Victim Support Service founders: Why has Vickie Chapman axed our funding?

First, their children were murdered. Now Vickie Chapman has axed funding for their support group. They want to know why.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Myk Mykyta is no fan of Vickie Chapman. The 84-year-old’s description of the Attorney-General, uttered from his well-worn armchair in a loungeroom crammed with books, is unpublishable. The source of the retired theatre critic’s displeasure is Chapman’s recent move to strip funding from the state’s pioneering Victim Support Service (VSS).

Established 40 years ago by Mykyta, his late wife Anne-Marie and other parents who had lost children to serial killers, murderers and sexual predators, what was originally known as the Victims of Crime Service is widely regarded as a world leader in victimology.

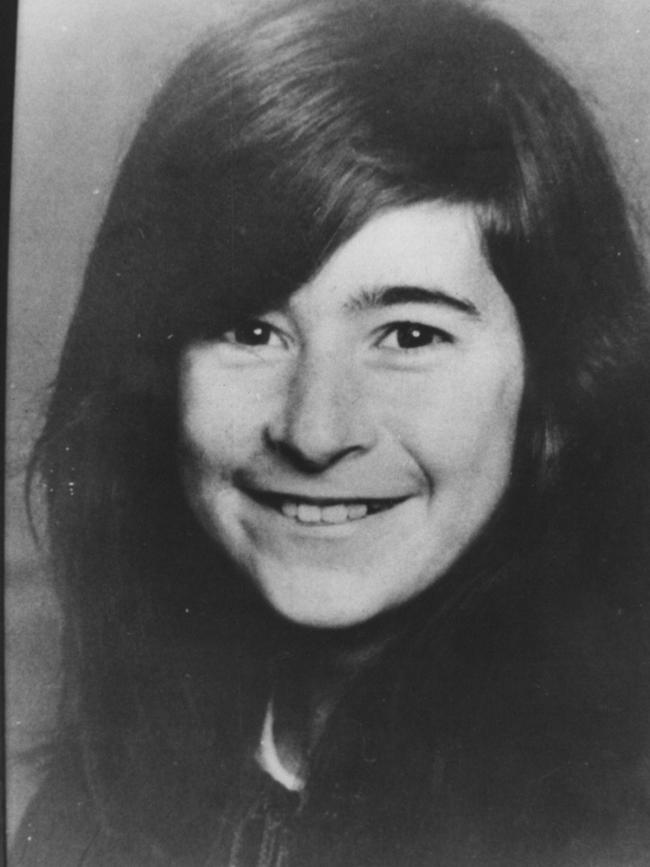

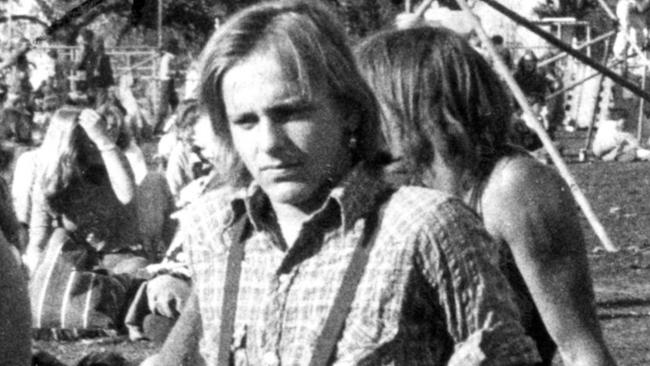

The Mykytas worked with a former Queensland police commissioner, Ray Whitrod, in the late 1970s to set up the organisation in the aftermath of the death of their 15-year-old daughter, Julie, in what became known as the Truro murders. They were joined by Judy Barnes, the mother of one of the young men killed by a group known as “The Family” and Les Ratcliffe, the father of one of two girls abducted from Adelaide Oval in 1973.

“We wanted to call it the Victims of Crime Service or VOCS because, in Latin, ‘vox’ means voice,” explains Mykyta. “Now, thanks to Chapman, that voice has been silenced.”

Mykyta is referring to a decision by Chapman to hand a contract for crime victim counselling services to a private provider, effectively stripping VSS of the majority of its work. Chapman awarded the three-year, $2.4m contract to Relationships Australia SA in June. The new arrangements took effect in early July, resulting in the closure of most of the services offered by VSS from a city location and seven regional offices across the state.

