‘Major safety concern’: Fresh EV battery warning following string of fatal fires

There are fresh warnings about the safety of EVs following fatal fires sparked by Elon Musk’s much-hyped Tesla Cybertruck.

On the Road

Don't miss out on the headlines from On the Road. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Fatal fires sparked by Elon Musk’s much-hyped Tesla Cybertruck have put the safety of lithium-ion batteries back in the spotlight.

In August, a Cybertruck struck a concrete barrier and burst into flames near Houston, Texas. The driver was incinerated by the intense blaze.

In November, another Cybertruck went off the road and into a tree in Piedmont, California. It exploded, killing three young passengers and critically burning a fourth.

The US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) has issued six recalls for Cybertrucks, the third most popular electric vehicle in the US, during the past 11 months. Four further investigations are underway into the vehicle’s design safety and full self-driving (FSD) software.

However, Tesla’s Cybertruck isn’t the only electric vehicle (EV) that has experienced this problem.

As more EVs hit the road worldwide, more fires are being recorded.

New York’s fire department responded to more than 200 fires caused by small personal vehicles in the past year. It added that lithium-ion battery explosions (of all sizes) are now the city’s third largest cause of fire.

And when Hurricane Helene swept across Florida in September, it exposed another serious issue. Some 11 EVs and 48 lithium-ion battery-powered devices caught fire after being flooded with salty water.

But transport experts insist it is the novelty of a new technology that is drawing attention.

Accident investigation statistics reveal electric cars are far less likely to burn than petrol-powered cars. The chances of a normal lithium-ion cell experiencing a cascading sequence of heat-releasing chemical reactions is less than one in 10 million.

But the risk increases dramatically if it is stressed by incorrect charging, extreme temperatures or physical damage. And that can lead to intense and long-lasting fires fuelled by the battery itself. Or an explosion.

“When a lithium-ion battery pack bursts into flames, it releases toxic fumes, burns violently and is extremely hard to put out,” explains University of South Carolina Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Xinyu Huang.

“Frequently, firefighters’ only option is to let it burn out by itself.”

Chain reaction

“They can provide a lot of power to our cell phones and to our computers for a relatively long period of time in a very small volume,” says University of Maryland Professor Michael Pecht.

“But because we have so much energy packed in that small volume, if there is a problem, then they’re very flammable.”

Airlines initially banned lithium-ion battery devices when they began to hit the market more than two decades ago. But design and manufacturing improvements have since made everything from mobile phones to wireless earbuds part of everyday life.

Any form of stored energy is potentially dangerous.

And vehicle batteries contain far more energy than a mobile phone.

The ability of petrol to vaporise into a highly flammable gas makes it so appealing for use in a combustion engine. But those same fumes are explosive if released into a confined space.

Likewise, standard lead-acid batteries can expel hydrogen and oxygen when damaged. If ignited, this produces an intense flame.

Lithium-ion batteries pack more energy into less space than their older cousins. So their explosive potential is greater.

But the design of modern battery packs often involves hundreds or thousands of individual lithium-ion battery cells chained together. When one is damaged, it can gradually overheat. That, in turn, causes its neighbours to overheat – and so on.

This “thermal runaway” effect can trigger fires and explosions within moments. Or months.

The fiery demise of a Chevrolet Volt after a routine US crash test experiment in 2011 drew international headlines. It had taken three weeks before the damaged battery collapsed to ignition point.

Built-in Battery Management Systems now monitor most car batteries in real time. The automatic systems can both warn of impending failure and take steps to reduce the risk.

“However, as the range and performance of EVs improves, their batteries are getting bigger, making fire safety a serious challenge, especially in indoor environments,” argue University of Navarra researchers César Martín-Gómez and Mohd Zahirasri Bin Mohd Tohir.

In an essay published by The Conversation, the Spanish academics say their recent research points to the material used in the cathode (the electron through which a current leaves a battery) of lithium-ion batteries as the primary source of failures.

Some use lithium iron phosphate (LFP).

But most use nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC).

“While preferred by manufacturers for lower production costs, (NMC) batteries are more prone to thermal runaway, making them a major safety concern,” they conclude.

Damage control

Firefighters globally are warned to avoid using most traditional methods when confronted by an EV fire. Water can react violently with exposed lithium. Foam cannot handle the intense heat. And powder extinguishers have no cooling effect on the battery and cannot coat vertical surfaces.

But new Aqueous Vermiculite Dispersion (AVD) mists can both cool a battery cell and smother it in a heat-proof barrier.

