Without coral and clownfish, can environmentalists make us care about the many species they say are at risk from oil drilling in the Great Australian Bight?

For a few minutes all eyes are locked on the enormous creatures. But it’s a cameo performance. With a flick of their giant tails, they’re suddenly both gone, back down into the deeps off Esperance at The Bight’s westernmost end. They can travel kilometres before resurfacing. We won’t see them again.

The spectacular scene may have been short-lived but for the crew of the Greenpeace flagship Rainbow Warrior III it’s a reminder of what they’re fighting for – the sea creatures who live in an ocean home that environmentalists fear could be ruined if oil drilling is allowed to go ahead in the Great Australian Bight.

The whales are the most obvious symbol of this underwater world, but there is a vast number of other species beneath these waves – it is just that they don’t have the star power of the massive cetaceans.

For the past two days the 15-strong crew and an assortment of passengers have spent every minute of daylight scanning the horizon for just a glimpse of a whale – either from the several species known to frequent the area, or others which may never have been seen there before.

Sonar can make the search for these giant marine mammals easier but a piece of A4 paper taped to the helm commands “No Sonar for Whales”. Binoculars and telephoto lenses will have to do. Whales and human sonar technology don’t mix.

Local whale watcher Paul Cross, who owns Bremer Canyon Killer Whale Expeditions, says the presence of birds or other sea creatures are good signs of where to look. Seals can be a good sign, too, as can smaller whales.

A day earlier a beaked or grey whale was spotted by one of Cross’s boats, and there were high hopes of seeing killer whales that have relatively recently been discovered in the area. We never saw any, but the sperm whales were good enough for the excited Greenpeace crew and their guests.

The Bight is now the focus of a fierce debate that pits economy against environment. At issue is what might be billions of dollars worth of oil deep beneath its vast, wild waters. Equinor, a Norwegian energy company, has become the latest suitor to set its eyes on this potential treasure under 2.2km of sea and 2.7km of sediment in the Ceduna sub-basin, about 372km offshore and 475km west of Port Lincoln.

The plans have galvanised resistance, uniting the likes of Greenpeace and the Wilderness Society, state Labor MP Leon Bignell, federal independent MP Rebekha Sharkie and Greens like Sarah Hanson-Young and former Greens leader and still active campaigner Bob Brown.

They argue that drilling in the remote, near pristine and little understood environment around The Bight risks a repeat of the 2010 Deep Water Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico off the US. But if it happened here it would happen in an environment critical to the health of multiple species of migratory whales, as well as important commercial fisheries for prize fish such as the bluefin tuna.

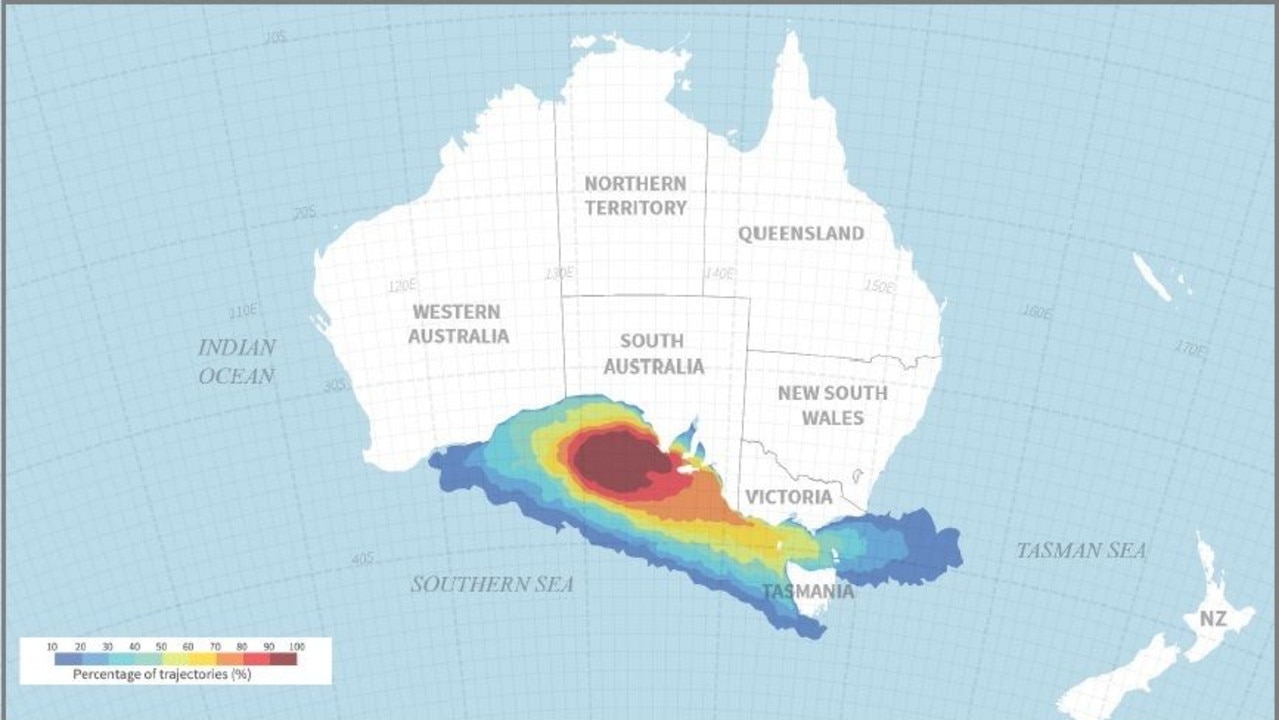

The cost of any clean-up could wipe out any economic benefit from the oil – the slick, they say, would reach from Albany in Western Australia around the entire Tasmanian and Victorian coastlines into waters off southern NSW.

