Best of Andrew Rule: What stopped Queen St massacre gunman Frank Vitkovic killing more victims

Queen St killer Frank Vitkovic wanted a gun that could fire bullets as fast as he could pull the trigger to carry out his chilling mission. And if he'd gotten what he paid for, many more lives would have been lost.

VIC News

Don't miss out on the headlines from VIC News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

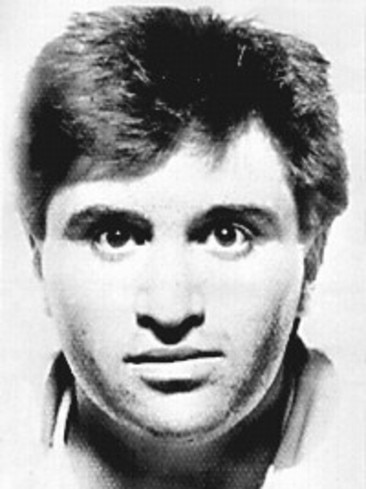

Of all the disturbing things about mass killers like Frank Vitkovic perhaps the most disturbing is this: most of them seem so ordinary. They pass among us without any need for disguise until the fatal day comes when they reveal that ordinary is not necessarily normal.

Vitkovic was a Law School dropout who walked into a Melbourne office building on a hot Tuesday afternoon and started shooting.

He killed eight people — one more than the coward of Hoddle St, Julian Knight, had murdered a few months earlier. Terrible as it was, the slaughter could have been much worse.

30 years since Queen St massacre in Melbourne

Queen St killer Frank Vitkovic’s evil mission

Close to 1000 people worked in the 18-floor Australia Post building at 191 Queen St. Vitkovic had a sawn-off assault rifle and 10 magazines loaded with enough rounds to shoot not just the old school friend against whom he nursed an imaginary grudge, but dozens more people as well.

Police later found 41 spent shells and 184 live ones, chilling proof that the failed law student was out to settle a score that existed in his mind only. It was just dumb luck that the toll of dead and injured was not many times higher: it turned out that Vitkovic had been “cheated” when he had bought the .30 calibre carbine a few weeks earlier. The M1 carbine used by US military from World War II until the Vietnam War is a semiautomatic that can notionally shoot 12 bullets a second — that is, as fast as someone can pull the trigger.

But, as a coroner would later hear, the trigger of Vitkovic’s weapon was faulty, its spring so weak the trigger had to be manually pushed back into position before each shot. Result: instead of spewing out a stream of bullets, it was effectively reduced to a “bolt action” requiring a movement by the shooter to set up each shot.

