Secret love could be hidden in Somerton Man’s DNA

The inside story of how an Adelaide academic and his wife – who believes she is the granddaughter of the Somerton Man – fought to solve one of our great mysteries.

Editor's note: This article was first published on February 16, 2018

The Somerton Man only narrowly avoided a pauper’s grave. His funeral was such a simple affair that The Advertiser’s crime reporter Bob Whitington and the owner of a hotel opposite the West Terrace cemetery were called in as pallbearers. No one knew who the man was and there was no one to grieve.

Seventy years later, we still don’t know who he is, but the Somerton Man is far from forgotten. Advances in science combined with the persistence of an Adelaide academic have brought us closer than ever to solving an Adelaide cold case that started when a body was found propped against a seawall at Somerton on December 1, 1948, a half-smoked cigarette on his lapel. He had been there for 12 hours or more and a man who saw him the previous evening thought he remembered seeing his arm move. A scrap of paper found in a fob pocket was printed with the Persian words “Tamam Shud”, meaning “finished”.

Over the following decades, who he was and why he died took on overtones of a Cold War thriller. Scattered words and letters in the back of a book of Persian poetry from which the scrap was torn looked like a code, which led to speculation he was a Soviet spy. One of the examining pathologists suspected poison, probably suicide or possibly murder. With an eye to future exhumation, care was taken to embalm his body.

The case, baffling and intriguing in equal measure, bubbled away for almost 60 years until a decade ago it was seized on by a curious electrical engineer at the University of Adelaide, Derek Abbott, who had an interest in cryptology, the art of code breaking. Over time he has become more and more gripped as he chased down every lead. And in an almost absurdist twist of fate, he married and has three young children with a woman who is quite possibly the dead man’s granddaughter.

On a personal note, Abbott, if slightly embarrassed at the romantic turn of events, has never been happier. “I don’t want people to think I’m some kind of nutter,” he laughs.

He met Rachel in the course of his research and she is now at home dealing with the unexpected mayhem of their three children under five, including twins. “I’m a train wreck, it’s lovely,” she says.

They met in 2010 when he contacted her in Queensland to send her a copy of an S AWeekend article, published in 2009, about assigning his PhD students to use computer software to solve what was then thought to be code, a theory he later ruled out. They met in person some time later and by the end of a week had decided to get married. “In terms of personal stuff, it’s given me a new family basically, one that I love dearly,” Abbott says. “As a scientist, though, I was pursuing the case already and I still am, so nothing much has changed. I’m still passionate about finding his identity and I’m still dispassionate towards the underlying science that goes into that.”

Abbott is this year embarking on a renewed mission to have the dead man’s body exhumed in the hope that we can finally know, 70 years later, who he was and possibly why he died. This time the landscape is different because lingering sensitivities about an Adelaide nurse whose phone number was found written in the man’s book of poetry have died with her. More urgently, the man’s possible granddaughter, Rachel, is arguing for her right to know if he is her grandfather, and who he was.

“I would like to resolve it, we would like closure and we definitely want to exhume the body,” says Rachel. “It seems to me there is evidence that the Somerton Man is my grandfather. He may not be, of course, but the fact is you have two very strong genetic traits, so the odds of him not being related are unusual.”

A new submission to Attorney-General John Rau, requesting permission for exhumation, will this time include a petition demonstrating public support and will have the backing of some respected public figures, including a former attorney-general and Labor elder statesman Chris Sumner, who has advised Abbott in the preparation of the submission.

“In my view, it is in the public interest for the exhumation to go ahead,” Sumner says. “It is still technically a cold case that was never actually solved and it would be assisting police at least to close the case.”

The founder of the Adelaide Festival of Ideas, Greg Mackie, is also keen to see it resolved for the sake of the man’s potential descendants, as is the chair of the South Australian Museum Jane Lomax-Smith, a pathologist, who says the case carries considerable public interest.

“It may not be Richard III but this is a significant piece of Adelaide history and one which science could solve,” she says.

Abbott says exhumation would provide irrefutable information about the dead man – from DNA extracted from a tooth or inner ear bone, to a bone isotope test to establish his country of birth and analysis of teeth and bones for clues about his habits and lifestyle. Liver abnormalities detected under microscopic examination in 1949 could potentially be analysed and a ruling made on why he died. “It will give us some tantalising clues and may help in eliminating some possibilities,” Abbott says.

But he is nervous. Rau has knocked him back before, most recently in 2011, saying there was insufficient public interest and not enough “stakeholder support” – public service terminology for support from people with a direct line of interest into the case. He hopes to counter that this time with the 7000 signatures, the support of potential relative Rachel and the lack of solid arguments in favour of another rejection.

