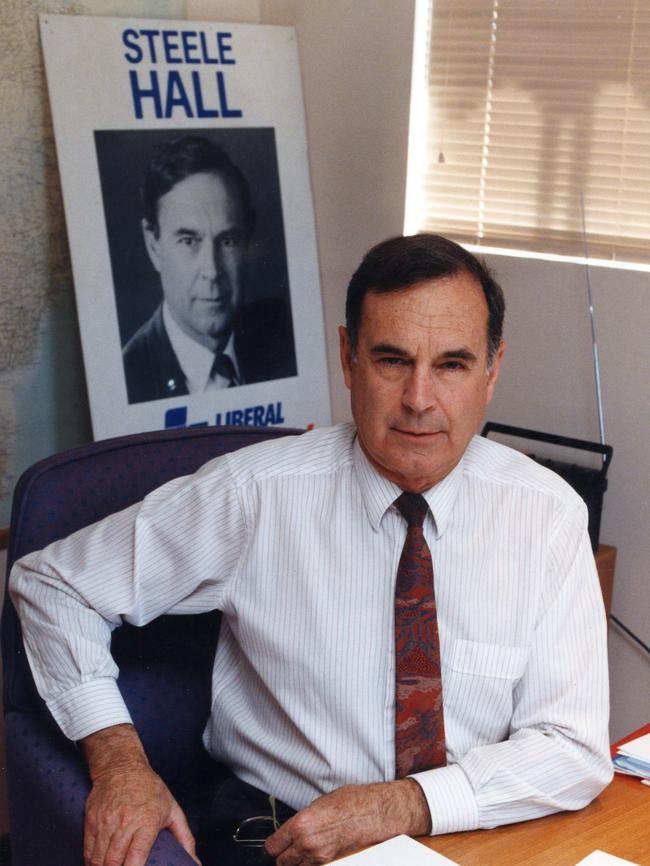

Steele Hall’s lessons for the Liberals

STEELE Hall’s Liberals won government 50 years ago thanks to an independent. The similarities between the 1968 poll and next month’s likely cliffhanger are uncanny.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE Queen was highly amused. It was June 1968 and a dashing young South Australian Premier, Raymond Steele Hall, turned up at Buckingham Palace to present his credentials, suffering from a serious hangover.

The previous night, Hall had been to a business dinner in London’s snooty East India Club and was then introduced to the city’s nightlife and Scottish whisky by a fellow guest, a member of the Grenadier Guards.

They ended up at comedian Danny La Rue’s nightclub and Hall got to bed close to 4am.

When he woke he was in a parlous state. He couldn’t open one eye and could barely speak.

His travelling companion, the head of the Premier’s Department, John White, pushed him through a cold shower, ordered a car and they drove to Buckingham Palace.

“I sat in an anteroom and when I met the Queen I had to confess I was suffering from British hospitality,” Hall recalls. “She summoned a butler and ordered black coffee.

“She thought it was hilarious. She was well briefed on South Australia and we laughed our way through a lovely meeting.”

That was 50 years ago, 14 years after Queen Elizabeth’s coronation and three months after Hall was elected as the Liberal Premier, defeating the Labor Government led by Don Dunstan in what has become known as the battle of the matinee idols.

Hall was 39 and the Queen was 41.

