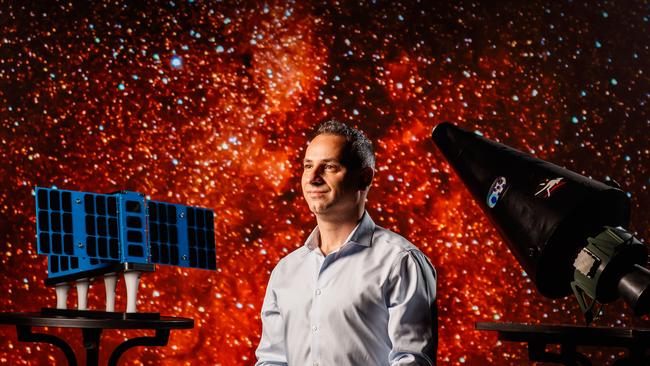

The remarkable story of the man leading our mission to the stars

As a kid, Enrico Palermo wanted to be an astronaut, but now he’s head of the Australian Space Agency and believes humans will be launched into space from Australia within a decade.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Enrico Palermo always wanted to rocket into space.

“I wanted to be an astronaut, that was the goal,” he says.

Palermo hasn’t quite made it to the stars – but that’s not to say he’s not a spaceman.

His out-of-this-world dreams now are in his capacity as the chief executive of the fledgling Adelaide-based Australian Space Agency, building space up to be a $12bn industry by 2030.

A long way from home

But space is a difficult place to reach for a young boy from Western Australia, born into a large Italian immigrant family. Palermo loved maths and science and studied mechanical engineering and physics at the University of WA and then took a job with oil giant Woodside as an engineer supporting offshore platforms.

It was a career he could have easily settled into for a long time. But.

“I learnt a lot there that I think I still utilise in things I do today. But it’s like, this isn’t … what I wanted to do. It wasn’t a passion,’’ he says.

He had just become engaged to his now-wife Nadia, and he started applying for jobs in Europe.

“Nadia’s like, ‘are we coming or going? We want to get on with our lives. You’re looking at jobs in Europe. What are we doing?’”

On New Year’s Eve 2004, a decision was made. It was time to take a risk. Palermo quit Woodside and Nadia, an accountant who was working in the resources sector, left her job as well. Their next stop was London.

“Overnight, it was a different environment… you start to see this belief you could do anything,” he says.

Palermo worked as a business analyst for a UK start-up that specialised in composite materials. There was opportunity for him to set up offices for the company in the Asia Pacific, but that was not why he and Nadia had left WA.

So, he took another risk and left that job as well and then won a scholarship to the International Space University in Strasbourg, France. For nine weeks in the summer of 2006, Palermo studied space policy, space law, space engineering, space design and operations.

There, Palermo met Alex Tai, who was then chief operating officer for Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, who had given a presentation on the company’s grand plan for space travel. It was early days for Galactic but Palermo says they were “looking for someone that had sort of a combination of engineering but also business”.

He signed up and became one of Galactic’s earliest employees. There were fewer than 10 when he started work in the company’s London office. For the next two years he shuffled between London and Los Angeles, from where he would take the 150km trip north to Mojave, a small town which has been at the heart of the US aerospace development since the 1940s.

In Mojave, there was a company working on the prototypes for the spaceship program and Palermo helped develop a business plan.

By the time the spaceship was approaching test flights, Palermo and Nadia had moved to Mojave.

“We moved from central London, that cosmopolitan mixing pot, amazing city to Mojave. It’s a small town. Four thousand people in the desert.”

But if you are in the world of aerospace development Mojave is where you want to be.

Edwards Air Force base is 10 minutes down the road. That is where Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in 1947. This is where the space shuttle used to land and it is home to the US Air Force’s test pilot school and NASA’s flight research centre.

“There was an environment there to have a community that would support you firing rocket motors and flying spaceships,” Palermo says.

This was the Palermos’ home for the next 12 years and where the couple’s sons were raised.

The US base

The children grew up watching spaceships being built and being taken before dawn to watch test flight preparations.

Palermo, 42, became president of the Spaceship Company and was promoted to Galactic’s chief operating officer before the lure of a move home.

