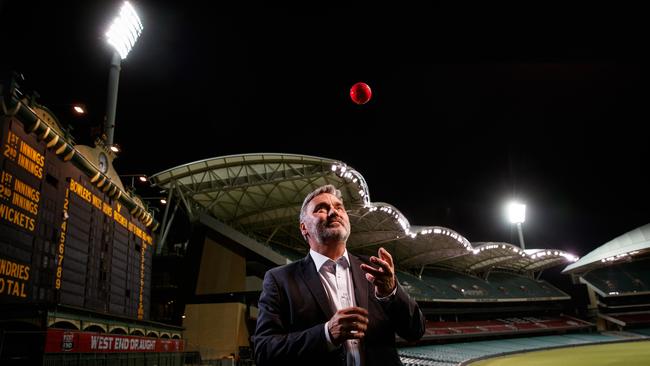

The unstoppable South Australian Cricket Association chief executive Keith Bradshaw

Keith Bradshaw played for Tassie, ran the MCC at Lords, revived Test cricket with day-night matches and a pink ball and now runs the SACA – and he’s done it all while battling a debilitating cancer. This is his remarkable story.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Australia v India 2020/21: Day-night Test push in Adelaide

- Adelaide Test: Adelaide Oval curator’s day-night pitch

Entertaining the Queen, kicking back with Boris Johnson, pouring the first drink for Daniel Radcliffe or reviving cricket – there are no boundaries for courageous trailblazer Keith Bradshaw.

Bradshaw won the hearts and minds of British society as Marylebone Cricket Club’s first Australian secretary from 2006-11 while championing innovation that made an ancient game new again.

This weekend Bradshaw, now South Australian Cricket Association chief executive, will watch with vindication as Adelaide’s fourth day-night Test unfolds between Australia and Pakistan. After all, he stared down critics who opposed his plans to reinvigorate cricket’s future with the introduction of day-night Tests.

He has also defied doctors who feared he wouldn’t live to see the pink-ball Tests when they diagnosed multiple myeloma, a cancer of blood plasma cells in the bone marrow, in 2008.

Bradshaw will take three fractured ribs and a depressed lung and spine into the day-night Test at Adelaide Oval.

Myeloma renders bones brittle but Bradshaw is buoyed by a blood cell count “that is coming down”.

“Just get on with it,” is the 56-year-old’s motto after completing a fourth 21-day cycle of chemotherapy to be cherry ripe for the Test.

“I have learnt to live with it,” he says.

“My feeling is, if I woke up in the morning and said, ‘I feel sick, I am not going to go work’, I would never come to work, that would be it. I just push through.”

It’s that same determination that has seen Bradshaw, the “Pink Ball Pioneer”, help reinvent and revive Test cricket.

Back in 2010 he orchestrated the landmark move of a traditional season-opening game between the County champion Durham and an MCC XI from Lord’s to Abu Dhabi where a pink ball was introduced under lights.

It was the critical forerunner to the pink-ball technology vital to the success of day-night Tests that are making cricket accessible to the masses again.

Scheduling Test matches at times – outside office hours – preferred by families, and in prime time valued by broadcasters, was for Bradshaw a “no-brainer”.

He was proved right when a non-Ashes record 123,000 fans attended cricket’s first day-night Test in 2015 at Adelaide Oval between Australia and New Zealand.

“I always saw day-night Tests as a way of reinvigorating Test cricket during a period where attendances were struggling in other parts of world,” Bradshaw said.

In a crucial endorsement, India and Bangladesh last week became the final Test nations to contest a day-night Test at Eden Gardens.

“It is really encouraging India are now making positive noises about day-night Test cricket through BCCI president Sourav Ganguly,” Bradshaw says.

Cricket finally has a pink ball that can be seen at night, and is also close in durability to the traditional red ball in Test conditions, that appeases reticent players and powerhouse India.

“That was work we started at the MCC in terms of developing the pink ball,” notes Bradshaw. “The challenge was to maintain the integrity of Test cricket, balance between bat and ball. I lobbied Cricket Australia, on arrival in Australia, to make sure we were positioned to hold a day-night Test.”

Adelaide’s cutting edge drop-in pitch – developed on Bradshaw’s watch with premier curator Damian Hough – is rated the best in the world and ideal for the pink ball.

“The expertise is there if the will is there,” he says. “People have voted with their feet.”

Bradshaw has a habit of making people see the light.

There seemed more chance of a Tasmanian tiger strolling through Salamanca Markets than the MCC establishment looking outside its gene pool for just its 11th chief executive/secretary since 1863.

Bradshaw’s path to that job was a strange one.

As a young man, any thought of being at Lord’s Cricket Ground would have been as a player – but he never made the Australian Test team.

A former Tasmanian all-rounder, Bradshaw jokes he’s “been helping SA cricket since struggling in a losing 1987 one-day grand final for Tasmania against David Hookes’s side in Launceston”.