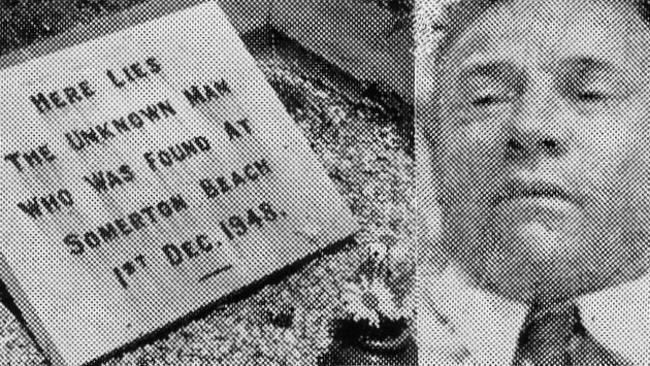

He wants it known that the exhumation would be at no public cost. The funeral home that carried out the burial in 1948 – in a grave whose headstone reads “Here Lies The Unknown Man Who Was Found At Somerton Beach” – is so fascinated that it will do the disinterment and reburial for free. The subsequent tests would all be done at the University of Adelaide’s Centre for Ancient DNA and the university supports Abbott’s work, although as an institution it does not back one side or another.

There is another, smaller potential breakthrough under way. Abbott has in store multiple single strands of the man’s hair, which were embedded in a plaster death mask made before his burial. DNA extraction was tried and failed four years ago, but techniques have advanced to the point where some identifiable genetic material was retrieved. Three hairs are being analysed at the University of Adelaide’s DNA lab and the results have provided a mitochondrial DNA profile that shows from which gene group his mother came.

Importantly, it confirms viable DNA can be retrieved from the body, which bolsters confidence in the value of exhumation. But the hairs are not an answer on their own and will not yield a full DNA sequence. “At best it will give us partial information that may bring us closer to understanding more about him,” Abbott says.

He is wary about saying anything about his connection through marriage to the case because his passion for the science has driven him this far and it is still his motivation. He thinks the 70th anniversary of the man’s death is the perfect time to give the man his identity back, particularly now that DNA testing has become much more commonplace. A full DNA profile, once obtained, could establish or eliminate the man’s connection to Rachel and DNA databases would be searched for close matches to find a common surname, which would solve the mystery of who he is.

“Knowing how he died is, in a sense, the least important thing,” Abbott says. “It’s more important to know who he was, not only for my wife’s family so they know potentially who they were related to, but because he must have his own family and they are missing somebody.”

Having abandoned the idea of codes and cryptology, Abbott is now convinced the mystery is far more banal. He believes the man’s connections with the local community, in particular through a woman called Jo, were concealed to avoid the shame of disclosing a baby born out of wedlock.

Rachel’s lineage is complicated over two generations. She was born in Wellington to Australian parents who were both dancers with the New Zealand ballet company and she was given up for adoption to a New Zealand couple who never told her she wasn’t theirs, although she had her suspicions. “I looked very different to most of the others in the family,” she says. “I just had this feeling.”

In her 20s, she received a letter from her biological mother, Roma, who wanted to make contact, but wanting not to upset her adopted mother, she did not follow it up. Much later, on holiday on the Gold Coast, she wrote a card and finally met her mother, the dancer. She spoke by phone to her father, Robin, and met him once. “It was uncanny because I was obsessed with dance as a child,” she says.

Her parents had married but divorced, and she never met her presumed grandfather, Robin’s father George, before he died. But she met her Adelaide grandmother, the nurse Jo Thomson, whom she found an interesting, unusual woman who was witty and smart but also solitary and prone to melancholy periods.

“One of the first things she said was ‘if you’re wanting a grandmother, that’s not me’,” she says. “She wasn’t your typical granny in the rocker knitting.”

If Abbott is right, Jo Thomson, who died in 2007, had an affair with the Somerton Man, resulting in a child, the ballet dancer Robin, who was Rachel’s father. Robin, who was born in 1947 and died in 2009, grew up with Jo, his biological mother, and knew his father as George, the man Jo married in 1950, three years after Robin was born. He was passed off as George’s child, but Abbott believes Robin’s real father was the Somerton Man.

Some time after the man’s body was found, a copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam was found in the back of a car at Glenelg. It was the same Rubaiyat from which the scrap of paper was torn, and on the back cover of the book was written Jo’s phone number.

Police visited her at her home in Moseley St, Glenelg, about five minutes’ walk from where the body was found, but she said nothing. In a later interview she was shown the man’s death mask and again denied knowing anything. But the man who made the mask, Paul Lawson, told Abbott and others she averted her eyes from the mask and stared at the floor, and, at one point, looked ready to faint. In the five years before her death, she admitted to friends she was the nurse whose phone number was found in the man’s copy of the Rubaiyat but denied having known him or how her number got there.

“It all adds together,” Abbott says. “At that period of time it makes sense in terms of the big secrecy, the hush-hush. We look at it with our modern eyes – what’s the big deal? – but a child born out of wedlock was a big deal in those days, so you can’t blame her.”

Adding weight to this theory are some very unusual physical characteristics the dead man shared with Robin Thomson, Rachel’s father. One is a dental anomaly of absent incisors, a rare genetic trait. The inquest into the death of Somerton Man recorded the incisors were missing with no gaps, meaning his canines grew next to his front teeth. In photographs of Robin, the same trait is visible.

