From Ginger Meggs to career criminal: The remarkable life of Carl Synnerdahl

AT the age of four, Carl Synnerdahl stole the milkman’s draught horse and tried to hide it in his bedroom. It would be the beginning of 40 years as a jetsetting career criminal. This is his incredible story.

At the age of four, Carl Synnerdahl stole the milkman’s draught horse and tried to hide it in his bedroom. It was the mischievous little tyke’s first brush with the law. Over the next 40 years, he would be in and out of jail — mainly for bank robberies. At one point, he was on Interpol’s 10 most-wanted list. Then, in the ‘80s, he seemingly disappeared off the face of the Earth. NATHAN DAVIES tracked him down and discovered a man at peace with himself — and with a remarkable story to tell.

IT’S 1946 and four-year-old Carl Synnerdahl is planning his first major heist. He’s a little bloke with a big attitude and he’s got his heart set on pinching one of the big old draught horses kept in the dairy at the bottom of Dickson St in the inner-city Sydney suburb of Newtown.

It’s an audacious plan — the Synnerdahl family’s tiny terrace house is no place for a huge horse — but young Carl isn’t thinking about that. He just wants a pet and what better pet than the milko’s horse?

“I planned the whole thing,” Carl, now 73, says from the kitchen of his modest home in South Australia’s Barossa Valley winegrowing region.

“Every day, horses used to come up and down the street — the milkman, the breadmaker in the baker’s cart, the clothes-prop men, who used to sell those big poles that you held your washing line up with, fish-sellers, clothing people. Everyone driving a horse and cart and there were no department stores as such.

“At the bottom of Dickson St was a big paddock and it used to be called Bomaderry’s Dairy. They had about 20 draught horses, so I jumped the fence and untethered him and said ‘Come on, mate’. It didn’t know where I was going to take him and then I thought ‘I’ll take him home’.

“I dragged him up the street and I got him to the house and checked out the back and Mum was doing the laundry so I brought him into the house. I just wanted him as, you know, something for me to have.

“So I got him all the way down to the kitchen and Mum was like ‘What’s that noise?’. When she came in, well, there was hell to pay.

“I said ‘I found him in the street, Mum’, and she said ‘Yeah, right!’ She knew where it come from, so I went back down with Mum and seen the bloke. He said, ‘Oh, thanks for bringing my horse back’.

“He knew what really happened but he still gave me a ha’penny and said, ‘If you see any more roaming about just let me know’.”

In the late 1940s, the working-class streets of inner Sydney are young Carl’s home: Newtown, Glebe, Surry Hills, Erskinville — “I knew every street, the whole box and dice”.

As a real-life Ginger Meggs — a hustler in short pants riding the running boards on the trams and sneaking into the movies — he sells old newspapers to the butcher and bludges a few pennies from the crowd during the frequent post-war parades. Anything to avoid going to school — and if you can make a couple of bob then that’s a bonus.

It’s the age of the free-range kid and the streets are their playground. It’s an age when a boy who can’t even see over the bar can buy a bottle of brandy.

“My uncle Carl, who’d come back from World War I, was still in bed and sick and dying,” Carl recalls.

“He wasn’t allowed to drink but he used to get me to go to an old bar on Glebe Rd at five and six years of age. He’d get me to sneak out of my great-grandmother’s house and go to the bar. “They knew me there because I was in and out so often and I’d buy him a little bottle of brandy. Then I’d run back and jump the back fence and sneak it up to him. That was my sort of start in things, if you know what I mean.

“I look back now and laugh my head off that a five-year-old could walk into a bar and be given a bottle of brandy.”

Unsurprisingly, schooling isn’t a high priority for Carl, and Grade 5 is the extent of his formal education although later, during one of his many stints in prison, he would complete an education degree.

He starts at St Pius’s Catholic school and then when, the family moves to Lakemba, he goes to St Theresa’s, followed by the De La Salle Brothers school at Five Dock.

It’s here he is exposed to the cruelty that turns him off school for life.

“There was a guy called Brother Peter who would flog the crap out of me,” Carl says.

“He had piece of lino that he’d hit you with and he got me every day because I was a couple of minutes late getting off the bus — but that’s what time the bus arrived.

“I was out in the playground one day and I must have said something and this Brother just grabbed my face and twisted it. I had this big bruise and went straight home and Mum saw it and I told her what went down.

“She said, ‘Righto, come on’ and we got on the bus and went back down to the school.

“She pointed to one of the children in the front of my class and said, ‘You come up here and stand there and look after the class while I talk to Brother Peter’.

“We went on the veranda and, without him saying a word, Mum’s thrown a right hook straight on to his chin and decked him.

