Sonya Ryan and her fight for Carly’s Law

TEN years ago, Sonya Ryan’s heart broke when her daughter Carly was murdered by a paedophile she met online. But love for her child brought the SA mother back from the brink and inspired her to fight to protect other children.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Sonya Ryan’s cyber crusade goes global

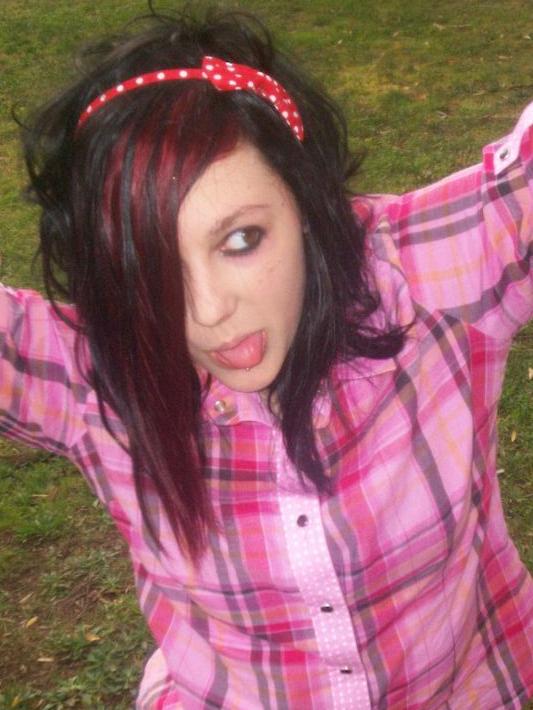

- Carly Ryan: The loving girl who fell victim to an online predator

IT is a decade since Sonya Ryan began the day as a worried mum who could not raise her daughter after a sleepover. Later that morning, she became a mother in panic who found an empty house where Carly was meant to be. Panic changed to something much worse after a stranger rang to say he had found Carly’s purse, miles from where she should have been.

“I knew right then that something was wrong,” says Ryan. “Why was her purse by the side of the road at Chandlers Hill? I immediately rang Missing Persons.”

Ryan didn’t know it but by then Carly’s lifeless body had already been found, early in the morning at Port Elliot, half covered in sand, by a nurse walking her dog. Later that afternoon, the police came to the house in Stirling to talk about the Missing Persons report, but they wouldn’t leave.

“I thought that was unusual that they wouldn’t go,” she says. “They hung around and hung around, and then detectives walked in the door and one of the police had tears streaming down his face.”

Still, your mind doesn’t go to murder, how could it? She thought there had been an accident and hoped for the best, for something recoverable. So when they said ‘Sit down, we need to tell you we’ve found a body that matches the description of your daughter, at Port Elliot’ the words didn’t even make sense. Her mind could not comprehend that this was real.

“It’s almost like entering a movie, you’re watching everything unfold around you; you disassociate,” Ryan says. “I think it’s the mind’s way of protecting you from literally having a heart attack on the spot and dying.”

Much has changed since then and along the way Ryan has found a kind of salvation in honouring her daughter with a federal law in Carly’s name. This was a personal high, as was becoming 2013 South Australian of the Year for her dedication to the promotion of internet safety.

But back then, aged 36, she was a young mother who Carly’s friends envied because she had a cool factor that their mothers didn’t. Ryan had a vampish MySpace profile and her daughter was more of a best friend. In February 2007, she was hurled into the worst horror imaginable that included the next morning identifying her daughter’s beaten and dumped body. That remains too harrowing to talk about.

“It was a succession of horror,” she says. “Not just the fact that she had been killed brutally by somebody, but that all of the coroner’s processes and the investigation and everything were utterly horrific. I got pulled into this blackness that (Carly’s murderer) Garry Newman created.”

You imagine grief as excruciatingly mental anguish but it’s the physical effects that make the suffering almost unendurable. Her family arrived and they were feeling the same; her sisters shuddering with the horror at what had befallen a happy young girl with an exceptionally sunny nature who was the light of their lives. At 15, she still played cubbies with her younger brother and a few nights earlier had sat up in bed reading bedtime stories to her niece. Now this.

“I thought I was going to die at any moment,” Ryan says. “Everything shut down. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t function, I couldn’t sleep, I’d be pacing all the time. It was such devastation I didn’t think I was going to make it.” She had enough clarity to realise she needed help and found a physiotherapist in Mt Barker who she says pretty much saved her life. He would treat her body to stop the shaking and the nervous tremors. She sought emotional help from counsellors but the first few gave up.

“They couldn’t cope with what they were seeing unfolding in front of them,” she says. “I had three or four counsellors saying ‘I can’t, this is too much for me’. They just walked away.”

Then one counsellor stepped in and started to explain what was going on, that her body’s defence mechanisms were in full flight and while it felt unpleasant, it was a natural response to major trauma. Mentally she was in an almost purified state as grief dissolved the layers of her everyday personality and the life she knew fell away.

Doctors offered to ease her distress with drugs; sedatives, antidepressants, sleeping tablets, but she refused them all. She can’t explain exactly why but she felt that if she started relying on drugs to get through, she would be lost.

“I just wanted someone to put me in a coma and leave me there for a few months,” she says. “The fact that I am sitting here in front of you, still sane and alive, is a miracle.”

Ask what happened to bring her out of the darkness and towards the light and the answer is Carly. She began to focus on their love connection and the realisation that their bond was not severed now Carly was gone. Without wanting to sound nuts, she began to feel her daughter’s presence and it brought her enormous comfort to know that Carly’s murderer had not destroyed the love along with everything else. Their connection stayed as strong as it ever was and — slowly — it saved her.

“That pulled me out of the blackness and into some kind of light,” Ryan says. “I focused on her and what she would want me to do in this annihilation. I kept focusing on how much I loved her and adored her.”

This became her lifeline and it pulled her out of the netherworld into which Carly’s murderer had thrown her. She became purposeful, fuelled by the desire to prevent a repeat of what were then the rare circumstances of her daughter’s grooming online by a murderous paedophile.

Ryan had been just an ordinary woman who liked being around people and worked at various jobs including staff training and real estate. There was nothing special about her; she was a separated mother of Carly, 15, and a son who was 10 when it happened. She thought about normal stuff, like work and her kids, her family and having a bit of fun. Now her mind turned to how naive it was to think that Garry Newman was the only creep out there trawling the internet for victims. The power they could exert over an innocent terrified her.

Newman, 50, had 200 fake identities and he spent 18 months grooming Carly by pretending to be Brandon Kane, a 20-year-old musician from Texas, who lived in Melbourne. He played guitar, so he said, and told Carly she was hot, which to a girl of 14 seemed like a dream come true. She was like a giddy teenager in love, happy and excited to have met such a boy.

On February 19, 2007, Newman duped Carly into thinking she was to finally meet Brandon at Victor Harbor. As a cover, she told her mother she was staying overnight with friends. There was nothing unusual in that and she slept over at friend’s houses often. Nothing seemed amiss.

“These people have a tunnel-vision focus to harm and it’s hard for the public to recognise that because it rocks their own world and their safety,” Ryan says. “Even with Carly there was victim blaming: ‘Why did she meet him?’ ‘Why didn’t she tell her mum?’ Because she was groomed, because she was manipulated, because she was a child.”

Ryan’s thoughts congregated around the idea of taking steps to stop groomers in their tracks. Carly had been wooed using MSN messaging and MySpace but new pathways were opening up in an age of smartphones and Facebook and messaging with time and location information embedded. Ryan drew up a constitution and set up the Carly Ryan Foundation with the purpose of making it harder for groomers to succeed. Online security was a new field and in 2010 she attended the first cyber-safety conference, in Canberra.

None of this was easy. Her first initiative was to educate teenagers about the dangers of being online, which meant going into classrooms and school halls to talk to the kids about what happened to Carly, and how it happened. She was not there to tell them not to use social media but to show them how to use it safely. And because she was Carly’s mum, the kids would relate.

Working with Ryan, at the Foundation and accompanying her on some talks, is one of Carly’s friends, Katie Went. She says Carly was full of life and energy and it lifted you up to be with her.

“She was never in a bad mood, she was always happy,” Katie says. “She brightened up everyone’s day.”

Carly and Katie met the same way as Carly met the fake Brandon, on MySpace, and then they met in person and formed a friendship. Carly had even talked to Katie about the boy she had met online.

“They all thought he was a real boy,” Ryan says. “Being able to share that with kids today makes it very real for them.”

Ryan was not a practised public speaker and felt she had none of the skills she needed but she did it anyway.

“I just had to suck it up, and focus less on the self and more on what you can do to help others,” she says. “There were times before speaking I’d be vomiting, shaking, sitting on the loo but if I stand there and say ‘I can’t do this’, who is going to miss out on hearing the message?”

The first three years were gruelling, like Groundhog Day from Hell as she constantly revisited what happened to Carly and talked about suffering and what she had lost. But the Foundation was starting to make a difference and develop more focus as she teamed up with South Australian Senator Nick Xenophon to work through what became Carly’s Law. Her aim was to fill the perilous gap in the criminal code that prevented police from intervening when a child was being groomed.

“Often (police) will be watching perpetrators online that they know are preparing to harm, they might have fake profiles, they might be preparing to abduct, and they can’t do anything until they act,” Ryan says. The law, which passed in May, gives police the powers to intervene sooner, get DNA, seize technology and potentially, hopefully, stop nascent crimes from happening. Carly wouldn’t want a better legacy, Ryan says.

She had Nick Xenophon and others championing the cause and drafting the legislation — she would pretty much have Nick as part of her family if she could, she says — but the process was still tiring and complicated.

Amendments were rejected and had to be worked through and many MPs had to be convinced the danger was real. At a Senate inquiry, one of the arguments against the legislation was “well what if someone was playing Harry Potter and were embarrassed about being 40 and wanted to say they were 11?”. It might sound innocuous but Ryan is adamant that misrepresenting yourself as a child, particularly in an environment where children aggregate, can never be a good thing. “I cannot see any legitimate reason why someone would lie about their age to a minor online to play games with them, or do anything,” she says.

The problem for most people but children in particular is the difficulty they have in comprehending that there are evil people out there who want to harm or kill; paedophiles like balding, overweight Garry Newman who planned murder while using a fake identity to lure her to a date. Carly was a trusting girl who was much loved, and had people around her who appreciated the sunshine she brought into their lives. She was a girl who never seemed to be in a bad mood, was interested in others and was by nature sweet and kind. She was utterly defenceless against a predator online, and later in the flesh.

Ryan says people need to know the danger was real. “Of course what happened to Carly is the worst-case scenario, but if someone is abused as a child, if they don’t suicide they will struggle until the day they die over that agony,” she says. “A lot of people are suffering.”

Now, Carly’s Law is fact. It is illegal for adults to misrepresent their age to children online and police can better identify and shut down predatory behaviour. Ryan had a cup of tea with Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, just before his government announced the legislation and a memorial quilt made by the SA Quilters’ Guild from Carly’s favourite clothes hangs in Parliament House.

“I knew I couldn’t throw her clothes out but what could I do that she would think was pretty cool?” Ryan says. “She wouldn’t want me holding onto them and making them some kind of museum piece.”

A decade after Carly’s death and seven years since the Foundation began, Ryan has achieved every goal she set but she hasn’t finished. The schools-based education will continue — she is booked up until the end of the year — and she is focusing on a new target, which is the inadequacy of sentencing for serious child sex offences. She and Nick Xenophon’s NXT are targeting federal law that has a maximum penalty of 25 years but the penalty is rarely enforced. “The average sentence for serious sex offences against a child is 12 months, or a suspended sentence,” she says. “An abalone fisherman who takes too many abalone from the ocean will get a bigger sentence than someone who rapes a baby, so what is going on?”

The focus here will be on the courts which Ryan says should not be immune from criticism, and on judges who she wants to make accountable for sentences she says fail to recognise the damage done.

“I want to create a new sentencing regimen that will start nationally and filter down,” she says. “When you’re fighting for something that is right, how can people question that? It’s an obvious gross inadequacy.”

She is incredibly proud and sees herself as living testament to the fact that love endures all. She was an ordinary person catapulted into horror and she slowly transformed into something new, guided by the girl she lost.

“It’s really a story about the love between myself and my child, and look what it’s done!” she says. “I hope that it gives other people hope, in grief and death, that you can continue to breathe in and out and find meaning by thinking about what your loved one would want you to do.”

Visit the Carly Ryan Foundation at carlyryanfoundation.com

WHERE TO GO FOR HELP

Beyond Blue — 1300 224 636

Adelaide Counselling Practice — 0407 405 733

Lifeline — 13 11 14

Men’s Line — 1300 789 978

Kids’ Helpline (for those aged 5-25) — 1800 551 800