There was another unusual anomaly involving the shape of his ears. Abbott confesses he stared at the photo of the dead man and thought there was something odd, although he could not say what. He showed the image to an anatomist and asked if he noticed anything. “He said ‘yes, these are very rare ears’. He said ‘your ears have two hollows and the upper is smaller than the lower, but in the Somerton Man they are the other way around – his ear has a very large upper hollow and a small bottom’.”

Abbott tracked down a photo of Robin and found his ears were the same, an unusual and accidental finding that convinced him he was on the right track. It firmed up his belief that the letters scrawled in the poetry book once thought to be a Communist cipher were incidental, and the scrap of paper with the words “Tamam Shud” – ‘finished’ – was best viewed as a sad lover’s note.

“I think we have the makings of a very good hypothesis that Robin Thomson is the son of the Somerton Man,” Abbott says.

The odds of this are strong, but they will never be more than conjecture without the State Government allowing the independent arbiter, science, to confirm the facts. Through DNA, Abbott most of all wants to give the man his name back. There may be brothers and sisters or their descendants who would want to claim him seven decades later, like soldiers from lost wartime graves who are matched to their families through DNA and brought home.

“I see this as a similar thing, that we exhume him, we DNA test him and we bring him back to his original family,” Abbott says.

Once the DNA is in, a familial connection with Rachel through Robin could be confirmed. Rachel’s DNA is already posted on to international DNA websites such as Ancestry.com and 23andMe, a privately owned genomics and biotechnology company used by people trying to trace family connections. For a $99 fee, you send a DNA swab, which goes into a sealed database. Anyone with a familial match of up to a fifth cousin removed can access your profile and get in touch, making it a kind of Facebook of DNA.

Abbott has long suspected the man was American, because of the clues provided by the contents of his pockets and his clothing. He carried a slim aluminium comb, which was American, and his tie was American based on the direction in which the stripes ran.

Abbott, who dipped into the history of tie making for his research, learnt that in the 1920s American manufacturers bought tie fabric from the UK, but to avoid accidentally manufacturing a proprietary style – an Eton tie, for example, made by mistake – they ran the stripes in the opposite direction.

The path is littered with clues but, like the cryptology theory that had fervent followers for a time, nothing can be known with any certainty without exhumation. Bizarrely, one of the key people whose support could help or hinder the new bid for exhumation has nothing at all to do with man, or the case.

Back in 1949, a hat was passed around among bookmakers who drank at the Elephant and Castle, across the road from the West Terrace Cemetery, to save the man from a pauper’s funeral. As a result, the name on the burial licence was the SA Grandstand Bookmaker’s Association. In more recent times, the now SA Bookmaker’s League was contacted when the lease was due to expire and it paid to renew it.

The league’s chair, Warren Barrington, is not sure about exhumation and wonders if it makes a better story to leave the man’s identity unknown. He has met Abbott and told him the matter will be discussed at the league’s next meeting, where it will decide whether or not to object. They have objected in the past, following the advice of a retired policeman who wrote a book about the case, Gerry Feltus.

“The reason I got through a third party, not from Gerry, was that people would get hurt by it,” Barrington said. The “people” he refers to is Jo Thomson, Rachel’s grandmother, whose potential for hurt over the possible disclosure of her son’s parentage died with her in 2007.

Feltus says he has supported exhumation in the past, but he dislikes Abbott and appears to resent his avid pursuit of the case, accusing him of self-interest. He dislikes Abbott’s enthusiasm and claims Abbott uses his Somerton Man website to spur things along.

“The Attorney has said before he won’t allow it, but Abbott won’t accept it, he just keeps on pushing,” Feltus says. “It is purely an exercise by Abbott and now his wife, who will agree to anything, sign petitions or whatever, and it’s all for him. He couldn’t give a shit about the Unknown Man.”

Leaving aside his feelings about Abbott, Feltus says he originally wanted the body exhumed as it could give information about his cause of death. “I thought there might be chance with modern technology that they might be able to identify any poisons in his body,” he says.

He also said concerns about formaldehyde and potential DNA contamination during preparation of the body made him think it would prove nothing. But the recent successful extraction of DNA from the death mask hairs has demonstrated that not all DNA was harmed by the embalming.

“My only thing against it is that Abbott is using it purely for the reasons the Attorney-General saw through, that is because it’s exciting. It’s one of his favourite words, exciting,” Feltus says.

Abbott is mindful his new exhumation bid could be derailed by Feltus, or by Barrington under the influence of Feltus. He knows his marriage to Rachel leaves him open to suspicion that his work on the case is an obsession and he is at pains not to use his marriage for leverage.

He was passionate about the case before he met her, and he only met her because of it, he argues. Most of all, he wants science that was unheard of 70 years ago to be allowed to hold sway and end the speculation.

“I don’t want to see a bid for exhumation stalled again for no good reason, so let’s try once and for all to solve this Adelaide mystery,” Abbott says. “Civilised societies always strive to preserve or discover the identities of their dead and I think we owe it to ourselves and our history to find out who this man was.”

Editor's note: This article was first published on February 16, 2018