Serafina Tané was born into a doomsday cult, and in her early years expected to be hunted down and killed. But when the cult collapsed, she broke free of beliefs that bordered on madness.

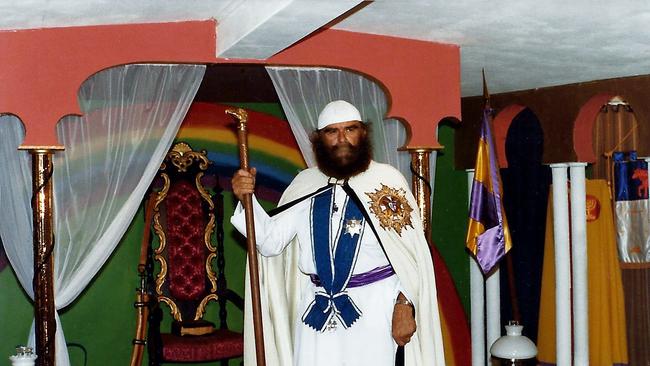

SERAFINA Tané’s family followed a charismatic prophet called Douglas Metcalf who claimed God anointed him the Messiah.

Follow me and you will be saved, he told Serafina’s parents who gave away everything to join a New Zealand commune known as Camp David on a farm in Waipara on the South Island.

It flourished for a couple of decades until the late 1990s.

Now a warm and open woman who works hard, particularly among Adelaide’s homeless, to make a positive impact on the world, Tané grew up believing she would be dead by the time she was 20, gunned down by those who hated Christians.

It has taken two decades for her to come to terms with her past and climb out of the framework of crazy beliefs inspired by the Book of Revelation that once ruled her every movement.

Tané’s father, who as a young man was in the New Zealand air force, believed Metcalf when he said if one member of the family could be saved, the rest would find salvation.

“Dad took it on himself to think he could save everybody,” says Tané, who is well known around Whitmore Square.

“He gave up work eventually and worked full-time on the property – he was responsible for the animals, the horses the sheep and the goats.”

The beliefs Tané lived with every day she now sees bordered on madness.

But when you are growing up and this is your world, you believe what your parents tell you.

Serafina is her adopted name; she was christened Miriyum, with an extra “y” because six was the Devil’s number, something all Christian fanatics fear.

“We were told there will be false idols and we’re all going to be barcoded on the head or the wrist and if you didn’t have a barcode you couldn’t buy anything or function in society,” she says.

“No Christian would get the barcode because it was the Mark of the Beast so when EFTPOS cards came out there was this huge fear.”

These beliefs, which included the women putting salt in their bras each month to cleanse themselves while they were menstruating, don’t drop away overnight and it has taken Tané, now 41, much of her life to see things through unfettered eyes.

It was years before she could experience the world as a place of freedom, fun and joy.

Fear, mistrust, hatred of others, a belief in us versus them fed a doomsday scenario, which is the bread and butter of most cults.

Join us and you will be saved. Close the gates, hide from the world, stockpile weapons, pray together and get ready for the day of reckoning.

Oh, and bring me your young nubile women so I can bless them in private.

“He was a very charismatic person,” Tané says of the man she knew as Uncle Doug.

“He initially had a dream and he used to talk about this all the time, how he got sick and went into a coma.”

He would tell the cult members that when he was unconscious God showed him a closet filled with suits made from skin and told him if he chose the right one he could return to Earth for 15 years, then he would die.

He chose the right one, he was back, but the clock was ticking.

Weirdly, 15 years later, at the age of 68, he did die.

He called everyone together for Friday night movies, although Tané, 13, was too young to go. Metcalf said he felt unwell and left the theatre and some of the elders went outside with him. After about half an hour an elder came in and said that Metcalf had suffered a heart attack and died.

Later, as Camp David was collapsing, they started to piece bits together, how Metcalf a few weeks earlier had been to see one of the members who was in fine health but also had an unexpected, fatal heart attack.

“They wondered if Doug had given him something to make him have a heart attack and then he gave it to himself, thinking he would be resuscitated, which would give him more credibility,” Tané says.

Metcalf’s body was laid out in the vigil room and his followers watched him 24 hours a day, looking for a sign that he would rise from the dead.

He never did.

It was the beginning of the end but it still took years before the revelations of sexual abuse started coming out and families began drifting away.

Doug’s son-in-law, Daryl Metcalf Williams, tried to carry on where Metcalf left off, sexually abusing women.