Ex-detective admits stealing Queen St killer Frank Vitkovic’s diary

Shots fired’: the emergency response during the Queen St massacre

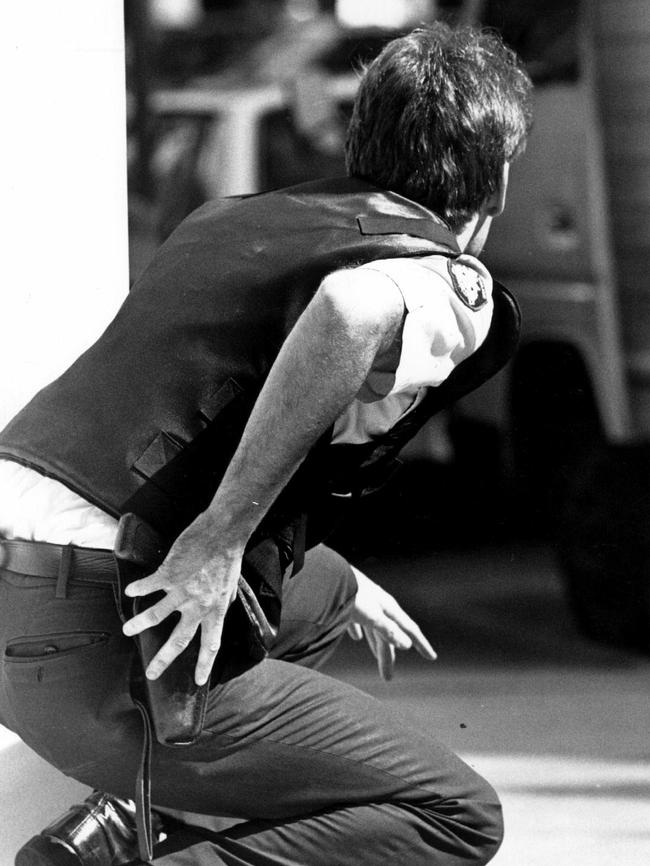

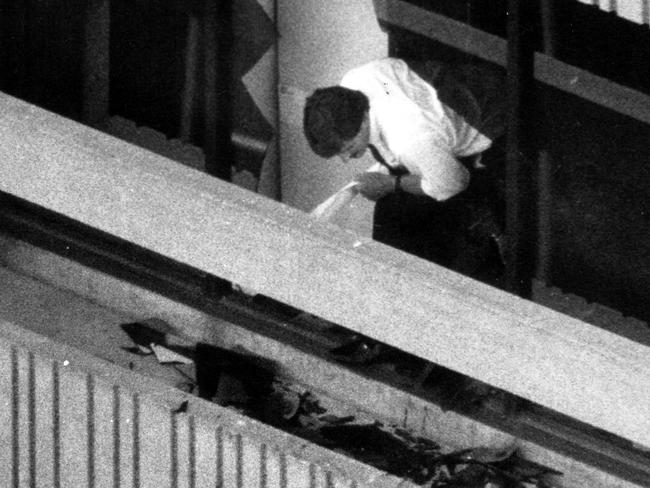

The enforced pause between shots meant potential victims could flee and hide because Vitkovic’s progress was much slower than it otherwise would have been. Security film footage of the rampage shows him repeatedly looking down at the weapon as he fiddles with it. This not only gave dozens of people the chance to avoid him — it gave two brave men a chance to tackle him.

Frank Vitkovic was born on September 7, 1965, second of two children of post-war migrants Drago Vitkovic, a Yugoslav, and his wife Antoinetta, who was Italian. Frank and his older sister were brought up in the hard working family’s neat house in Preston.

An early sign that young Frank was a little different from his peers was his obsessive edge, which manifested itself in studying many hours a night while he attended a Catholic college.

Puberty apparently amplified flaws in his personality.

In 1983, when he was 17, he was caught lying on the floor of Northland shopping centre, apparently looking up a woman’s dress. Police were called and the troubled teenager was sent to a psychiatrist — the first of several times he would be counselled for hidden depression and anger.

On one hand, he could come across as a witty, intelligent young man. But behind the mask he held up to the world he was growing more intense as his mind squirmed with fantasies and delusions that were getting harder to control. He also displayed what might now be labelled as signs of the autism spectrum: he had a freakish ability to recall and recite facts and figures, was noticeably awkward with girls and didn’t make friends easily.

By the time he left school he had become an oddball perfectionist who hated to lose. His male friends, none of them close, dubbed him “Viko” and “Vik the Dick” or the “stats man”, names that subtly ridiculed him.

Vitkovic studied with furious intensity and got into law at Melbourne University in 1984, a course that put him under pressure to study even harder. On his first day at university, he drew odd looks when he turned up to lectures in a collar and tie. He played tennis and snooker with the same manic edge as he studied, practising by himself for hours. If he lost a game, he would go silent, not that anyone much cared.

If there was one trigger point that stood out, looking back, it was when Vitkovic injured his knee while running. The injury stopped him playing tennis and sent him into a spiral of depression from which he never recovered. He put on weight, stopped shaving and lost interest in studying. He was suspended from the Law faculty and switched to Arts after handing in an essay that was a weird diatribe advocating capital punishment for civil libertarians.

He was referred to a university counsellor who noted he was fixated with violent fantasies that focused on hurting others and himself. The perfectionist who could not live up to his own high standards now felt his life was meaningless.

The counsellor referred Vitkovic to a psychiatrist but could not force him to attend. He dropped out of university altogether but sometimes turned up on campus, overweight and brooding, guilt-ridden and angry.

At a 21st birthday party in 1986 he told an old friend he felt he could “get a gun and end it” but there seemed no reason to take him seriously.

The following year the same friend saw Vitkovic on a Preston street. “He was bobbing his head and talking to himself,” the friend said. “I had never seen him do that before.”

Meanwhile, Vitkovic had fostered an irrational hatred of a former schoolmate, Con Margelis, who had started work with the Telecom Credit Union after leaving school.

On October 8, 1987, Vitkovic applied for a shooter’s permit on the grounds, as he wrote on the application form, that he had “a desire to go hunting.”

A week later he paid a deposit on an M1 carbine at Precision Guns and Ammunition in Victoria St, West Melbourne. He returned five days later to pick it up with the 10 rifle magazines and 250 rounds of ammunition. He hid the weapon in his bedroom. At some point he sawed off most of the barrel so it was easily concealable in a sports bag or under a coat.

ON THE afternoon of December 8, Vitkovic visited Mary Cooke, the kindly receptionist at the university union building who often chatted to the lonely dropout. He looked dishevelled and was acting strangely. He told her he had “a job at the post office to do” then added that she had been “a lovely lady” to him and clasped her hands. She noticed that he kept looking down at a brown bag he had brought with him.

