‘Apocalyptic’ Ebola and childhood pandemic tragedy: The untold heartbreak that haunts Qld CHO

The man steering Queensland into a new life where we ‘live with Covid’ has had a life shaped by infectious diseases, which started with a family tragedy when he was just six years old.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If Dr John Gerrard can cobble together a spare hour or two, there’s a storage shed in suburban Gold Coast where he likes to go. He rolls up the garage door, enters his man cave and surrenders to a childlike fascination with model aeroplanes.

It’s the array of skills required that hooked him: the artistry of making the planes, the fiddly electronics and the physical skill of controlling them in flight.

“That’s the bit I’m worst at,” he says, admitting to crashing “an awful lot of planes” since taking up the hobby five years ago. “I’m terrible at it but I really love it.”

Part of the appeal, Gerrard says, is that he’s not at the top of the pecking order in his model aeroplane club. In fact, he’s “way down the bottom”.

“It’s good for you to be disempowered from time to time in different ways,” he says. “It makes you understand different people’s perspectives.”

Everyone has a perspective on how Gerrard should do his job as Chief Health Officer but that’s a role, way up on the Queensland Health ladder, in which his skills are well honed.

After decades of training and experience in infectious diseases, he’s the navigator guiding the state through the Covid-19 opening up phase.

Gerrard admires the work of his predecessor, now Governor, Dr Jeannette Young, but says he’ll do the job differently. Because the job now is different.

“The job in her time was suppression and vaccination,” Gerrard says.

“The job of vaccination continues but now it’s about the cautious relaxation of measures over a period of time and monitoring them.”

It makes for a stark juxtaposition: Young, by and large, gave us good news – cases controlled, short lockdowns released. Gerrard is prescribing a bitter pill. If our largely vaccinated populace wants to reunite and “live with Covid”, we need to accept infections at a manageable level.

Cases are multiplying into tens of thousands. It is, he says, an inevitable and necessary step to moving from a pandemic to endemic phase of the virus.

This is Gerrard’s biggest challenge in a career filled with milestones.

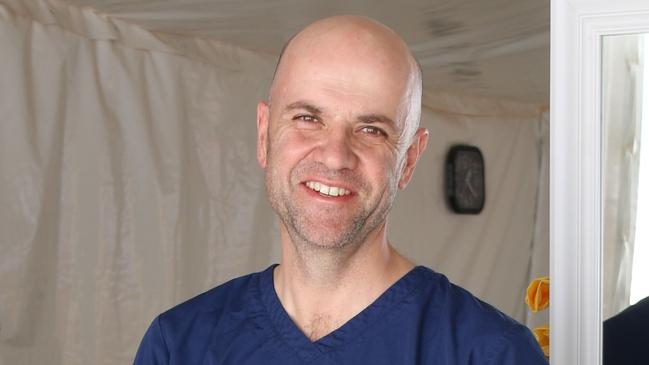

The former Gold Coast University Hospital director of infectious diseases was the first Queensland doctor to treat patients with Covid-19, travelled to Japan to help out with the diagnosis and care of crew on-board the virus-filled Diamond Princess cruise ship, and to Africa during an “apocalyptic” ebola outbreak. He’s even had a worm named after him.

He’s a far more affable man in person than at press conferences where his often unvarnished statements and bald head, sometimes capped with a rakish Panama hat, evoke a comic book villain.

His passion for his work is obvious. Get Gerrard talking about pandemics and he will riff about the various strains throughout different outbreaks, how viruses undergo dramatic “shifts” every few decades or so that can cause pandemics, and less dramatic “drifts” in intervening years.

He’ll explain that the influenza we experience today is based, predominantly, on the last big antigenic shift of the influenza virus in the 1968 Hong Kong flu pandemic.

Gerrard knows this very well. It killed his brother.

Eleven-year-old Stephen Gerrard died of H3N2 influenza, within hours, at home, without seeing a doctor. He’d got sick on a school excursion as the 1968 pandemic ripped through NSW.

