SAWeekend cover story: Motor Neurone Disease, Anna Penhall and a plea for more government help

MND is one of the worst diagnoses anyone can have, but this SA family vowed to stay positive - and push governments to do more for all sufferers of this incurable killer

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- New multi-million warchest to fight MND

- Aussies rally around FightMND

- Is this how it ends? The Neale Daniher story

Nothing is either good or bad but thinking makes it so. If you want proof of the mind’s power, come into this old Fullarton cottage, down the hall into its soaring modern extension, and sit at the Penhall family’s dining table.

Here Scott is seated by his wife Anna in her wheelchair, his hand gently stroking a leg that two years ago carried her on ward rounds as a nurse, across the tennis court and on her regular runs. Now the 49-year-old, her blonde hair freshly straightened and nails painted candy pink, sits unable to speak, eat, or move herself. Every so often she coughs, struggling to control accumulating saliva.

But behind half-lidded eyes, her brain can see and hear all.

Anna has Motor Neurone Disease, a terminal illness in which nerves that signal the muscles fail, eventually robbing the body of its ability to walk, talk, and finally breathe while leaving the intellect, sight and hearing mostly intact. The average time between diagnosis and death is around two- and-a-half years. There is no cure for the two South Australians a month who are, on average, diagnosed.

It sounds horrific. And yet as Shakespeare’s Hamlet observed – “there is nothing either good or bad” – isn’t reality just perception? Scott and Anna, and others interviewed for this story, say they refuse to see MND as a nightmare. Their thinking will not make it so.

“We’ve always been glass-half-full people,” explains Scott, a quietly-spoken, fit-looking man who refuses to see his responsibilities as a burden. “You could get very negative about it, and say ‘why me?’ and all that stuff. But Anna hasn’t done that, and we haven’t done that as a family.

“In some ways we are fortunate, because you could walk on the street and be hit by a bus. And all these things we’ve seen with the kids – milestones – Anna wouldn’t have enjoyed any of those.”

Not everyone would, or could, see it that way. But Graham Johnson, a 63-year-old in the early stages of MND, and Eliza Duff-Tytler, 72, whose partner died from it, insist while you cannot beat the disease you can still enjoy life. But to do so, they say, requires two things – a determinedly positive attitude and better, more timely government support.

They say SA is the only state not to contribute regular funds to the organisation that helps them cope – the Motor Neurone Disease Association of SA (MNDSA) a not-for-profit body that aims to help sufferers remain in their own homes rather than hospitals or aged care facilities.

And they accuse the Federal Government of age discrimination as it denies the National Disability Insurance Scheme to MND sufferers aged over 65, resulting in inferior care which can see people die before they are properly helped.

LOVE CONQUERS ALL

It was here at the Penhall’s dinner table, normally a happy place for a family who enjoy their mealtime banter as much as food, that the first sign of Anna’s trouble emerged. One day she couldn’t jump into the conversation as she usually did.

“The kids and I noticed Anna was struggling to get her words out,” Scott says. “She’d hesitate for a bit or couldn’t find the right word... It went on for a month or two and started getting worse.”

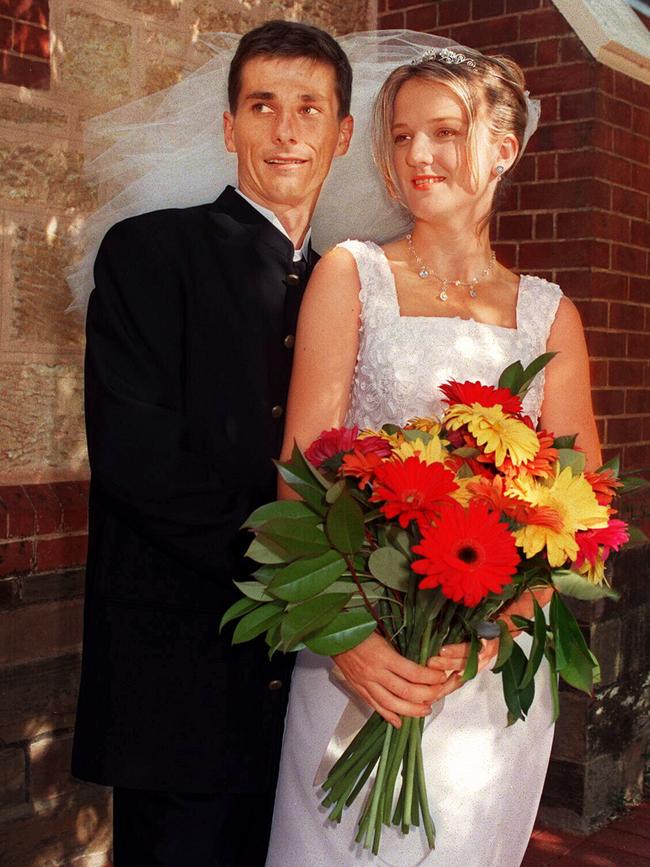

It was October 2018, and Scott realised something wasn’t quite right with his wife of 23 years, then 47, a registered nurse at St Andrew’s Hospital.

