Chimp’s quest to become human

When baby chimpanzee Julius was rejected by his tribe, he found a new family — but can a chimp really fit into human lives?

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For a time, Julius the chimpanzee was the most beloved animal in Norway – a TV celebrity who children couldn’t get enough of.

Born in the Kristiansand Zoo, but rejected by his mother aged just six weeks, Julius was taken in by zoo director Edvard Moseid and his family who handled parenting duties.

The plan was to return the young chimp to his tribe, but Julius was not so keen to leave. And when he was returned, numerous times, he was snubbed. Julius was a misfit, unable to live with his own species, and, eventually too big for his human family, had no place in our world either.

It made riveting television in Norway, prompting his rise to fame.

Eventually Julius was able to find a new tribe, and his place. If that all sounds like an experience many humans could relate to, it is why Julius, now 40 years old, is the subject of his own biography.

In the following extract from Almost Human, by Alfred Fidjestøl, Julius is enjoying playing with – and learning from – Moseid’s daughters Ane and Siv.

But can a chimpanzee really fit into human ways?

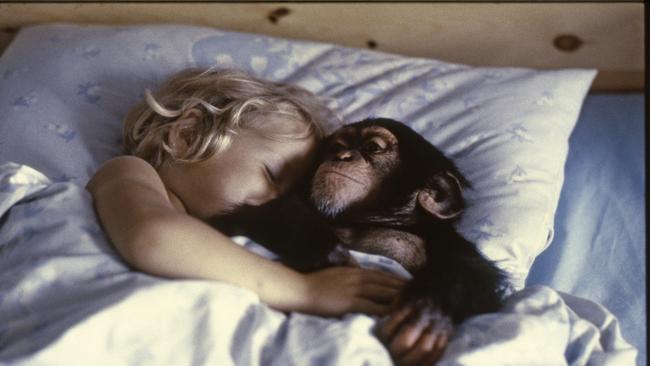

Back at Moseid’s house in Vennesla, Julius was becoming a worthy playmate for the two girls.

He slept at night in a cardboard box, which was sometimes kept in the bathroom and sometimes on the floor of Edvard and Marit Moseid’s bedroom.

As soon as he woke up, however, Julius would dart into the girls’ room to play.

He was physically smaller than his “sisters”, but much more advanced in his motor skills. He climbed the curtains in spite of their efforts to deter him.

In truth, he needed all of the climbing practice he could get in advance of the day when he would be returned to the chimpanzee group.

He enjoyed wrestling and play-fighting, playing tag and racing with Ane and Siv. If they raced, he made absolutely certain no one cheated.

He stood on the start line swaying back and forth while waiting for the start signal. Together with Ane – and only with her – he developed his own game: one of them would sit with a stick or piece of grass sticking out of their mouth while the other tried to grab it with their lips.

If the stick happened to slip out of Julius’s mouth or if he lost the game, he would get very sour-tempered.

The girls also taught him how to draw and paint. He was allowed to lie on their beds for hours on end, though always with the rule that he was not permitted to get used to sleeping in a bed or sitting at a table.

For the girls, mealtimes were heart-wrenching, as Julius, the family’s uncontested centre of attention, would be banned from their company only because it was time to eat.

Sweets were also against the rules for Julius but he was quick to learn the art of flattery.

When the two girls sat on the sofa, watching children’s TV with their snacks, he would squeeze between them, place one arm around each and kiss them on the cheeks, melting their hearts and undoing their parents’ principles. Somehow, a piece of candy would “fall” on to the floor or a third straw would just happen to appear in the bottle of soda.

It was inevitable; Julius began adopting more and more human behaviours each day. He learned to recognise verbal messages such as “time to eat” or “we’re going outside now”. He understood their meaning without difficulty and reacted just like any other child. Unlike other children, however, Julius never gave the impression that he was planning to try speaking up for himself. No single word ever passed his lips.

In 1947, a decisive study was conducted to find out whether it was possible to teach chimpanzees to speak. The psychologist Keith Hayes and his wife, Cathy Hayes, adopted a one-month-old chimpanzee infant named Viki and raised her as a human child with intensive language training. When Viki died at six years of age, she had only learned to say and use four words: “papa”, “mama”, “cup” and “up”.

Later studies determined that due to differences in tongue motor skills, it is impossible for chimpanzees to create many of the sounds required for human speech. In 1966, however, the researcher couple, Allen and Beatrice Gardner, was able to teach the chimp Washoe, who lived with them, to communicate using several gestures taken from ASL, or American Sign Language.

By the time Washoe left the couple in 1970 to become a part of Roger Fouts’s research at the Institute for Primate Studies in Oklahoma, she had mastered 130 different signs.

The experiment was hugely significant, suddenly allowing for a relatively advanced method of communication between humans and chimpanzees.

Washoe was observed teaching the signs to an adopted chimpanzee son.