Along with personal counselling with experienced trauma specialists, access to a court companionship program and well-stocked resource centre on dealing with psychological trauma has been downgraded. Victims needing advice to prepare impact statements for court hearings are now directed to the office of the Victims Rights’ Commissioner within the Attorney-General’s Department, which has received an extra $252,000 in funding to help them. VSS has been left with two key programs, helping victims of domestic violence and providing court companions, relying on volunteers to provide the service.

The organisation has been forced to get rid of 25 staff. Two-thirds of victims it was helping have transitioned to Relationships Australia. The remainder have found private counsellors or chosen to stop seeing someone. The library, with its extensive collection of books and resources on dealing with trauma, has closed while front desk support at street level also has ended.

As far as Chapman is concerned, Relationships Australia demonstrated it is capable of providing a similar service when bidding for the contract. “I appreciate the work the Victim Support Service (VSS) has done in the past, and is continuing to do,” she says.

“The independent tender process was competitive and extensive. It recommended RASA as the most effective and comprehensive service provider, having had more than 70 years’ experience in victim support and counselling. The Marshall Liberal Government is committed to providing the best support for victims of crime through our justice system.”

Mykyta begs to differ. He says it is heartbreaking to witness the demise of an organisation which grew from a volunteer group based in a city church to an internationally-renowned network of volunteers and professionalswhich has helped more than 56,000 traumatised victims of crime, sexual abuse and domestic violence over four decades.

Mykyta remembers going with his wife to a meeting at Whitrod’s house in Adelaide’s western suburbs in late 1979 to discuss establishing a support group for victims of crime. It was not long since he and Anne-Marie had buried their daughter, whose body was discovered in a paddock at Truro, on the eastern edge of the Adelaide Hills, two years after being abducted from a city street and killed.

Julie Mykyta’s killer, Christopher Worrell, died in a car accident before he could be charged with her murder and that of six other young women. But his homosexual lover and accomplice, James Miller, was arrested and charged. Anne-Marie attended all of Miller’s court hearings and was there when he was sentenced to life in jail.

The Mykytas, from affluent Adelaide suburb St Peters, originally were told by police that Julie had likely run away and not to be too concerned. As the months passed, and turned into years, their relationship suffered considerable strain until the missing teen was finally found. It was during their long wait for news that Judy Barnes telephoned their home one night, seeking help from Anne-Marie after the brutalised body of her son, Alan, was found dumped in a northeastern reservoir. He would be the first of five young men killed by a group of men associated with a chartered accountant, Bevan Spencer von Einem, and dubbed “The Family”.

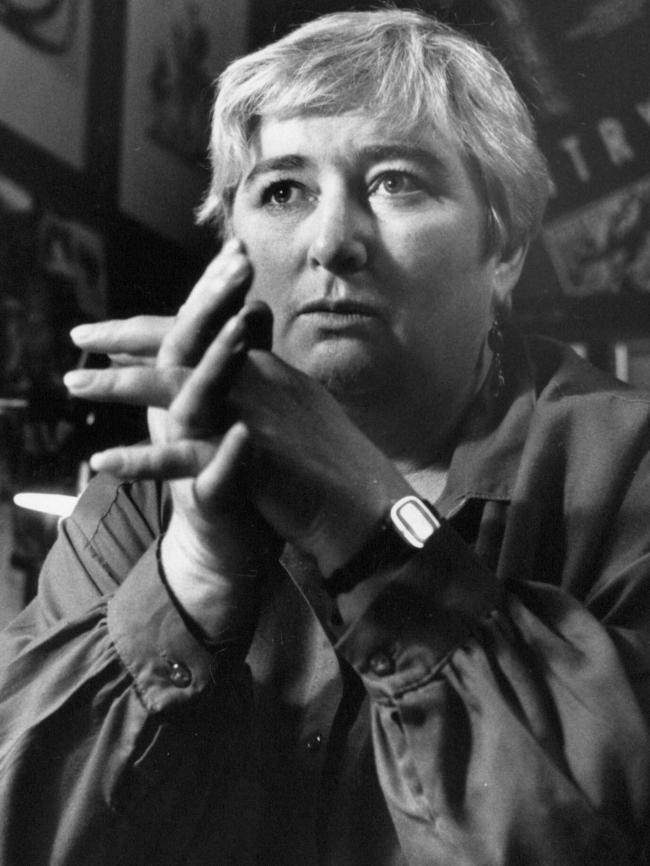

Barnes had seen Anne-Marie being interviewed on television about Julie’s murder and wanted her advice on how to cope with sudden, inexplicable loss. The two women began comforting each other, before reaching out to Ray Whitrod.