The couple had grown up in Lower Mitcham, met at university, and bonded over a love of the active life – tennis, camping, fishing. “Just her caring, friendly nature,” is how Scott describes the things that attracted him.

They’d travelled for Scott’s work as a building project manager to Malaysia, then Darwin, Brisbane and Melbourne before raising their family – Kirsty, now 20, Matthew, 18, and Mia, 12 – in Adelaide.

At first they assumed Anna had a minor speech problem, a case of being tongue-tied. Their GP and an initial brain scan found no real concern. But the tongue is a muscle – important for eating, speaking and swallowing – and complex medical tests began to point to a diagnosis that nobody would want to hear.

Much about MND, which strikes more than 700 people a year nationally, is a mystery. Its cause is unknown. There is no cure. Something causes the death of the motor neurons – the nerves which operate the muscles – and as a result the muscles weaken and stop working. It may start with the arms or legs, or the throat and the mouth, but eventually even the muscles that make us breathe will fail.

The Penhalls knew little about MND, despite having done the “ice bucket challenge” for FIGHTMND, the charity co-founded by former Essendon star Neale Daniher to raise money for research to find a cure. Daniher’s condition, diagnosed seven years ago, is relatively rare in its slow progression.

That wasn’t to be Anna’s lot. She has progressive bulbar palsy – one of four main kinds of MND – which starts in the motor nerves for speech and swallowing, and within five months of these early signs of trouble she had lost her voice. By the time she had the final diagnosis in March 2019, she was using an electronic writing board to communicate and could barely walk.

Well before then, the couple could see where Anna’s symptoms might be heading. “Obviously you start Googling, which you shouldn’t do, and type in symptoms and MND did come up,” Scott says.

They were devastated. “We spoke a fair bit then about what it all meant, and how it was really about the kids and living life still,” he says. “That was the key to us, living life. Although it was going to be harder to live life, more challenging, we wanted to live life still and let the kids enjoy their lives and not be a burden on them either.”

Since then, the family has been on holidays, celebrated birthdays and sought to keep life as normal as possible. “I think we have done that to a fair degree … the kids are also living their lives but still interacting with Anna,” he says. “They’re still bringing their friends to the house as well.”

There was another consideration: what does end of life look like for Anna? “You can do many things,” Scott says. “You can have mechanical ventilation to prolong life, but we didn’t want that. We agreed to non-invasive ventilation, so Anna might have a machine which is external and helps breathing but doesn’t go down into your lungs and breathes for you.”

In such a time, it would be tempting to think only of yourselves. The Penhalls haven’t done that. Scott paid for a video of Anna’s journey to help raise money – $25,000 so far – for the support group MNDSA, and the Laurel palliative care hospice at Flinders Medical Centre.

It is unflinching in its depiction of Anna’s deterioration, and yet uplifting as it shows the love of her children and Scott, now a full-time carer – showering her, feeding and medicating her through her PEG stomach tube, and taking her out in her electric wheelchair for daily excursions.

None of this fazes him. This is what love means. “It’s hard, but it’s far harder for Anna,” he says. “So I put it down as easy for me. I enjoy looking after Anna; she’d do the same for me. I don’t see it as a burden at all. If I can help Anna enjoy life as much as possible, that’s what I’m here to do.”

He hasn’t been able to work much since the diagnosis, but is managing with the help of family and friends, and Anna’s superannuation. He’s able to share the load with carer Jess who works five days a week, funded by the NDIS.

But, Scott says, what has also really helped is the support from MNDSA’s handful of workers who have advised on dealing with the condition and helped organise access to the array of expensive equipment such as lifting hoists, wheelchairs, breathing and suction machines through the NDIS.

WE NEED YOUR HELP

The typical person to be struck by MND is in their 50s or 60s, says Dr Peter Allcroft from the MND clinic he helped set up at Flinders Medical Centre – but he’s seen some as young as 21 and others in their 90s. Oddly, they tend to be fitter people.

“If you wanted to design an illness that could take you out, but on its way cause a lot of hardship and distress, it’s the ultimate,” he says.

The incidence is rising but it is still not common, he adds, pointing to estimates that each day in Australia two people will be diagnosed with MND, and two will die from it.

The cause is unknown, with theories ranging from exposure to toxic chemicals and blue-green algae, to genetic links and even the activation of an ancient virus in the cells. So far, there’s no cure. That means treatment is about making people as comfortable as possible during the often rapid progression. The trouble is, not everyone gets equal access to treatment.

