Dr Anna Sergi and Undercover detective Colin McLaren lift lid on the Calabrian mafia

Dr Anna Sergi grew up in Calabria. She first heard about the Calabrian mafia when she worked out it was why her local journalist father was away so often.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

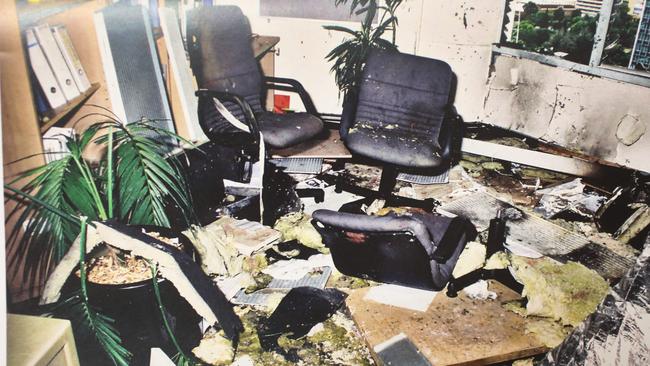

March 2, 1994. 9.15am. A normal city morning hums along as traffic eases. A man settles into his desk at work. Then: a chest-thundering blast, windows shatter and glass spreads across city streets. A desk catches alight. Computers melt in an instant. The flames travel up the ceiling, through the air conditioning unit. The door to the office where the bomb went off slams shut, the ceiling has half caved in.

Frantic workers in the National Crime Authority’s office break their way into the blackened 12th floor on Waymouth St, Adelaide.

They find lawyer Peter Wallis burned all over, left eye already gone, screaming for help. There is also Detective Sergeant Geoff Bowen unconscious but still breathing.

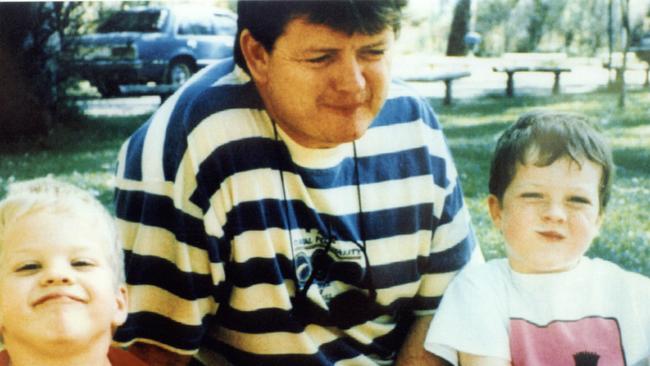

His left arm missing from beneath the elbow. Paramedics arrive. “Not a chance,” they say, and minutes later Sergeant Bowen, a 36-year-old father of two boys aged just seven and five, stops breathing.

It was the day after his wedding anniversary.

That morning a package had arrived for Sergeant Bowen. It was marked “IBM Promotions”. His name was misspelt.

As he began to open it, Bowen turned to a colleague, NCA lawyer Wallis, and said, “It might be a bomb.”

But Bowen couldn’t feel any wires. He continued unwrapping the parcel, using scissors to cut the masking tape.

“There was a loud crack, like a rifle shot,” Wallis would later tell South Australian coroner Wayne Chivell. He added, “Geoff let out a strangled-type cry.”

The next day Bowen was scheduled to testify in a long-running case he was prosecuting as part of his investigations into the Northern Territory cannabis crops and the Calabrian mafia, better known as the ‘ndrangheta.

March 2, 1994, Colin McLaren was in Weipa in the far north of Queensland on a humid morning in a small plane just after 10am – with a bunch of top mafioso.

Before he’d boarded, he had already hidden a gun on that plane. Just in case.

Those mafia men in his midst believed his name was Cole Goodwin, a dodgy art dealer who liked to be paid in high-grade cocaine rock.

Only Cole was Colin – an undercover detective who had infiltrated the ‘ndrangheta stranglehold of Griffith, a dusty town in western NSW, where local anti-drugs campaigner Don McKay had disappeared two decades beforeand whose body has never been found.

Colin was awaiting the cannabis deal he had assisted the mafia set up. The Queensland SWAT team members were lying in the grass in wait.

News hit of Bowen’s death, the two mafiosos on the plane began to laugh when they heard the news.

McLaren laughed along, joined in the jokes.