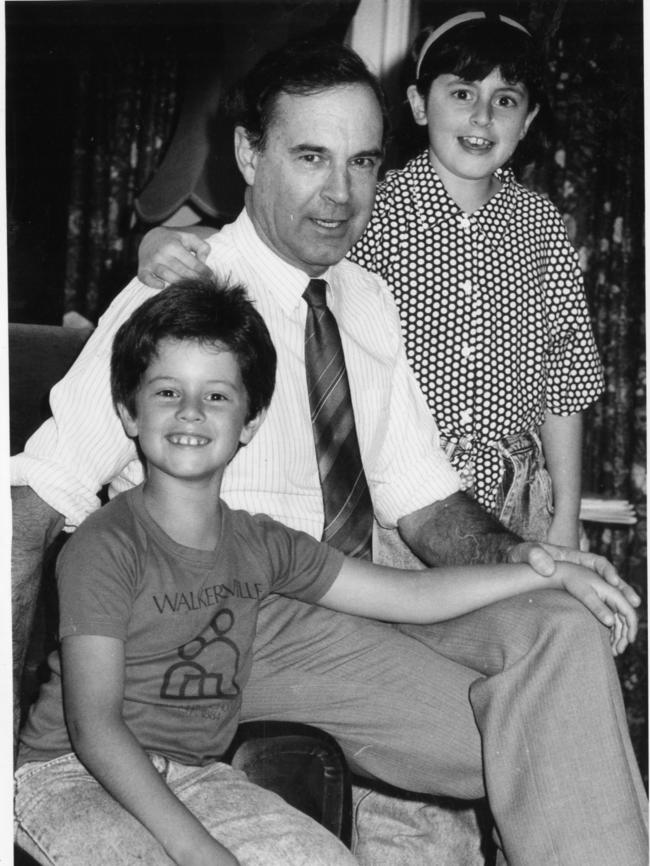

Hall is 89 now, thin as a whippet and with a slight stoop but still active and inquisitive. He reads newspapers, watches Federal Parliament on television, tinkers in his shed, does odd jobs around the house, devotes time to his adult children and occasionally dabbles in the garden.

He has just helped build a butterfly room – a bird-free enclosure – for his wife Joan in the backyard. The butterfly room allows caterpillars to develop free of the danger of being snaffled by birds. When the butterflies emerge, they fly free.

Hall is working on a book about his years in politics, first in the State House of Assembly, then the Senate and finally as Liberal member for Boothby for 15 years in the House of Representatives.

He is the only state premier and one of the few politicians to sit in three houses and the oldest living Australian state premier.

Hall remains passionately interested in politics although he has all but abandoned public life. He is a life member of the Liberal Party State Council and, as a curiosity, he remains a member of the Young Liberals and often provides advice to prospective Liberal Parliamentary candidates. He plans to hand out how-to-vote cards in the coming state election.

“I don’t have any serious involvement with the party or politics these days,” he says, quickly adding, “but whatever you write, don’t forget that I am a Liberal.”

He is confident the Liberals can win this year’s state election under Steven Marshall – 50 years after his own victory – and return to government for the first time since 2002.

“The Labor government has run out of ideas,” he said. “It’s been there too long. The Liberals would have a fresh approach, which would help invigorate the state. But just as an independent influenced the decision in 1968, the effect of Nick Xenophon will have an influence this year.”

