victoria Cross winner (Clarence Smith Jeffries), three Australian cricketers (Arthur Morris, Gary Gilmour, Belinda Clark), artists (Sir William Dobell, Fredric Bates) and an Australian of the Year (Patrick McGorry).

Actor Miranda Otto was dux of her year. Four times world champion surfer Mark Richards was also educated here. Born into the beach and the business of surfboards, he finished early, in year 11, to chase his destiny.

Current principal Janene Rosser hails an ethos of acceptance at the school.

Teachers aim to provide empathy and understanding. But the students are responsible for their future. “The decision making is in the student’s hands as they graduate” she says. “It’s not my life. It’s not our life. We need the young person to be very much in the driver’s seat.”

Rosser says that public schools are a reflection of their communities.

“Newy”, as its commonly called, is blessed with wave beaches and rockpools. Its parochial pride can be readily compared with Geelong, a collective instinct to look after your own, even if they move away.

Actor and theatre director John Bell grew up here in the massive industrial war effort of the 1940s.

Author and TV host Sophie Lee was raised here without a TV, apparently because her father preferred more intellectual endeavours.

NBA star Ben Simmons played his first representative basketball in Newcastle from the age of seven.

As Robins says: “No matter what I do, no matter where I go, no matter where I live, I’m still referred to as a Novocastrian. And I’m very happy about that.”

Alex McKinnon, of the Newcastle Knights, lost his NRL rugby league “identity” in 2014, when he was paralysed by a dangerous tackle in a game against Melbourne Storm.

He is a father of three, a proud citizen of Newcastle, and a product of small town values.

McKinnon has thought hard about the challenges and opportunities that get tossed your way.

His thoughts gel with cricketer Belinda Clark, who talks up the culture of volunteerism for elite achievement.

McKinnon reduces the magic ingredients to helping each other out. Nurturing a sense of improvement. Putting an arm around someone.

This explains the spirit of our nation, he says. Never giving up. And coming together.

Originally published as Four towns where our famous Australians come from