“The big issue is the haves, and have-nots,” Allcroft says. “If you’re under 65 the NDIS does a great job and we’ve finally got special access pathways because they realise this disease changes so quickly.

“But if you are 65 and one day you are in My Aged Care … and while you might be approved for a Level Four package, which means you need a lot of care, you might die waiting for it. It deserves a class action to say, ‘this is discrimination’.”

About two-thirds of sufferers are over 65, he says. “We have people (under the NDIS) who live at home by themselves with MND and they get 30 hours of care a week; the best you can get with My Aged Care is a morning and afternoon visit, five to seven days a week. You might get 10 hours a week if you are lucky.”

Fortunately, MND sufferers can get help negotiating the NDIS or aged care system, understand how the disease will progress, and get access to the specialised equipment that can make their lives better, from local not-for-profit group MNDSA, which helps close to 200 South Australians a year.

Karen Percival, the organisation’s chief executive, says when newly-diagnosed people ask what happens next, they’re often told by doctors – “‘There’s nothing we can do for you, call these people’. And it’s our phone number”.

But Percival says the organisation is struggling, adding it is the only state MND organisation that doesn’t received funding assistance from the State Government.

With the COVID-enforced postponement of main fundraising events like Walk to D’Feet MND, now scheduled for October, and its gala dinner, it’s facing a possible shortfall of $250,000. At the same time, though, the organisation has secured NDIS accreditation, allowing it to charge for helping those under 65 to access the disability insurance scheme’s timely and helpful assistance for people with MND. That has brought in vital cash.

The State Government does provide two rooms free of rent (the deal ends next June), and did give a one-off $50,000 grant for equipment – but it doesn’t assist with wages for the seven full-time and two part-time staff.

“What we’re looking for from the government is some relief, so we are not having to frantically fundraise all the time,” Percival says. “Were fighting to be there to make sure someone is there to take the call. People want counselling, support, they have questions, they want help. And if we’re not there, there’s no one in SA to do that.”

GETTING ON WITH LIFE

Graham Johnson is a fitness fanatic who likes his statistics. The day we meet is the 260th time in a row he’s taken his morning walk since his MND diagnosis. What started at 7.4km is now 9.5km, he says.

That’s impressive, although before the disease struck the 63-year-old had run 13.1km through the streets around his Munno Para home for 951 days in a row – right until the day he went into hospital for scans in August last year.

The tests were needed to determine what was wrong with the former national manager at gas reading company Service Stream. Six years ago, he’d had some heart issues which resulted in several falls, one of which damaged his hearing so badly he needed a cochlear implant. Then, in 2019, he had some odd muscle tremors.

“I was standing in the bathroom last April and I noticed some streaks across my shoulders, flashes across my skin,” he recalls.

He went to see a neurologist at the Lyell McEwin Hospital who thought it might be related to a heart pacemaker inserted after his falls. But the hospital’s senior cardiologist had a different view, telling Johnson: “I think you’ve got motor neurone disease”. Three months of tests confirmed that suspicion.

“Unfortunately, I’ve got a fairly aggressive MND,” Johnson says as we sit in his neat brick house which neighbours his daughter’s home on one side and his father-in-law on the other. Another daughter lives five minutes away.

It was a shock for his wife Barbara and the tight-knit family, and the changes have come quickly. He’s lost 14kg, and the muscles in his arms and legs are weakening. He has annoying muscular tremors, and it’s hard to unscrew caps from bottles. He can no longer swallow his favourite treat – fresh bread with peanut butter.

While his speech seems good, he doesn’t expect that to last and is using a computer system provided through MNDSA to record 300 sentences so that if, as expected, his voice fails, he can communicate in his own words.

In the meantime, the keen footy supporter is getting on with life, watching his West Coast Eagles and, locally, Sturt. He’s also staying positive. While COVID-19 has prevented the family taking some of his bucket-list holidays, the lockdown has also meant he has spent lots of time with them.

“They’re devastated,” he says. “Probably the hardest thing for me is I’ve got a grandson, Hunter, who has just turned 17 months, so I’m making sure I see him every day. We have a very strong bond and my wife’s a bit jealous.”

He is philosophical. “Look, at the end of the day we are all born to pass away,” he says. “I can’t control it, so I’ve just got to live life to the fullest, that’s my attitude. Stay positive. I don’t let things worry me too much. I try to keep myself mentality active.”

One way he’s doing that is to raise money for MNDSA, both on his own Facebook page (so far $14,000) and by campaigning for the Marshall Government to kick in regular funding. Johnson managed to secure a meeting with Health Minister Stephen Wade, who “was positive and said he’d definitely look into it”. He also wrote to Scott Morrison, who replied expressing his sorrow at his “awful” diagnosis and with a promise to pass on the concerns to Steven Marshall.