McLaren had shared olives, wine and Christmas dinner with some of Australia’s top ‘ndrangheta.

He had already come to hate the men who considered him not just an associate, but a friend. Underneath, he wanted them dead and said to himself that morning on the plane, waiting for the cannabis that would never come, “I am going to get these bastards.”

McLaren writes as he speaks, eruditely with polished enunciation and a sharp detail. In his book Infiltration he explains how he developed a hardy taste for adventure groomed through upbringing in the paddocks of Melbourne’s northern fringe in the 1960s.

Living opposite HM Pentridge, big-time crooks had long featured in his imaginings.

Rookie police life began in knockabout Oakleigh in the early 1980s. He came to work with drugs and gangs. He learnt the ways of heroin addicts, Hells Angels, the workings of meth labs, how to be an undercover detective that gets ready access to all three.

Life as a detective took him to the wilds of inner Melbourne where he would experience another seminal event, the Walsh Street murders of police constables Steven Tynan, 22, and Damian Eyre, 20. All four accused of their murders would be acquitted. By the early 1990s, inspired in part by a secondment to America, he moved to undercover.

Those mafia men he met in Griffith would be caught and convicted – for drug conspiracy, thanks to his deft work.

All along, he said, the threat of payback violence haunted him.

He messed with the group that had killed judges, mayors, police officers. Who had kidnapped the son of a rich oil baron’s family, held him prisoner for five months in the Italian mountains and cut off his ear to pressure the family into paying the $3m ransom.

It’s difficult to overstate the reach and power of a mafia whose reach and power never seems to get the attention of organised motorcycle gangs in Australia.

The ‘ndrangheta are among the richest criminal organisations on the planet, born below the fog-covered, rolling hills in Calabria, southern Italy, ingrimtowns of cobbled streets and concentre of poverty and illiteracy and a weak state. About 150 years ago, one group of families out-muscled existing land owners, imposed their own taxes, and became the richest people in the province.

This powerful group became the Calabrian mafia, the ‘ndrangheta, which means the honoured society, replete with masonic rituals.

There are tales of arranged marriages with children as young as 12 to build a clan family, an eye on diversifying its wealth sources; extortion, stock poisoning, kidnapping. Successfully dressing up murders as suicides.

They arrived in Australia on December 18, 1922, when the ship King of Italy docked in Australia and spread heads of the Calabria around the nation.

The gang initially took control of the fruit and vegetable market, terrorised Queensland’s cane field farmers, before expanding to take near total control of the country’s lucrative cannabis trade by growing enormous crops in the Outback. A second wave of immigration from 1947 through to the early 1970s expanded the ‘ndrangheta once more.

