The South Aussie hoax that won’t die

It was 1944, and the place was Adelaide when Max Harris fell victim to the notorious Ern Malley literary hoax — it was the first step in the pornography trial riveted an entire nation.

This is a story with no beginning or end.

So let’s start at 3am on a cold Adelaide morning in 1944. Max Harris is asleep, his phone rings, he reaches over and Colin Simpson, a journalist from Sydney’s The Sun, says, “Max Harris?” Harris stirs, mumbles a few words, and Simpson says, “Turns out there was no Ern Malley.”

“Sorry?”

“The poems. No such person. They were written by a couple of poets called McAuley and Stewart.”

Harris sits up, demands an explanation, and there follows the rest of his life, in a sense.

Jump seventy-five years and I’m invited into Samela Harris’s cottage. The hallways are lined with “Maxobilia” – paintings, newspaper cartoons, photographs and tributes to Harris – small testaments to a man Samela describes as “glowing, handsome, exquisitely beautiful, wild, articulate, a prodigy in so many ways, constantly reading, never forgetting, a bit of an erudition show pony.”

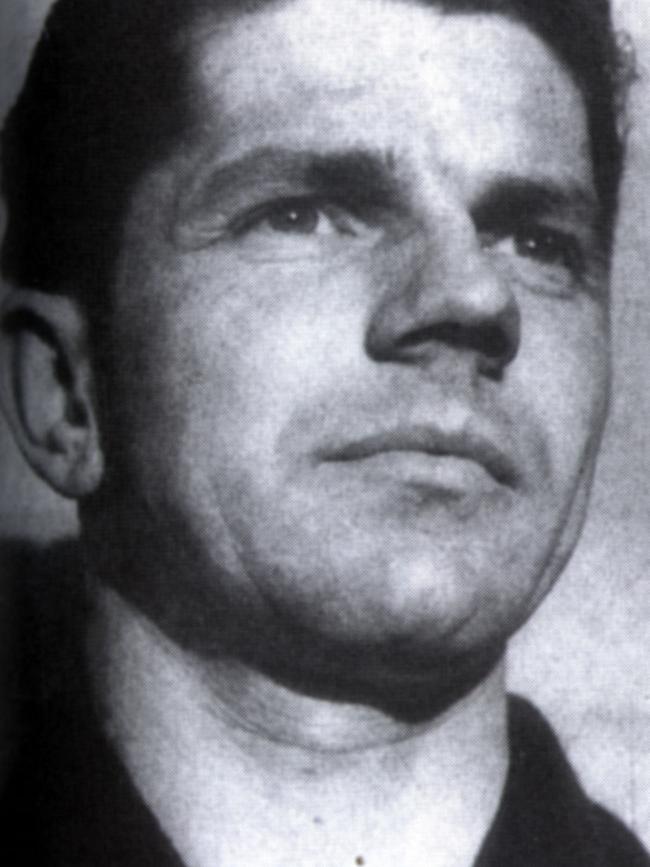

Max Henley Harris (1921-1995) was an Adelaide (via Mount Gambier) original.

Poet, novelist, Rupert Murdoch’s favourite columnist on The Australian, but, more importantly, the man who gave us Ern Malley and his sister, Ethel.

He was Victor Frankenstein, breathing life into a story, a myth that has outlived everyone involved in its making, the thousands of words written in literary defence, in criticism, in poems and novels, songs and renowned art works by Sidney Nolan, Garry Shead and others.

But, more importantly, in the spotlight of history, Harris was the man who stood up in the Supreme Court of South Australia to defend his right to publish, Ern’s right to scribble and, today, by extension, our right to think and say what we like.

He took on what he called “the tight and vicious little world of Adelaide in the 1940s”.

Harris’s daughter Samela shows me original paintings by the who’s who of the modernist Adelaide art world of the era: Ivor Francis, Dave Dallwitz, George Williams.

“There’s a lot of Max around here.” He lingers in the overfull bookcases (“Max read the Mount Gambier Library from the kids’ books to the plumbing section – a to z”), his chocolate brown oil painting eyes following you around the room.

Outside, in a white-walled courtyard, vivid flowers reach for the sunlight as I set out to explore the hoax, the trial, the complex man behind it all. Someone who, in Paris or London, might have found fame, or at least understanding, but instead, chose to live most of his life in Adelaide.

Even on its 75th anniversary, it’s a sensational story yearning to be told.