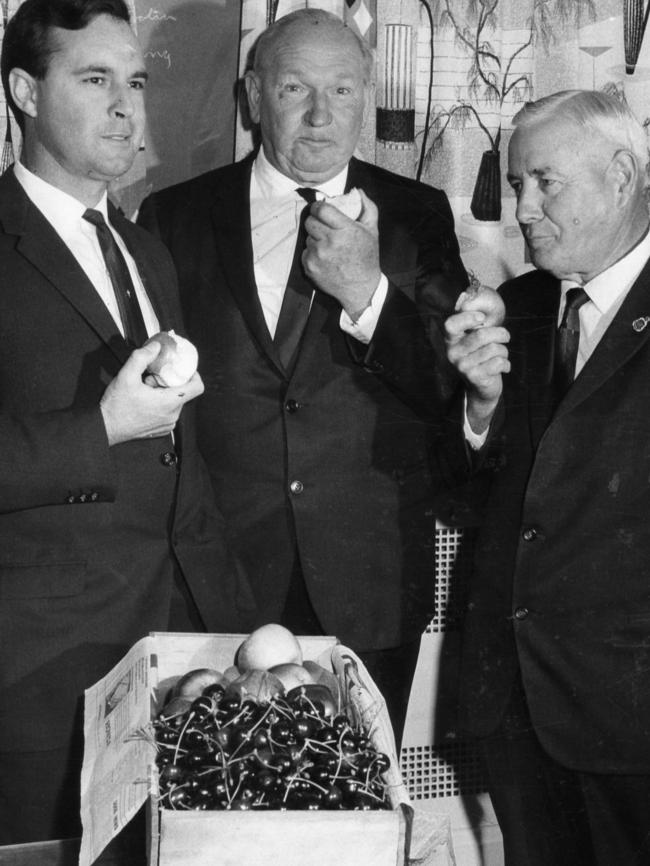

When Hall – a farmer from Owen – entered politics in 1959, Sir Thomas Playford was Premier. “He was very nice, very powerful. He was a great mentor.”

Playford was Liberal Premier for 27 years until he was defeated by Frank Walsh’s Labor Party in 1965.

Hall has many stories of Playford. A sample. Once, during a country tour, Hall set up some twigs in the ground and challenged Playford to a shooting contest. Playford’s first shot neatly clipped the wood but Hall missed.

Playford refused to try again: “Not on your life. I don’t have to prove myself twice.”

When Playford had the upper hand, he kept it.

Hall and Playford often played snooker in Parliament House and endlessly discussed politics. The master and the apprentice.

When Playford retired in 1966, Hall – with Playford’s blessing – replaced him as Liberal Leader. At the time, the two men finished a game of snooker and Playford handed Hall his cue saying: “Here, take this. I’ll never use it again.” It was a symbolic passing of the baton.

“This little interchange led me to reflect on the drama of political life, how change can be sudden and unexpected, how deeply competitive even friends can be and how, in the end, if you last long enough, age will shunt you out.”

Hall still has the cue.

After the knife-edge 1968 state election, it was clear the Liberals could only govern with the help of an independent, Tom Stott.

Hall: “I decided the position was intolerable. I could not lead a government that depended on the egotistical Tom Stott. We would have to have another election.”

An hour later Playford rang Hall and said he had spoken to Stott who would support the Liberals if he was made Speaker.

Hall recalls: “When I told Tom (Playford) I wouldn’t govern in this circumstance he shifted into his rather terse and abrupt mode. Twenty minutes later, obviously well-schooled by Playford, Prime Minister John Gorton rang.

“His indignation at my refusal to go along with Stott was something to endure. He hit home when he said: ‘What right do you think you have to deny government to the thousands of people in the Party who worked their butts off to make you Premier?’”

Hall agreed to form a government dependent on the casting vote of Stott, an unpredictable and irascible political veteran.

Hall’s first decision as Premier was to sign “one of the most wretched letters I’ve ever had to devise”.

Scientist Sir Mark Oliphant had accepted an invitation from the outgoing Premier, Don Dunstan, to become the next governor. “We of the new regime didn’t want him,” Hall says.

He effectively withdrew the offer. Hall says: “Oliphant’s reply conveyed far more than the brief eight words in which he packaged it.” It read simply: “I acknowledge your letter of the 10th instant.”

Oddly Oliphant and Hall later became good friends and Oliphant was eventually appointed governor by a Labor government.

Hall’s amusing meeting with the Queen at Buckingham Palace was not his only brush with royalty.

When the Duke of Edinburgh visited Adelaide, Hall introduced him to fiery Labor frontbencher Sam Lawn. Grabbing his opportunity, Lawn told the Duke that because of unfair electoral boundaries, South Australians lived in a dictatorship. He suggested the Duke read a book which he was about to name when the Duke cut him short.

Hall recalls: “The Duke then let loose a very succinct message at 100 decibels in a voice that would have passed for a controlled scream: ‘Read the bloody book yourself.’ Lawn was left speechless.”

As was common in the ’60s, Hall had never been overseas. Before his London visit he went to Japan, which was a country of some mystery. He was guest at a formal Japanese dinner and had to follow the Japanese custom of removing his shoes at the door.

