SAWeekend: The Beaufort bomber crew who might have dropped the last bombs of WWII

It started as just another mission, but by the time they returned to base the war was over. A true story of the SA bomber pilot, his tight-knit crew and one of the very last missions of World War II

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- One in a million: The defining moments of WWII

- Return to the death railway: Veteran uses VR for first time

- ‘A cover-up’: POW massacre relatives welcome Anzac360 film

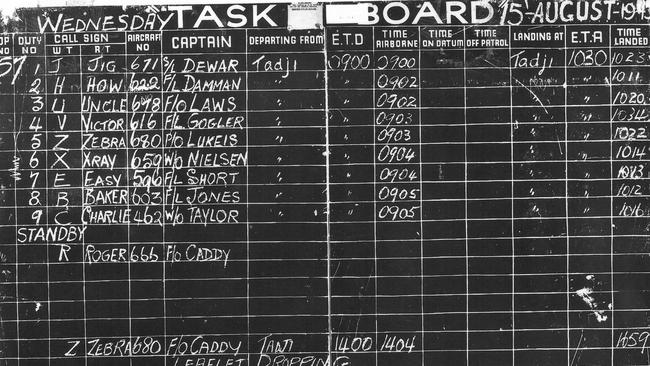

The day started just like any other. Flight Lieutenant David Jones crawled out from under his mosquito net at the remote, insect-infested tropical airstrip which had become his temporary home. After emerging from his tent, the 23-year-old South Australian pilot checked the task board to confirm the day’s mission.

Jones and his trusty Beaufort bomber 603 – christened Cock O’ The North by the crew – would take off at 9.05am on another raid targeting the Japanese troops, who continued to thwart Australian progress in the wild, rugged mountains of far northwestern New Guinea.

As always, he would be joined in the twin-engined fixed-wing bomber by his navigator, who also acted as the crew’s bombardier, wireless operator and tail gunner. They were a tight quartet and would go on to become lifelong friends.

Today, as usual, they would be part of a nine-plane mission sent out to move the enemy from a ridge at co-ordinates provided by Aussie soldiers on the front line.

“We would take off as a squadron in loose formation (in sight of each other) and head off to our target,” Jones would later recall.

“As we approached, the army would fire smoke bombs on to the target and then we had to bomb the area. After all had dropped their bombs we would strafe the mountainsides and fly over the army and drop the magazines and newspapers.

“I used to marvel at them (the army troops) as the only way they could get to their positions there was to walk up and down mountains, carrying almost everything with them.

“They would eat and sleep in the open whereas we (in the air force) would fly back to a shower, a good meal and a tent with a stretcher complete with a mosquito net.”

Today’s mission, which started and finished at Tadji – their airstrip base near Aitape on the New Guinean north coast – was a success. And nothing was out of the ordinary until the crew was on its way back to Tadji, when the news came through on the radio that the war was over.

The Japanese had surrendered. Jones and his crew might well have dropped the very last bombs of World War II.

It was August 15, 1945 and Australia had been at war for six years.

On September 3, 1939 Prime Minister Robert Menzies famously performed his “melancholy duty” and informed his countrymen that, as a result of Great Britain declaring war on Germany, Australia was also at war.

A few months later Aussie troops set sail to join the Allied forces in conflict against Nazi Germany and fascist Italy.

Just like its grotesque curtain raiser 25 years earlier, the conflict in Europe was ubiquitous. It was death and destruction on an industrial scale.

For Australians, the horror became even more real in late 1941, when expansionist Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and started a seemingly inexorable march south. Towards Australia. Troops and equipment rushed back from Europe and the Middle East to defend our shores.

The Japanese dropped bombs on Darwin. They sent midget submarines to attack Sydney and Newcastle. German raiders laid mines off the shores of various Australian beaches, including in South Australia’s Gulf St Vincent and Investigator Strait. A washed-up mine killed two naval able seamen at Beachport in the state’s southeast.

For four years, Australians were on edge. More than a million Australians – one in seven – wore a uniform, and half of those served overseas.

Soldiers lived in constant fear for their lives and those at home endured rationing and restrictions which made today’s COVID-19 regulations appear almost liberal.

So on August 15, 1945, hours after Jones and his crew had possibly dropped the last bombs of the war, the nation paused to reflect on the magnitude of the Japanese surrender.

Euphoric celebrations erupted in the major cities as August 15 and 16 were declared public holidays. The response among the soldiers themselves was often more restrained.

Dr Karl James, head of military history at the Australian War Memorial, is reflective when asked about the emotions of the men and women on the front line when hostilities drew to a close.