Gerrard was six. Words and images from that time remain clear but he won’t share them. “They’re just too horrible,” he says.

Now, at the age of 60, Gerrard is dealing with a different pandemic but viruses do coexist. While Covid-19 is his focus, influenza this winter has Gerrard on alert.

For two years, influenza has been largely absent due to international border closures. Now they’re opening and our immunity will have waned.

“There is significant risk,” Gerrard says, “that there will be a significant influenza epidemic.” Covid will still be circulating. “It’s likely to be a double whammy.”

BIG CAREER

Life choices have many influences and Gerrard is a man for whom analysis and reason are too important to give way to sloppy thinking. He dismisses the idea that as a boy, witnessing the shocking death of his clever, sporty brother set him on an unyielding path to becoming an infectious diseases doctor.

“It doesn’t work like that,” says Gerrard, whose other brother Peter, 61, is a software engineer in Sydney.

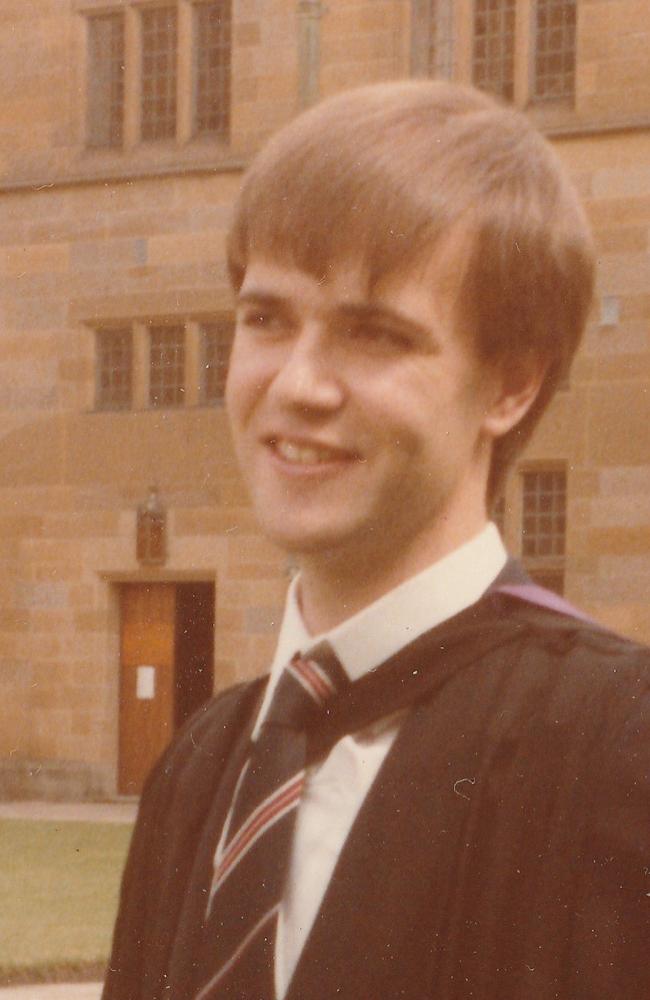

Gerrard was a bright lad and medicine called. He went to the University of Sydney, sharing classes and tutorials with Young, who he says has not changed a bit.

“She was that girl in the tutorial group who always knew where the next class was,” he says.

When it came to deciding on a specialty, Gerrard was torn between intensive care and infectious diseases.

Ultimately, infectious diseases won out because of its diversity, the way it combines laboratory work and human contact – and the fact there’s always something new on the horizon for medicine and science to overcome.

He recalls that when he first came to work at the Gold Coast in 1994 there were two major infections: HIV/AIDS and hospital-acquired MRSA, or methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus, commonly called golden staph. Back then, those two infections represented about 90 per cent of his work.

“There were wards full of AIDS patients,” he says. “That’s gone.”

Today, HIV is controlled with medication and the heartbreaking decline into AIDS and death has been drastically reduced.

