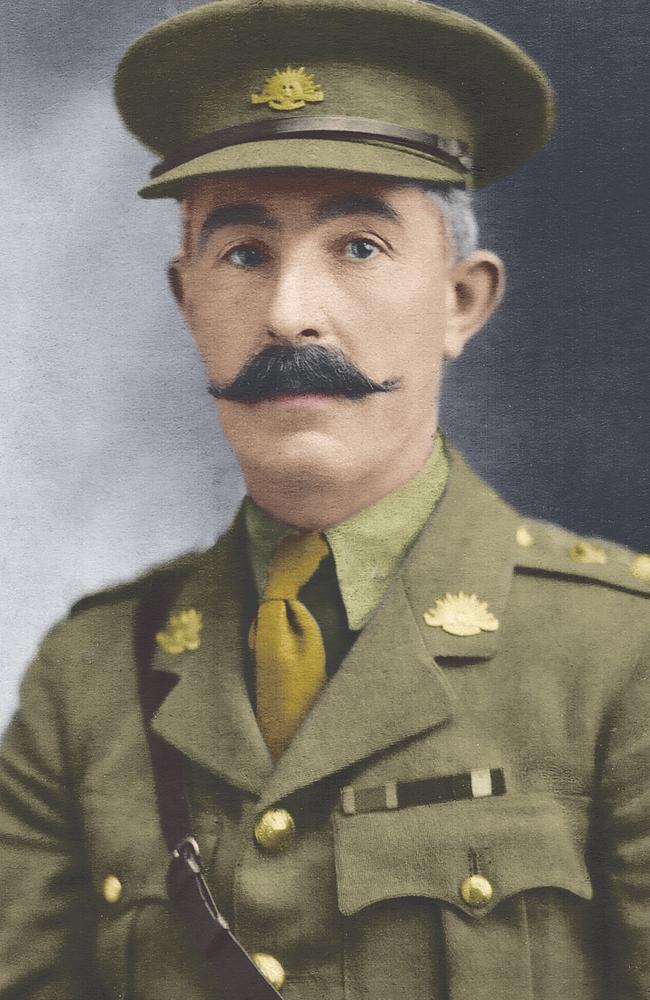

Executed Australian war hero Frederick Royden Chalmers endured so much loss — but his courage and determination never failed

A DEVASTATING decision by his mother-in-law that denied this Australian war hero access to his children has been laid bare —along with details of his execution 30 years later.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

LIKE many young boys in post-war Australia, little Roy earned pocket money by selling newspapers.

Among his hundreds of customers at a suburban Melbourne station, one stood out — a tall, kind man with a moustache who would periodically appear, talk to Roy for 20 to 30 minutes then vanish again for months at a time.

Then, one day, he stopped coming. It was not until years later that Roy realised who the man was.

Robert “Roy” Chalmers was the son of Australian WW1 hero Frederick Royden Chalmers. The tall man was his father — cut out of his children’s life in a crushing act by his former mother in law, but determined to see them nevertheless.

That determination carried Chalmers through an extraordinary life of service to his country, from the Boer War, through Gallipoli and the Western Front to World War Two — and his brutal execution along with four other Australians at the hands of the Japanese.

Without hyperbole he was an Australian hero, although his story is relatively unknown; and the recent discovery of his long-lost execution site and burial pit marks the start of a campaign to see Chalmers and the others recognised as such.

MORE: Lost Australians hero’ execution site and grave believed to be on Nauru beach

Chalmers was a farmer’s son, born at Brighton, Tasmania in 1881. Aged 18, adventure called and he headed to South Africa to fight in the Boer War — serving in the Tasmanian Imperial Bushmen alongside his cousin John Bisdee, one of the First Australians to earn the Victoria Cross in the three-year conflict.

By the end of the war Chalmers was a lieutenant — and he had a taste for military duty, although he returned to civilian life and a job with the state railway company in Victoria.

In fact, life was looking up: he married Mary Bennett in 1910 and they had three children. But just as suddenly, the first in a line of personal tragedies struck Chalmers — events that could have felled him but through which he somehow kept forging his way.

In 1913, both his mother and his youngest sister died from illness. A year later, as the drums heralding war rolled around the world, Mary was taken by pneumonia. Her Irish-born mother was given care of the children — and the stage was set for an ideological and personality clash that Chalmers would lose.

Historian Scott Seymour, who has written a book about Chalmers aptly titled No Turning Back, relates that while the Boer War veteran saw his duty as re-enlisting for the Empire, his mother-in-law had an intense hatred of the British as a result of her Irish heritage.

“She told Chalmers that if he went off to fight for Britain he wouldn’t get his children again,” says Seymour. “He followed his calling — and that’s what happened.”