“Ray was quoted in The Advertiser suggesting there should be a support group for victims of crime,” Mykyta recalls. “Anne-Marie read the article and called him. She had already gotten to know Judy because she tried to help her after her son was murdered. The pair of them told Ray they thought a support group was a good idea.”

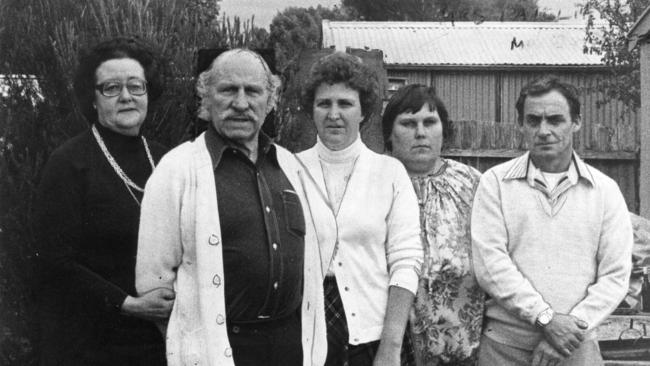

The Mykytas, Judy Barnes, Les Ratcliffe, his wife Kath and their young daughter were among a group of about 15 people who assembled in Whitrod’s loungeroom. Others included an office worker shot carrying his company’s payroll, the editor of a country newspaper viciously assaulted in his home and another couple whose daughter had been murdered. While Whitrod’s wife, Mavis, served tea, coffee and scones, the devout Christian explained how he had been at a meeting discussing prisoner rehabilitation when a woman had questioned what was being done to help victims of crime, especially those involving violence. Mykyta says as the afternoon progressed and individuals broke longstanding silences to share their stories for the first time with strangers who understood their grief, it was obvious there was a need for a support group.

“Anne-Marie, Judy and Les all spoke about how it was important for everyone to help each other. Others opened up about how it was important to communicate with others who had experienced similar things.

“What did we have in common with Judy Barnes? Nothing, except the common fact that our children had been murdered. Socially, we didn’t get together. But when we did get together, it was a helpful and healing experience.

“I think saying things that you can’t really express in other circumstances is extremely useful, socially and emotionally. It helps to know, even though it is a hellish kind of knowledge, that you are not alone and that there are other people who have been through a similar experience.

“Most people tend to glaze over and tell you ‘to get over it’ and that sort of stuff, no matter what sort of connections you have. The reality is that you never get over it.”

Mykyta says the meeting convinced Whitrod he was pursuing the right course.

“Ray was very helpful and very determined that there should be a more formal way of people being helped rather than just relying on people ringing each other in a fairly random way.

“As a result a public meeting was held at the Flinders Street Baptist Church in the city a few months later and the Victims of Crime Service or VOCS was formed.”

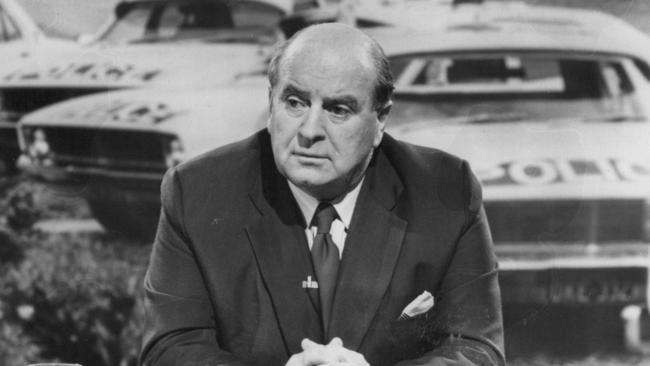

Although initially reluctant to become actively involved in running the Victims of Crime Service, Whitrod found himself its first, unpaid executive director. His wife became its voluntary manager and organiser of its groundbreaking court companionship program.