She said, ‘If you ever touch my son again this is the least that’ll happen to you’. “After that I went to Five Dock Primary, which is where I wanted to go anyway.”

It’s a short stint, though, because 12-year-old Carl soon decides that school isn’t for him and that it’s time to go out and make his way in the world.

With two quid in his pocket, he decides to hightail it to Queensland.

“I went down to Central Station and bought a ticket and I remember whatever change I had was enough for a packet of chips,” Carl says.

“By the time the train got to Brisbane, it was nearly night time.

“There were three garages nearby on three corners and I broke into all three of them and filled my pockets with coins.

“Then I got something to eat, sat in the park and dozed off.”

The next morning, alone and more than 900km from home, Carl decides that the best thing to do is go to the pictures.

He recalls meeting a bunch of like-minded kids who tell him about some stablehand work — and he ends up working for legendary Queensland trainer Bart Sinclair.

“In those days, you could leave home at 12 as long as you had a job and a place to stay,” Carl says.

Eventually, word gets around about Carl being so far from home. Police come calling and tell him that although he’s legally old enough to leave home he should consider returning to Sydney where his mother, Emma, and tram worker/SP bookie father Eric had feared the worst, not having heard from him for weeks.

He’s put on a plane back to Sydney where he manages to stay out of trouble. For a while.

The years pass and, by 1962, Carl’s biggest offence — that he’s been nicked for, at least — is stealing a newspaper and a bottle of milk. That’s all about to change.

“I hooked up with three blokes and we did an armed robbery on a service station,” he says. “And that’s when I got caught and I got 4½ years.”

It was his first taste of

prison. By the time he goes straight in the 1980s he’ll have spent 21 years behind bars.

Jail is a place that Carl will become very used to; a place where he’ll end up putting his keen eye for detail and entrepreneurial skills to good use.

On that first night in Long Bay, however, he’s scared.

“There were probably 20 screws (warders) there and it was raining heavily,” he

recalls.

“We were made to line up on a yellow line. They’d threaten us — ‘You do that and you do this or we’ll f---ing bash ya’ — I was shitting myself.”

The newly-married Carl has a young daughter named Donna and a life outside that he fears will fall apart if he stays inside. He starts plotting his escape.

“I did the right thing so they moved me into an easier prison (Goulburn) that I knew I could escape from,” Carl says.

Once in the Southern Tablelands town, he starts working on cutting through his bars with a smuggled hacksaw blade. It’s a noisy job but, one day, a sudden downpour helps to mask the sound and eventually he’s pulled one bar back far enough to squeeze through. He gets across the yard unseen and manages to clamber over a 6m-high wire fence before using a rope to get over the main prison wall.

Now free, Carl breaks into a factory next to the prison, steals a truck and drives through the night to Wollongong. The police are on his trail almost instantly and a shootout ensures. At least that’s how it was reported.

Carl has a different story.

“There was no shootout,” he says. “They shot at me, but I never had a gun.” Back behind bars, two years are added to his existing sentence of six years for the escape.

This time he’s in Parramatta, a prison he’ll come to know intimately. So intimately that, Carl says, he was basically running the joint.

“Parramatta was my jail,” he says. “I put a crew together and we took over the bookmaking. Took over the canteen. Took over the mail.

“I was able to take over all the business in the jail. People were scared I was going to stab them. I lived very comfortably in prison.”

Eventually Carl serves his time at Parramatta and is freed. “And that’s when I really cut loose — robbing banks and flying overseas,” he says with a nostalgic smile.

Carl robs four banks — in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane. They’re well-planned hits and net him tens of thousands of dollars, enough to spend his time out of jail in the 1970s living large in the party centres of Asia — Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo.

His raids follow the same basic pattern — make an appointment to see the manager, threaten him with your gun, lock the staff in the safe, take the cash, and get on a booked flight for overseas.

“My first bank job was in Elizabeth St, Brisbane — the main branch of the Commonwealth Bank,” Carl says.

“I never walked into a bank and put a gun over the counter and said ‘give me your money’. That was ludicrous. As was taking along other people who might do something you don’t want them to. So I always worked alone.

“It would be about 2.30 in the afternoon because the banks in those days used to close at about three. I’d know if there had been a delivery that day, where the keys were to the vault and who had them. I had it all worked out.

“I’d sit everyone down and say, ‘Look, I’m not here to hurt anyone, so don’t create any problems for me ’.

“I’d say ‘I’ve gotta get away from here. If one of you wants to be a hero, I’ll shoot you’.

“I used to lock them in the vault every time. I’d tell them ‘I’m not gonna lock the door with the tumblers, I’m only going to key-lock it’. Then I’d go and change my appearance, and get a taxi to the airport.”