“The opportunity to lead a nation’s space agency is very rare,” he says.

Flying home

The family arrived home in Australia in November 2020 and he says they have settled in well to Adelaide life. Nicola is now eight and Alessandro seven, and their father says they are happy being in school after Covid-enforced shut-outs in the US.

Palermo liked working with Virgin’s ebullient founder, billionaire Richard Branson.

Branson, with fellow billionaires Tesla founder Elon Musk and Amazon’s Jeff Bezos have led a new generation of commercial space exploration. Branson and Bezos made it to space last year on their company’s rockets, drawing criticism from some that it was a billionaire’s frolic.

Which is not how Palermo sees it.

“Anything humans have done in space has had profound effects back here on earth,” he says. “Space is the reason we know the condition of our planet and are able to monitor it, so the more we can access space, (make it) lower cost, more reliable, we’re going to enhance our understanding of climate change and how we adapt to it,” is one example he gives.

Palermo believes eventually space travel will be in the reach of most. In its third quarter financial results released in November, Galactic said its “private astronaut commercial service” was on track to start late in 2022. It said it was selling seats on flights for $US450,000 ($630,000). Despite the extreme cost, Virgin Galactic said it had sold 700 out of 1000 tickets.

Palermo compares it to the early days of commercial aircraft flight a century ago, when taking a ride in an aircraft would have been regarded as out of reach for the average person.

“Through innovating, through learning, through failure, through setbacks … we have airliners now that are safer than driving a car around the city. I see the same thing happening with space,” he says.

Palermo sees a grand future for Australia in a global space industry that is predicted to be worth between $1 trillion and $3 trillion by 2030.

Next year, NASA will launch a rocket from a site near the Northern Territory town of Nhulunbuy, the first of what is expected to be three launches.

Palermo is also passionate about Australian companies being heavily involved in the broader industry. He talks of Australian companies supplying components, launching satellites, operating spaceports, communications or even space medicine.

This is where the predicted $12bn revenue and an additional 20,000 jobs will be created.

“It’s an ambitious goal,” he concedes, before predicting Australia could top it.

Australia, he says, has some strong advantages compared with other nations vying for the space dollar.

One is Australia’s heritage in space. Australia became one of the first countries into space when the Wresat satellite was launched in 1967 and played a crucial communications role in NASA’s space program. Our geography is another advantage.

“Australia’s location on the planet, its view of the sky, and its stable, geopolitical climate is good for understanding the space environment,” he says.

And there’s “our view of the eastern and southern hemisphere, which other nations don’t have.”

In 2019, the Australian government announced a $150m program to help Australian businesses build capabilities to join NASA’s Artemis lunar program and its Moon to Mars ambition.

At the same time, ASA and NASA signed a letter of intent confirming potential Australian involvement in “areas of mutual interest such as robotics, automation, and remote asset management – similar to that currently used by Australia in mining operations”.

Palermo says some of the technology used in the Australian mining industry to guide machinery that is thousands of kilometres away could be adapted for use on the moon.

It’s the same for medicine. The Tasmanian-based Centre for Antarctic, Remote and Maritime Medicine provides medical support for the Australian Antarctic Program, as well as others who are operating in the Southern Ocean.

The federal government handed out grants of up to $200,000 to 20 companies earlier this year to help companies through the “technology readiness and development curve”.

“If we can start to get that hardware into space in the harsh environment of vacuum radiation, temperature extremes, suddenly you have a product you can sell,” he says.

Then there is the Moon to Mars Trailblazer program. The federal government is putting up $50m to help an Australian company design a small rover that will head to the moon with NASA, possibly in 2026.

Australian companies are already making headway in space. Outfits such as Flavia Tata Nardelli’s Fleet Space Technologies has already launched six nano satellites.

And alongside Palermo’s Australia Space Agency at Lot 14 on North Terrace are other companies such as local start-ups Inovor Technologies, Myriota and Neumann Space.

“This is so exciting,” he says with the air of a man who loves his job.

But will we find anything out there? From a purely mathematical point of view he thinks it’s likely.

“I hope we’re not alone but space is big and you know, how many millennia away are some of these things. So, yeah, I don’t know what the right answer is,” Palermo says. ■