A former Queensland police commissioner who resigned in protest against corruption within the Joh Bjelke-Petersen government, Whitrod had been hoping for a much quieter retirement than what would eventuate.

Within 12 months of its formation, VOCS – the first of its kind in Australia – had 1800 members. Its rapid growth sent Whitrod on a path which would earn South Australia global recognition for its commitment to supporting victims of crime.

Among the regular speakers at the group’s meetings at Flinders St

reet was a young Labor Attorney-General, Chris Sumner. Together with Whitrod, he would work tirelessly throughout the 1980s and 1990s to enhance legislation protecting the rights of crime victims.

In 1979, Sumner initiated an inquiry picked up by his successor, Liberal Attorney-General Trevor Griffin, into the establishment of a fund which would use money raised from court-imposed fines to pay compensation to those affected by crime. It was the world’s first such levy.

In 1985, Sumner and Whitrod went to Milan to convince the United Nations to endorse the first international Declaration of Rights for victims of crime, a treaty initially not supported by the Australian government. Four years later, Sumner successfully introduced legislation to enable victim of impact statements to be presented in court – the first state in Australia to do so. Like Myk Mykyta, Sumner is devastated by what has recently happened to the Victim Support Service, which, after moving between several city locations, had based itself in an office building on Franklin Street, near the state’s main court precinct.

Sumner says the organisation always had received financial support from the Attorneys-General who succeeded him, regardless of political persuasion, from Griffin to Labor’s Michael Atkinson and John Rau. The only exception has been Vickie Chapman.

“I just cannot understand why she has done what she has done,” he says. “Nobody can. Victims have always been able to go to VSS as a one-stop shop accessible from the street and get access to all of its services from counselling, assistance with their victim impact statements to using the resource centre.

“Now, traumatised relatives of homicide victims are having to go down to Hindmarsh for appointments at Relationships Australia and sit in waiting rooms which might have people involved in family counselling or some neighbourhood dispute.

“If they want to see the Victims Rights’ Commissioner, they have to go to another office in another building in the city. As for regional areas, offices have closed and counselling has to be done remotely or victims need to drive to Adelaide.

“The court companionship service, which has done a vital job, has been downgraded and is now relying on volunteers and little funding to keep going.

“All of the work done over 40 years building up the service has been destroyed.”

Among those who played critical roles in the development of the organisation were chief executives Andrew Paterson, David Kerr and Michael Dawson. The trio each grappled with funding problems and increasing demand but it was Dawson who transformed it from a volunteer-driven support group into a professional counselling service during his 13-year tenure. It was his idea to change its name from the Victims of Crime Service to the Victim Support Service to modernise its image – and clear up confusion with the police Victims of Crime Branch.

Dawson says he is gutted by Chapman’s decision to shift trauma counselling to Relationships Australia, arguing victims of crime need highly-specialised personal support, often for lengthy periods.

“Since the announcement I have experienced a sense of loss, grief and injustice over what has happened,” he says. “One of the most conclusive findings in my time as chief executive was that the greatest strength of the counselling provided by a specialist crime victim service was that therapeutic counselling was actively integrated with the provision of information about the criminal justice system.

“The majority of victims need accurate information from experts with knowledge about the criminal justice system and how they will be participating in that process going forward.

“This need is compounded and complicated by the need for professional counselling and assistance with their problem-solving and resilience-building.

“A generic counselling service with general counsellors, no matter how effective they are, does not usually have this experience unless they specialise in seeing many crime victims and have supported them through the phases of the often traumatic experience imparted by the formalities of the criminal justice system.”

Dawson was among the many guests who attended the 40th anniversary celebrations last October of the formation of the VSS.

Among those who spoke was Sumner, who recalled the achievements of the 1980s and 1990s.

“I was reminded about how the organisation was, and still is, held in great esteem by victim advocates and academics around the globe – particularly for its role in advocating for the inaugural victims of crime legislation and bill of rights at the United Nations,” says Dawson.