When he came back, Chalmers barely saw the three. Seymour relates that the girls had vague memories of him trying to visit their house but they did not really know who he was and hid in confusion. Roy’s railway encounters, two or three times a year, were pleasant but hardly satisfactory.

The intervening five years had not been easy on Chalmers. He had lost his little brother Geoffrey, a 15-year-old naval cadet killed when a German U-boat sank his ship the Aparima; and while Chalmers had remarried overseas, his first baby from that union died of diphtheria at the end of the war.

“He had gone through so much, it is just extraordinary how he kept going,” says Seymour.

A clue lies in Chalmers’ refusal to give up, documented on the battlefield.

Starting WW1 as a private once again, in South Australia’s 27th Battalion, he served on Gallipoli then the Western Front. His extraordinary soldiering ability was recognised early and he began a meteoric ascent through the ranks that would see him end the war in command of the unit, as lieutenant-colonel and a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George.

As commander of the 27th he was loved by his South Australian men, and understandably — he led from the front, earning the Distinguished Service Order for bravery in one charge when he captured several trenches and prisoners at the point of his revolver.

He was fiercely protective of them in return, writing at the end of the war that his relationship with the SA soldiers was the “finest association of my life”, noting that their chivalry “commanded the everlasting respect of the women and children of France and Belgium” and adding: “It has been my privilege to rub shoulders with men who were endowed with the finest principles of manhood.”

Reading out his citation for that DSO action in August 1918, Seymour says: “Just that alone conjures up a scene in a movie that many would assume to be fiction.”

That determination and selfless courage would be demonstrated again in WWII, in the final chapter of Chalmers’ extraordinary life — one again marked by joy, hope and desperate loss.

After WW1 Chalmer and new wife Lenna, who he had met in London, returned to Tasmania. They had four daughters; and after 18 years of farming and work with the Returned Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Imperial League of Australia and Boy Scouts, Chalmers was chosen as administrator of the Australian mandated territory of Nauru, where he relocated with Lenna and the family.

It was an idyllic life for the children of government staff there; and Chalmers — now white-haired but still moustachioed — was a hit with the locals both for his easy personality and the practical changes he made: introducing better pigs and mosquito-eradicating fish. Nauruans are still named after him today.

Yet within a year of his appointment, the world was hurled once more into the horror of war. And this time, horror was on Australia’s doorstep; in the form of a brutal, rapacious, merciless foe that wanted all the South Pacific’s treasures — Imperial Japan.

The prizes on Nauru were its potential as an air base and the phosphate mining operation; and Australia was not adequately equipped to defend it. The first attack came from passing German ships, who shelled the mines, prompting Chalmers to storm along the waterfront shouting defiance at them.

The threat from Japan’s entry into the war was far greater. The tiny Aussie garrison was to be withdrawn, along with all civilians and their families, in early 1942.

Yet Chalmers and four others argued that Australia could hardly abandon the native population and expect to return after the war — so Canberra granted their request to stay.

“Chalmers obviously knew what war was and how brutal it could be,” says Seymour. “But I do not think there was any notion of how horrendous it could be if the Japanese invaded.

“Chalmers would have hoped that it would be a situation where he could negotiate and deal with the Japanese and come to some sort of agreement to help the natives. He was in for a rude shock.”

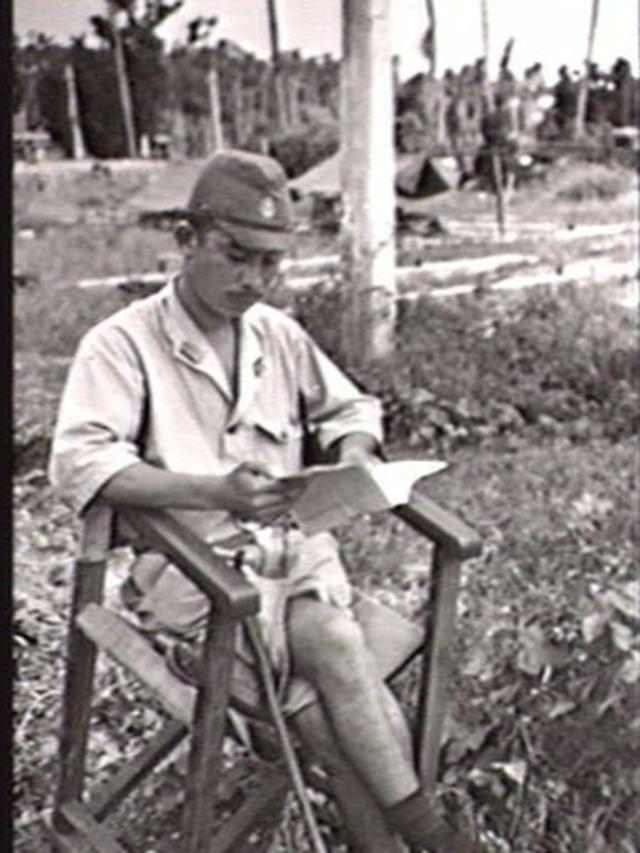

The Japanese landed on August 26, 1942 and set about a vicious occupation as elsewhere in the Pacific. Natives were killed, raped, forced into slavery and deported to inhospitable atolls; an entire colony of leprosy victims was loaded onto a boat and shelled to death.

