Adelaide’s statues: The good, the bad and the scandalous

An opium trader, the man who introduced the bill to give women the vote and a donkey. Read the stories behind SA’s statues.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s easy when walking through the city to ignore what’s above your head. There you are, too often looking at your shoes, avoiding other pedestrians or squinting at your phone. But what’s up there has increasingly become a point of conversation. All those bronzed likenesses from a century ago. All those yesterday’s heroes.

The value and meaning of statues and monuments came under increasing scrutiny last year as Black Lives Matter protests ignited around the world. The fate of the 17th century slave trader Edward Colston, cut down and dumped in a harbour in Bristol, England, drew global attention. In the US, memorials to confederate soldiers were removed. Vandals attacked memorials to Captain Cook in Sydney. In Adelaide, Colonel Light’s statue on Montefiore Hill was attacked, with No Pride in Genocide and Death to Australia graffiti.

It was decided last year that a new statue of Queen Elizabeth II by celebrated artist Robert Hannaford should be placed on the lawns of Government House, rather than on North Terrace to protect it from potential attacks from vandals or those seeking to make political statements about the colonisation of Australia.

Flinders University history professor Peter Monteath believes having the discussion about the value of statues is fine, but isn’t endorsing the iconoclastic view that statues should be torn down.

“If anything, the most productive thing that can happen is that you have discussions about what is worth preserving and what is worth knocking down,’’ Monteath says. “A discussion by its nature is dynamic and monuments aren’t. The discussion is the healthy thing because you are then engaging with the past rather than drawing a line under it.’’

The irony, Monteath says, is that we are now paying attention to statues we have long ignored.

To start, take a walk down North Terrace. You might notice the War Memorial, it’s hard to miss. And nobody is suggesting that should go. But what about the statue of the great navigator Matthew Flinders? Up there, looking a little quizzical, sword on his right leg, telescope in his right hand. It’s both imposing and easy to miss. It’s up there somewhere, almost lost in the North Terrace trees, looking across at the Myer carpark.

Possibly not the grandest view in Flinders’ long history of exploration and cartography. There is also another statue of Flinders down at his eponymous university at Tonsley Park, so the great seafarer is well covered. Not far away from Flinders on North Terrace, out the front of Government House, is the South African War Memorial. It’s big, as well as impressively stylish, but lodged at the North Terrace, King William St intersection, with its thousands of cars, trams and people, scurrying past, it becomes little more than urban wallpaper.

North Terrace is home to most of the state’s grandest monuments. The imposing tribute to King Edward VII, which sits high in the sky, with the plinth alone being more than 6m tall, has been there since 1920.

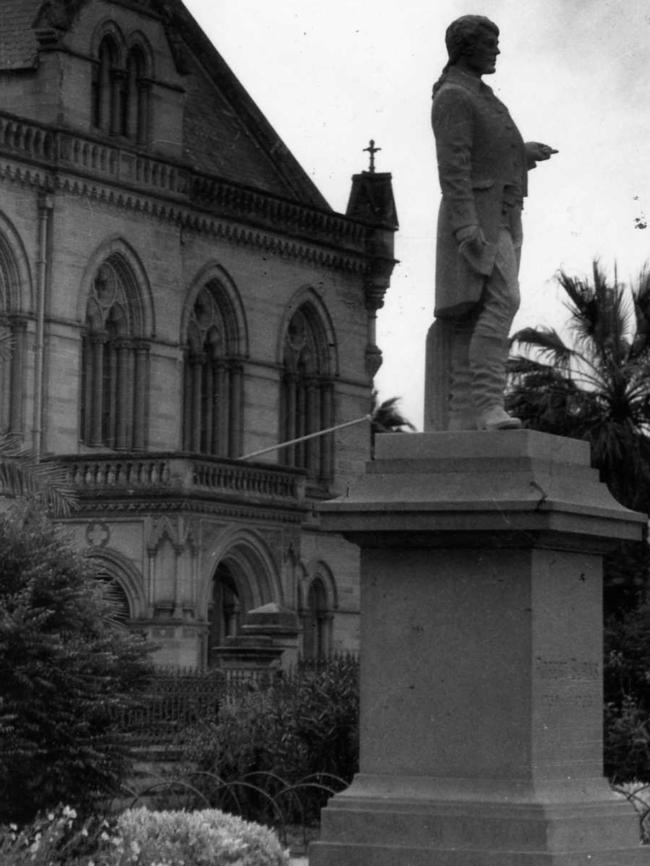

Close to Ted the seventh is the Scottish poet Robert Burns, further along, on the Adelaide University grounds we find Walter Watson Hughes and Thomas Elder and Samuel Way in a loose triangle.

