Vietnam War: Australian Army Training Team reflects on 50-year anniversary

They were part of Australia’s most decorated unit of the Vietnam War. But why did they trade a slouch hat for a 50-ton American tank?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Test your knowledge of news, sport and pop culture in Brainwaves

- More great features from SAWeekend

- How to get the most from your Advertiser digital subscription

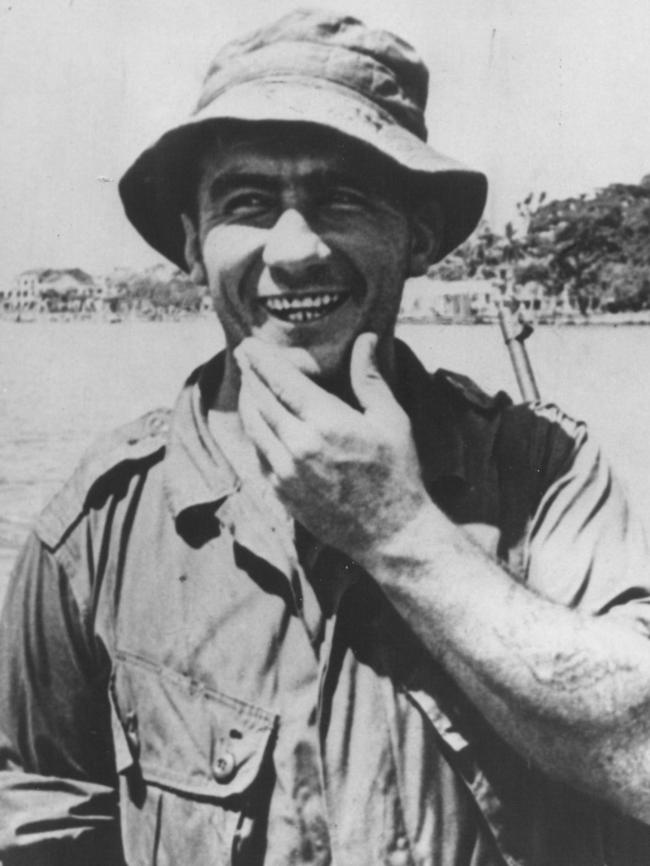

‘How much for the tank?” Ron “Jack” Boyce asked the credulous Americans minding a depot of army surplus vehicles in Vietnam.

After a short negotiation, Boyce picked up the M60 tank – unit price $US481,911 – for a slouch hat.

Yes, Warrant Officer Class II Boyce traded an Australian hat for a 50-ton American tank. Boyce had pulled off the deal of the century but there was a catch – the tank had no forward gears.

No worries, Boyce told the Yanks while tossing them the slouch hat, clambering on the tank and reversing it to his base in Da Nang. The tank’s main gun and machineguns worked fine, so added much-needed grunt to his outpost’s defensive firepower.

“You had to be a conman,” Boyce, now 76, says in explaining the multifaceted role of an Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV) soldier.

Yes, the men of “the Team” needed to be conmen, scroungers, negotiators, diplomats and social workers. But most of all they were warriors. Warriors who 50 years ago this month were awarded the US Meritorious Unit Commendation, giving every Team member the right to wear a scarlet ribbon above their medals set.

It was a high honour, recognising the Team’s “undaunted courage” and “unexcelled initiative” in Vietnam.

First in and last out, the Team was in Vietnam for 10 years and four months. Fighting and dying alongside the South Vietnamese units they trained and advised, the Team was the most decorated Australian unit in Vietnam.

Its 990 men were awarded four Victoria Crosses, 20 Distinguished Conduct Medals, six Military Crosses and 15 Military Medals. The “adviser” tag was misleading: The Team fought hard fights throughout South Vietnam. Thirty-three were killed and 122 were wounded. Two of its VC recipients – Warrant Officer II Kevin Wheatley and Major Peter Badcoe – were killed in the action for which they received the award.

Wheatley, Badcoe and their fellow VC recipients Ray Simpson and Keith Payne were the tip of a very long spear. Nine of the Team’s 33 dead were decorated posthumously. Men of the Team fought more battles than any of the Australian infantry battalions sent to Vietnam.