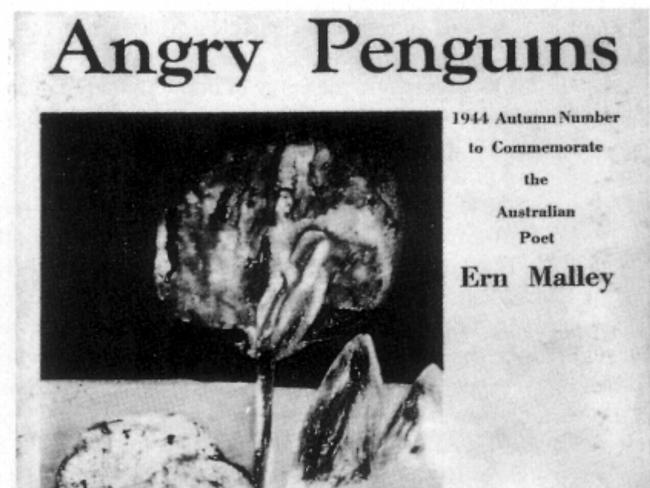

In early 1944, Harris was the co-founder with fellow University poet progressives Sam Kerr and Paul Pfeiffer of a new Adelaide-based modernist publication called Angry Penguins.

He and other supporters had set out to upset the delicate balance of Australian arts – Gwen Meredith’s Blue Hills on the wireless, the influential Jindyworobak poetic movement’s emphatic impetus on pastoral poetry, Christopher Brennan’s neoclassical verse.

All of it was so colonially-insulated from the artistic and intellectual innovations that Harris saw going on in Europe – the new life forces of James Joyce, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, of Giorgio de Chirico.

Then, one day, Harris received a letter from a woman in Sydney: “I was going through my brother’s [Ern’s] things after his death [when] I found some poetry he had written.”

Ethel Malley had sent two of her brother’s poems, one of which was Durer: Innsbruck 1495.

I had often,

Cowled in the slumberous heavy air, closed my inanimate lids to find it real …

Harris was taken by the newness, the riskiness of the poems. Ern was an Australian T.S. Eliot, his work perfectly formed, unpredictable, unlike anything else in the country.

Harris wrote back to Ethel asking to see the rest of the poems and, in due course, he received the collection called T he Darkening Ecliptic.

The poems were eventually published in the autumn 1944 number of Angry Penguins. Not long after, Harris later explained, “a suspicion arose that the poems were not genuine”.

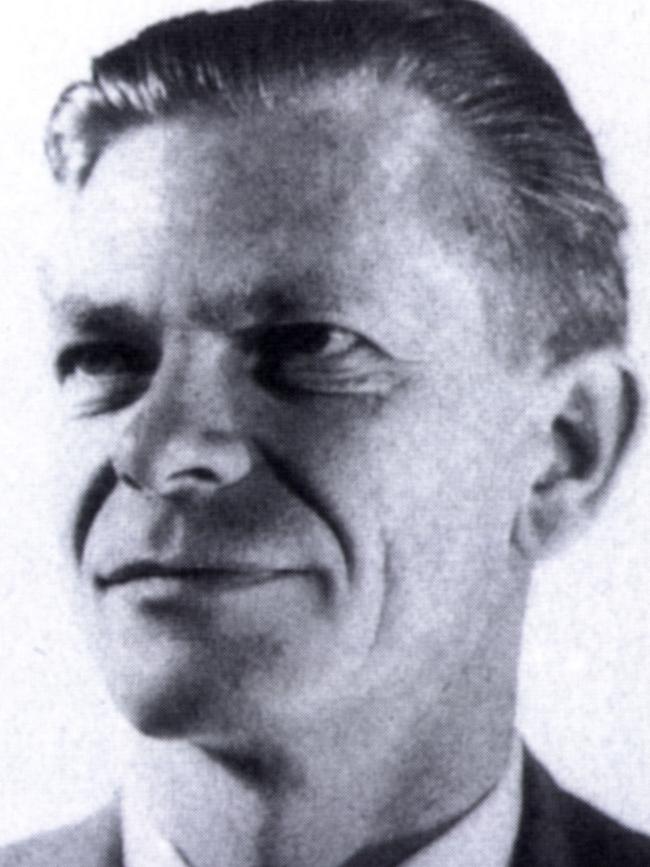

Foremost among the doubters was Brian Elliott, Lecturer in Australian Literature at University of Adelaide. There followed the 3am phone call and, soon after, a statement published in the S ydney Fact: “We [Harold Stewart and James McAuley] decided to carry out a serious literary experiment. There was no feeling of personal malice directed against Mr Max Harris.”