“There’s a little bit of apprehension for some of them, because the question now, is ‘what next?’” he says. “If you’re a 22-year-old infantryman in Bougainville, you’ve grown up with the war. You’ve left school, you’ve joined the army and your fighting for the army.

“You’re fed, you’re clothed and you know exactly what you’re doing. Sure, the conditions aren’t great but there’s a sense of you know what you are going to be doing. ‘Now what? I’m demobilised. I’m unemployed. What am I going to do once I get discharged?’

“So there’s a real disparity of experiences – there’s no one single sense of euphoria. In the frontline areas, there’s relief, apprehension, and (a feeling of) ‘well, now what?’.”

Further from the front line, in bases such as Torokina in Bougainville, Lae in New Guinea or Morotai in the Dutch East Indies, the celebrations are more overt and, back on home soil, people party in the streets.

By 1945, any real threat of Japan invading Australia was long gone but until the US dropped nuclear bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9 respectively, most Australians expected hostilities to continue at least until 1946. When those bombs accelerated the Japanese demise, Australia was still committed to seven separate campaigns in the Pacific: Bougainville, New Guinea, Rabaul, the Philippines and three operations in Borneo.

The Japanese surrender sparked a series of ceremonies, large and small, across the Pacific and Southeast Asia, which usually involved the local Japanese commander handing over his sword and signing an instrument of surrender document.

One such ceremony occurred at Wewak, on the New Guinea north coast, only a short flight from Tadji, where Flight Lieutenant Jones and the rest of the Royal Australian Air Force’s 100 Squadron were based. Jones – whose brother Bill was a flying instructor killed in a mid-air collision above Wagga Wagga earlier in the war – had the task of flying a Beaufort bomber and its crew to the ceremony on September 13.

“When we landed at Wewak we saw a crowd of Diggers surrounding a jeep, and in the back was General Adachi, Commander of the Japanese troops in New Guinea,” Jones later wrote. “The car was being driven by a private. The surrounding crowd were taking photos and just looking. The private yelled out, ‘Take your time, fellas. I’ll keep him here ’til you’re finished’.”

Adachi and his fellow officers were forced to walk down an aisle lined with Australian soldiers.

“As the Japs walked down the strip, the troops on either side gave them plenty of stick,” Jones wrote.

“When they arrived at the surrender table, they took off their swords and laid them on the table. A Digger was heard to say ‘Struth, there’d be a thousand quid worth of swords there’.”

Once hostilities were over, Jones and his crew spent a few weeks dropping leaflets over remote areas of New Guinea, letting both locals and any outlying Japanese soldiers know the war was over. The Japanese mostly complied, though two, one in the Philippines and one Indonesia, famously refused to be repatriated and did not surrender until 1974.

About a month after the Wewak ceremony, Jones flew his Beaufort, number 603 of 700 ever built, to Wagga Wagga, where it was decommissioned.

He was discharged in January 1946 and returned to the family farm, at Cummins on the Eyre Peninsula, to resume a life which had been on hold since he and four schoolmates had marched in to an air force enlistment centre on North Terrace in September 1940. They were 18 years old and had signed up without telling their parents.

Jones was 98 when he died in Port Lincoln this year. In the intervening years he raised five children and earned a reputation as a humble, hardworking family man who was a regular at Anzac Day ceremonies on the Eyre Peninsula, especially in Port Lincoln.

Like most returned veterans, he did not open up about his war experiences until late in life, but his recollections now sit proudly on the Adelaide-based Virtual War Memorial Australia website.

The strategic and cultural legacy of World War II, in particular the war in the Pacific, in Australia was longstanding and significant.

We strengthened our military ties with the US and assumed a more sophisticated, assertive relationship with Britain.

We threw open our doors to migrants, initially mostly from Britain but eventually from other European nations such as Italy, Greece, Turkey, Germany, the Netherlands and Yugoslavia.

Australian science and manufacturing sectors exploded, cashing in on the technological advances made during the war. And many historians credit the independence of women working in factories during the war as the trigger for second-wave feminism.

Dr Karl James says events of World War II reshaped Australia in a way it had not experienced previously or since. He is sometimes frustrated by the focus of commemoration on events of World War I.

“At the end of that conflict (World War I), we have a sense of the Australian self, a manufactured notion of Anzac and a lot of people died – but there wasn’t much of a material change to Australia,” he says.

“Whereas with the Second World War, it’s a watershed moment in our history... These were the men and women who stood to defeat both fascism and imperialist Japan.

“They shaped the Australia that we grew up in. Even in the ’80s and ’90s there’s a legacy for the Second World War. And I don’t think they’ve ever been properly acknowledged in the way that they should.”