“To my horror, as I removed my right shoe, I stared at my big toe, showing out through the only holey sock in my wardrobe,” he recalls.

“I was led then by a beaming geisha across a wooden floor that exposed my wandering toe to the top Japanese executives from our afternoon conference.” Courtesy prevented anyone from mentioning the holey sock.

In spite of his one vote majority, Hall was determined to govern as if his administration was in a position of strength. He knew the Liberals would struggle to win the election due in 1971.

It was a hectic two years. Hall modestly declines to list his achievements in government but his unpublished manuscript lists many.

They include: endorsed and started the MATS plan (Metropolitan Adelaide Transport Study) for a 20-year construction program of Adelaide metropolitan transport, remedied faults in plans to establish West Lakes, purchased broad acres for future housing, fluoridated Adelaide’s water supply, established intermediate courts, introduced abortion law reform, built the Outer Harbor terminal, approved and selected the site of the Festival Centre, banned Scientology, negotiated a 20 per cent increase in River Murray water, refused to appoint a communist (Elliott Johnston) as a QC, established the SA Environment Authority and brought natural gas to SA.

One of Hall’s first decisions as Premier was to proceed with the MATS plan, which was the result of a study established by Playford. It involved the establishment of a system of freeways through the Adelaide metropolitan area. It was eventually scrapped by the incoming Dunstan Government in 1970. Land purchased by the Hall government for freeways and corridors was sold.

“It was a tragedy that MATS was defeated,” Hall says, in a rare moment of frustration. “If MATS, in principle if not in detail, had been started there would be no traffic congestion or chaos like there is in Adelaide today. It was a missed opportunity to implement a total transport system. It was started. We bought 1200 houses. It was ready to go.

“But Labor missed the opportunity. This was a huge disappointment to me. We are now patching up the system but we will never catch up. There is no plan, no vision.”

If the loss of MATS was a frustration, Hall sees the redistribution of electoral boundaries as one of his great achievements.

“There were some strong Labor seats with 40,000 voters and some Liberal seats with 5000 voters,” Halls recounts. “It was totally undemocratic, totally wrong. We could not continue with the boundaries the way they were. The changes we made in the electoral boundaries were immense and we knew that we were sacrificing government at the following election, but it had to be done.”

Few people remember that it was Hall who selected the site of the Adelaide Festival Centre. While he was in London he walked along the Thames Embankment and saw the Royal Festival Theatre overlooking the river.

“When I came back Cabinet and the Adelaide City Council had approved a site in North Adelaide – the old Carclew property – for the theatre. I walked from the weir to the zoo and decided the theatre should be on the site of the old City Baths, where it stands today. We overturned the decision of the Cabinet and the Council.”

He signed off on the plans for the theatre complex but admits, without rancour, that he received no credit for his decisions. “I got to go down to the site for a photo opportunity with a bulldozer when construction commenced. We were out of office when Gough Whitlam opened it in 1973,” he says.

“When he was Premier, Mike Rann offered to name a new footbridge from the Festival Theatre to the casino after me. I declined.”

Dunstan is widely regarded as the first Premier to raise concerns about the environment. But it was Hall who started it.

“In 1969, my political antenna sensed an increasing concern about the environment,” he says. And so the Committee on Environment was created under the chairmanship of Professor Denis Jordan. Ironically, it was Dunstan who received some of its earliest recommendations.

Hall has no titles or letters before or after his name. “Not interested,” he says dismissively.

He declined to accept the title “The Honorable”, which is the right of the Premier, and for many years the list of Premiers, set in bronze near the entrance to the House Assembly, listed Hall as the only “Mr” among the Honourables. But recently, without Hall’s agreement, the “Mr” was quietly chipped and replaced by “Hon.”

Hall was in government before Premiers and Ministers employed an army of press secretaries and personal staff. But he agreed to the Government buying a $10,000 camera to pre-record announcements. He refused to extend the budget to buy an autocue to read his script. Instead he came to work with a length of fencing wire, bent it into a frame and one staff member fed the script in at the top and another pulled it through from the bottom. The ingenuity of a farmer.

