SAWeekend: WWII Digger Malcolm Williams reflects on his time in the Middle East and Kokoda

The Japanese surrender in August, 1945 sparked celebrations in Australia, but Malcolm Williams was more worried about learning to walk again after copping a bullet to his leg in New Guinea

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- One in a million: The defining moments of WWII

- Family hails justice for Teddy Sheean after long campaign

- ‘A cover-up’: POW massacre relatives welcome Anzac360 film

- Latest rewards and offers for digital subscribers

It may be 75 years ago but Adelaide resident Malcolm “Mal” Williams remembers Victory in the Pacific Day, August 15, 1945, as clearly as any other over the four years of his World War II service.

While people were out in their millions on the streets in Australia to celebrate victory in the Pacific, Williams felt a surprising lack of euphoria. He had lost too many mates.

Not that he was in any position to party, as the then 25-year-old was holed up in a scruffy field hospital in New Guinea – and not for the first time. Several times, over three years, he’d been patched up and sent back to the grim frontline.

For him, the Japanese surrender meant it was time to get back on with life as best he could – but first, after taking a bullet in the leg that smashed bones and shredded muscle, he had to learn to walk again. It took him nine months.

There was no hero’s welcome home back in Australia. Not that the modest man, born and raised in the inner western Sydney suburb of Abbotsford, would have wanted one.

“I came back as I went, I’m not one for all this hero business,” he says in his matter of fact way.

“You go and do a job and you do it well … if you don’t want to go that’s different.”

Williams wanted to go to war all right – he was from a proud family line of soldiers, including his father, Bob, who served in both World War I and World War II.

Mal Williams trained with the army for several months in both 1938 and early 1939 but he was rejected three times when he tried to enlist.

“Everyone knew a blue was coming and they wanted us as ready as we could before war was declared so they gave us what they called universal training at Narellan army camp,” he says.

“I felt as ready as anyone to enlist but when I went up to St Martin’s Place (Sydney) to sign up they told me I was too short and too light.”

Williams was just under the army’s regulated minimum height of 5’ 6”, or 167cm, and weighed just 54kg.

“I couldn’t believe it – I thought what a waste of all that bloody training. They could have told me earlier.”

About a year later, the army changed the regulations and Williams enlisted on May 21, 1941, nearly 18 months since he first offered his services, and a fortnight before his 21st birthday.

The Australian 2/2 Infantry Battalion had been taking a terrible battering from the Germans in Crete and Greece, and when a recruitment officer came looking for replacements, Williams and a few mates volunteered, joining 16th Brigade.

Army life began with a touch of unexpected comfort and glamour as their trip to the Middle East was aboard the former luxury cruise liner the RMS Queen Mary, transformed into a troop transporter for the war effort.

Not far out from the Australian coast the sentries on board spotted an unwanted escort – an enemy submarine.

“There was this submarine which we couldn’t tell if it was German or Japanese, but the way it was behaving we knew it wasn’t one of ours,” Williams recalled.

“I was on the front of the ship and what I remember is the nose of the ship lurching up and we took off like a motor boat. She couldn’t half motor, the Queen Mary, and this sub had no hope keeping up.”

Soon after disembarking at Port Sawfiq, an Egyptian port at the southern boundary of the Suez Canal, Williams was on his way to Syria to fight an alliance of Germans, French Foreign Legion and the Vichy French as part of Operation Exporter.

He might have been the smallest bloke in the Battalion but he had a big job as a Bren gunner and a constant part of his pack was a 10kg machine gun.

“I remember arriving in Syria and them telling us to dig in … well it was all shale, not sand, and you couldn’t dig in very far,” he says. “You felt very exposed.”

After the searing heat of Egypt, the troops also had to deal with one of the coldest winters in Syrian history, when the temperature plummeted to below zero every day.

“They sent up an Indian brigade to help us out and a number of the poor devils died straight away – it was just too cold for them,” he says.

The operation successfully stopped an attack on the Suez Canal, a vital strategic target, and when the Japanese entered the war in December 1941, the 2/2 were among those troops detailed to return to defend the country.

But things didn’t go entirely to plan, The 16th Brigade was caught up for five months in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), defending the island from the Japanese. In July 1942 the Diggers finally continued their return journey to Australia.

These weren’t hills like I knew, they were bloody mountains

Less than a month after returning to home soil and they were back on board a ship, headed north.