That was a time, Bradshaw reminisces, “before ice baths, when post-match recovery was David Boon chucking a couple of cans out of the freezer”.

Faced with providing for a young family or pursuing his Test “dream”, Bradshaw retired, aged 25, after 25 first-class games.

“I was working in a bar job, stacking bricks. At that point I had a childhood sweetheart and we were thinking about getting married,” says the father to Eliza, Donald, Juliet and Jack.

“It was a case of go back to university and get a job or keep playing cricket. I made a decision, there just wasn’t the money in the game. I wanted to play for Australia but also wanted to have kids and a family. I studied part-time for 10 years, which was really hard to be honest, and became a chartered accountant.”

Bradshaw was a partner at accounting firm Deloitte in Hobart when the phone rang with the offer that was to change his life.

Asked to apply for the MCC post in 2005, Bradshaw couldn’t understand the fuss over relocating to Melbourne when it was just an hour’s flight from Hobart.

“The head hunter said ‘not the Melbourne Cricket Club, it’s the Marylebone Cricket Club’,” recalls Bradshaw.

“I picked up the phone to Denis Rogers who had been a Cricket Australia chairman and asked him to mentor me. He did so on the condition that I would proceed on the basis I would never get the job because I wasn’t a Brit.”

The MCC, founded in 1787 and custodian of cricket’s laws, had been superseded in relevance by the Dubai-based International Cricket Council.

The MCC privately conceded it needed a makeover but finding a progressive candidate steeped in the game’s rituals was difficult – if not counterintuitive.

After eight telephone interviews in five months, Bradshaw made a four-person shortlist that was asked to deliver 11-minute presentations in London.

“There was a lot of media speculation over who the shortlist was, so it was done in a secret hotel in Mayfair,” Bradshaw says.

“I differentiated myself from everyone else; didn’t do a power-point. I just went in and did it. Halfway through a waiter came in and started to serve coffee. I stopped him and served the coffee to the panel.”

Bradshaw’s Australian sense of egalitarianism told more than a million words could.

“I was having dinner. They rang me and said, ‘We would like to make you an offer’. I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “Part of my appointment, and I think that was one of the successes, was someone who could break down the barriers.”

Former MCC president and journalist Christopher Martin-Jenkins acknowledged “the last bastion had been crossed” by a Tasmanian who paraded an impressive 1980s mullet during a larrikin David Boon era.

Bestowed the keys to Lord’s, Bradshaw, as MCC secretary, was a world away from that “subsistence living” playing for Tasmania.

Bradshaw was in paradise, waking up in his Lord’s cottage to cricket’s premier theatre, lush lawns and the famous Father Time weathervane in the distance.

“It was definitely a culture shock,” he says. “The job itself, living behind the pavilion at Lord’s, people you meet, having an office that looked out over the hallowed turf. It was such a privilege.”

Bradshaw had viewed MCC “as a supertanker going through the ocean, a little click here and there” – but that was about to change.

Pakistan’s 2006 fourth Test forfeit at The Oval unfolded the day Bradshaw touched down in London to take up his role. Pakistan walked off the field on the fourth day after umpires Darrell Hair and Billy Doctrove ruled Pakistan had ball tampered.

The absence of MCC comment and direction on the issue highlighted a retreat from primacy.

“When I arrived I had this perception that at one point the MCC ran the game, and were almost becoming irrelevant. It did seem they should become more vocal …” he recalls.

“Tony Lewis was the chair then and bought into things like the Steve Waugh anti-corruption lie detector test. We started making public pronouncements and I guess the danger was people weren’t even asking the MCC about issues. We got to a point where the MCC was being asked to comment, making them relevant and putting them on the world stage again.”

If the MCC was in danger of becoming obsolete off-field, Lord’s absence of floodlights threatened to cost it vital revenue.

Bradshaw took on residents and politicians to enable the installation of lights that were used in the 2009 World Twenty20.

England’s new 100-ball competition The Hundred, to start next year featuring eight teams, is a by-product of Bradshaw’s vision to introduce a limited overs tournament with fewer than half of the 18 County teams.

Bradshaw successfully campaigned as MCC boss to end an insidious competitive bidding process between County associations that saw them paying the England Cricket Board $1.9 million to stage a Test.

Financial ruin for the domestic game was thwarted.

But a residential development pushed by Bradshaw that would have generated $190 million proved a bridge too far for the MCC purists who opted for a scaled back $95 million upgrade of stands.

“I challenged some of the norms in terms of making Lord’s accessible to the public,” says Bradshaw who would later oversee a $575 million Adelaide Oval redevelopment.

Princess Mary of Denmark was the closest Bradshaw came to royalty growing up in Hobart. Connecting with Elizabeth II encapsulated “pinch yourself” moments that became customary at Lord’s.

