Who is the real Anthony Albanese?

In an exclusive interview, Labor leader Anthony “Albo” Albanese invites journalist Joe Hildebrand into his home to talk about the breakdown of his marriage, his humble beginnings and his plans for Australia.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In the middle of last century, a young woman returned to Sydney from a long trip abroad, heavy with child. The father was literally half a world away and betrothed to another. For an Irish Catholic girl in 1960s Australia, this simply would not do.

Young Maryanne Ellery dutifully went to hospital to give birth to her baby, knowing that as soon as she did, the child would be taken from her and put up for adoption.

It was expected that she wouldn’t even lay eyes on this precious thing she had carried inside her. She would instead resume her life, as though nothing had happened.

But a nun at the hospital made a fateful decision, one that would change the course of Australian political history. She brought the newborn back to his mother and placed him in her arms. And young Maryanne Ellery realised she could not let him go.

She took the baby home to her small council flat in an industrial part of inner-western Sydney — a hospital on one side of the block, a factory on the other. She told people the father was dead, killed in a car accident while she was pregnant.

But like any good Catholic girl, she wasn’t going to let such earthly inconveniences alter the child’s good upbringing, nor her good name.

So she took the father’s name as though they had been married all along and gave it to her child so he would grow up knowing that, dead or alive, he was still his father’s son.

That name was Albanese. And that child will probably be the next prime minister of Australia.

MORE STELLAR:

Why Noni Hazlehurst is heading to Hollywood

Rob Mills: ‘Stop asking me about Paris Hilton’

FIFTY-SIX YEARS later, dispatched by Stellar, I’m knocking on the door of a modest Federation-era house in the messy suburb of Marrickville in inner-west Sydney. There’s a pair of thongs on the porch and a nondescript Toyota in the drive.

The man who everyone simply calls Albo answers the door in jeans, bare feet and a football jersey. It’s his first day off in three months.

The house is as relaxed and informal as his clothes. It’s certainly a long way from the council flat he grew up in, but it’s far from fancy.

There’s stuff lying around, signs of interrupted activity and unfinished odd jobs. In short, it’s normal.

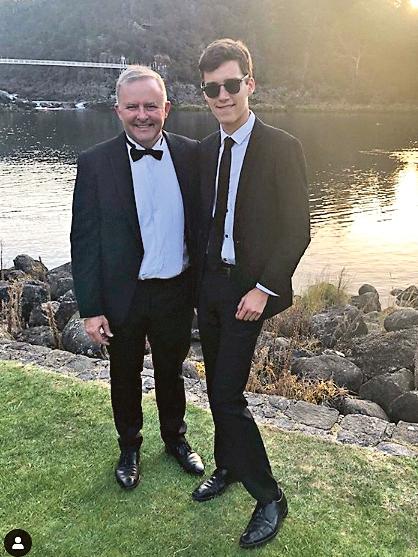

He lives there with his 18-year-old son Nathan and jokingly laments about what the kid gets up to when he’s away. Because these days, he’s away a lot.

Right now, the newly minted opposition leader, formally known as Anthony Albanese, is finishing up a post-mortem “listening tour” of Australia.

He’s already been from Queensland to Western Australia, and is about to cut up the middle from Adelaide to Darwin.

Once that’s done, he will have visited every single state and territory in the country in an effort to find out why Labor lost the unlosable election.

It is part of ALP folklore that Maryanne Albanese instilled in her son Anthony three great faiths: the Catholic Church, the Australian Labor Party and the South Sydney Football Club. So far, only the Rabbitohs have had a good year.

It has also been a hard year for him personally. In January, his marriage of 19 years, to fellow Labor luminary Carmel Tebbutt, abruptly ended after 30 years together, something that deeply shocked him and something he is still clearly struggling to understand.

“Yeah it has, it has been a difficult year,” he says. “But life can be complex and difficult.”

He doesn’t want to delve into the reasons why. There were no third parties involved, and who really knows why relationships end anyway? Sometimes they just do.

I’m reminded of the Paul Simon song ‘Graceland’, in which he sings: “Losing love is like a window in your heart, everybody sees you’re blown apart...”

There’s something slightly blown apart in Albanese’s eyes when he talks about his once-great love. Why wouldn’t there be? And, like Simon in the song, Albo is going on a journey with his son.

“Yeah, he spends time at his mother’s as well, but the time we have here, now that he’s emerged...” he says with a laugh.

“You know, teens go through a period of non-communication, but it’s good for us to have time together and we are very close, and I try to make sure I’m sitting down with him and having quality time and talking about how he’s going.”

Nathan’s going great, incidentally. He did his HSC last year and is now studying business at the University of Technology in Sydney.

More importantly, he has a strong group of friends he has known since primary school. Albo, an only child himself, is more proud of this than anything.

