‘Doing nothing is not an option’: Dire warning on Australia’s worsening housing crisis

Australia is in the grips of a worsening crisis that’s affecting more and more people – and experts warn urgent action is needed to avoid catastrophe.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Top economists have issued a dire warning about Australia’s crippling housing crisis, urging governments to take drastic actions to avoid a total catastrophe.

Alongside soaring home values, rental markets across the country have experienced unprecedented price rises over recent years and vacancy rates are now at record lows.

In a stark illustration of the level of desperation being felt by many, a homeless man on Monday pleaded with a judge to send him to prison because he couldn’t find anywhere to live.

David Ambrosius was being sentenced for lighting a fire in an abandoned motel in Geraldton, WA, last year when he suggested copping two years behind bars, in a bid to have a roof over his head.

The 48 year old said he would reoffend if released. He was and he did – just hours later, causing property damage while trespassing.

Last year, 274,000 people sought help from homelessness services across Australia, with women and children among the largest groups.

But the group Homelessness Australia said support services had to turn away almost 300 people a day on average in 2022-23, equating to about 108,000 requests not being met in a single year.

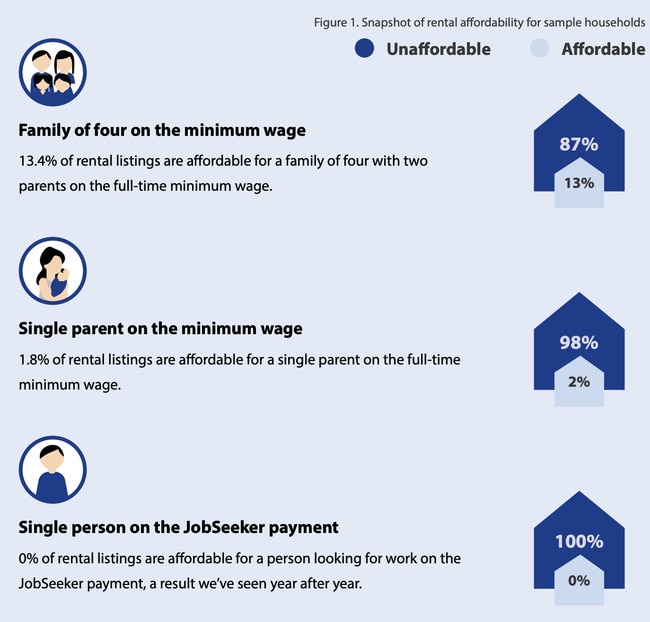

A recent report warned that as many as 40 per cent of low-income renters are now at serious risk of having nowhere to live.

Urgent action needed

This week, a panel of 49 of the country’s best financial minds were probed by the Economic Society of Australia on what measures might tackle worsening housing and rental affordability challenges.

None of them supported the view that the free market should be left alone to function independently.

Instead, a series of interventions — from ditching support schemes for first homebuyers to scaling back generous tax perks for landlords — were proposed.

“About two-thirds of the experts polled picked ‘ease planning restrictions’ as one of the most important fixes. Almost as many picked ‘provide more public housing’,” Peter Martin, a visiting fellow at the Crawford School of Public Policy at Australian National University said.

“About one-third wanted to ‘tighten negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions’, which was a policy Labor took to the 2019 election. Another third wanted to ‘replace stamp duty with land tax applying to family homes’.”

In analysis for The Conversation, Mr Martin said the results also revealed other popular ideas, such as encouraging the construction of prefabricated homes, accelerating the training of builders, and boosting skilled migration for foreign tradies.

“Asked whether it was more important to restrain rents or home prices, a majority of those surveyed (58 per cent) backed action to restrain rents, although several said action to restrain prices would flow through to rents,” he said.

Time for tax change

Median rent prices at a national level have surged by almost 40 per cent over the past five years, although that figure in particularly-strained areas is much higher.

