FOR civilians in the Territory in World War II, it was a time of unrelenting hardship and tough work. For some, it brought trauma that affected the rest of their lives. For others, it brought death and destruction. But through all of it, their resilience shone through to the sunlit days of peace after 1945.

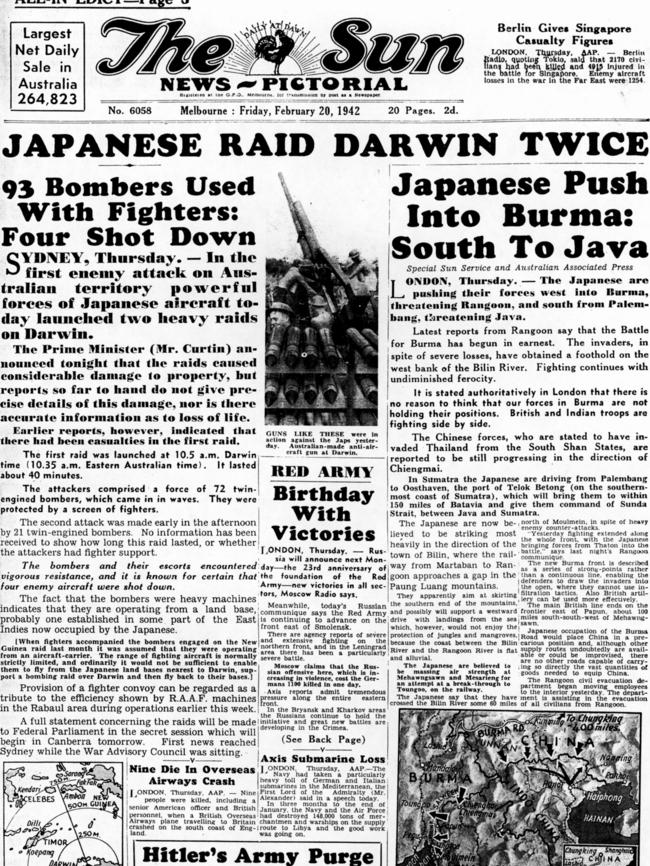

The war had been with Australia since 1939. In 1941, the possibility of conflict for the Allies with Japan loomed ever larger. In early December, the Japanese Navy attacked the United States’ base of Pearl Harbor and its outpost in the Philippines. Australia was deeply alarmed. With the majority of its troops in the European theatre fighting against Germany and Italy, its small population of seven million was stretched to the limit.

Evacuation

A FEW days after Pearl Harbor was attacked, the federal government issued an evacuation order for Darwin. It required all women and children to compulsorily leave the town with no more than “35 pounds” of luggage — about 16kg. The order, circulated widely, assured everyone that the federal government had made arrangements for “the comfort and welfare of your families in the south”.

That would be found to be far from the truth. Many of Darwin’s women did not want to go. Journalist Douglas Lockwood’s wife got around the order by becoming one of those who remained for “essential services” — she managed to get taken on as a typist for the Army.

Several women remained on as staff at the town post office. But for most it meant a speedy evacuation, by force if necessary, with groups assembling on the wharf to board coastal steamers. Wendy James, still living in Darwin, remembers: “Protests were useless, so our angry and stressed mother hurried us down the wharf to the waiting ship with a string bag each and the baby in the pusher.”

The journey south was itself full of tension. Japanese and German submarines were prowling the coastal waters of Australia — indeed, one was sunk off Darwin in January of the new year — and passengers routinely had to take turns on the weather deck spotting for their periscopes.

Protests were useless, so our angry and stressed mother hurried us down the wharf. — Wendy James

The ships were overcrowded, under-provisioned and slow. Conditions in the southern cities were much worse than expected, as evacuee Joy Davis recalled: “The evacuees received no help from the general public in the south, as you would normally expect, because the evacuation of Darwin was not publicised and the general public were not aware of it.

“There were no comforts nor accommodation. We were on our own; many of us had no money, and certainly no warm clothes or anything else needed to make a home. No utensils, linen, furniture et cetera, all we had was one suitcase of summer clothes for the whole family.”