There is something about men with absent fathers, I think, that makes them desperate to be there for their own children.

I ask if he and Tebbutt deliberately decided to just have the one because, as top-level politicians, that was all they felt they could give enough time and attention to.

“No, it wasn’t a choice, it’s just what happened,” he says, though he remains ferociously aware of how hard it is for politicians to raise kids.

“It’s a big issue with being away, it’s a big cost of the job,” he explains. “But I tried to make sure I was there for things like the weekend sporting fixtures. Spending time with him was sacred.”

Speaking of sacred, what about his other great pillar of faith? How long is it since he has been to Mass?

There is an old Catholic joke about a church that is infested by a horde of bats that no-one can get rid of. After every exterminator has tried and failed, the townsfolk call in a priest and the next day the bats are gone.

“Did you kill them, Father?” they ask.

“No, I baptised them,” he says. “Now they’ll only come back at Christmas and Easter.”

But Albanese isn’t your conventional Christmas Catholic. He still goes to church but only on occasions that matter to him personally. One, he doesn’t want to talk about. The other was his late mother’s birthday. He laughs as he recounts how excited the priest was to see him.

As usual, Albo is typically atypical. He runs his own show. For the past six years he was the only shadow minister allowed to issue public statements without approval from the leader’s office — although perhaps “allowed” is the wrong word. Nobody dared tell him not to.

It was the same when he was a kid living in that public housing flat in Camperdown. His mum worked nights as a cleaner until she was crippled by rheumatoid arthritis and forced to take the disability pension.

During her many long stays in hospital, the teenage Albanese would take care of the flat on his own. Sometimes the neighbours next door would offer him dinner. All poor, all Catholic, all Labor, all taking care of each other. It made him.

![“I tried to make sure I was there for things like the weekend sporting fixtures. Spending time with [son Nathan] was sacred.” (Picture: Steven Chee for Stellar)](https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/3dabefb88ee94ed8eee713eeda30a4b6?width=650)

“I don’t recall anyone saying they voted anything but Labor until I was in my teens,” the now 56-year-old admits with a laugh. “I thought that was just what you did.”

IN THE AFTERMATH of Labor’s shock defeat on May 18, I was talking to a mate of mine in the party about what went wrong and whether Albo was the answer. He recounted a theory that was put forward to him by another party operative.

“All you have to ask yourself,” the guy told him, “is what does Bill Shorten do on his day off?”

He didn’t know, my mate didn’t know and I didn’t know — and we were all people who were supposed to know. So if we didn’t know the real Bill Shorten, how on earth was the Australian public supposed to?

With Albanese, on the other hand, it was easy. You could picture him at the pub, chatting to mates with a beer in hand; at the footy, cheering on his beloved South Sydney Rabbitohs; or at a gig, singing along to his favourite Pixies song.

In short, Shorten was inscrutable. Albo was, well, Albo. Even if you didn’t know him, you knew him.

Now the question is whether after the brutal chaos of the Rudd-Gillard governments and the bloodless discipline of the Shorten opposition, he can lead Labor back from the wilderness and restore it to power.

One thing he definitely won’t do is fall back on the divisive “us and them” rhetoric that clearly turned so many Australians off the Shorten ALP.

Despite being nominally of the left faction, Albanese has consistently been a far more moderate and pragmatic voice than the nominally right-wing Shorten.

If anything, he is cast in the mould of the great consensus-builder Bob Hawke, whose death left a spiritual hole in the party in the last days of the campaign.

Indeed, perhaps the greatest irony of Albo’s listening tour is that it didn’t teach him much about Australia that he didn’t already know.

“It’s confirmed to me that Australians are pretty generous people, and I think there is a lot of discussion that tries to pit Australians against each other falsely,” he says.

“All Australians are concerned about jobs and their standard of living. The nature of those jobs might differ depending on where they’re living, but everyone is concerned about those issues.

“They all want a better standard of living for their kids, they all want an environment that’s as pristine as the one they’ve enjoyed. And they want success for themselves but also for their community and the country as well.”

Australians might also get their first single dad in The Lodge. Should we be worried about house parties then?

“I think the truth is that politicians, by and large, end up working so hard that people are voting for them, not their circumstances,” Albo says with diplomatic restraint.

“Certainly my circumstance isn’t unique.”

He tells Stellar he is still on good terms with Tebbutt and speaks with her regularly. Moreover, he insists that mention be made of his cavoodle Toto, who he walks every day and who surely risks compromising his reputation as a Labor hardman.

“Yeah, we still have contact,” he continues quietly. “And we share custody of our son and dog.”

READ MORE EXCLUSIVES FROM STELLAR.

Originally published as Who is the real Anthony Albanese?