“Later it became renowned for its development of meaningful and effective services for crime victims through volunteers and eventually professional staff.

“Victims’ rights and services were, unusually, prioritised and embraced by all sides of politics – a rare treat with positive outcomes for South Australia.”

Dawson says government funding supported programs such as the court companion service, training police about victims’ rights, an annual victim awareness week, establishing a cross-jurisdictional victims of crime ministerial advisory committee, collaboration with offenders’ aid services in pioneering restorative justice processes and creating outreach services in rural South Australia.

“VSS also became a leader in practical crime prevention and safe house security, particularly in socially disadvantaged areas experiencing high crime rates,” he says.

“It established significant programs for family violence victims in the earliest days of the public recognition of this deep-seated social issue and positively affected victims’ outcomes.”

Dawson says the loss of government funding is “a sad state of affairs for crime victims and the state”.

“VSS was an iconic service and brand that brought international recognition and acclaim of the South Australian criminal justice system. What a lost piece of history and achievement for South Australia.”

Former detective, Michael O’Connell, the first South Australian police officer to be appointed as a victim impact co-ordinator, worked closely with Michael Dawson. O’Connell’s role later evolved into him becoming the state’s first independent commissioner for victims’ rights, a position he held until he was controversially replaced by Chapman soon after the March 2018 state election with a serving senior police officer, Bronwyn Killmier.

O’Connell, who remains active in victimology, says VSS helped many thousands of South Australians deal with the effects of crime, no matter where it happened – domestically or overseas. Among those who sought assistance were the relatives of people senselessly slaughtered in the Port Arthur Massacre in 1996 and the Bali bombings in 2002.

“VSS has assisted families impacted by the most heinous crimes in our state’s history,” he says. “It has walked with victims as they navigate the daunting criminal justice process. Countless victims have been heartened by the support, counselling and advocacy provided by the VSS.

“Staff helped train police, prosecutors and correctional officers, educate judges and accompany victims to court. They have assisted victims to write victim impact statements. As experts, they have made submissions to royal commissions, parliamentary inquiries and so on. They urged politicians of all persuasions to embrace, not fear, victims and their demands.”

O’Connell says it is sad that, for most victims of crime, VSS is a shell of its former self. “Its doors across our state have closed and with that VSS has become the victim. It is neither the 40th birthday present it expected nor deserved.

“Now is the time for the many who have benefited from all the VSS did to express their gratitude – for the grieving parents, the volunteers and the professionals who dedicated themselves to restoring victims. They should not be forgotten, as victims once were.”

Jean is one of the many victims who sought counselling from VSS before becoming a volunteer, later receiving a life membership for her dedicated service. Her parents and sister were shot dead at Croydon Park in 1976 by her sister’s estranged partner, a deaf mute who sparked a national manhunt when he abducted his young son.

“I remember getting to the house and being asked to identify the bodies of my family. I started crying and a policeman told me to stop crying because I had questions which needed to be answered.”

Jean, who did not want her surname published, went to general practitioners for help to deal with her trauma but they were unable to help her.

“I went to three or four places that did counselling, I went to the Queen Elizabeth Hospital but they couldn’t help me. The cost of seeing someone was just beyond us. We had three very, very young children and we didn’t have the money so it was just left as it was.

“As time went by, I just knew I had to do something. I had heard something about this group which had started up and so I rang. It was 17 years after the crime had happened.”

Jean says her phone call was prompted by media coverage of the escape of her sister’s killer while on day release.

“I rang the police and a policeman asked me, ‘What’s it got to do with you?’. And I told him it was my parents and my sister who had been killed. My husband was at work so he told me I had to find somewhere I could stay all day away from our house.

“That’s when I knew I had to do something because my fear had been brought right forward. I rang the Victim Support Service and I started getting counselling. It was the best thing I could have done. They understood why I was angry, why I was hurting and couldn’t get on with life as such. I was losing who I was. It’s hard to explain now.”

Jean says the counselling saved her marriage and, quite possibly, her life.

“You can feel OK until you go in there and you start to talk. The next thing the tears come, your heart’s breaking.

“That person sitting there is somebody who hands you a tissue, they offer you a coffee. It’s that personal touch that helps you overcome how you are feeling.