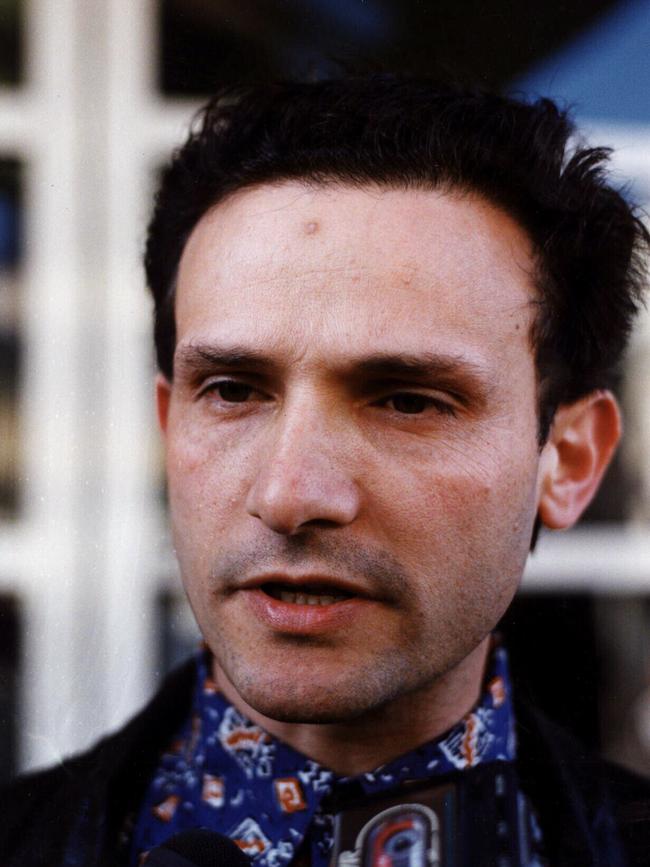

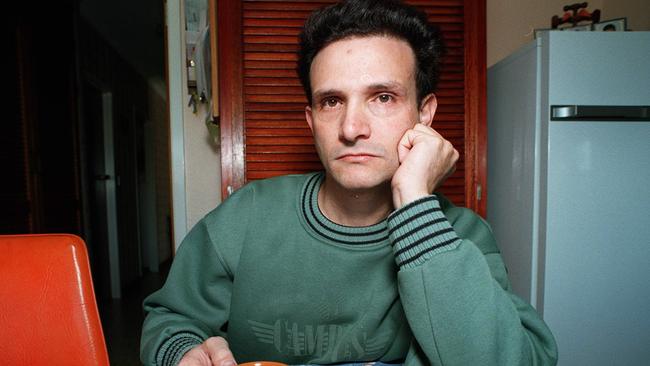

Domenic Perre was one of the 360,000 Italians who arrived in Australia as part of a post-World War II migration beginning in 1947.

Perre, who came from peasant stock, arrived in 1962 with nothing. He built his way up through cannabis cultivation.

He was hot-tempered, smirking yet humourless, a man who craved infamy and influence, a short man whose family origins meant he could never climb the upper echelons of the Calabrian mafia. He collected guns. Sought vengeance. He was angry but he could also be incredibly reckless.

In fact, if anything, his pent-up anger was matched by his recklessness.

McLaren had started to wonder just how high up the ‘ndrangheta’s influence went in Adelaide society since the ship first arrived in Port Adelaide 70 years earlier.

Sergeant Bowen was due to testify against the brother and uncle of Perre in the autumn of 1994.

During the undercover operation, police impersonated Frank Perre, Domenic’s brother, during incoming calls to the Hidden Valley homestead where they discovered a massive cannabis crop south of Katherine, NT, and repeatedly spoke to a caller who identified himself as “Dom”.

Bowen also headed an NCA team that covertly searchedDomenic’smodest brick home in Salisbury, in Adelaide’s northern suburbs, a little while earlier. Perre complained his home had been left in disarray – apparently humiliated by the way Bowen had removed pornography videos from his cupboard and placed them on his bed.

Perre would subsequently be incarcerated in the watchhouse after the raid, missing his mother’s funeral.

A few hours after the NCA bomb went off, undercover police spotted Perre at a nearby multi storey car park gazing without expression at the smoking ruins of the NCA office. Much of Adelaide’s police force, still haunted by the incident, thought the evidence against Perre would be strong enough.

Domenic Perre was arrested within six days but no charges were laid. Police reviewed the case over subsequent years until a 1999 coronial inquest that lasted a record 56 days. However, the case never made it to court.

McLaren, whose skilful undercover work had so far led to 12 mafia prosecutions, got the call while he was in Melbourne. He was then a single father and the very real possibility of retribution was already playing on his mind.

McLaren arrived in Adelaide and immediately got buried in the paperwork. He came to three main conclusions – one Domenic Perre was their man. That Perre was an “intelligent”, “dangerous” and a “difficult target”.

“He was at the height of his career as a criminal. He was growing massive marijuana plants, like massive crops, tens and even hundreds of thousands of plants, worth millions upon millions of dollars right across the outback regions of South Australia and Northern Territory,” McLaren tells SA Weekend.

And after reading everything the NCA had to offer about Perre, he came to the conclusion that the key to nabbing him was the stuff of matchstick tips: red phosphorus.

The letter bomb had been made from red phosphorus.

When McLaren heard this it reminded him of something else – then he remembered what it was, it’s one way to make methamphetamine.

He made a team of undercover operatives all of whom were given characters: a shady male “ugly son of a bitch” with past drug arrests, his wife – “a blonde with attitude”, there was Jack the Maori and Jimmy the cook – an amphetamines cook.

One of them had good knowledge of meth through prior operations. But, even still, McLaren explains, “I put him through a training program on how to become a clandestine cook, a clandestine chemist to manufacture amphetamine.

“I did that over many weeks with a forensic scientist and myself. We trained him up to be a proficient clandestine cook using only the red phosphorus method.