“Hosted the Queen several times,” he says.

“Had a couple of private audiences. You greet, bring into the pavilion and introduce her. She is incredible, amazing and showed a real interest when she came to the Ashes.

“Her visits in terms of security are down to the microsecond but she enjoyed the Ashes so much she stayed longer at the game. She would circulate, stayed for lunch one day and was delightful. Prince Philip spent a lot of time there as well.”

Bradshaw’s contact book started to rival Buckingham Palace’s social directory.

Johnson, now the Queen’s incorrigible Prime Minister, was an electric presence. “Boris was effervescent, really good fun, really engaging. He had some terrible cricket stories about his performances. He wasn’t a great cricketer but made fun of himself.”

There would be days with Hollywood director Sam Mendes and Academy award-winning actor Goldie Hawn, while Mick Jagger “loved his cricket, liked to sit and watch”.

“I am still in contact with people like Stephen Fry and Michael Parkinson as they are just really good people,” says Bradshaw, who is also close to debonair former England skipper David Gower.

There were a few embarrassing moments, like when he was oblivious to Kirsten Dunst’s celebrity – or her boyfriend and Razorlight lead singer Johnny Borrell.

They would become firm chums after Bradshaw finally twigged that Borrell was the frontman for the band dominating his iPod while Dunst was starring in Spider-Man.

“They came up to the box and Johnny Borrell and I became really good friends and he ended up playing in my farewell match. The funny thing with Johnny was he trained and trained, and got out second ball,” Bradshaw chuckles.

It was Daniel Radcliffe who shared a coming of age moment in the MCC box with Bradshaw.

“I think I gave Harry Potter, Daniel Radcliffe, his first legal drink,” he says with a mischievous grin.

“He came on his 18th birthday. I said, ‘Can I give you your first legal drink then?’. It was a Veuve [Clicquot], which I couldn’t participate in as I had an alcohol ban for staff.”

While Bradshaw surprised the best of Eton and Oxford for the plum Lord’s role, his authenticity as a people person commanded immense loyalty from staff.

“While I am lucky, people say, that I have a really good contact book, it is about treating everybody the same,” he says.

“I remember at Lord’s you would talk to the gateman or cleaner and the chairman would say, ‘How do you know everyone’s names?’. I would say, ‘They are my part of my family here’. When I first arrived they would call me Mr Bradshaw and I would say, ‘No, that is my Dad – it’s Keith’.”

It’s easy to move with Mick Jagger and the famous but few bother to bring castaways in from the cold.

“When I first arrived, Michael [Parkinson] was always sitting in a corporate box away on the other side of the ground from the MCC box. It was said he hated the MCC so we don’t invite him,” says Bradshaw of the acclaimed interviewer.

“I said, ‘Why not?’ I went around to him and he came one day. From that moment on he loved it and would come every year with his wife.”

Son of a coal miner Parkinson and Bradshaw had much in “common” in a country stratified to its boots.

“Cricket brings people together whatever their standing,” says Bradshaw, who struck a ton in his fifth first-class match against Queensland.

Bradshaw’s time at Hobart’s only boys’ public school was a redeeming feature for the Lord’s old guard – to the Tasmanian’s amusement.

Public school status is different in Australia but it afforded New Town High graduate Bradshaw empathy for outsiders.

Jeffrey Archer was another one. He’d been given a seven-year suspension from MCC membership after being jailed for perjury resulting from a 1987 libel trial.

Having served his punishment, Bradshaw believed the best-selling author deserved a second chance.

“Jeffrey Archer’s membership was put in abeyance,” he confirms.

“I had seen him after he got out of prison and he revealed the MCC had stopped inviting him. I said he could come in my box. ‘Who invited him?’ somebody queried, and I said, ‘I did’.”

An inconspicuous, wooden door in a wall located in the coronation garden leads into the chief executive’s house at Lord’s.

Indian superstar Sachin Tendulkar was part of the furniture at Bradshaw’s St John’s Wood abode – initially through necessity, then affinity.

“We would chat. Sachin had the PIN number for my big security gates and driveway at Lord’s so when he wasn’t playing or wanted to come to the cricket he would text me,” says Bradshaw.

“He would pop the PIN code in, park in the driveway, come through my house and I would meet him at the back with about six security guards, form a circle around him, and walk him to the box and back.

“The funny part was one day, I was away and my stepdaughter Maddie rang me and said, ‘I am just letting you know that man has arrived again, but don’t worry I have made him wait outside!’ I still laugh about it.”

Regrettably, the grandeur of the world’s oldest sports ground made it a symbolic target. Bradshaw became familiar with London’s top police brass and spooks. The longest 10 minutes of Bradshaw’s life came during a terror threat that put Lord’s in lockdown.