“They then help you with your victim impact statement, because they know what you have been through and can help you express it. They understand your journey.”

Jean says she became a volunteer with VSS to “pay them back a small amount for giving me back my quality of life”. She got involved with court companionship and public speaking, including lecturing journalism students and police cadets about victims’ rights.

Her main concern with the move to Relationships Australia is whether personalised, long-term counselling, court companionship and help with victim impact statements will remain available, especially in regional areas. “How long is it going to take them to get everything in place to do the same type of things with the quality of counselling that the Victim Support Service has done for 40 years?”

Sharing Jean’s concerns about the future long-term care of crime victims is Sharon Morrison, who was receiving counselling from VSS in June when it lost the contract to Relationships Australia.

Her brother, Geoff Trenwith, died from brain injuries sustained during a drunken altercation with a friend, John Henry Victor Watson, while the pair were camping at Rapid Bay in 2017. Watson was found guilty of manslaughter but served only eight months in prison before he was released.

Following his arrest, a major crime detective recommended Morrison speak to the VSS about receiving counselling.

“My counsellor was just fantastic,” says Morrison. “She was sympathetic and she was knowledgeable. I immediately felt at ease with her and found just talking about ongoing problems following my brother’s death very comforting.

“She was there when I went through restorative justice and met with the man who killed my brother. She would get me to write things down to help me with my victim impact statement. She knew how what had happened had affected me. She told me exactly what to expect in court. She gave me lots of information. Without her, I would have found the whole thing completely overwhelming. I was absolutely devastated and suffering lots of anxiety.”

Morrison says she joined the Homicide Support Group, started by Riverland mother Lynette Nitschke after she sought counselling from VSS following the strangulation murder of her daughter, Allison, at St Mark’s College, North Adelaide, in 1991. Morrison since has become secretary of the group which, with the closure of the VSS office in Franklin Street, ironically is now meeting at the same hall at the Flinders Street Baptist Church where the service was set up 40 years ago.

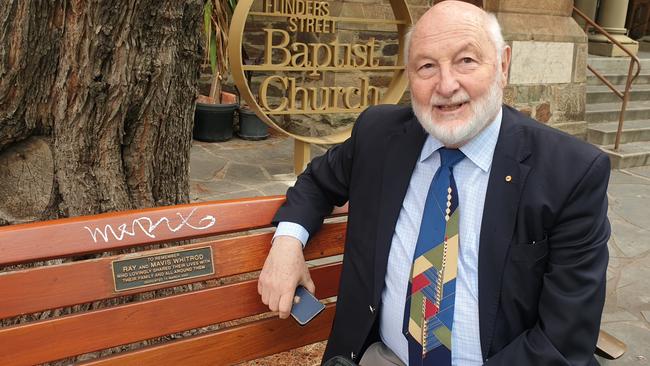

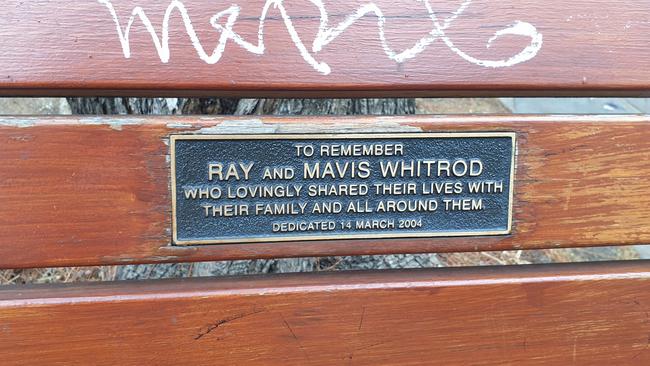

A park bench near its front entrance has a plaque dedicated to the memory of Ray and Mavis Whitrod, who spent countless hours inside the church worshipping or chairing meetings to help victims of crime.

Sitting on the bench on an overcast morning, a reflective Chris Sumner says he rarely has been “so outraged” by a political decision. “The founders of VOCS were true South Australian heroes. They inspired a movement that revolutionised the participation of victims in the criminal justice system and provision of support services. Its defunding is a tragedy that dishonours their memory.”