ONCE there, he’d call police and tell them a robbery had been committed and to check the bank he’d just robbed.

“By the time the coppers fooled around outside the bank and did their siege thing and all that bullshit, I’d be on the plane waving out the window as I flew out of Australia,” he says.

The Marco Polo suite at Hong Kong’s Peninsula Hotel is Carl’s favourite haunt when he’s on the lam. It’s opulent and costs $1200 a night. Cashed-up Carl can afford it, though.

“A good haul (from a bank robbery) would be about 30 grand — that’s like 200 grand today, you know,” Carl says.

“You could have bought three or four houses with the money.”

Eventually, the law catches up with him again after his fake passport is detected following a short holiday to Bali.

While he’s awaiting extradition from Hong Kong to Australia, Carl is housed in the notorious Siu Lam hospital, a psychiatric institution that has a lasting impact.

“It had white tiles on the floor, all the walls, on the bloody roof, even. You’d hear people being brought in all the time, then you’d hear the torture starting. They did terrible things there. I spent a month or so in there.”

Back in Parramatta jail, facing another six years behind bars, he cooks up his most elaborate plan yet, a ruse so brazen that it will make front pages around the country and inspire a book and a film. Carl’s about to go blind.

“I was trying to figure out a way to get out of prison, something that no one else had ever done,” Carl says.

“If I went over the wall I’d be on the run again and I really wanted to get out of crime at that stage. I was sitting there thinking and I thought ‘no one’s ever gone blind in jail before’.

“From that day on I started rubbing my eyes, making them red, blinking and bumping into things.”

The prison officers are suspicious, tough, thinking it’s just another one of Carl’s madcap stunts so they call in the doctors — including Australia’s most famous eye specialist, Professor Fred Hollows, who, after several tests, declares that, yes, prisoner Carl Synnerdahl is definitely blind.

“By this time I’d learned how to read Braille, I had a Braille watch and I had a cane,” Carl recalls with a grin.

“But the judge still sentenced a man to six years’ jail who was blind. What sort of human being does that?”

The now legally blind Carl is transferred to the low-security Cessnock jail, in NSW’s Hunter region, where he takes full advantage of his newly-acquired disability, heading out on day leave to various functions and events — and even, he claims, juggling affairs with married women.

Eventually, he says, everything “came undone like a ball of string”.

“In the end, I was in and out of jail on basically a daily basis — going to concerts and events in Newcastle” he says.

“I’d have women come and pick me up from prison and take me to various things.

“That’s where it all unravelled. I fell in love with this lovely lady and I screwed up a lovely family. That’s been eating at me ever since.

“In the end I was the one who got sucker-punched.”

After two years and unable to maintain the sham any longer, Carl decided to do a runner while on day leave. It’s a big story and the media has a field day.

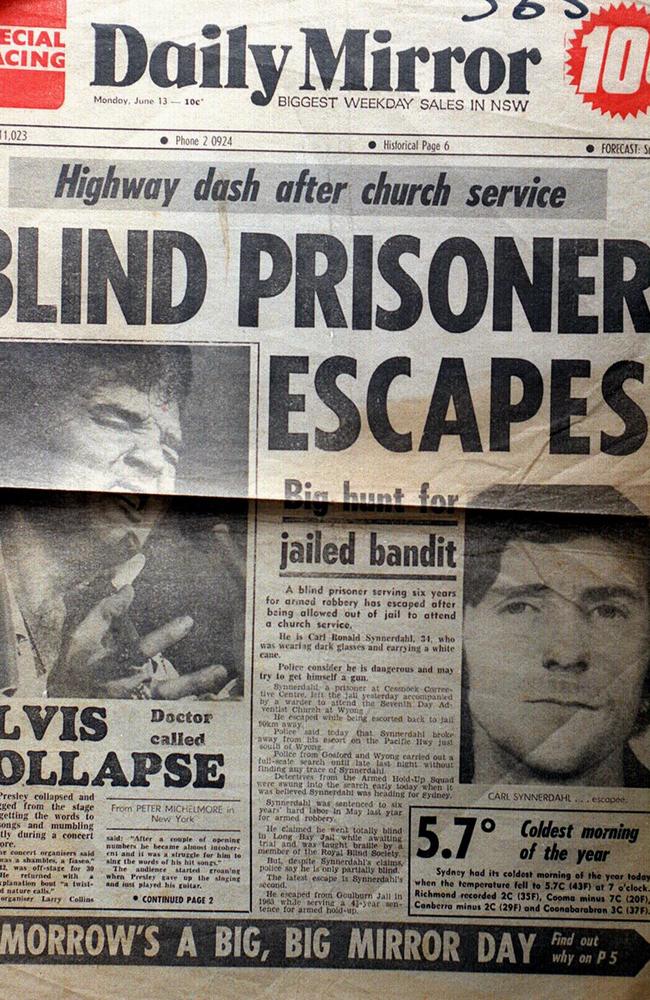

“Blind prisoner escapes”, screams Sydney newspaper the Daily Mirror, splashing Carl’s picture on the front page next to a story about singer Elvis Presley collapsing.