MRSA in hospitals was a scourge until one simple measure was introduced: alcohol-based hand rub.

“I don’t know if people know that,” he says.

“Such a little thing has made an enormous difference in hospitals; it’s saved countless lives.”

It was an AIDS case that first thrust Gerrard into the national and international spotlight on returning to Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1993 after post-graduate training in London.

A research project took him deep into decades-old paper records where he found a case of a single, 72-year-old man from Sydney who died in September 1981 of pneumocystis pneumonia, a fungal infection common in AIDS patients. But Australia’s first recorded case of AIDS was in late 1982.

Gerrard located the man’s preserved lymph gland tissue and recovered the DNA, then had it tested for HIV. It was positive.

“It was textbook, classical AIDS,” says Gerrard.

“It just wasn’t in the textbooks.” The finding rewrote Australia’s history of HIV/AIDS.

His relocation to the Gold Coast with wife Anthea the next year answered a long-held desire to move to Queensland, sparked by a visit during Expo 88.

It wasn’t late night chicken dancing at the German beer hall that seduced him, he says, but the state. “It was obvious this was the future of Australia,” he says.

“It just had a sense of freedom and possibility that didn’t exist in Sydney.”

The CHO job means a move to Brisbane and he’ll miss cycling around the Glitter Strip with Anthea, 58, a lecturer in law at Bond University.

The couple raised their two daughters on the Gold Coast – Catherine, 22, who is an aeromechanical engineer with the army now based in Darwin, and Alexandra, 21, who is studying arts/law at the University of Sydney.

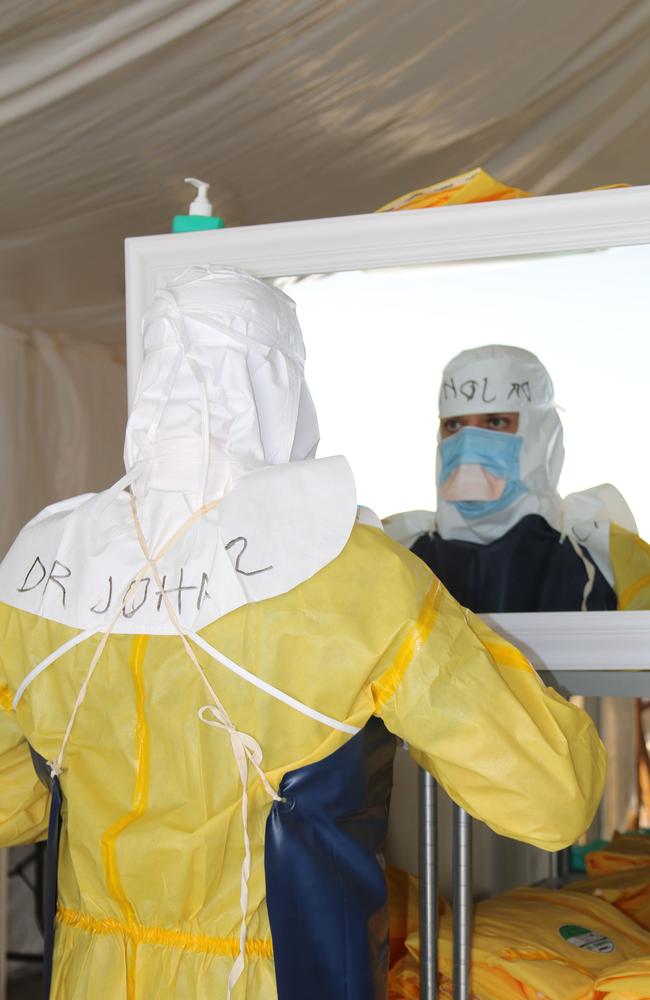

Those girls were front of mind when, as part of an Australian contingent of medicos, Gerrard walked into what he calls an “apocalyptic vision” – the city of Freetown in West Africa’s Sierra Leone in the middle of the ebola outbreak of 2014.

