Tina Namow shares the true horrors of living in a household plagued with violence

Tina Namow will never forget the moment her father threatened to kill her as a young girl but it was just one of many memories of violence that has triggered a career in helping other survivors.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When Tina Namow was 23 she held a knife to her father’s throat and threatened to slash it.

He had been a cruel, violent drunk who brutalised his family for years. That night, when he tried to hurt his youngest daughter again, she refused to take any more.

“There was a big knife in the sink and I put it to his throat and I said, ‘If you come near me I’ll kill you,’” Namow, now 75, tells SA Weekend.

“It was the most powerful event. For me it was liberating.”

It was also a full-circle moment. As a child, living with this volatile “mad man”, her mother and her older sister in a cramped caravan in the bush, the roles had been reversed.

“He would beat the crap out of us … punching, hitting against the wall. But the worst thing that stayed with me was when he put a knife to my throat when I was about seven and said ‘Will I, or won’t I?’”

As Namow tells me this story we are sitting in the small kitchen of her suburban Adelaide home. We are gathered around a bar heater for warmth but a chill runs down my spine.

A now-retired social worker, staunch feminist, mother and survivor, Namow has agreed to share the story of her life because she is “so concerned for this generation” of women and children who are still being victimised.

Over the past four decades she has drawn on her experiences to counsel other survivors of family violence, elder abuse and torture – and she has a message for those running a landmark royal commission into domestic and sexual violence in South Australia.

“I honestly believe it is worse now than I’ve ever seen it,” she says. “We have to stop making excuses. Enough is enough.”

Namow’s family migrated to Australia from the Netherlands when she was two years old. They lived in a caravan, drifting from one regional town to another in search of work.

“We had no electricity and running water for the first 10 years of my life. There was no escape in a two-berth caravan. Dad would rape Mum in front of us,” Namow says of her father, who died of a heart attack in the 1980s.

“Mum did everything for him because she was so terrified, but she couldn’t protect us. He always had a loaded gun in the caravan. He only had to look at it and that was enough to shut us up.”

If they ever called the police, back in the 1950s and ’60s, officers would advise them to let him sleep it off. “When they left we’d get a bigger hiding. The trouble is where do you go? We used to sleep out in the bush but Dad would track us down. He even hired men once with guns to try to find us.”

By the time Namow was 11 she had bounced between 14 different schools. She was skittish, painfully thin and had been admitted to hospital with symptoms of malnutrition. Eventually, she caught the attention of a social worker in the Victorian town of Geelong, where the family was living at the time. He visited their caravan and gave her mother a blunt ultimatum: protect your daughter or we’ll take her. “I owe my life to that social worker really,” Namow reflects, explaining that the warning finally convinced her mother to leave her abusive husband for good.

By this point, Namow’s older sister had left home to marry. Namow and her mother prepared to leave for months, squirrelling away possessions in her top bunk. When the time came, her mother sought work as a housemaid in nearby Melbourne but couldn’t find an employer who would allow her daughter to live with her. Namow was taken into state care, and it was nine months before they were reunited.

When Namow remembers the visitorto their caravan more than 60 years ago, she thinks that he might be the reason she became a social worker. Today she has “a filing cabinet full of cards” from grateful women and children she helped escaped abusive or dysfunctional homes.

They range from teenagers being tracked by an app on their boyfriend’s phone to women leaving marriages after decades of abuse and control. “One woman I worked with, it took her 43 years to leave him. It was total coercive control. It took her that long to save money. She was 70 when she left him and found peace,” Namow says.

One day, another woman arrived for a counselling session with Namow and minutes later there was a knock on the door. Her partner had tracked her to the building.

In a separate case an older woman confided that she was being surveilled by her husband in her own home. “He had cameras in every room. She wasn’t allowed to go out unless he was with her.”

At one point, the husband of another woman began stalking Namow after she helped his wife flee interstate. In the most disturbing case, Namow tells me she helped a woman who had been chained to her bed by her husband.

“She wasn’t allowed to leave the bedroom until he got home from work. Then one day he forgot to lock it and she came to me with chain marks on her ankles.”

Namow spent most of her career working in government-funded health and community centres in Adelaide, Alice Springs and Darwin, before retiring in 2019 at the age of 71.

Over that time, a lot has changed, and much is the same, Namow says. Factors like the national housing crisis and the persistent gender gap in retirement savings are trapping many women in abusive relationships – or forcing them into homelessness.

Namow tells me about one older woman “who was living in her car, with her walker and her dog, because she couldn’t stand it anymore”. “She said: ‘Tina, I can’t go anywhere (with family or friends) because he will kill them or threaten them.’ So she just travelled around to different parks.”

Women over the age of 55 are the fastest-growing homeless population in Australia.

Age Discrimination Commission research shows a third of women find themselves single by the time they reach retirement age and almost half of women aged 45 to 64 have less than $40,000 in superannuation. Minister for Seniors Nat Cook says that in half of reported elder abuse cases “the perpetrator is a relative of the victim”, including a mother-child relationship. This complexity meant it was “often an issue that is not spoken about”.

“Elder abuse really focuses on a relationship where there is an expectation of trust, and this trust is breached,” Cook says.