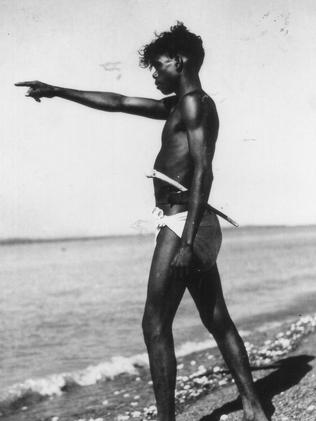

The local Aboriginal population was rounded up and moved well south of the capital. By March 1942 there was a population of around 2000 Aborigines in camps at Koolpinyah, Adelaide River, Pine Creek, Katherine and Mataranka. Those on the Tiwi Islands stayed on until a later evacuation moved the women and children out. The men who remained would be in the flight path of the raids which were to come over the next two years. Many Aborigines in coastal villages were recruited to several quasi-military operations such as the Coastwatchers.

Life in Darwin

Back in Darwin, enemy air raids were expected. Slit trenches and air raid shelters were being built everywhere. The number of civilians had dropped to around 2000 when the first bombers appeared.

There were over 10,000 military men replacing those who had departed by then, and together they endured the terrifying attack on February 19 that killed 235 of the town’s residents.

Among them were many civilians. The entire post office staff was lost, most of them women, including three members of the family of Hurtle Bald, the Postmaster. Rows of graves lined Mindil Beach, and many of the civilian survivors fled south. The Territory was transformed everywhere by the war. Survivor Wendy Farrell remembers: “There were army tents everywhere in the Alice Springs hospital grounds.”

Slit trenches were common even in the inner towns far from the sea. Residents everywhere lived in fear of invasion. Everyone’s life was oriented to the war. In Elliot, for example, a platoon of soldiers was stationed in the camp set up at No. 8 Bore. The fruit and vegetable garden there was huge, and the camp could house 1500 troops.

Development of infrastructure

The overland supply route became increasingly important. This essential link ran convoys of trucks north from the railhead at Alice Springs to the southern railhead of the North Australia Railway at Larrimah. American forces, and even British and Dutch military men, moved into the Territory by the thousand. Airfields sprung up everywhere — by the end of the war there were 56.

All of this increased military presence meant more support was required, and the civilian numbers present rose accordingly. The Stuart Highway, originally just a very bad dirt road, was improved and part-sealed; the acquisition of modern road-making units from the US eventually saw 22-30km a week being finished. By mid-December 1943 the entire highway was sealed.

The demand for labour

Each of these staging camps created a demand for labour, including for tasks such as cooking, washing, cleaning and vehicle maintenance. On average some 700 Aboriginal men and 50 Aboriginal women were required at these camps during the war.

Allowing for replacements and rotations, most likely well over 1000 Aboriginal men and women served in this capacity. Without this labour, the army would have struggled to maintain this vital supply line.

The Aboriginal workers were paid five shillings per week, about $50-$100 in today’s money, and were provided with rations, clothing and accommodation. Most importantly, the army also provided for the “aged and unemployable”. This mostly included women and children and meant that family groups were able to stay together.

To provide meat for Allied soldiers the Army established its own slaughter yards, cooling chambers and delivery system about 65km north of Katherine. Butchers from the Army resumed civil occupation, on Army pay, and Aboriginal labour was used to bring the cattle into the slaughter yards from widely dispersed areas.

Coming back to Darwin

For Australia’s front line, World War II was a tremendous blow. Many civilians returned after the Japanese surrender and found Darwin a town devastated by the two years of air raids. Many never made it back, too traumatised by the thought of starting again.

‘Astounding’ WWII site loses heritage listing amid Top End housing push

Just 24 hours after laying a wreath for Anzac Day commemorations, the NT Planning Minister publicly announced he would remove protections from historic WWII wreckage in an area slated for a 4000-home development.

‘Lest we forget’: Bombing of Darwin war hero dies aged 104

World War II veteran and Bombing of Darwin survivor Brian Winspear AM has died peacefully aged 104.