The industry – and so far regulators – believe it can be done safely, including the seismic testing in the exploration phase. That would see sub-sea explosions to allow sonar technology to map the ocean floor in search of the oil – but also, say opponents, hurt or kill sea creatures.

But as Equinor became the third oil company to turn its attention to The Bight (both BP and Chevron have explored the idea before resolving to look elsewhere), Greenpeace set its sights there too, and sailed its flagship, usually ported in Amsterdam, here late last year to support the environmentalist cause.

On-board, Greenpeace campaigner Charlie Cox points to a crucial problem for the campaign: it does not have a well-known rallying point like the Great Barrier Reef with its kaleidoscopic coral and fish. And yet, scientists say, The Bight does have its own version – the Great Southern Reef.

Some scientists have been trying to make the case for its wider recognition, as it has not even got an official name.

“The Great Southern Reef does not stand out in people’s minds as something connected, magnificent, unique or valuable in the same way as other iconic ecosystems, such as the Murray-Darling or the Great Barrier Reef,” says Dr Thomas Wernberg from the University of Western Australia told Australian Geographic.

“Identity is a first and essential step in establishing a presence that people can relate to and care about.”

The reef stretches from WA around the south of the continent to northwestern NSW, covering 8100km of coastline, its rocky (not coral) reefs home to vast kelp forests and weedy seadragons, starfish, urchins, shellfish, sponges and an enormous list of fish species. It reportedly has more biodiversity than the Great Barrier Reef, and supports abalone and rock lobster industries worth $500 million.

Greenpeace agrees the reef needs to be better appreciated. “We know that when anything happens with the Great Barrier Reef all of Australia, all of the world, is up in arms wanting to stop anything bad happening to that part of the ocean,” Cox says.

“We want that same status down here. There’s a huge reef along the southern coastline called the Great Southern Reef, and every time scientists do more research here they’re finding new species. It’s more biodiverse than the Great Barrier Reef and 85 per cent of the species are endemic, meaning they’re not found anywhere else.”

The problem, she says, is most people don’t know that, or that seismic “blasting” used to explore the ocean floor damages sealife. With Rainbow Warrior III, Greenpeace hoped to change that.

“The ship is a really big and awesome resource that Greenpeace does have … and bringing its fame to shine a light on this part of the ocean is really critical for this campaign,” Cox says.

The ship is crewed by a mixture of employees and volunteers, and SAWeekend was invited on board for part of the trip. Its captain, Hettie Greenan, is one of several Greenpeace captains who take turns helming the vessel. She, along with most of her regular crew, hail from all over the world and spend about three months at sea before returning to Ukraine or France or, in the case of one volunteer, Seacliff in Adelaide.

They all have roles critical to keeping the boat running – some are engineers or radio operators, some are cooks, and some are full-time campaigners and media communications specialists.

Each morning, except on Sunday, they set about cleaning every bit of the ship, which is usually under sail except for when it legally must use diesel engines to enter some major ports.

Meals are served three times a day, and meat and fish are a rarity. The crew generally subsists on a vegan diet with the exception of one day a week when meat is on the menu for those who want it. Boiled eggs supplement the meals for the crew who can’t quite embrace veganism, even if they do believe in its environmental benefits.

Those not tasked with running the ship are running the campaign and might also be found on its upper level in a meeting room tucked behind the bridge. This is where the planning and execution of the open days, like one held at Port Adelaide, or the flotilla protest at Port Lincoln in January, were thrashed out.

There’s just a strong enough Wi-Fi signal on board for them to do their work – though you’ve got to pick your spot carefully because it struggles to penetrate the steel walls.

These campaigners often don’t spend the same long months at sea as the regular crew though, so might reliably be found on the ship’s helideck – now largely disused following the invention of affordable drones – trying to stave off seasickness. There are no energy hungry gyro-stabilisers to combat the stomach-churning pitch and roll on this ship.

On the lower decks are the mess and recreation room, where visiting media are swiftly informed that the use of mobile phones or cameras will result in a fine – payable in the form of a carton of beer to the ship’s bosun the next time the crew goes to shore. This is supposed to be an important time for socialising and relaxing – even long weeks at sea are no excuse for gazing at a screen during dinner.