“There was a car parked in the vicinity of the ground that we couldn’t validate for about 10 minutes during a sweep,” says Bradshaw. “That was causing us some problems. It was huge, really stressful.”

An unrelenting burden fell on Bradshaw to ensure cricket’s genteel home wouldn’t turn into a killing field.

“Bomb scares could be quite nerve-racking in the control room when there has been a call,” he admits.

The 2010 Pakistan match fixing scandal that unfolded at Lord’s saw Bradshaw become integral to a police investigation, then safeguarding the lives of player suspects.

A sting from the now defunct News of the World would reveal Pakistan captain Salman Butt and bowlers Mohammad Asif and Mohammad Amir had agreed to underperform at designated times during the fourth Test, in collusion with a sports agent and underworld figures.

“Four detectives from the Metropolitan Police, including the deputy commissioner, came to my office,” says Bradshaw.

“There were three players on the field they wanted to interview but didn’t want them to get their phones back.”

Plain clothes police had lost a fourth suspect in London meaning Bradshaw had to buy time for police to detain the Pakistan trio in the dressing-rooms.

“I called a (false) security threat after play so the players had to stay in their dressing-room and couldn’t get their phones. I got served a warrant at 11pm, let the police into the dressing-rooms, and the plain clothes police did what they needed to do. The next morning the story broke. We didn’t know if the Pakistan team would turn up to play.

“There was concern the amount of money involved posed a security risk to the players and someone would try and take them out. The batsmen going out to bat were escorted by armed security and we had the post-match presentation in the long room.”

Confronting a 200-year orthodoxy at Lord’s demanded an unflinching long-term commitment, which Bradshaw couldn’t give as his family and health deteriorated in 2011. “My father in Hobart had gone into a nursing home, was very unwell,” says Bradshaw, whose youngest son Jack is on the autism spectrum.

“My mother looked after my younger brother Antony who has special needs. She passed away unexpectedly and I didn’t get back to see her in time. I decided I better come back to Australia and resigned.”

Bradshaw returned to Australia after accepting SACA’s chief executive role in 2012 – but so did a cruel cancer. Stem cell transplants and heavy chemotherapy meant Bradshaw was in hospital for weeks while MCC boss. He was rendered bald and unrecognisable to the Lord’s doorman.

Determined that chemotherapy won’t interrupt his daily routine in Adelaide, Bradshaw takes on the fight from desk to door regardless of debilitating side-effects.

“There are services where you have chemo at home. I would also sneak off to the work first aid room when I was having it intravenously so nobody sees,” he says. “I can still come to work. There are days I don’t feel well and in quite a bit of pain at the moment but I feel so lucky.

“There are so many people that are worse off. I have a really good team at SACA, support from the board and my partner Helen is just so incredible. The cancer becomes immune to the chemotherapies. There is no cure for it but you hope they keep finding ways of maintaining it.

“There’s a group of people that have myeloma that live 20 or 30 years and I put myself in that batch. I have been going 11 and hopefully there might be a cure come up.”

Bradshaw’s thoughts, despite his predicament, are for others – particularly late Test batsman Phillip Hughes.

He did everything possible to hold devastated SA teammates together as Hughes succumbed to a head blow while batting against NSW on November 25, 2014.

Bradshaw pauses this interview twice. Pain shooting through a metal hip forces him to jolt upright to shake off cramp but Bradshaw’s face provides no hint of the battle inside.

It takes memories of Hughes’ last night to force a tear. “He’s still ever present for me and people here,” he says. “That was the hardest situation that I have ever had to deal with. I spoke to the doctor and agreed we should prepare the playing group for the fact Phillip may not make it through the next 24 hours, which very sadly he didn’t. We had set up a room where they could all go with their families and support people but to go up there and tell them, it was awful.”

No-one has beaten myeloma but Bradshaw is giving life a good shake. Daughter Juliet will marry in Brisbane in 2020 while there’s unfinished business in the boardroom.

The first place to host a day-night Test, Adelaide deserves to be the venue for powerhouse India’s first pink ball match in Australia next year, he argues. “We are the second highest attended Test in the country after the MCG and highest per capita.”

Bradshaw is planning a landmark Peace at the Crease charity match next year where legends Tendulkar, Brian Lara, Ricky Ponting and Muttiah Muralitharan would front. The Twenty20 clash featuring Tendulkar’s Mumbai Indians could attract around 300 million viewers and cash for 2019’s bushfire victims.

“I love innovation in the game, think the game is changing rapidly and we need to keep pace,” Bradshaw says. “Being in Adelaide doesn’t mean we have to be an imitator, we can be an innovator. Initiatives like Peace at the Crease can put Adelaide on the global map.”

It’s the sort of opportunity that keeps him excited. “I feel like I need to keep going and don’t want to sit back and be a wall flower,” he says. “There are a lot of things happening here. From my side I will never give up.”