The following year, inspired by the Gardners’ breakthrough, several other chimpanzees were taught ASL. Research with these chimps showed that they were able to group differing objects under the same concept, for example grouping various types of dogs under the term “dog” and various insects under the term “insect”.

They could transfer signs that they had learned correctly in one context into other contexts. For instance, Washoe had learned the sign for “to open” in the context of a door, but could apply it herself to other situations, such as when she wished to open a crate.

And chimps were able to combine different signs into meaningful combinations.

Washoe signed the gestures for “water” and “bird” when she saw a swan for the first time. Another chimpanzee combined the signs for “cry” and “fruit” when explaining the concept of an onion.

Although these experiments were well known by the time Julius was born, and though it was apparent that he was able to comprehend quite a lot, there was no point in teaching him sign language communication. On the contrary, the goal for Julius was that he would come to understand and remember that he was a chimpanzee and not a human.

Of course, psychologically and commercially it may have been an intriguing idea to raise him the opposite way in order to see just how human-like he could possibly become. Such experiments had been carried out many times in the past. In 1931, the renowned American psychologist Winthrop Niles Kellogg adopted Gua, a seven-month-old chimpanzee, and raised him together with his own 10-month-old son, Donald – in principle providing both youngsters with an identical upbringing.

The experiment was called off after only nine months due to Kellogg’s disappointment over the chimp’s lack of verbal development, but also because he and his wife had begun to realise the danger and unpredictability of certain situations for their human son.

A more stalwart couple, Jane and Maurice Termerlin, raised the female chimpanzee Lucy in their home from 1964 until 1976, from the time the chimp was a single day old until she reached the age of 12.

She slept in a crib at their bedside, was fed human formula from a bottle and received care and bodily contact around the clock.

At the age of one, she ate meals with the couple at the table, using silverware and a glass just like a human.

She often accompanied her mother to work.

She never got used to using the toilet, however, nor did she develop the taboo relationship that most humans have to their own faeces. At the age of three, she was so difficult to have in the house that the couple was forced to create a separate room for her where she could play without destroying things while unattended. Still, the Termerlins continued their human child rearing. Lucy learned how to dress herself, though she preferred to dress up in other people’s clothes rather than her own. She also learned to handle a range of instruments and appliances, from keys and pencils to vacuum cleaners and lighters. She was trained in ASL, and the Termerlins were able to communicate with her in a meaningful way.

Lucy loved leafing through newspapers with her own cup of coffee, alongside her parents in the morning. Her coffee was, of course, nothing but warm milk mixed with a teaspoon of coffee to give it colour. At only three years of age, she tasted her first sip of alcohol when, by chance, she suddenly grabbed a whiskey glass from a guest who was visiting and chugged it down. When they later discovered Lucy’s penchant for boozing in the garden with rotten apples, her liberal foster parents decided it was time to allow her an indulgent drink every now and then. She was thereafter permitted to have a drink or two before dinner, a gin and tonic in the summer and a whiskey sour or Jack Daniels with 7-Up in the winter. Lucy relished those evenings curled up on the sofa with her parents, sipping her drink and flipping through magazines before dinnertime.

When she reached puberty, they gave her a copy of Playgirl, which she seemed to enjoy very much. She taught herself to masturbate shamelessly, quite creatively, with the family vacuum cleaner.

For 12 years Lucy lived like this, but thereafter, things were no longer manageable. It became impossible to have her in the house. Although the chimpanzee is a human’s closest genetic relative, it is nonetheless an animal we have never been able to fully tame. Even a chimpanzee hand-raised among humans with familiar, close and emotional bonds will, at some point in time, transform from a tame and predictable animal to a dangerous one.

To tame an animal, the species must be systematically bred with particular care to their unique abilities.

Modern animal keepers … haven’t yet reached the conclusive ability of taming them.

The Termerlins had put themselves – and Lucy – into an impossible bind. Maurice Termerlin was a psychology professor and the adoption had been part of a larger research project led by the psychologist Bill Lemmon, in which different types of animals were raised among humans. But the experiment was poorly thought out, morally dubious and completely lacking in a long-term plan for … Lucy’s life.

The couple didn’t want to euthanase her or send her to a zoo or research laboratory, and so the 12-year-old chimpanzee accompanied researcher Janis Carter to a rehabilitation centre for chimpanzees in the Gambia.

Carter hoped to persuade Lucy to adapt to a life in the wild.

But Lucy was incapable of interacting with other chimpanzees, for example, only becoming sexually aroused by humans.

She displayed many of the classic signs of depression, refused to eat for long periods and constantly signed the ASL sign for “pain”.

After many years of training and acclimation, she was nevertheless set free into the wild. Her skeleton was found two years later, missing its hands and with its head torn off from the rest of the body.

Julius was going to avoid this fate.

He was not ever going to sit sipping a gin and tonic with a newspaper in one hand. He was to understand, at all times, his place as a chimpanzee. He was going to be returned to his community.

Extract from Almost Human, by Alfred Fidjestøl, published by Hachette Australia, $32.99, available Tuesday