The Americans showed their gratitude by arranging a high honour for their Australian friends. On September 30, 1970, AATTV paraded at Vung Tau to be presented with the Meritorious Unit Commendation by the US commander in Vietnam, General Creighton Abrams.

It was a glorious occasion for the Diggers, but not so much for the General, who had a heart attack and was rushed to the nearby Australian hospital, where Abrams’ entourage bundled a Team soldier out of his sick bed because he was deemed a security risk. In the award citation, the Americans co-opted the Team’s motto to praise AATTV’s “relentless perseverance”.

“Persevere” is an apt battle cry, for the Team had to apply patience and determination in advising and training the South Vietnamese units to which its members were attached.

Small teams of Australians – in some cases single Australians – were posted to local units. The Diggers were elite soldiers; many were Korean War veterans and almost all were officers or non-commissioned officers.

To make the grade, they had to pass an exacting course in Australia. “It was a hard course because our instructors were a lot of old soldiers and warrant officers who were as tough as hard nails,” Boyce says. “It was a tough course but a very fair course.”

Bound and blindfolded candidates were left in a Sydney seaside cave while the tide rose. As the water lapped at their legs, the men went to war with their own imaginations – was that a lump of driftwood or a shark?

“That was when we lost a few blokes,” Boyce, of Overland Corner, says. Only five of Captain Len Opie’s intake of 58 men made it through – four young commandos and Opie the decorated World War II and Korean War hero. The men of the Team were experts in their fields. Boyce, for example, was a heavy weapons specialist.

“I wanted a change. And I don’t regret it. I’ve made some really great mates from the Team. I think it was a better experience than being with the (infantry) over there. You weren’t restrained by battalion or Task Force orders. You weren’t restrained by petty authority. You were almost a freelance agency.

“You were advising the (South Vietnam) battalion commander. You’d never tell them, only advise them, because they couldn’t be seen to lose face in front of their men.

“You could never say ‘do this or do that’. You could suggest something and when they went with it you’d say ‘well done’. You had a big influence in the way they operated.”

And the way the Vietnamese operated made a big impression on the Australians. When Boyce’s Vietnamese bodyguard committed some minor infraction, his battalion commander drew his pistol and shot the poor man in the leg.

Like Boyce, Warrant Officer II Ken “Snow” Chester was an expert scrounger. While he never bagged a tank, he did procure, in one deal, seven trucks, three low loaders, a jeep and a trailer, all full of food, sandbags, plywood, cement and “any other construction material I could find”. All for two bottles of bourbon and a night on the grog for the Americans who handed over the merchandise.

“The Yanks couldn’t get a lot of booze but we could get what we wanted,” Chester, 80, of Elizabeth North, says. “The Yanks just loved Aussies. Loved Aussies.”

Chester loves Aussies too. He has honoured his fallen mates by arranging a row of 33 Australian flags – one for each of the Team’s war dead – beneath the Royal Australian Regiment’s memorial cross at its Linden Park clubrooms.

He remembers Vietnam as an unconventional war against an unknown enemy. Where danger was all around but could only be detected with a trained eye. He remembers muddy puddles beside a road flanked by trees that had gone all yellow at the top – the telltale signs of danger beneath. A secret bunker.

Chester poked around in the dirt until he found the bunker’s entrance and pulled out a young woman – the same young woman who served him beers at a bar in town.

“You just never knew. We were all scared. But we controlled it. The war was a maturing episode for me. As a young soldier realising you could be killed tomorrow, it makes you grow up pretty quick.”

They who grew up in Vietnam are growing old. AATTV state branch president Mick Dolensky says there’s about 300 men of the Team left Australia-wide.

“We lost a few more last week,” Dolensky, 70, of Salisbury North says. If anything, the bond between Team members grows stronger as the numbers dwindle.

“We were a small band of men,” says Dolensky, who went to Vietnam as a medic in 1970-71. “Roughly a hundred in the country at any one time. So there was a lot of camaraderie and mateship. We were small in number but big on mateship. We all looked after each other. And we still do.”