Australia’s My Health Record: The debate so far and what you need to know

AUSTRALIA’S health care system is entering the digital age with a new approach to record keeping, but privacy and security concerns are raging. We explain how the My Health Record debate has unfolded so far and ask you to have your say by VOTING NOW.

- Elisa Black: Why I’m opting out of My Health Record

- Greg Hunt moves to allay My Health record fears

- Opinion: ‘Opting out of My Health shouldn’t be this hard’

- Top Australian doctor ditches his My Health Record

- Tim Kelsey grilled on My Health Record system

WHEN it comes to people protecting their privacy, few areas get to the heart of the matter faster than safeguarding sensitive medical records.

So when a new Federal Government agency suddenly announced everyone’s medical records would be uploaded to a mega-database before the end of the year, it was a bit of a shock to the system.

Many people responded with fear and suspicion to the $1 billion My Health Record plan, arguing the database would be vulnerable to hackers and open to all kinds of abuse if the information fell into the wrong hands. Especially sensitive information such as abortions, drug addictions, mental health problems and sexually transmitted diseases.

Their fears seemed well-founded when it became clear the My Health Record legislation allowed police, the Australian Taxation Office, Centrelink and other government agencies to access the records without a court order.

It was embarrassing for Health Minister Greg Hunt, who initially claimed police access was only possible with a court order, until the Parliamentary Library revealed the true picture.

And time is running out to address the concerns and convince Australians that their medical records are in safe hands.

People have until October 15 to opt out of the system by completing an online form on the government’s My Health Record website.

If people don’t opt out, the Government will create a record for them, which about 13,000 health professional will then be able to access.

The idea behind My Health Record is a simple one.

The Government believes it will save lives by providing medical staff with better access to patients’ records, including test results, medication details, allergies and previous medical conditions.

The plan originally had the support of a wide range of medical experts but cracks are starting to appear.

The new boss of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP), Dr Harry Nespolon, this week revealed he had opted out of My Health Record.

“I opted out because the My Health Record should be about my health and is not for government agencies or police,” he said.

Former Australian Medical Association president Professor Kerryn Phelps has also raised concerns, saying allowing police access to My Health Record details would undermine trust in doctors.

Dr Nespolon met with Mr Hunt earlier this week to discuss his concerns.

He has since written to RACGP members to inform them that Mr Hunt has agreed to strengthen the system’s privacy.

Labor Leader Bill Shorten has vowed to opt out of the system if the problems are not addressed.

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has promised to fix privacy concerns with the My Health Record, while slamming the Opposition Leader for considering opting out.

Australian Digital Health Agency chief executive Tim Kelsey has argued that claims about potential privacy breaches with the My Health Record system amounted to “dangerous fearmongering”.

He said patients would be able to control their records and could remove documents entirely or restrict access to certain providers.

“It will reduce harm caused by medication errors because people and their healthcare providers will have access to important information about medicines and allergies,” Mr Kelsey said. “This could save your life in an emergency.”

Aside from changing the dynamic in emergency situations, when first responders now have to treat someone who may be unresponsive or unconscious while having limited access to information, the other benefit of the new system would be to those with chronic and complex health conditions, such as the elderly or people living with mental health issues.

“It will enable all of their clinicians to see the same healthcare information,” Mr Kelsey said. “This should also reduce avoidable hospital admissions and the unnecessary duplication of pathology and imaging investigations.”

Almost six million Australians have already signed up to My Health Record. Some were early adopters who jumped on board years ago when the database went by another name: Either the Personally Controlled Electronic Health Record or the eHealth record.

Most registered themselves or their children, although many of those children would have been registered from birth when their parents first enrolled for Medicare.

About one million people were added to the system in 2016 during the Department of Health’s opt-out participation trials.

Those trials, held from March to October in the Nepean Blue Mountain region of NSW and in Northern Queensland, were the dress rehearsal for the latest debate.

An evaluation of the trials found people’s initial concerns about the privacy of their health records soon faded.

“Once the benefits of the My Health Record system were clear, nearly all focus group participants said that their concerns about security and privacy, or about the fact that a My Health Record had been created, disappeared,” the report states.

“They most often said that, while they thought that no computer-based systems were totally safe, on balance they thought that the benefits to them, their families and the health system far outweighed those risks.”

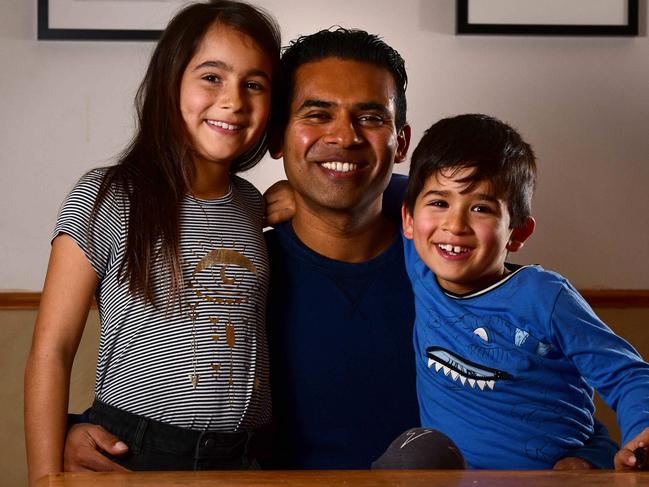

Niranjan Bidargaddi, an Associate Professor of personal health informatics at Flinders University, started using My Health Record a few years ago, then added his children, Elke, 9, and Ravi, 6, to the database last year.

While he recognised that concerns over security, privacy and incomplete records needed to be addressed, he believed the system’s benefits far outweighed the risks.

“I think people should not make decisions to opt out in isolation, they should consider the risks alongside the benefits then make an informed choice if they still feel strongly about it,” he said.

“There is a concern that people might be getting scared of the system unnecessarily.”

The question is whether the storm will pass before the deadline of October 15, or perhaps the Government will suspend the rollout until privacy concerns are addressed.

Either way, it seems that My Health Record needs a thorough check-up and rigorous clinical examination before it can be given the all-clear for use across the nation.