McAuley and Stewart were minor poets – soldiers, based at Victoria Barracks in Sydney – highly suspicious of modernist poetry. Harris later said, “McAuley and Stewart were poets of real sensibility, but totally committed to traditional verse forms.” It was this distrust of anything new, experimental, that led them to Max Harris, who they saw as a poseur.

Harris, apparently, had to be done over, to be shown up by McAuley and Stewart. They were egged on by establishment poet A.D. Hope, who had a real grudge against the young, outspoken progressive Harris, and his celebration of surrealism and modern European trends.

And so came to pass that two mischievous young soldiers contrived the world’s now most celebrated non-existent poet, Ern Malley.

Despite the fallout over the next few months, years, Samela explains that “Max defended Ern Malley to his last breath”. According to McAuley and Stewart, the poems were nonsense, thrown together from random lines of John Keats, a textbook on tropical hygiene, anything to hand. Regardless, Harris saw the poems then, and after, as having high literary merit.

Anyway, what was good or bad? Wasn’t it just someone’s opinion? Harris dug in his heels. According to Samela: “Max really wanted the visual arts and modernists represented together to overcome the pastoral stodginess of that era that did not want to be budged.”

But things were about to get a lot tougher for Harris.

On Tuesday, August 1, 1944, Harris was busy at work in his shoebox-sized Grenfell St office. Just after three, two policemen entered. Detective Inspector Jacobus Andries Vogelsang said: “We are police officers. What is your name?”

Harris told them, and Vogelsang said, “We have been instructed to make inquiries in connection with provisions of the Police Act with respect to immoral or indecent publications.”

The complaint had been signed by Crown Solicitor Tacky Hannan and identified 13 Penguins’ passages the Crown “found offensive”. Not just Ern Malley, but other contributors such as Peter Cowan, Dal Stivens and Laurence Collinson.

So began the second act of the Ern Malley saga. Harris, still recovering from his syndicated embarrassment, was accused of publishing what the South Australian police claimed amounted to pornography. As Samela tells me: “He was hideously vilified. People spat at my mother in the street.”

The trial was national and international news. The tabloids dined out on it. It made Adelaide, and South Australia, look like a cultural and intellectual backwater. And there’s Harris, at the eye of the storm, asked to justify his editorial choices. He later said, “The South Australian police had decided that seven poems by Ern Malley were ‘indecent advertisements’ and seven other items in that issue of Angry Penguins were also either ‘indecent, immoral or obscene’.”

Of course, Harris wasn’t alone.

Lawson Glassop’s We Were the Rats had recently been banned in Sydney, Love Me Sailor was the centre of a Victorian prosecution and William Dobell was defending his Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Joshua Smith in a Sydney courtroom. This was still wowser-Australia; conservative, religious, keep-it-away-from-the-kids Australia. Art certainly had a place, but only within accepted cultural constraints.

The trial began on September 5, 1944, in the Adelaide Police Court. The national media swarmed. The small, bryl-creamed city of fewer than half a million people gathered around radios, studied newspapers and waited for a glimpse of the key players. Harris believed that “the impression of the trial was one of one section of the community engaging in a vendetta against the other”. Old versus new. Establishment versus progressive modernists.

Samela explains that her father was intent upon “defending the poems … line by bloody line”. He was determined to take on the Adelaide philistines, from the University of Adelaide science students who’d thrown him into the Torrens, to the Adelaide Establishment. Harris thought there was more to the trial than the police deciding it was obscene material. Why were they interested in the first place?

He always thought his history as a young communist with his university chum Mary Martin was one element, but also, he believed his membership of Melbourne’s famous Left wing Heide arts enclave played a part. Its doyen, Sidney Nolan’s lover and patron Sunday Reed, was the black sheep of and embarrassment to the powerful Victorian Baillieu political dynasty. In other words, the Melbourne Establishment disapproved profoundly of the “little como enclave of arty-fartys”.

According to Michael Heyward, author of The Ern Malley Affair, Harris also believed “the case derived directly from the personal actions of Tacky Hannan.” Harris later said: “It is quite certain Catholic Action is the guiding force.”

Whatever the reason, Harris believed the prosecution was ludicrous. Take, for example, the apparently indecent poem, Night Piece, in which iron birds splash

… white foam in the dark!

And you lay sobbing then,

Upon my trembling intuitive arm.

Or Sweet William, in which (Harris later explained) Vogelsang “did not object to any individual reference … but to the poem as a whole”.