Chalmers and his companions — NSW-born WW1 light horse veteran William Doyle, 47, plus Victorian trio Dr Bernard Quin, 48, medical assistant Wilfred Shugg and 44-year-old engineer Frederick Harmer — were imprisoned and, like everyone on the 21kmsq island, put on starvation rations.

Chalmers never knew that within weeks of the occupation Lenna, who was sick at home, died; leaving eldest daughter Winifred, who adored her father, holding out on behalf of the family for news that never came.

The five were moved between various locations; and six months later were being kept in a house, where Quin was very feeble. On March 25, US bombers launched their first raid on Nauru — as shown in Angelina Jolie-directed movie Unbroken — and in the panic, the savage Japanese second-in-command, Hiromi Nakayama, decided the five must die for fear the charismatic Chalmers might incite rebellion among the natives.

Accounts of the execution vary in exact detail.

An islander witness said he saw a Japanese officer with a sword summon the men from their house and behead them one by one, beginning with Chalmers.

“The Japanese with the sword called for one of them to step close to him. Colonel F.R. Chalmers stepped forward and I saw him stoop over and the Japanese raised his sword with one hand and brought it down on the Colonel’s neck. His head was severed from the rest of his body. Then Doctor Quinn, Mr. Doyle, Mr. Harmer and Mr. Shugg stepped forward one at a time and the Japanese with the sword went through the same motion until all the men mentioned had all been decapitated. After the execution I saw each body being carried to the motor truck and placed in a large box therein.”

However Japanese soldiers said they were taken to the beach, stood in front of pits in the sand and executed.

“The officer in charge struck the first man across the neck with his sword and at the same time the soldiers standing behind bayoneted the other men in the back,” says Seymour, who has ploughed through the post-war testimonies.

“Into the hole they went. One of the Japanese soldiers said one of the men in the hole was muttering something. The commanding officer told him to take his revolver and shoot the man in the head. The first shot missed, the second shot hit him. Another of the men started moaning; but they just filled the hole in.

“It was a horrific and pointless exercise.”

Interestingly, Nakayama told his superiors the men had been hit by a bomb while being moved to safety during the air raid; but after the war his immediate subordinate Sasaki Saburo, tracked down in Tokyo, confessed the truth to allied investigators.

Nakayama was sentenced to be hanged by an Australian Military Court trial in Rabaul in May 1946 and Saburo was jailed for 20 years.

With the truth now known and justice meted out, one thing remained: to bring the men home to their families. And that is where an extraordinary thing happened: it appears the case was simply forgotten.

“It’s like someone dropped the files behind a cabinet,” says Seymour.

For 70 years nothing happened, until Tasmania-based Seymour began researching Chalmers’ story. Dogged digging in government archives eventually turned up a map based on Saburo’s confession showing the location of the death pit; and an on-site investigation by the Unrecovered War Casualties unit of the Australian Army narrowed it down still further.

Yet the Department of Foreign Affairs is not in a position to fund the recovery of any remains, although it funded the initial investigation and will provide logistical support.

Experts led by Sydney-based archaeology firm Extent Heritage are prepared to do the job unpaid; they estimate it will cost $35,000 — much less than the DFAT/Defence ballpark of $50,000-$150,000 — and are hoping that benefactors may make up the shortfall; one has already offered $11,000.

While there is a memorial on Nauru. the sacrifice of the five is not recognised in any official capacity in Australia — and families, including Quin’s surviving children and Chalmers’ grandchildren from both marriages, want that to change.

For in the story of Frederick Royden Chalmers there is one final swing of tragedy to joy to relate.

Seymour’s investigations have brought the two sides of the family together again. Today (Sunday, March 25) up to 25 members of the Victorian clan will join the Tasmanian branch at Bagdad near Hobart to unveil a plaque in Chalmers’ memory.

It is not the same as recovering his body; and it will not help the families of Quin, Shugg, Doyle and Harmer; but it is an important step in saluting an Australian who does not deserve to be forgotten.

And in a large way it fulfils one of Chalmers’ last wishes.

Just before his children left Nauru, the 62-year-old sat down with Winifred on the beach and said: “I’ve had a busy life; there is one thing I want to do after all this is over: sit down at the dinner table with all my children.”

Seventy-five years on, Chalmers will be there in memory only; but as his grandchildren and great-grandchildren break bread together following the ceremony tomorrow, memory will suffice.