The state government-run Adult Safeguarding Unit receives more than 3000 reports each year about elder abuse in SA. Emotional abuse is the most common form (38 per cent), followed by financial abuse or exploitation (20 per cent). Amid the rising cost of living, more adult children are also returning to live with their parents and “they expect mum to provide like she used to, to do the washing, the cooking”, says Namow, who is an advocate for SA’s Council on the Ageing.

“If they’re having a hard time and not coping financially they might pressure mum to sell the house, or coerce her into a nursing home quicker than she wants. I’ve seen some just be absolutely abusive and controlling and use her money. I’ve seen (adult children) stand next to their mother at the ATM and threaten to beat her if she doesn’t get money out.”

Namow also worries about youngboys and girls entering into their first relationships, repeating the same harmful patterns she has been trying to disrupt her whole life. “It’s scary, because they’re saying the same things that I saw in the 1980s. But I do think the internet and pornography has made things worse.”

Namow left school at 15 and, when she fell pregnant in her 20s, was determined not to let her son become another victim – or perpetrator.

By the time he was 14 months old Namow separated from his father, who was struggling with deteriorating mental health, and raised their boy as a single mother.

Hung above his cot was a cartoon poster she hoped might subtly “brainwash” him, depicting men doing care work like changing nappies or washing dishes alongside women fixing furniture and mowing the lawn.

Namow put herself through university studying social work by day and washing dishes at night. In 1982, she met her now-husband John and the pair married two years later, but she was never going to take his surname.

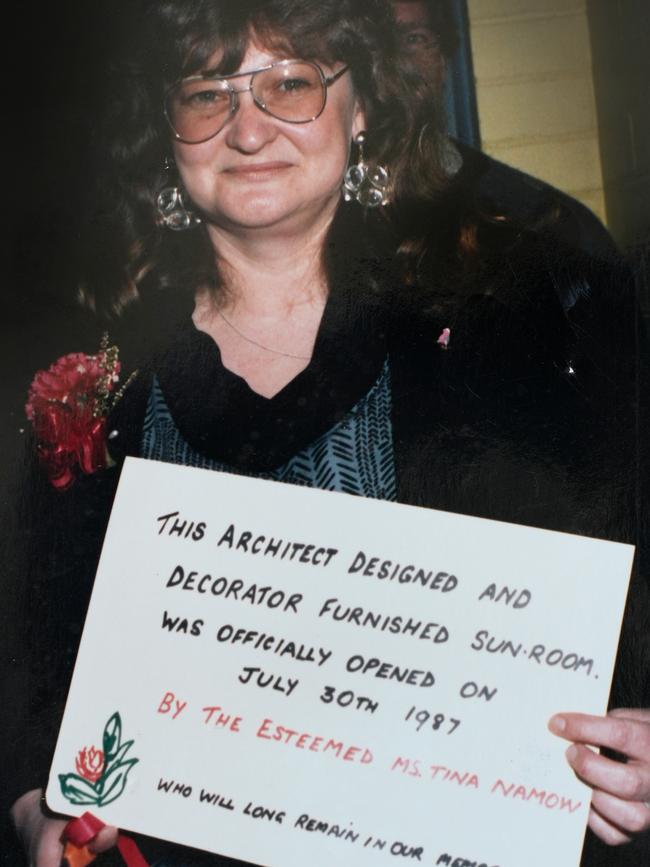

Namow is not Tina’s birth name. In 1975 she made the decision to legally change it because she was “so furious with all the men’s names” she had taken on over her life from her father to a series of troubled or abusive partners. If you haven’t noticed by now, Namow is Woman spelled backwards. “I’m proud to be a woman,” Namow tells me. “I guess I’m a strong woman.”

Given what she has shared, this would seem to be one of the greatest understatements I’ve heard in an interview.

At one point Namow was forced to escape a violent relationship where she lost a baby and almost died. She had met a “handsome, smooth man” and within three months they were living together. Once she was locked into the relationship, his jealousy and anger began to show. “He was so lovely until the day I moved in. Then he started being jealous of everything, if a man smiled at me … and the next thing I know I’m being pulled down the road by my hair.” Namow says the man, who we have not named for legal reasons, would beat and rape her “viciously”. She did find the courage to leave, fleeing to her sister’s house, but he tracked her down and threatened her family.

Feeling like she had no other choice, Namow returned. Eventually that “animal” beat her so badly she had to go to hospital, where she discovered that she had been pregnant but the baby had not survived the attack. “That’s when I thought, ‘You have got to have a better plan, you’ve got to get away’,” she says.

This cycle of abuse is extremely common in violent or controlling relationships, and often prompts outsiders to question “Why doesn’t she leave?” (rather than “Why doesn’t he stop?”).

Namow has worked with many women who have left and gone back multiple times, faced with threats to harm children or pets.

“This is what people don’t get when they say ‘Leave him’. Yes, you can leave but if they find you you’re not bloody safe. He can trace her, he can stalk her, he can do terrible things to her and still get away with it.”

Namow is infuriated that abusers are usually able to remain in their homes while “she has to run”. She has made a submission to the royal commission into domestic violence underway in SA, urging authorities to fund more home security devices for survivors, and to apply tougher penalties to perpetrators to deter reoffending.

And her message for all South Australians? “How do we want the world to be? It’s so great to see women speaking out now, but they have to have a hell of a lot of support. It’s time for people to stand up and say we will not tolerate this. No one deserves this way of life.” ■