“I took off to Sydney,” he says. “I had a couple of girls — working girls — meet me in Sydney and we lived in a lovely mansion with a swimming pool in North Sydney.

“I was running around Sydney for a few days and I was hooked up again within a week.”

BACK in Parramatta jail once more, Carl starts to write a book. It’s not even finished when producers Errol Sullivan and Pom Oliver are knocking at his cell door, pitching for the film rights.

It’s 1982. Carl is out of prison with his new wife, Alice, a doctor he’s met while she’s working in prison, and he’s about to attempt something that — up until this point — he’s never done before. He’s about to go straight.

Alice is working in a surgery when Carl convinces her that she should buy her own practice. He gets a $14,000 loan from the bank — ironically, one he robbed about a decade before.

Soon they have two surgeries, which they sell for a profit and, after a stint getting out of the rat race in Tasmania, they plough their cash into a surgery in Ballina, on the NSW north coast, and open a 24-hour clinic.

It’s a hit, and Carl and Alice are soon raking in the money.

They buy a house on the beach and luxury cars. Carl has cash and, for the first time, doesn’t have to hide it under his bed.

For practical purposes, the burgeoning medical empire is in Alice’s name — and when things go sour after he meets his current wife Yvonne she changes the locks and Carl finds himself with nothing again. Carl and Yvonne and children Jesse and Leah from his marriage to Alice — just primary school kids at the time — settle in the little town of Uki, in northern NSW, on the bones of their butts.

“We were that hard-up for money I decided to go and get some fruit and vegies from the roadside stalls,” Carl says.

“I never used to touch the money but I stole bananas and tomatoes to make sandwiches for school. This is in 1993. I had two Rolls-Royces, a house on the beach ... I lost the whole lot when she pulled the pin on me.”

Not long after that, Carl and Yvonne pack everything into their beat-up old Mazda Capella and move to South Australia.

They settle in the northern suburbs of Adelaide before moving to a little hamlet in the Barossa Valley.

They’re still there today, living in a humble house with sweeping views over the rolling hills.

They take care of Carl’s granddaughter, and three little terriers complete the picture. He even meets with the local cleric, Pastor Danny Lanthois; a man he describes as his rock, even though he maintains he’s an atheist.

His health’s not good (Carl insists he only smokes “one a day”) and he’s had a femoral bypass, a new heart valve, a stent, a bowel operation and a malignant lump removed in the past few years — but says country life suits him.

“People were bringing hot meals to our home after my chemo; we don’t pay for eggs or anything like that,” he says.

“These people are above and beyond. Everyone here knows my background. I will not go to anyone’s home without them knowing who I was and what I’d done.”

Despite the fact that Carl has now been on the straight and narrow for decades, he says not a day goes by when he’s not haunted by his past.

“My conscience is my worst enemy,” he says.

“There’s not a day goes by that I don’t say, ‘What the f..k was I thinking?’

“That’s why I’ve moved here, to get away from all that. That’s why I call this my community of angels.”

BIZARRE EXPLOITS BECAME A FILM

CARL Synnerdahl doesn’t like the book that he wrote in prison.

It’s hard to tell the truth about the system when you’re still captive within it, Carl argues.

In fact, he dislikes Hoodwink so much he’s been known to buy copies from second-hand bookstores and on eBay just so that other people can’t read them.

The 1981 film version of his story, also called Hoodwink and starring the late John Hargreaves, Judy Davis and a young Geoffrey Rush (pictured), also rates pretty lowly, according to Carl.

“It was a shit movie,” he says. “The guy who played me (Hargreaves) was six foot two for a start, so it didn’t show a small guy who had enough backing to get himself through.

“Claude Whatham, the director, was bought out from England with no knowledge of the Australian way of life or the idiom. All he wanted to do, I found out later, was have naked women in front of the camera! I didn’t even want any sex in the movie, it’s not what it was about.”

Carl is now close to completing a new book — with the working title Code Black — which, he says, tells the real story of his life and pulls no punches.

“I’ve been able to speak much more freely in this one because I’m not inside,” he says. “This is the real story.”