Hall’s determination to support the construction of a dam at Dartmouth in Victoria to supplement Adelaide’s River Murray water supply precipitated his defeat in 1970. Labor wanted the dam at Chowilla on the River Murray, a decision supported by Speaker Tom Stott, who was a Riverland member.

Stott voted with Labor against Dartmouth, an election was called on the new electoral boundaries and Labor under Dunstan was swept to power.

Hall declined to criticise Dunstan, although they were never close. “I never had rows with him. I had no personal dislike because I didn’t have contact with him.”

Did he regret the dam decision? “No. Chowilla was wrong and unsustainable. In the end, after the election, Labor supported Dartmouth, which was the right decision. They had no choice.”

Hall’s bitterness toward Stott for forcing the election is palpable. Years later, when Stott died, I rang Hall seeking a tribute. “Goodbye, bastard,” he said. “That’s all I’ve got to say and you can print it if you want to.” It was edited out of my copy.

And then a revelation, which could have changed the course of political history in SA – the 1970 election could have been avoided. Stott approached Hall and asked for a knighthood. He wanted to be Sir Tom. Hall refused. Instead he offered Stott a state funeral.

“Now, years after the event, I know I was wrong,” Hall says. “I should have swallowed my pride and knighted cranky old Tom Stott. If I had given him a knighthood Tom might have been indebted enough to vote for Dartmouth.”

That would have avoided the election and given the Hall administration another year in office. Who can predict what might have happened in that year?

Hall says it is 1077 steps from the Premier’s office in Victoria Square to the Leader’s office in Parliament House, but a continent away in resource and opportunity. But he was not idle.

In Opposition Hall wanted to reform the Liberal Party and was eventually dumped as Leader in a bitter battle of Party ideology and direction. It was a classic struggle between conservatives and progressives, not unlike the current dissension in the federal Coalition.

Were you betrayed? “No, I don’t think so. That’s politics.”

If you had remained leader could you have won the 1975 election? “There’s a chance I could have made it but there were too many difficulties in the Party.”

Hall established the Liberal Movement – a reform group within the Liberal Party. Initially the Liberal Movement had 11 Liberal members but when it split completely only four members left the Liberals. At the 1975 election the Liberal Movement won 20 per cent of the state vote and had five members elected. In 1976, the warring parties reunited although former Attorney-General Robin Millhouse remained separate and eventually joined Don Chipp’s Australia Party, which ultimately became the Australian Democrats.

Hall won a seat in the Senate as a Liberal Movement member in 1974 and for 18 months held the balance of power. He later returned to the Liberal Party and was Member for Boothby from 1981 to 1996.

“When I held the balance of power in the Senate Gough Whitlam was Prime Minister and he would ring me at 11am on Parliamentary sitting days and tell me what he was going to do that day and asked if I agreed with it,” Hall recalls.

“We negotiated amendments to legislation I didn’t like – I remember the nine-hour debate on the Trade Practices Act, which the Liberals opposed.

“It got through and when the Liberals came to power they strengthened the legislation rather than throwing it out.”

Can the Coalition win the next federal election: “Yes, I think they can. (The Opposition Leader, Bill) Shorten is a dangerous man without principles. He never takes anything vaguely like a responsible position on anything. Australia would not be a nice place to live if he became Prime Minister.

“I think the Prime Minister (Malcolm Turnbull) is showing signs of coming good. Yes, I think they can win next time.”

How much have politics changed since you were in Parliament? “Immensely. The introduction of social media and the 24-hour news cycle have changed everything. It is much harder now.”

Do you have any regrets after a 30-year career in politics? “No, not really. Frustrations perhaps about things like the MATS plan and the Dartmouth decision, but no regrets.”

If you were a young man would you enter politics today? “Probably not. But I had a pretty good ride.”