About 4.15pm he walked into the Australia Post building at 191 Queen St, where Con Margelis worked on the fifth floor. He must have taken the lift because two minutes later, Vitkovic asked to see Margelis at the credit union. When Margelis appeared, Vitkovic pulled the rifle from under his jacket, pointed it and pulled the trigger.

The gun didn’t fire because he hadn’t cocked it properly. Margelis ran back into the credit union, yelling warnings to other staff. Vitkovic climbed the counter and started shooting. Margelis hid in the toilets but his workmate Judy Morris wasn’t so lucky. Judy, 19 and just engaged, was shot dead.

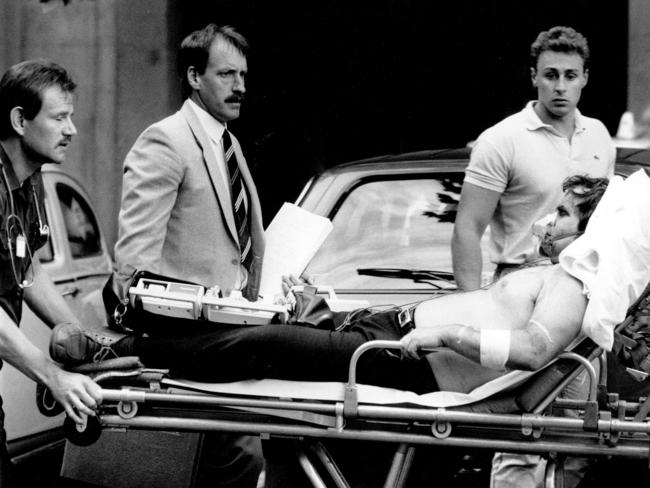

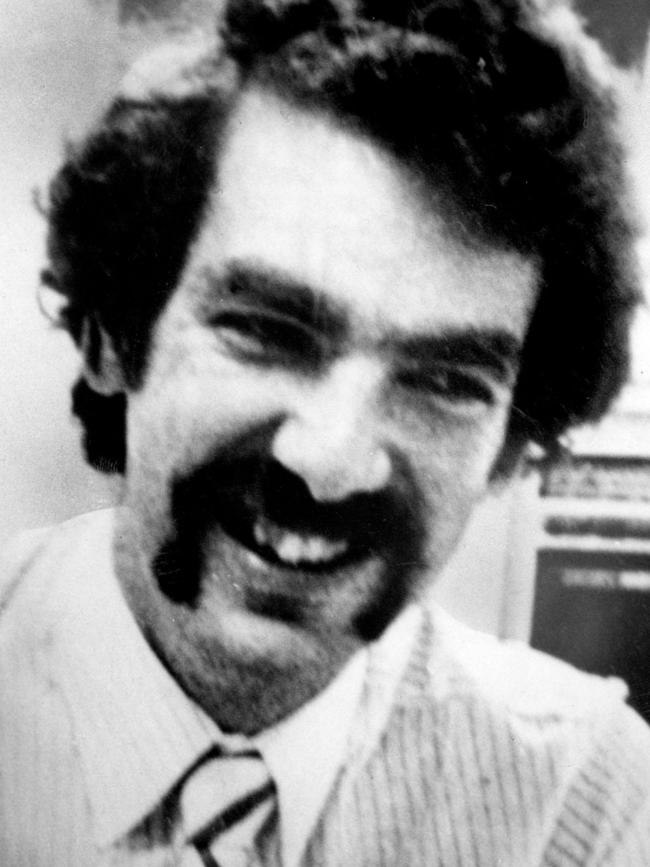

Vitkovic, apparently at random, went to the 12th floor and kept shooting. Then he went to the 11th floor, shooting everyone he saw. One of the wounded was Frank Carmody, who saw the gunman turn his back on a fellow worker, Tony Gioia, a quiet father of four.

Gioia, much smaller than Vitkovic, jumped on him from behind. Carmody, bleeding from a bullet in his back and other wounds, wrestled the rifle from Vitkovic and handed it to a woman co-worker who hid it in a refrigerator.

Vitkovic ran towards a window already broken by gunfire. A court later heard that the gutsy Gioia held his legs for a while but the madman kicked clear and fell. Police in the street below watched Vitkovic’s body plunge to the pavement.

“Until that afternoon,” this reporter would write later, “when circumstances brought them together, no-one knew that Frank Vitkovic or Tony [Gioia] had it in them. One a crazed killer. The other an unassuming hero. It’s the quiet ones you have to watch.”

Originally published as Best of Andrew Rule: What stopped Queen St massacre gunman Frank Vitkovic killing more victims