Gerrard says that, as a doctor, you learn to disconnect emotionally from patients “but sometimes you find somebody that you relate to, that triggers you”.

All around him were patients with vomiting, bleeding and diarrhoea but one patient cut through his protective armour – a 14-year-old girl, roughly the same age as his daughters at the time.

The girl’s mother had died of the cruel, haemorrhagic fever in the bed next to her at home. Her grandmother died next to her at the treatment centre.

The girl was desperately sick and sad and would cry and cry. “She tried to escape on Christmas Day and they had to bring her back,” Gerrard says.

She lived, the 50/50 chance of surviving ebola falling her way. But every morning, Gerrard would suit up and walk into the red zone to find more dead.

“Sometimes, they’d come in, lie down on the bed and they’d never get up,” he says. “They’d just be dead when you found them in the morning.”

His first task each day was to identify the dead, then, with others, double bag the bodies and take them to a makeshift morgue.

There was no vaccine for ebola and no real treatment. “We fed them, gave them fluids,” he says. “They had this extraordinary stare; they call it the ebola stare. I think it was fatigue, they could barely walk.”

His face is heavy with the memory. He was, understandably, fearful for his own life. Almost all the staff in another facility in the region were “wiped out”. The last part of his three-day training program before flying to Sierra Leone was the writing of his will.

“It was as scary as hell,” he says.

It remains, Gerrard says, the most emotionally intense and complex experience of his life.

The diversity of life as a keen and curious infectious diseases doctor is illustrated by one of Gerrard’s other claims to fame.

He’s the only living Australian with a human pathogen named after him – the glow-in-the-dark heterorhabditis gerrardi.

The just-visible worm, which burrows into skin, had been elusive to science before Gerrard went hunting in 2009. The bacterium it carries, which causes high fevers and big, red nodules on the body, had been isolated by the US’s Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But not the worm, which was believed to live in warm, wet climates. So Gerrard headed over the border to Kingscliff to see if he could find it.

He talks excitedly of his unusual eureka moment, even offering instructions on how to turn worm-hunter.

“Get those little Chinese takeaway containers, add some soil, a little bit of water to make it just a little damp, then add insects or insect larvae. Cover it over, wait seven days and if your insect larvae are glowing in the dark and dead, you’ve trapped the worm.”

It will take a nematode specialist to confirm the finding but the worm has some interesting telltales. “It has, I think, two penises and eight testicles,” Gerrard says, grinning.

Perhaps a more substantial contribution to medicine was Gerrard’s push to establish the Gold Coast University Hospital. The hospital he arrived at in 1994 was “okay but it wasn’t brilliant”.

It was under-resourced, with most staff from interstate or overseas, so Gerrard and colleagues lobbied for a medical school and university teaching hospital. It opened in 2013. “It was a complete change; suddenly we were training our own doctors,” he says.

The hospital contains an isolation unit designed to cope with airborne infectious diseases. Gerrard pushed for it after seeing infections spread through hospitals in Toronto, Canada, during the 2003 outbreak of SARS, the precursor to SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19. Pre-Covid, it was rarely used.

“There were many times when I turned to my colleagues and said, ‘God, we really did waste a lot of money on this dedicated isolation unit, I feel really embarrassed about this … it’s going to be the biggest white elephant, I just want to bury my head’,” says Gerrard.

“And then Covid came along.”

At first, it was just one Chinese male who presented to emergency with symptoms on January 28, 2020.

But when Gerrard learned the man was part of a tour group from Wuhan, he decided, in consultation with Young, to isolate the entire group of nine. Just three weeks earlier, the World Health Organisation had alerted the world about an unknown coronavirus circulating in the Chinese city.

But the virus wasn’t unknown to the tourists. They knew. They knew the horror unfolding back home. They weren’t angry about their tour being stopped, not belligerent. They were scared.