Swing round to Victoria Square, we can find old Queen Vic herself (a rare statue dedicated to a woman), 19th century explorers John McDouall Stuart and Charles Sturt and South Australia’s syphilitic, shoot-em-up premier Charles Cameron Kingston. But let’s come back to him later.

As mentioned, we have Light atop Montefiore Hill, pointing down at the city he designed. Although, the revamped Adelaide Oval obscures his vision a little these days. The Oval itself has become the home of many of Adelaide’s more modern statues. If statues reflect what is important to a society at a particular point in time, then South Australia is firmly in the age of sport.

There are monuments to reflect the contributions of footballers Barrie Robran, Malcolm Blight, Russell Ebert and Ken Farmer. Also memorialised are cricketers Darren Lehmann, Jason Gillespie, Clem Hill and George Giffen. Robert Hannaford’s Donald Bradman tribute is also in the vicinity, aiming a straight drive across King William Road. Port Lincoln has a statue of three-time Melbourne Cup winner Makybe Diva on its foreshore.

There are more than just sporting figures around the Oval, however. Arguably, the most impressive statue and the strangest statue exist within a few hundred metres of each other.

There is a dignity to the memorial to the pioneer aviator Ross Smith, which stands on War Memorial Drive that seems to escape other city monuments that rely on heft alone to convey an impression of importance.

But Smith up there, wearing his flying jacket and with goggles perched on his flying helmet, is a genuine South Australian hero. Ross and brother Keith Smith, plus crew Jim Bennett and Wally Shiers flew a Vickers Vimy from England to Australia in 1919. It took 28 days, but they were the first to complete the long haul by air between the countries. Only three years later, at the age of 29, he was dead, killed in a plane crash in England.

It’s easy to see, even today, why South Australians rallied to raise money for a statue to Ross Smith, which was unveiled in 1927. The monument to the English and Australian King George V is another matter.

Perhaps, it’s because the monument came well after what could be considered the great age of statue building. George V died in 1936 and his monument wasn’t unveiled until 1950.

Stumbling across it today, it feels unloved and hidden away. It sits on Sir Edwin Smith Ave, opposite Pennington Gardens, its original bronze giving way to green, an empty bottle of cider at its base and dwarfed by an adjacent Moreton Bay fig tree with a homeless camp below. It feels like the place you would pick if you ran out of all possible spots to place a statue of another giant man on a horse.

In his book Silent Witnesses, Adelaide’s Statues and Monuments, author Simon Cameron writes this memorial to George V was “the first time the attempt to erect a royal monument struggled’’.

“Popular sentiment may have been high and the statue committee’s ambitions grand, but imperial allegiance was shifting in the commercial heartland and moneyed halls of Adelaide,’’ Cameron writes.

As a result, raising money to build the statue proved difficult. The aim was to raise 5000 pounds from the public, but it was never reached, and the state government was forced to step in to finance the rest.

Cameron writes there was “prolonged bickering’’ over choosing the eventual site. The present spot was eventually settled upon because it would align with the memorial gardens across the road to emphasise link between the Crown and Christian fellowship. A plaque was to be attached to the pedestal to make this link clear, but it never happened.

“The impecunious fund could not afford it, so the rare viewer who happens to stumble upon the statue is left to guess the reason why the late King has been banished to the back blocks,’’ writes Cameron.