And I must go with stone feet

Down the staircase of flesh

To where in a shuddering embrace

My toppling opposites commit

The obscene, the unforgivable rape.

Vogelsang attempted to critique this poem by saying, “I consider it is immoral, the struggling against temptation and yielding to temptation is immoral.”

According to Samela, “Max was fatalistic. He was too intelligent to invest a great deal of personal bitterness and emotion [into the trial].” Also, “he put a lot of faith into the international literary opinions that came to defend him in the case. Sir Herbert Read, for instance, world expert in modernist art and literature. To Max, this echelon of support was what mattered in the big scheme of things. So he just took it on the chin. Never to imagine that it would go on and on and on.”

As it did, until the sunny June day that I sat with Samela Harris, still determined to help people understand the man who, from her earliest days, cast too big a shadow. “Every time I did a good essay at school they’d say, ‘your father helped you with that’.” From school, to law, to journalism, Samela Harris was at the forefront of women in the media. Arts, sport, books, theatre, the lot. The first female journalist employed by The News in 1965, all the time, determined to become more than just Harris’s daughter.

But now, she explains, “I’ve got to keep that flame. Max was such an outspoken public figure on so many levels for so long. He spoke to both the highbrow and the lowbrow. He was a true Everyman.”

Meanwhile, back in court, Harris was busy doing what he did best. “Dutchy” Vogelsang started with a question about Sweet William. “What is the theme of the poem?” Harris replied, “I do not know what the author intended by that poem. You had better ask him what he meant.” Vogelsang got hot under his collar. “What do you think it means?” Harris replied, “I am not going to express an opinion.”

Moving on to Boult to Marina:

Lady of these coasts,

Blown lily, surplice and stole of Mytilene,

You shall rest snug tonight and know what I mean.

Vogelsang explained: “‘… shall rest snug and know what he means’ is indecent … It offends my decency to suggest that a character means he wants sexual intercourse.” More verbal jousting followed, with Harris saying, “If you are looking for that sort of thing, I can refer you to plenty of books and cheaper publications that you can fill your department with.”

It was a scene straight out of a yet-to-be-made film, something verging on the absurd, as Harris was forced to defend his enemies’ fake poems, even at the slightest hint of ribald (Part of me remains, wench, Boult-upright).

Harris believed “the whole aim of the Crown Prosecutor was to prevent any logical sequence of expert opinion being put forward uninterruptedly. For example, in the evidence of Dr R.S. Ellery the transcript records seven objections in the course of 10 questions”. Professor Stewart faced 10 objections, Dr Brian Elliott, three.

Making the judge’s final verdict (Max choosing to pay a £5 fine over 12 weeks jail) almost pre-determined. As Harris explained, “as the law was framed at that stage in South Australia, literary merit … in no way constituted a defence. Had the Crown Solicitor’s Office chosen to prosecute the works of Shakespeare or the Holy Bible, a magistrate would have had little choice but to have found these works guilty of indecency, immorality or obscenity”.

It is a battle that’s been going on forever. Someone claiming our planet was actually round; Galileo locked away for insisting the Earth revolved around the sun; Dmitri Shostakovich made to justify his music to Stalin; German author Ernst Haffner summoned to Goebbels’ office to explain his novel Street Kids (no one saw him again after that). It prompts the question, what really defines a “small” city? Harris said later “… the movement [modernism] produced partisan feelings even in people who knew nothing and cared nothing about literature, modern or otherwise”.

The key players in the “Ern Malley affair” went on to varying degrees of success. James McAuley converted to Roman Catholicism, co-founded (and edited) the conservative journal Quadrant and, from 1961, was Professor of English at the University of Tasmania. Harold Stewart also converted, to Shin Buddhism, moved to Japan in 1966 and wrote and translated poetry. Harris didn’t let the grass grow under his feet, running a bookshop with Mary Martin and, after her move to India, expanding the chain across Australia. He pioneered the remaindered book industry, founded and coedited Australian Book Review, worked as a News Limited columnist and, for obvious reasons, wrote widely and passionately against censorship.

Now, 75 years later, perhaps it’s time to cast our minds back to those days in 1944, the world divided by ideologies, at home and abroad. To ask who we are, what we value, why we believe what’s dished up by mass media in an age of fake news, Twitter and opera-hating columnists.

To return to 3am on that cold morning in 1944, Harris learning he’d been had, but simply saying to Colin Simpson, “The myth is sometimes greater than its creators.” As it was for Ern, Ethel, Harris, Vogelsang, and the poems that stubbornly refuse to go away.