In October 1995 a longstanding member was questioning why one of the ladies was wearing trousers. The woman turned around and said that Metcalf had raped her when she was 12. When this circulated, more stories of abuse began coming out.

“I didn’t believe it at first. I thought people were just making this up to discredit everybody but then other people were saying it happened to them as well,” Tané says.

How she escaped the abuse she doesn’t know, given she was 13 when Metcalf died.

But she had two older friends, Chloe and Michelle, who were among the women regularly taken to Metcalf’s caravan.

Chloe, in particular, was like a mother to her and she thinks she may have been her protector.

“It’s awful because in a way that’s what it’s about – it’s not about God, it’s about a man who is a sexual predator and wants to have his own little kingdom,” Tané says.

“It about entitlement, money, control and sex.”

But as a child Tané was oblivious and grew up in charge of the compound’s puppies for their first six months until they were ready to go to their owners. She would walk to the river and take her stereo and secretly listen to rock music. It was rebellious and it brought on a very bad feeling because she loved the music and yet it was sinful. She had been warned not even to walk into a music store because bad spirits would attach themselves to her.

“My parents were very strict,” she says.

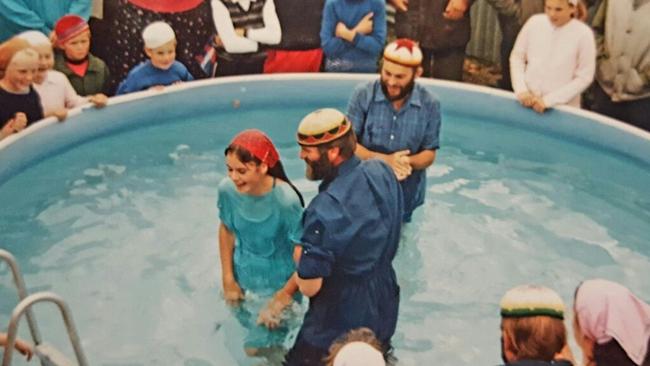

Everyone lived simply and dressed plainly wearing head scarfs or tea cosy hats. When her mother met her father it was the 1970s and she was in miniskirts yet she was married in a conservative frock while he had baling twine around his waist instead of a belt.

There was instant pudding for dessert. There was no Christmas, only the Feast of the Tabernacle in October when Metcalf was born.

A lot of it was a mash of Judaism and Islam, and Metcalf would travel often to the Middle-East and Israel.

Outsiders called them the God Squad but Tané had no idea she was in a cult.

In her teen years she began to be troubled why only the followers of Douglas Metcalf were to be saved. It made no sense that God would leave the rest to rot in hell.

“I would spend half the time crying about it because if they had the answer then why didn’t God show himself to more people? Why had he chosen us? What about people on the other side of the world?” she says.

But the cult also used fear and intimidation as a weapon.

After the 51-day Waco siege in 1993 of the Branch Davidians by Texas law enforcement officers, which killed 76 people including its leader David Koresh, Metcalf’s successor made the members sign a pledge to follow him to the death.

They had been raided in the 1970s and weapons were seized so it could easily happen again. After Waco, they again stockpiled weapons and were warned by Williams they would be hunted down and killed for being Christians, just like the Branch Davidians.

Asked if she felt loved while she was growing up, and Tané borders on tears.

No one had ever asked her that before and she isn’t sure how to answer. The question is complicated because the harsh upbringing, the fear and deprivation, the absence of affection and the life in an old bus with her parents and three brothers, was all based on a misguided belief that they were on the pathway to heavenly salvation.

“My parents that I know now, my Dad in particular, he is a very loving and kind and gentle person but at the cult he wasn’t,” she says.

“I now know what it is to be loved by my parents but back then we didn’t have that kind of relationship.”

The end was a gradual disintegration that started after Metcalf died and accelerated seven years after his death when the revelations of abuse came out.

The whole cult then dramatically collapsed. People stopped going to meetings and some moved away.

Her parents inherited some family money and, with the help of a loan, they bought a house, an old house in dire need of repair, with holes in the floor, but it was a home.

Tané’s mother then took on the person looking after the 40.5ha property who was trying to form an alliance with another cult, from the West Coast, and wanted to shift to the Waipara property.

But it was being held in trust for those who had given everything to establish it.

“My Mum got wind of it and thought ‘no you don’t, you’re not going to ruin other people’s lives’ and she took it upon herself to stop it. She rang everyone who had left,” says Tané.