“The strategy was then to eventually get to friends associated with Perre and wait for the right moment because cooks do a lot of dirty talk.”

The plot was to get involved with the mafia by building a drug lab that made high grade speed (powdered meth) and get to Perre step-by-step.

“So, one of the strategies was to infiltrate the associates of Domenic Perre first and get to meet them, get used to them, get to build up rapport, get into quality, and they would then ultimately, fingers crossed, they would ultimately then introduce the operative or two up the ladder and eventually to the man on top, Domenic Perre. And that worked.”

Indeed, when Perre heard about the high-grade meth, he smelt money – the quartet had suggested $20m in profits.

His pals supplied the land on Adelaide’s northern fringes. The lab became operational. It was also bugged. It took three days to make a batch.

“There was a speed laboratory actively cooking, I don’t know, $6m worth of speed (powdered meth), about $6m worth of amphetamines and two of my operatives were in that speed laboratory day and night cooking and making these drugs alongside Perre, alongside three other teen organised crime targets, the Trimbolefamily and another fellow, and five of those mafia fellows.”

Millions of dollars of drugs were produced. Perre was a regular visitor. He spoke in his regular self-aggrandising way. He came to speak of Sergeant Bowen and how he had wished he had “taken out the whole f--king building”.

“We waited for that moment. I called everybody and said we have to make the arrest now and we did. All of the SWAT team came into a remote property outside Adelaide and about 50 police got involved.”

“There were seven (mafia figures) in town. Ultimately they all went off to jail.”

An infuriated Perre got nine and a half years. Nine years for the drug charges only. He would not be charged for the NCA bombing. It had been Australia’s largest and most expensive covert operation.

An exhausted McLaren quit the force and started an Italian eatery in the chilly hills surrounding Victoria’s Mount Buffalo National Park. He carried into those mountains, documents, notebooks, tape recordings, transcripts, pervasive thoughts.

“It just never goes away because you know it’s unfinished business and it’s still lingering. I carried it,” McLarensays.

“I can tell you, Perre was a very serious man, very blunt man, a man without humour and a man that had a lot of pent-up anger and obviously violence within him. There was nothing redeeming. He was in my life for 27 years and it was a burden and I carried documents and notebooks and tape recordings and transcripts with me wherever I moved my house.”

Perre would not serve the full sentence for the drug trafficking charges. He was released after serving a five-year, non-parole period of the nine-and-a-half year sentence in 2001.

Regardless, business was booming for the ‘ndrangheta.

In 2008, the same year members of the ‘ndrangheta were caught for trying to import the world’s largest ever ecstasy haul into Melbourne, a confidential cable released by WikiLeaks showed US officials estimated ‘ndrangheta to have an annual turnover of around $50bn. That’s more thanIceland or Malta or the Mexican and Colombian drugs combined – mainly because of its burgeoning control of the world’s cocaine trade.

Its work was not just drug trafficking but also embezzlement, extortion, usury, gambling, arms sales, prostitution, counterfeiting goods and people-smuggling.

For years, McLaren thought over and over about Perre. He also thought about Geoffrey Bowen.

He thought about Geoffrey Bowen’s son – Matt, who was seven – who has said he remembers that March 1994 morning “being yanked out of a swimming lesson in primary school in mid morning, and being taken home and told what had happened”.

“I carried it,” McLaren says.

In 2018 after a joint investigation lasting more than two years by state and federal authorities including the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission, Perre was charged over the crime 24 years later.

In early 2022, McLaren finally produced his cache of notes and testified as Perre stared him down. There was enough corroboration to convince Justice Kevin Nicholson that Perre was guilty.

In October 2022, after a seven-month trial, Perre was sentenced to life with a non-parole period of 30 years and seven months for the murder of Bowen and the attempted murder of Wallis. Supreme Court Justice Nicholson described the crime as violent, barbaric, and ruthless.

McLaren says when he first heard of Perre’s conviction his thoughts were of Bowen’s family.

“My first thoughts were to his family. I just hoped they were happy. Relieved at least,” he says.

Today the ‘ndrangheta are believed torun “a drugs and extortion business worth billions of euros” in Australia. Millions more have been amassed through real estate and race horses.

In the last two years, it is believed they have surpassed the Sicilian mafia for power internationally.