Nevertheless, Tesla insists petrol-powered cars are 11 times more likely to catch alight than one of its EVs. It argues that battery vehicles have recorded only one fire for every 330 million kilometres travelled.

But experience continues to expose some unexpected threats.

Flooding from Hurricane Helene reportedly caused dozens of EVs, golf carts, mobile wheelchairs and scooters to catch fire. Florida State Fire Marshall Jimmy Patronis warned their batteries were “ticking time bombs” as many did not ignite until after they had been recovered.

“According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, about 36 EVs flooded by Hurricane Ian in Florida in 2022 caught fire, including several that were being towed after the storm on flatbed trailers,” notes Associate Professor Huang.

The problem, he adds, is that floodwater – particularly if it is salty – can be conductive.

“Pure water is not very conductive, but the electrical conductivity of seawater can be more than a thousand times higher than that of fresh water,” Huang explains.

If it leaks into a battery pack, it can bridge the anode (-) and cathode (+) terminals.

“The battery can short-circuit, inducing rapid corrosion and electric arcing, and generating excessive current and heat,” he adds.

“Rapid corrosion reactions within the battery pack produce hydrogen and oxygen, corroding away materials from metallic terminals on the positive side of the battery and depositing them onto the negative side. Even after the water drains away, these deposited materials can form solid shorting bridges that remain inside the battery pack, causing a delayed thermal runaway. A fire can start days after the battery is flooded.”

What can be done?

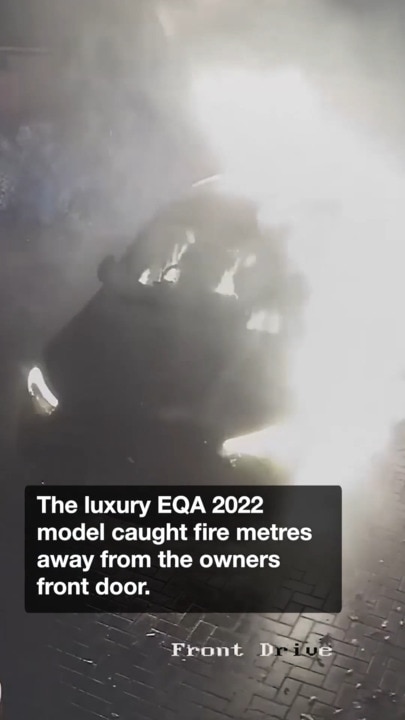

Earlier this year, an unplugged Mercedes-Benz exploded, destroying an underground car park near Seoul, South Korea. The fire ruined a high-rise apartment block and took eight hours to extinguish.

EV sales have since plummeted in the country. And the national government launched an extensive overhaul of safety policies.

New regulations compel device manufacturers to reveal everything about the batteries used in their products. New safety testing standards have been imposed. A new quality-control certification process is being initiated. And no lithium-ion battery is allowed to be fully charged to its maximum potential.

This is in line with the University of Navarra’s findings.

“From 0 per cent to 75 per cent charge, fire intensity remained stable, but at full charge, fire strength surged,” the authors state.

“This increase aligns with real-world incidents, as many fires occur during vehicle charging.”

Ultimately, though, this relatively new technology needs further research and testing.

“Lithium-ion technology is still relatively new,” says US Sandia National Laboratories’ Battery Abuse Testing Laboratory investigator Joshua Lamb.

“What we don’t have with battery technology is the 100-plus years of dealing with them to know exactly what the hazards are.”

Researchers worldwide are seeking less-flammable materials that produce similar levels of efficiency to those used in lithium-ion batteries. Others are developing new materials to help contain the heat generated by the failure of a cell.

Meanwhile, are EV batteries safe?

“The answer is yes, but only if certain safety measures are followed,” the University of Navarra researchers conclude.

“Systemic measures, like advanced fire suppression systems in public spaces, are critical, but individual EV owners also play a vital role in minimising risks.”

The presence of emergency cut-off devices and fire suppression systems is taken for granted in petrol stations. Similar habits must become second nature for EV charging stations – wherever they are.

And fire officials reiterate that lithium-ion batteries of any type must be approached with caution.

Do not charge them while you sleep. Disconnect chargers once the device is fully charged. Only use the manufacturer’s supplied or approved chargers. Don’t store any of them near flammable materials.

And if you suspect one has been damaged in any way, seek expert advice immediately.

Jamie Seidel is a freelance writer | @jamieseidel.bsky.social

Originally published as ‘Major safety concern’: Fresh EV battery warning following string of fatal fires