As the 57m diesel-assisted sail boat pitched and rolled through The Bight – along a similar route to some of the whales it came to speak for – the ship stopped at Kangaroo Island to help South Australian scientists launch submersible vehicles to investigate the sea floor. Scientists are commonly invited aboard. For voyages like this, campaigners contact universities and research institutions which struggle to fund environmentally focused research.

Marine ecologist Sam Owen boarded the Warrior from South Australia in December to dive and launch a remote operated vehicle to explore the environment hidden under The Bight.

“The great thing about these expeditions is that we were able to visit remote islands and reefs that are only accessible with a large vessel like the RW,” Owen says.

“The sites we dived from Eyre Peninsula to Ceduna including Greenly Island, Perforated Island, Pearson Island and the Nuyts group were spectacular and stand out for me as my favourite dives in 13 years of diving in SA. Because these areas are so inaccessible most people have no idea we have these spectacular underwater environments in our own backyard.”

The Rainbow Warrior’s travels through South Australia’s section of The Bight attracted plenty of attention from locals who seemed to have a big interest in finding what lurked in that backyard though.

Hundreds boarded the shipduring open days at Port Adelaide and Port Lincoln. It pulled in at Ceduna to rally the support of concerned locals there. Even at Port Lincoln, whose economy relies on bluefin tuna (an industry Greenpeace has “red-listed”), hundreds welcomed the ship to oppose drilling in The Bight.

Whale watcher and guide Paul Cross says coastal communities are terrified of the prospect of oil drilling trumping tourism and fishing when the loud voice of resources companies drown out those smaller businesses. The flotilla of hundreds of small boats at Port Lincoln back him up.

Tourism around whales and fishing charters is worth billions, Cross says. But the industry is populated by small independent operators who struggle to be heard. That’s why they have opened their arms for Greenpeace, he says. “It’s just insane,” Cross says of the oil industry plans. “The risk of anything going wrong is just too big.”

Before drilling ever takes place, he says, the “blasting” from seismic testing will damage everything from sea grass to the migratory whales.

The oil industry disagrees. Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association calls the economic potential of Bight drilling a “game changer” that could see 1500 jobs, millions of barrels of oil and billions in tax revenue generated over the next 40 years.

The exploration companies insist seismic testing won’t hurt the environment, and regulators have given them the green light to search on that basis. Other proponents point to the lack of catastrophes from oil exploitation in the Bass Strait over many years as evidence it can all be done safely.

But Greens elder statesman Bob Brown believes The Bight debate, protests against the Adani coal mine in Queensland, and the recent fish kill disaster on the Darling River at Menindee, have all galvanised renewed support for environmentalism.

“I think we’re (the movement) in a resurgence,” he says. “These people are here to make a stand and it’s going to get bigger if politicians don’t listen. People feel they’ve been dudded by Prime Ministers who stand up in parliament holding coal.”

Aboard the Rainbow Warrior III, the focus of the crew is to find a way to build public knowledge of The Bight’s unique environmental properties.

Other guests include Australian children’s author Alison Lester and her husband Eddy, both experienced seafarers and nature lovers. Lester was invited in the hope a visit might spark inspiration for a new book that would help instil a reverence for The Bight or a slab of positive PR for Greenpeace in a new generation. Nature, especially coastal nature, is a regular theme in Lester’s books, which include Magic Beach and Noni the Pony.

“I think it’s most likely that I’ll do a book about the Rainbow Warrior but it won’t be until next year,” she says. “I think kids all around the world will love the stories of people fighting to save the planet.”

Heroes are always helpful in attracting attention to a cause. Little lost Nemo the clownfish made the Great Barrier Reef a bigger star than it already was. Unfortunately the leafy seadragon and other unique creatures of the Southern Ocean have yet to hit Hollywood. And some of The Bight’s potential stars aren’t the most attractive.

A day before the sperm whales made their brief appearance, University of Western Australia academic Sahira Bell spotted something even more unusual.

“Forget the whales,” she shouted. “Do you have any idea how rare that is?”

The marine life expert had spotted a sunfish off the side of the ship. It’s an appallingly ugly creature. But to Bell, who studies underwater oddities from the Southern Reef’s seagrasses to its fish, it summed up why she was on board.

“They’re so rare in the Southern Ocean,” she enthused. “So there’s lots of research on tropical populations but not much on temperate (ones). I think the sunfish could just be used as a further example of just how diverse this (Great Southern) Reef is.”

A clownfish helped make Disney nearly a billion dollars at the box office. But it remains to be seen if sunfish, seadragons, migratory whales and an array of other hard-to-find sea creatures can outsell a billion barrels of crude oil on the Southern Reef.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Adelaide’s pioneering bid to end homelessness in the CBD

A new move to learn the names and stories of the homeless is driving a bid to cut Adelaide’s rough sleeper numbers to effectively zero. Roy Eccleston reports.

From YouTube to big screen: Adelaide’s car prankster’s directorial debut

They are the Adelaide brothers who became billion-view YouTube stars after an underwater car stunt gone wrong. Now the RackaRacka duo's debut feature film is about to hit the big screen at a gala event. Read their incredible back-story.