By midnight, the group was admitted but there was one hitch: Gerrard doesn’t speak Mandarin. A search went out across the hospital to find a stopgap translator. “I managed to find a beautiful nurse on the kidney ward who was Chinese, who spoke Mandarin and English,” says Gerrard. “She saved us.”

As the nurse determined how they were feeling, it became clear the man was not the only one who was sick. Several were.

In the end, five adults and one child contracted the virus, one of them quite ill with a stubborn fever. They all recovered. Queensland had recorded its first cases of Covid-19 and Gerrard helped avert wider spread.

STAR POWER

Not long after Gerrard cared for the Wuhan tour group, he took a call from Screen Australia. The Gold Coast was buzzing with news of Covid-19 arriving in the tourist town and a movie crew was keen to have its anxieties eased.

He agreed to meet, turned up at 5pm, and waited. Then the phone rang. They were delayed an hour. He agreed to wait but come 6pm, he took another call. They’d be another hour. “I said, ‘This is asking a bit much but okay, I’ll do it’.”

Finally, Gerrard was ushered into a mini-theatre and waited for “the crew” to arrive.

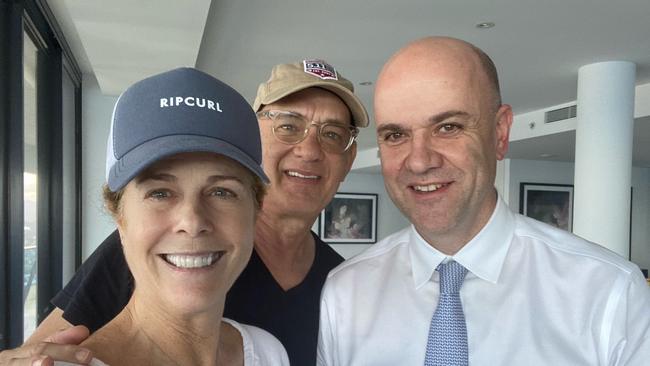

“They come in and I’m standing there and I thought, ‘That’s Tom Hanks!’,” recalls Gerrard.

He was right; the megastar was on the Gold Coast filming an Elvis biopic and was now settling down to listen to Gerrard talk about this emerging virus. Right behind him was actor Maggie Gyllenhaal and the “oh my god, he’s a charmer” young star, Austin Butler.

It wouldn’t be Gerrard’s last brush with Hanks.

On March 11 that year, they met again: in the Gold Coast University Hospital, as the actor and his wife, Rita Wilson, battled Covid-19.

It struck Hanks with crippling body aches, fatigue and poor concentration, while Wilson lost her sense of smell and taste, had nausea and a high fever.

That’s from Hanks’s description: Gerrard will not be drawn on their illness but says they were good patients.

He’d seen quite a bit of Covid-19 by the time he was tending to the celebrity couple, having flown to Japan in February to help with the task of disembarking and diagnosing the 2666 passengers and 1045 crew of the Diamond Princess.

The cruise ship had arrived in the port city of Yokohama with Covid-19 cases that multiplied as passengers remained on the ship.

“They just locked these people on the ship and, of course, the virus just kept spreading and spreading,” Gerrard says.

“No one knew what to do. The ship wouldn’t leave and the Japanese wouldn’t let them off.”

After more than two weeks, passengers were disembarked and then the crew. Gerrard’s job was to care for the crew, housed in one tower of a giant complex normally used to train and accommodate tax officers.

It had its challenges; a senior crew member had grown fondly acquainted with the ship’s bar and cultural differences made for prolonged negotiations with bureaucrats.

But Gerrard learned a great deal about the virus. In the end, about 700 people contracted Covid-19, with 30 people on ventilators and eight deaths.

“This was still very early in the pandemic and we were all saying, ‘The rest of the world doesn’t know how bad this is, this is really infectious and it’s killing people’,” Gerrard says. The number of people who required ventilation came as a shock to Gerrard, as did the way the virus targeted older people.

“What I think people don’t understand is it’s got nothing to do with being unfit,” he says. “It’s a specific correlation with age and it’s the changes in the way your immune system functions.”