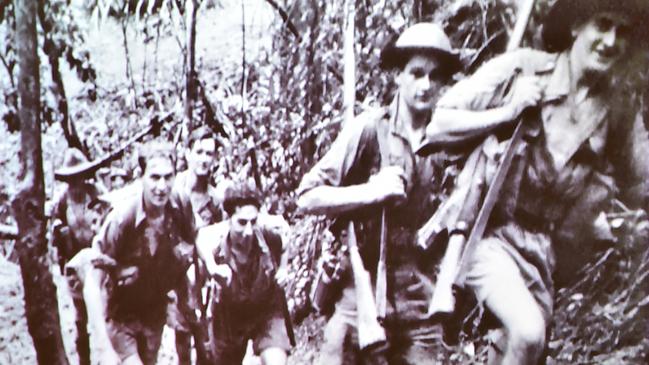

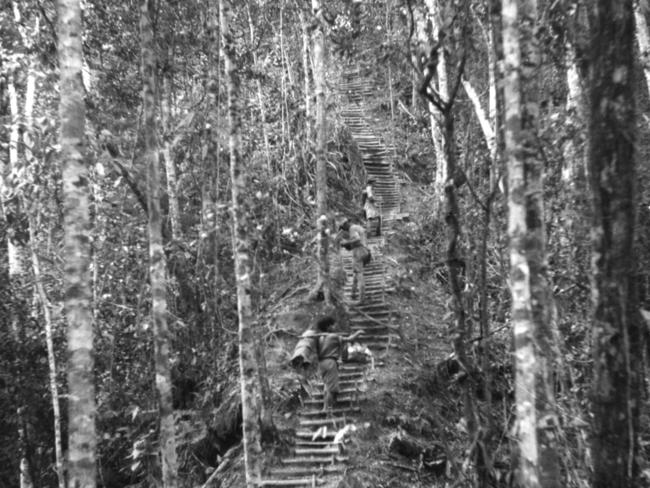

Within six months, Williams and his mates had gone from fighting in the desert of the Middle East, in the cramped chaotic streets of the Sri Lankan capital and then the terrifying hand-to-hand combat of the steaming jungles of New Guinea. In New Guinea, they fought first on the Kokoda Track campaign and later around Aitape – Wewak. Conditions were tougher than anywhere he’d ever known.

“They said we’d be fighting in the hills but these weren’t hills like I knew, they were bloody mountains,” he says.

“The tracks were only three-foot-wide and were often three-foot-deep in mud and you’d be slipping and sliding all day long. Your foxhole (defensive post) was always full of water because it never stopped bloody raining.

“The odds of survival weren’t very good as they (the Japanese) had five men for every one of us.

“We were getting beaten up badly at first. A company (150 soldiers) got knocked back to a platoon (50 soldiers) and pretty soon platoons were reduced to sections (between six and 20 men).

“If you got injured they patched you up and off you went again.”

He has total respect for the enemy he fought. “The Japanese had an incredible ability for camouflage,” he says. “We didn’t see them half the time.

“You had to check out every bush in case it started moving. They used to hide in the trees and tie themselves in as a tactic. You didn’t know if they were dead or alive so you could waste a lot of bullets trying to kill someone who was already well dead.”

There is no false bravado – he fully admits to being permanently terrified but the comradeship and dark humour of his unit helped him through.

“If you didn’t have fear you’d be guaranteed to get killed. Bert Chowne (posthumous VC winner) was one of ours that you knew wouldn’t make it as he never showed any fear.”

Williams has several remarkable grisly tales of survival including a corporal who was coming back from a patrol when he was shot through the back of his neck. The bullet finished lodged on his tongue and he was more concerned by the blisters that welled up on his tongue than the gaping hole in his head.

Another mate, shot and injured, didn’t know what had happened to the bullet until decades later when he went in for a heart operation and the surgeon found it and handed it to him as a trophy.

Most remarkable of all is the yarn of his great mate Georgie White who was sent out to relieve a soldier sitting in a foxhole at a forward listening post.

“They only had one rifle between them and this bloke he had to relieve had dropped the rifle in the mud. It was useless,” he says.

“As Georgie was setting about cleaning it this big Mongolian officer snuck up on him. When Georgie looked up he shot him up through the nose. He was left for dead but it turned out the bullet had entered his head, gone right around and lodged in the back of his skull and he survived.”

Back in Australia, White and Williams remained best mates.

“One day I went around to see him and George’s wife urged me to tell him to go to the doctor – she said, ‘He’s not himself’,” Williams says.

“He wasn’t having it but I said, ‘You’re not bloody right, Georgie. Have you looked in the mirror?’ The bullet had moved and was sticking out almost sideways.”

They drove straight to the doctor’s surgery, where White died in the doctor’s chair.

“They were the best mob of blokes you could ever meet, the men of 16th Brigade,” Williams says.

“Even members of your own family might think twice about saving your life before theirs – but not these blokes.

“The bloke on either side of you were like a part of you. That’s why the friendship of a soldier goes on for life … no ifs, buts, or maybes.”

It was a truly terrible time; kill or be killed and that’s all you need to know

Back in Australia, Williams left the army just before Christmas 1945. He married his sweetheart, Olive, soon afterwards and they had two children, Marilyn and Garry. He worked as a mattress maker and a French polisher until he retired in his 60s.

Even today, at every change of season, he gets a reminder of his time in PNG with a malarial attack that can last several days.

He and Olive, who died in 2014, moved to Adelaide about 10 years ago to be closer to family and he still lives independently in the unit they bought at Reynella East.

He reckons one the secrets for his long life can be found attached to a wall in the garage. It’s a bike he bought in 1935 with a down payment from one of his first pay packets.

“It’s a proper racing bike that Snowy Wilkinson owned when he used to race Sir Hubert Opperman in the Goulburn to Sydney races,” he says indicating a proper cycling enthusiast.

“I bought it for 14 pounds – and it took me three and a half years to pay it off.”

He rode it every day until a recent spell in hospital after his wartime leg injury flared up.

Now, he’s learning to walk all over again. “He’s very determined that he will and I don’t doubt him,” his daughter Marilyn says.

The Williams’ history of service continues with two grandchildren in the military, including naval officer Tracey Freeman, who as Tracey Mosley won Olympic medals at Athens (silver) and Beijing (bronze) with the Australian softball team.

“The same time as I was entering the archives of the Australian War Memorial my granddaughter was entering the Sporting Hall of Fame,” Williams says with glowing pride.

He’s happy to share his war experiences with each generation of his family – and they are happy to listen – but becomes emotional at the thought of them.

“It was a truly terrible time; kill or be killed and that’s all you need to know about that side,” he says softly, losing his spark for the first time in our interview.

“But I look at this way … someone had to do it … and if someone didn’t do it … we’d have no country. And we do need to remember, because that’s the only way we can hopefully stop it happening again.”