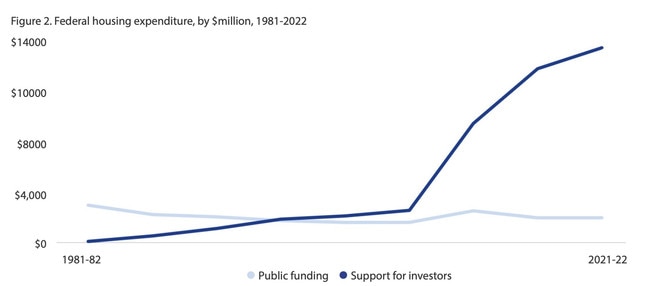

Professor John Quiggin, a senior fellow at the University of Queensland, said relying on property investors to boost housing stock had not worked.

“We need to move away from reliance on individual landlords to provide rental housing,” Professor Quintin said.

At the 2019 election, then-Labor leader Bill Shorten put a series of significant but contentious housing policies to the electorate.

They included an overhaul of generous negative gearing tax breaks and the capital gains tax discount on offer.

Labor’s shock defeat was attributed in part to the unpopularity of those platforms.

Kosmos Samaras, director of strategy and analytics at polling research firm Redbridge, said voters might be more inclined to accept dramatic reform this time around.

“Based on what we have seen to date, the majority of Australians may consider supporting some reform that limits an ability to negatively gear a property beyond one property,” Mr Samaras said.

“So, if you own one investment property, you can negatively gear that property, but not beyond that.”

Mala Raghaven, an associate professor in the University of Tasmania’s School of Business and Economics, said the perks on offer to landlords are unfair.

“Over time, housing has shifted from a necessity to a speculative asset, with negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions disproportionately benefiting a particular segment of society,” Ms Raghaven said.

“It’s crucial to support those in need and ensure that housing returns to its rightful place as an essential good rather than a speculative commodity.”

Australia’s shameful legacy

Over recent decades, the country’s pool of social and affordable housing has dwindled as states and territories slashed investment in favour of supporting the private market.

Shock figures compiled by The Guardian earlier this year indicated some 190,000 households are on waitlists for social housing across Australia.

In New South Wales alone, more than 57,000 households are on the waitlist, with 8600 of those deemed as urgent.

In Greater Sydney, the typical wait has blown out to three years, while in some parts of the state, it is more than five years, according to Homelessness NSW.

The rise in homelessness and worsening housing affordability are cause for serious alarm, Ms Raghaven said, with the consequences now starkly evident.

“Australian policymakers must confront this issue with the seriousness and urgency it demands,” she said.

Like the majority of other economists on the panel, Ms Raghaven called for “a significant and sustained investment in public housing”.

“It’s crucial to support those in need and ensure that housing returns to its rightful place as an essential good rather than a speculative commodity.”

Social housing comprises less than five per cent of the country’s total housing stock, Professor Guyonne Kalb, a fellow at the Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research at the University of Melbourne, said.

“Substantial additions to the social housing stock are needed to reduce the current long waiting times for social housing,” Professor Kalb said.

“Even for people in desperate need, the waiting times can be unacceptably long.

“To be able to increase the number of social housing dwellings and housing supply more generally, planning restrictions need to be reassessed as these currently hold up or even completely stop too many new housing developments from going ahead.”

The Federal Government is finalising work on a new National Housing and Homelessness Plan, which it has committed to releasing by the end of the year.

The 10-year strategy will establish “a shared vision to inform future housing and homelessness policy”.

There is already extensive recent information at the government’s disposal — with two parliamentary inquiries and a Productivity Commission review conducted since 2021.

Among the recommendations made were early intervention and prevention measures, reducing the shortfall in social and affordable housing, and prioritising those experiencing long-term and chronic homelessness for supporting housing.

Experts say governments already know how to end homelessness and just require the will to do it.

Grants don’t help

The so-called Great Australian Dream of homeownership is falling further and further out of reach for young people, with the gap between median house prices and incomes soaring from five years to eight years in the past 20 years.

The time it takes to save the required 20 per cent deposit to secure a mortgage is now about a decade.

Despite that, many of the experts polled said support schemes for first homebuyers served largely to increase demand for real estate, at a time when supply is seriously constricted.

Originally published as ‘Doing nothing is not an option’: Dire warning on Australia’s worsening housing crisis