Cameron hopes to write an updated version of his book. He calculates that since the book was released in 1997, another 14 monuments and statues have been added. These include ones at Adelaide Oval, plus Robert Hannaford creations such as the entertainer Roy “Mo” Rene in Hindley St, the remembrance of Simpson and his Donkey, his evocative “woman and girl” memorial in Riverton to honour the Ngadjuri landowners in the region, as well as Vietnam War Memorial and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander War Memorial next to the Torrens Parade Ground.

“The reason I got fascinated by it (statues) is because they tell you so much about the society that puts them up there,’’ he says.

In Adelaide, statues were put up as a mark of civic pride. Adelaide was a new city, a designed city with all these big, wide boulevards. There was a belief such public art could lend Adelaide a more European feel.

“Some are commemoration, some are reinforcing the morals and beliefs of the time, celebrating heroes like the explorers and the pioneers,’’ he says. “Some are pure propaganda pieces, where the wealthy Adelaide Club section of society often were very effective in memorialising themselves.’’

South Australia latched onto the early explorers such as Sturt and McDouall Stuart. Lauded for braving the fierce interior of the continent. The fate of the indigenous people wasn’t given so much as a passing thought. Yet, those early days gave rise to many confrontations and some massacres.

In the West Terrace cemetery there is still a memorial, which reads: “Monument is erected by the officers and men on the Overland Telegraph Line in memory of their comrades who were treacherously murdered by the blacks whilst in the discharge of their duty.’’ Missing the obvious point that the white men were invading someone else’s country at the time. The line was built on the route taken by McDouall Stuart in his north-south crossing of the continent.

In a perfect world, archaeologist Jacinta Koolmatrie, says “I think that they (statues) shouldn’t exist in a way’’. “The whole idea of it doesn’t sit well with me.

“Everything here is a reminder of colonialism, every statue, every building is a reminder.’’

Koolmatrie says if the statues are to continue to exist, a more-than token effort is needed to make them relevant. That simply adding another small plaque to a statue won’t cut it.

“If they could be reframed in a way that was impactful that you could see from afar so that you would question ‘why is that massive sign in front of that statue?’ Something that would make you stop and think about it rather than just passing it every day.’’

Koolmatrie believes there needs to be more monuments to Indigenous achievement, and also memorials to the massacres and brutality that marked much of the history of colonial South Australia. But, rather than singling out individuals, she believes the monuments should celebrate causes and events.

“I think too much emphasis is placed on the one person and so you are kind of placing this person on a pedestal, literally,’’ she says.

History Trust chief executive Greg Mackie is not a fan of tearing down statues. But he is also keen on finding a way to place more historical context around the ones we have. That could be through further information at the site or through the use of technology such as QR codes that visitors could scan. The Trust also has its Adelaidia app which gives information on locations and objects around the state. “I would like to think a pluralist, civilised, tolerant, democracy such as we aspire to be can make room for diverse views,’’ Mackie says.

“We shouldn’t shy away from robust debate about these things, provided we can always keep in mind that memorials serve multiple purposes. Including an educative purpose and education isn’t necessarily one perceived truth.

“Education can be about demonstrating there are perspectives that are differing perspectives about the significance of this event or that person.’’

The point being that it’s not possible to simplify all people into the categories of either being ‘good’ or ‘bad’.

In the United Kingdom, some have attempted to reduce figures as complex as Winston Churchill into a simple good/bad binary choice, with some advocating memorials to the wartime prime minister should be removed. His detractors say he was a racist, responsible for terrible atrocities in India and beyond, while his advocates turn a blind eye to his faults as if they didn’t exist. The logic being he couldn’t possibly be a racist because he led the fight against Nazi Germany.

The truth is he was both and we should be able to deal with that. The statues of Adelaide also contain such dichotomies, even if not at such a contentious level.

The seated monument to Walter Watson Hughes lurks outside the Mitchell building at Adelaide University. Hughes is lauded as a founder of the uni and its first donor. Hughes contributed 20,000 pounds. The equivalent donation today would be around $3 million.

Hughes made his money mining copper around Wallaroo and Moonta. But before he arrived in Australia in 1840 he was an opium trader, sailing his ship Hero between India and China.