It boiled down to a fight over trust money and, in the end, the property was sold and trust members over the age of 20 when it broke up got a very small amount.

But Tané was proud she did it.

“She was fighting because it was the right thing to do,” she says.

“I learnt from both of them about adaptability and that you’re not always who you are; you can change and grow as a person.”

Tané struggled to find her place in the world. There was the inevitable discovery of alcohol and parties, and she remembers walking into her first house expecting to see goat horns sprouting from the walls.

Instead it was a bunch of people having fun and the house was clean and tidy. People were open and friendly and you could join in a conversation, even if you knew nothing about music or popular culture.

“(One day) we all sat around and watched Wayne’s World and we had never seen anything like that,” she says. “It’s still one of the funniest films I have ever seen because I didn’t know they made films like that.”

After leaving school at 17, she did a course in office technology and started work as a claims officer for the Accident Compensation Corporation in New Zealand but then decided she wanted to travel.

She hadn’t expected to be still alive and now her whole life was in front of her.

“We were taught that we would be hunted and killed for being Christians, there was always that doomsday thing, from Revelations,” she says.

“It’s what all Christians fear. It’s when the Devil is going to take over the world.”

She moved to Melbourne where she managed an internet cafe in St Kilda then to Europe.

She visited Morocco after the 9/11 terror attacks, talking to people and hearing their perspective. “I knew how to talk to people in that religious way,” she says.

“I stayed out in the desert and it was so peaceful. It was my first experience of people just being themselves from the heart and having a really simple way of life.”

After Europe she returned to New Zealand and met a man with whom she had a son, Noa.

It was then she decided to change her name and recognise the person she had become.

She was called Minnie in the cult, an abbreviation of Miriyum, but after having Noa she was ready to inhabit a new identity.

She chose Serafina after seeing a Nicole Kidman movie, The Golden Compass, featuring a witch called Serafina Pekkala.

“I loved that name; I almost changed it to Serafina Pekkala but it was too story bookish. I changed my last name to Tané which means Maori god of the forest and it was Noa’s dad’s last name. I wanted us to be a family unit,” she says.

She made her parents call her Serafina and stuck to her guns so even they know her as Serafina now. “It’s a new birth that you’ve given yourself,” she says.

She had heard that Adelaide was an interesting place for artists and when she came here she loved it. She returned to New Zealand a couple of times but now it’s her home.

She feels attached to it and has found a community in which she can be active, particularly the southwest of the city.

Meet Tané and she is warm, open, happy and committed to living an ethical life.

She is a self-made woman who got where she is on her own because there was no-one to help her to overcome the trauma of her upbringing, no counselling, no government support.

Her parents were dealing with their own loss of faith and were in no position to help.

When she went home her father would lock himself in the bedroom and not come out until she one day asked her mother if he didn’t love her any more.

“She said, ‘he feels like he’s ruined your life and he doesn’t want to keep doing that’,” she says, crying. “I think that was a turning point for me, to hear that my dad felt that way, and to see him being vulnerable. I said, ‘no, we love him, we need him in our lives, it wasn’t him, it was the cult’.”

It was a pivotal moment for the family and the healing began from there. Her parents are still together, in love and happy, and her mother has exerted her independence after spending years as a subordinate household member.

Out of the blue in Adelaide Tané met a soulmate, now her partner, d’Arcy Lunn, who grew up on Yorke Peninsula and travels the world living a stripped back, minimalist life dedicated to the foundation he established, Teaspoons of Change.

It thinks small and starts in classrooms around the world, which become part of a global education network dedicated to having a positive impact on people and the planet.

Tané who works with Lunn on Teaspoons of Change, a couple of years ago gave her first talk about living in a cult and it was the first time she felt her life fall into place.

When she had worked in offices she was warned not to bring up her background because it would scare people off. Now she could accept it as part of her life.

She realises now that cults are not about religion, they’re about thought control. And the people who are attracted to them have their own reasons for submitting.

“That’s the thing; people are looking for something but I think the answer is inside you,” she says.

“A lot of the people at Camp David were just a bit odd; people looking for acceptance. If you’re looking outside, you’re going to be manipulated by other people.”

Serafina is the South Australia contact for Cult Information and Family Support (CIFS) for people who have left a cult, or know someone who has joined.

She can be contacted through CIFS info@cifs.org.au

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout