Camp, glamp with threatened rhinos in Adelaide safari park

Monarto is putting the finishing touches on a glam camping experience, which will help bankroll a plan to create the largest sanctuary for the threatened rhino outside Africa.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Monarto Safari Park is putting the finishing touches on an Australia-first camping, glamping and high-end safari tourism experience – the likes of which you would only find on the African plains – to bankroll a plan to create the largest sanctuary for the rhino outside Africa.

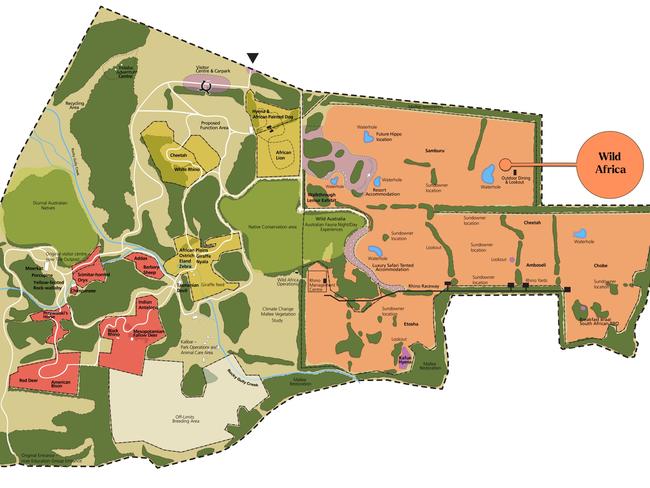

By the middle of next year, Monarto will open its centrepiece Wild Africa development.

This will house a range of free-ranging species – including the Oryx and rhino. It’s been planted with specific grasses to both feed the animals, and to create scenes reminiscent of the African Plains.

At first glance, the similarities are stunning, helped in no small part by the waterholes being dug throughout the park.

Wild Africa will also include a $40m, 78-room luxury hotel and glamping experience being built by Jayco founder Gerry Ryan, which will allow people to mix with the wildlife, emulating the high-end safari experiences in the likes of Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Beyond that, the overarching plan is to bring as many as 30 rhinos, mainly southern white rhinos, from South Africa to Monarto within the next few years to live and breed.

This is the story of the people behind the plan ... and why they care so much.

Peter Clark can’t recall a precise moment, anecdote or incident that lit the fuse for his decades’ long mission to help save the rhinoceros.

“But this probably sums it up as well as anything,” he says, as he clicks on an image on his computer.

A moment or two later it appears. A mature rhino with a deep, long gash where its horns used to be, stares directly at the camera.

It is an image taken by Clark during one of his many visits to southern Africa.

It is at once confronting and heartbreaking.

“He breathes through the top of his head now,” says Clark, the director of Monarto Safari Park and one of SA’s most acclaimed conservationists.

“But he’s one of the lucky ones. Normally the poachers just shoot them and hack off their horns with axes.”

So he’s alive then?

“Yeah, he’s still going. There’s plenty that aren’t.

“I loved this guy. I was keen to get him over here, because he really tells the story, but we couldn’t.

“So there’s a lot of reasons but mainly it’s just to do with how vulnerable rhinos are and how vicious, cruel and uncaring the poachers can be.”

As we meet in his office at the front of a recently revamped Monarto visitor’s centre, it matters little if and when this fire was stoked.

The fact remains that, today, Clark and his tight-knit Monarto team are at the forefront of a world-first plan to, among other things, create what will likely be the largest sanctuary for the rhino outside Africa.

LOST IN SPACE

South Australia has a lot of things going for it but, when it comes to the rhino, the No.1 asset is space. Lots and lots and lots of space.

And in this respect, Monarto is the poster child.

Its climate and flat landscape is similar to southern Africa – aside from being a little hotter in summer, perhaps – and its ample space, at last count upwards of 1500ha, already allows 60 species of animals to roam free, which includes a herd of more than 50 scimitar-horned oryx, which are extinct in the wild.

Not to mention itsgroup of five rhinos, known as a “crash”.

By the middle of next year, the plan is to finally open its centrepiece Wild Africa development, the timing of which has been pushed slightly back due to delays caused, at least in part, by the pandemic.

This will house a range of free-ranging species – including the Oryx and rhino. It’s been planted with specific grasses to both feed the animals, and to create scenes reminiscent of the African Plains.

At first glance, the similarities are stunning, helped in no small part by the waterholes being dug throughout the park.

Wild Africa will also include a $40m, 78-room luxury hotel and glamping experience being built by Jayco founder Gerry Ryan, which will allow people to mix with the wildlife, emulating the high-end safari experiences in the likes of Kruger National Park in South Africa.

Beyond that, the overarching plan is to bring as many as 30 rhinos, mainly southern white rhinos, from South Africa to Monarto within the next few years to live and breed.

The ultimate goal is to build an “insurance population” for the species which, if necessary, can eventually lead to the repatriation of African rhinos back to their homeland.

The best case scenario is this will support the species if it continues to be endangered.

At worst, it is a standalone back-up population if the rhino becomes extinct in Africa.

However, it will take time.

Done in partnership with The Australian Rhino Project, Taronga Conservation Society and Orana Wildlife Trust, it has faced more than one biosecurity hurdle, the most recent being the pandemic. The fix is to first move the rhinos from Africa to Orana Wildlife Park in Christchurch, New Zealand.

There they’ll stay for about 12 months, with the first trip expected to kick off later this year.

Once here, likely towards the end of 2023, they will face a few more weeks quarantine in a newly built hub at Monarto, and then be released into the park via a 2.5km raceway, which is also under construction.

“Without that, we’d need to crate and crane them every time we try and move them around the park,” Clark laughs.

They’ll arrive in small groups over a period of time; at around 2000kg each, this is a practical consideration as much as anything else.

“So currently, it’s about 55 rhinos in zoos around Australia and New Zealand,” Clark explains.

“And we’re thinking that we’d like to get that up over 100.

“And those sorts of numbers should be able to probably keep rhinos going here for about 70 or 80 years, without any major input or importations, except between sites in Australia.”

Clark is frank when he says the dollars Wild Africa will generate – and it should be plenty given the experience on offer coupled with, finally, the rear-view mirror aspect of Covid – will help fund the conservation work for Monarto and Zoos SA, which remains a not-for-profit entity.

“We want to knock two bottles off the wall at one time, and that is basically build up a reasonable size insurance population, and also develop a new safari accommodation experience, which funds it,” he says.

Clark says from here they have no choice but to act; the alternative is unthinkable. In many ways for him it would be the culmination of a life’s work; in July last year he received a UNESCO Achievement Award for a conservation career spanning 45 years.

“What we are doing is supporting conservation in Africa and setting up an insurance population, which is just logical to do now,” he says.

“Since we thought about this, they’ve already lost the western black rhino, it’s completely extinct. The northern white rhino’s just down to two females.

“And then there’s one of the Sumatran rhinos subspecies, which is dead, gone.

“So there’s been three subspecies of rhino lost in the last 15 to 20 years.

“And southern white, which went from maybe less than 100, 100 years ago, then back up to nearly 20,000, because of a lot of good work that was done over there and in zoos, but is probably now back somewhere between 5-10,000 and going back down every year.

“And it’s gonna get worse.

“The poaching numbers have decreased somewhat. But so has the number of rhinos. White rhinos aren’t as easy to find for poachers as they used to be.

“So I would hate to think that we sat on our backside while we had this opportunity.”

THE CRISIS

In 2017, poachers broke into a French zoo, shot and killed the resident four-year-old rhino, Vince, and chain-sawed off his horn.

The callousness of the act brought world attention to the illegal horn trade, which has been the scourge of Africa for decades and has led to the species being under siege.

About 500 rhinos were killed in South Africa last year and around 10,000 in the past decade. It is estimated that, at one stage, poachers were killing one every six hours.

Experts are concerned that, at this rate, the species could be extinct within 10 years.

The lure is, of course, the horn, which is wrongly assumed to have medicinal properties.

Regardless, it is worth more than gold and cocaine on the illegal black market, an estimated $100,000 a kilogram, which poses a never-ending problem for rhino conservation reserves and, as 2017 showed, even overseas zoos.

Today, three species of rhino – black, Javan, and Sumatran – are critically endangered. The southern white rhino is classified as near threatened.

Clark says the attraction of the horn these days is less about the debunked medicinal benefits and more simply the status.

“They make drinks out of it, they use it for prestige stuff,” he says, rolling his eyes.

“And, you know, you might as well make a drink from your fingernails, it’s just keratin, the same stuff.

“It’s gone past the ‘it can cure anything from impotence to cancer’, to the stage where it’s very prestigious now in some countries to have on your lounge room table.

“And you can shave off bits to use in a drink for your guests and all that sort of stuff.”

Beyond the obvious conservation concerns, the only other real worry for Monarto is security.

If poachers can get into a French zoo, can they get into a relatively remote South Australia wildlife park?

This is the only time Clark is slightly cagey.

“We are one of those places that tries to think of this ahead of time,” he says simply.

“So even though there’s been no incidents, we’re just adding to our security all the time.

“There’s a lot of technology out there now.”

End of subject.

The Rhino Whisperers

Google “rhino whisperer serenades rhino calf” and you’ll find a video of Mark Mills seated in a small brick hut, playing gentle acoustic guitar to a calf, who appears to be recovering from injuries, its ears covered with white bandages.

It begins quietly sniffing the guitar, takes in the soft music then, after a while, turns and sits at his feet. A moment later it nestles into his leg and appears to drift off to sleep.

Mills is modest about his guitar playing and a little uncomfortable with the term “rhino whisperer” but is proud that this little video went viral around the word and literally struck a chord with tens of thousands of people.

“It just made the whole rhino poaching plight a little more visible to people,” he says.

“For me, that video reminded us that even the largest, most dominant rhino bulls, all begin their lives as little tiny calves like the one in the video. Totally vulnerable to the terrible things that the rhino horn trade does to them.”

The video was filmed during a working visit to a sanctuary near Kruger National Park in Mpumalanga, South Africa, for Monarto’s senior ungulate keeper in 2017.

“I had this real desire to work with rhinos in Africa, to do whatever I could in assisting in the response to the poaching crisis,” Mills says.

He worked for Care For Wild Africa, an organisation that rescues and rehabilitates rhino calves whose mothers have been killed for their horns, nursing them back to health, and integrating them into other groups of rhinos.

“I think we took in about six calves during my time there, often with horrible injuries,” he says.

“Once the poachers have killed the mother rhino and taken her horns, they tend to use the calf for target practice, or simply hack at it with their machetes.

“They simply don’t care.

“I did see some awful things during my time there, but also some of the wonderful things being done by very dedicated people to help save rhinos.

“It was incredible to be involved and understand what it’s like to manage and care for rhinos in the middle of the most terrible poaching crisis that the world has ever seen.”

He returned emboldened with his desire to continue the work at Monarto and play his own role in fighting for the future of the species.

“I wanted to expand on our role here and looking to the future, we’ve got loads of space here, a great rhino habitat and we’re looking to have the rhino population on site increase over the years, so there’s somewhere that’s safer in the world from poachers than back in Africa,” he says.

Mills has been at Monarto since 1999, but his passion for wildlife runs deep.

As a child he was taken by the adventure series of novels by US author Willard Price which told the story of brothers Hal and Roger Hunt, who capture animals for their father’s collection on Long Island, New York.

“The boys travelled the world, capturing and collecting animals for zoos,” he says.

“The books were written back in the 1950s or thereabouts and so the language is a bit crude, but I remember reading them as a 10-year-old boy and being obsessed by the stories.

“They honestly planted a bit of a seed in me all those years ago and began my fascination.”

From there spawned a genuine affection for wildlife generally, and rhinos in particular.

“People tend to think about the rhino as lumbering, grumpy creatures,” he says.

But really, they are extremely co-ordinated and agile on their feet.

“They’re very gentle as well, and wonderful to work with.

“They respond very well to positive reinforcement, and people are surprised how we are able to handle them.

“They also love a really good scratch.”

It’s a passion shared by fellow keeper Riley who, on the day we visit, is busy ensuring Ibutho, the first rhino bull housed in Wild Africa, is getting his daily fix of feed and exercise.

“He pretty much eats all day, I mean look at the size of him,” he says, as Ibutho munches constantly on his feed mix. He consumes up to 50kg of food each day.

The connection between Riley and Ibutho is not forced.

When he calls him, raising his voice an octave, “come here boo”, the rhino responds in an instant, walking smoothly to follow the voice (they have poor eyesight, great hearing), his slow, deliberate movements belying the fact he can reach up to 40km/h on the plains.

Riley (full name Paul Riley but no one has called him Paul since kindergarten) has worked with the likes of grizzly bears in Canada, but reckons he has found his calling with the rhino.

“I don’t mean it to sound corny, but I just love them. In one sense they’re just majestic, but they also respond really well to us and the way we treat them,” he says.

“On the one hand they’re really tactile, so they love to be touched. If you treat them well, they will learn to trust you and respond to you.

“And they need us.”

Now, alongside the obvious conservation aspects, Riley and Mills simply want to spread the word.

“One of the things I really enjoy doing is conducting behind-the-scenes tours where people can come and meet the rhinos,” Mills says.

“People are surprised that they can come into the park here and get so close to them, and touch and feel them. Rhino are extremely tactile creatures, and people can make real connections with the rhino during these tours. It’s such a special experience that we can share with people, right here in South Australia.

“That’s one of the things that gets me excited – sharing what we do and having people come across and connect with the rhinos we have.

“They’re truly amazing animals and we’re lucky to have them.”