Another mission called in April last year, with Gerrard flying to the former Dutch Antilles in the Caribbean during the islands’ second Covid-19 wave, just before the advent of Delta. People had been dying daily but Gerrard arrived after the over-60s were vaccinated. He witnessed, again, the power of immunisation.

“It was amazing to see how when the vaccine was rolled out, the virus just melted away,” he says. Gerrard treated younger, unvaccinated people.

He ponders what it would be like if those who are vaccine hesitant, or anti-vaxxers, were able to see what he has seen.

“When there are people dying every day in hospital, unless you’re in the hospital, you don’t see it,” he says. “It’s very abstract to most people … we don’t have carts with bells anymore.”

Much has changed worldwide in those nine months. Delta swept across the globe, now Omicron. Gerrard’s role is turning out to be vastly different to when he signed on in November last year, back when Omicron was yet to land in Australia and Queensland’s border reopening was already scheduled.

As cases rise to record levels, Omicron is sending shivers through the community but he maintains the border opening was the right thing to do. He continues to look internationally and nationally for data and trends and tweak Queensland’s settings accordingly, such as recommending masks and working from home when the Omicron surge began to bite.

His eyes remain firmly on intensive care admissions and hospitalisations. They’re the figures that count, he says.

He’s braced himself for criticism, knowing that his decisions will have deep, negative impacts on many.

He admits that the media and public’s interpretation of his advice “does concern me”. “You can say one line on one occasion a certain way and it will keep coming back at you,” he says.

An example: Young’s controversial statement in June last year, as Delta was surging in Sydney, that she did not want people under 40 getting the AstraZeneca vaccine.

He insists the context was important: there was no virus circulating in Queensland at the time and ATAGI (Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation) had not recommended AZ for under-40s, despite the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, giving the younger age groups the go-ahead.

“In the context of the time (Young’s advice) was perfectly reasonable and appropriate,” Gerrard says.

Gerrard has until April before the CHO’s Covid-19 emergency powers expire and he’s careful to be clear about the process of extending them. He can put his case to the government but it’s not his decision. “It is up to the parliament,” he says.

“If they say no, it doesn’t happen.”

He’s swatted up on legislation governing the role – with help from lawyer Anthea. “I was given the abridged, sort of dummies version, of the Public Health Act for non-lawyers, which I read dutifully and she said, ‘Oh no, you need the whole Act’. So she printed out the entire Public Health Act and went through it with me.”

The couple has accepted that Gerrard will be working long hours in the Covid-19 battle. Young suggested recently that her “terrifying” hours as CHO could have been one of the reasons her original replacement, Dr Krispin Hajkowicz, who has young children, decided not to take the job.

For Gerrard, the timing was right. Covid-19 and its variants will be his sole focus, the culmination of years of experience in the field.

He reveals that, after Young left, all other elements of the CHO job were devolved to others. “The other roles of the CHO are too important and they can’t just forever be playing second fiddle to Covid,” he says.

“This Covid is going to go on for some time yet.”

This virus that has caused so much anguish and loss is unlikely to be eradicated, Gerrard says, but should become milder with each wave. That’s the natural pattern of these things, he says. “Every time the virus mutates, it’s not going to be another pandemic,” he says.

“If it does, that would be extraordinary, never before seen.”

Gerrard will have a front-row seat. He’s earmarked the next two years to wrestling this virus into something manageable, something we can truly live with. His model aeroplanes may gather a bit of dust.

But for someone who, at the age of six, was confronted by the heartbreak a pandemic can inflict, it’s a sacrifice and a challenge he wants.

“In years to come,” Gerrard says, “I can sit back and sip cocktails and decide whether I did a good job or not.”

More Coverage

The smart way to keep up to date with your Courier-Mail news

Originally published as ‘Apocalyptic’ Ebola and childhood pandemic tragedy: The untold heartbreak that haunts Qld CHO