A married man, Hughes also fathered a child with a full-blooded Indigenous woman known as Mary. Almost 150 years later, Hughes’ family tree includes former Sydney Swans footballer Adam Goodes, who is his great-great-great-great grandson.

In the SBS program Who Do You Think You Are, Goodes discovered Hughes was one of his ancestors. Goodes was unsettled by the revelation and the fact Hughes had fathered a son he could not acknowledge.

“He has made a lot of money off of Aboriginal lands, like a lot of white people did in those days, not being able to contribute back to the Indigenous communities to the illegitimate child that he had,’’ Goodes says in the program.

“I’m a bit disappointed obviously that our women are good enough to bed with but not good enough to acknowledge the children.

“People like Captain Hughes and others would come and take advantage of the land, take advantage of our women and then leave. Especially when it’s my land, my people, my country out there. It’s just really sad.’’

Then there is the reminder of the interesting life of Charles Cameron Kingston, memorialised in Victoria Square. The Kingston statue was unveiled in 1916, but he was such a contentious figure even then that there were plenty who objected to it going up at all.

Kingston was SA premier for six years and was a “father of federation’’ and served as trade minister in the first federal parliament. He was also a reformer. As premier he introduced bills to give women the vote and allow them to stand for parliament. South Australia was the first place in the world to allow both. He did much to improve conditions for workers.

On the other hand, he was a driving force in drafting the White Australia policy. Then there was his personal life. In 1892, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography, a parliamentary colleague, Richard Baker, called Kingston a coward, a bully and a disgrace to the legal profession. So enraged was Kingston, he challenged Baker to a duel in Victoria Square and sent him a pistol. Baker sent the police instead and Kingston was arrested with a loaded revolver.

He was tried and given what was essentially a 12-month good behaviour bond. It was still in force when Kingston became premier. His career was then cut short in 1903 when he contracted syphilis and he died from a stroke five years later.

Some societies have, of course, pulled down statues and most of the world applauded. Even many of those who now believe every Australian statue to be sacred.

When the giant image of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein was pulled down in Baghdad, the world understood. When the Soviet Union collapsed and statues of leaders such as Lenin and Stalin were removed, it seemed a perfectly natural thing to do.

It has been suggested that some controversial statues could be relocated rather than destroyed. Perhaps placed in a museum where the history can be better explained.

“Everyone is entitled to disagree with the values of a person from the past but whether we like it or not they are representative of the past and to remove them entirely can be seen as a way of avoiding an honest confrontation with that past,’’ Monteath says.

Looking at statues could, of course, be only the first step in a longer process. So much of what surrounds us has been handed down from the state’s earliest days. The street names, the towns, the rivers and mountain ranges. Why do the far inland Flinders Ranges carry the name of a seafarer? The Eyre Peninsula and Lake Eyre are named for the explorer Edward Eyre. After leaving Australia, Eyre became Governor of Jamaica in 1861. In 1865, when locals staged a revolt in 1865, Eyre put down the rebellion with such force that more than 400 people were executed.

Statues, after all, only appear immovable. The meaning of any particular statue can change over time. In fact. It’s inevitable. Society today will look at the statue of someone like Thomas Elder much differently to how it was seen a century ago.

“They create this impression of immutability that in reality monuments change,

interpretations of them change, that’s a natural state of affairs,’’ Monteath says.

Geography can change as well. The statue of Colonel Light was installed in Victoria Square before heading up Montefiore Hill. The Robert Burns memorial is in its third location.

One solution could be to erect more memorials to reflect the diversity of South Australia. The vast majority of statues are white and male.

Flinders University anthropological archaeologist Claire Smith says “there is definitely a worldwide movement and so I think we need to rethink this as part of that worldwide movement’’.

“Let’s think about who we are today and who we want to commemorate today,’’ she says. “It might be who you add. I would add Aboriginal people. I would add some of the great people who have led the immigrant community in the ’50s and the ’60s, some of those leaders.’’

It’s also about South Australian deciding what message it wants to send to itself and the world about what kind of place we are.

“This is a ‘what are ya’ question,’’ Smith says. “What are we as Adelaide? Who is Adelaide now? It’s around identity, changing identity and community.’’