In mid 2022, a year after authorities launched Operation Ironside, AFP assistant commissioner crime command Nigel Ryan said: “We have identified 14 confirmed ‘ndrangheta clans across Australia, involving thousands of members.”

Ryan said, “The ‘ndrangheta are flooding Australia with illicit drugs and are pulling the strings of Australian outlaw motorcycle gangs. They have become so powerful in Australia that they almost own some outlaw motorcycle gangs who will move drugs around for their ‘ndrangheta financiers, or carry out acts of violence on behalf of the ‘ndrangheta.”

Australia is effectively now seen as an arm of Italy for the ‘ndrangheta.

Dr Anna Sergi grew up in Calabria. She first heard about the ‘ndrangheta when she worked out it was why her local journalist father was away so often.

Later she would hear about the kidnappings and notice the subsequent hovering helicopters.

One day, two ‘ndrangheta escapees even knocked at her grandmother’s house, looking for help.

Now a professor in the school of sociology at the University of Essex, she has published 11 books on organised crime. She has spent most of her life dedicated to studying the ‘ndrangheta.

She says, ’ndrangheta is suspected to effectively be run by a committee of older men with links – by family or marriage to Calabria.”

Sergi has identified 11 key families who make up the “dynasty” of the top tier “gatekeeper class” of ’ndrangheta in Australia and run the show from Griffith, Adelaide, Sydney, Melbourne and Mildura.

She told SA Weekend that gatekeepers use other ethnic groups to carry out their criminal activity, all the while working in high-powered jobs as lawyers or accountants.

“A set of surnames that appeared in the public’s eyeand that would fall into this category are, just as an example, Sergi-Barbaro in Griffith (NSW), notoriously mentioned in institutional inquiries about the Honoured Society in Australia,” Sergi wrote in a recently published academic paper.

“In Adelaide, there is a ‘ndrangheta family where the son of this old guy is a lawyer... They have a very good business, venture title, capital, they are not criminal families, not in the sense of organised crime, they clean up but they have nothing to do with it,” Sergi says.

Perre and his clan, she says, were never in the top tier. She says that if they are involved in the mafia they are part of the lower-ranked holdovers – older families but, unlike the gatekeepers, who have failed to evolve and adapt.

“An example of this category would be the Perre family in South Australia, even though their mafia status, clearer for Italian standards, has not been ascertained in Australia and should not be assumed,” she says.

But she says the characteristic of holdovers is that they failed to diversify their criminal interests.

McLaren says that his investigations showed without a doubt that Perre was involved in a major way and was a major player in the ’ndrangheta.

However, a third source who wanted to remain unnamed, says that a frustrated, lower-tier Perre often acted without the ’ndrangheta’s authority – but then reached out to them for help once he had done the deed.

This includes, they say, the 1994 NCA bombing.

Domenic Perre, 66, died at the Royal Adelaide Hospital of a heart attack last year, just seven months after being found guilty of the infamous domestic terrorism incident and while awaiting a decision on his appeal.

His legal team maintains his innocence in the 1994 bombing.

But today, there’s no doubt that the mafia life in Australia very much goes on without him.

Perhaps Perre’s prosecution shows that while a high-profile mafia conviction may not always make a huge impact to the ultimate power of Australia’s criminal underworld, which our fragmented police authorities have struggled to maintain, it can make a world of difference to the people whose lives were irrevocably damaged by them.

McLaren says that catching Perre got “a massive monkey off my back”.

He says that it wasn’t just his undercover work but “the whole South Australian Police Department” undertaking “investigations of a great standard”.

Bowen’s other son, Simon, who wasfive years old at the time, got the chance to stare Perre in the eye during prosecution and call him a “worthless human being”.

“You caused so much hurt, irreparable damage and suffering, all for what?” he said to Perre who sat listening with his eyes closed.

Spending his final years in jail, one wonders if Perre could satisfactorily answer that question – even to himself.

Simon and his brother are now proud and productive officers in the WA Police Force.

Upon hearing of Perre’s 2023 death, Geoffrey Bowen’s widow Jane Bowen-Sutton said that, “in death, he was known as a convicted murderer, that was enough for us.”

McLaren now lives in undisclosed isolation in New York State but his eye is always on the silent work of the Calabrian mafia, shadowy and agile, quietly becoming the most powerful crime group in the country.