But Morrison did not mention any changes on the broader issue of the discriminatory treatment of over-65s who are denied the NDIS. “Generally speaking, most MND patients pass away before they get the aged care funding,” Johnson says. “So MNDSA are the ones who look after them. Stephen Wade was surprised. He said he wasn’t aware of that.”

RED TAPE FRUSTRATION

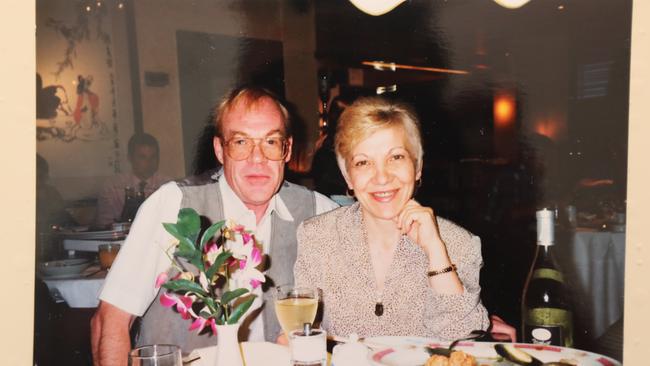

It was also a surprise to Eliza Duff-Tytler, a feisty former nurse whose partner Nick Bowman died, aged 72, from MND last year. She came to see that leaving over-65s with the disease to the aged care sector meant they were treated as second-class citizens.

Duff-Tytler, 72, first noticed a problem with Bowman in 2015.

“There was a bit of a jerk or movement in his leg, and I used to say, ‘Are you all right?’ and he’d say, ‘Of course, why are you asking me such a question?’.”

Eventually, she convinced him to seek a referral from a neurologist and when one of his sons fell ill in England, Bowman took it with him. It was there, after tests in 2016, that he was diagnosed. “He went to pieces,” recalls Duff-Tytler. “He was shocked, and if you get such a shock and fear sets in there’s no way you can have logic or reasoning.”

Fortunately, Duff-Tytler was a strong, pragmatic person. “I thank God I don’t get anxious,” she says. “I look at everything as a situation and how to overcome it.”

Once Bowman was back in Australia, he’d tell her, “I don’t know what we are going to do now; I don’t know when I will die”. But she would insist they not look too far ahead. “I would say, ‘We won’t worry about when you will die, we are OK now. And we can live our life. And we will just tackle every day as it comes and not think any further. That’s how we have to deal with this’.”

He took her advice, and they managed – but not without help. Eventually Bowman needed a wheelchair for outings around their Medindie home. It would have cost around $16,000, Duff-Tytler says, but they received the free use of one from MNDSA.

Bowman was more fortunate than some in the way the disease progressed. He lost strength in his limbs, especially the arms, but was able to mostly feed himself, and move around the house. He didn’t lose his voice. But he needed help showering.

He had to apply for help through the aged care service, but first needed an assessment. That proved impossible until MNDSA helped fill in forms.

Even tough-minded Duff-Tytler, who had been a director of nursing in aged care services, found herself frustrated by the lack of action. “Then someone rang,” she recalls, “and she was saying on the phone: we will look into it. And I said, ‘I don’t want to be rude, but I am sick and tired of hearing from various departments, “We will see to it”. What do you people expect to see? Do you expect to see that he is dead before you come and do anything about it?’

“After our talk I was rung two hours later to say they are coming to speak to me. They came, assessed, and approved to have the shower (help) seven days a week. And the approval for that shower happened one month before he died.”

Bowman lost use of his arms, which was enormously debilitating, but retained many abilities to the end. Most MND sufferers do not.

And, as Adelaide singer-songwriter Tom West powerfully detailed in SAWeekend recently, it is immensely distressing for them and their families. It’s also hard to know what their wishes might be when they can no longer easily communicate.

Allcroft recalls one man, Terry, a few years ago who was on a breathing machine 24 hours a day. “What keeps you going?” he asked. “And he said, ‘Well, I love seeing the sun rise in the morning. I love to listen to the birdsong in the morning, seeing my garden. I love my music’. And he was looking forward to a movie on television at the weekend.” But when someone is being artificially kept alive, with breathing assistance, with feeding, there may come a time when they want all that to stop. In Terry’s case his wishes were communicated slowly with the use of an alphabet board.

“I went out to his home with his family present and used medication so he would be comfortable, and we took the breathing machine off and he died very quickly after that. He decided: I’ve had enough.”

KEEPING POSITIVE

At the Penhall house, Scott has done some renovations – turned an office into a larger ensuite, widened doorways, knocked out a chimney, all to make things easier for Anna to be moved about.

She went to the Flinders Medical Centre for a check-up recently. He says the doctors were amazed at how well she was doing.

“They shake their heads and say it’s remarkable how tough she’s been,” he says, stroking the shiny strands of her blonde hair. “So whatever we can do to assist Anna – because she wants to be here as long as she can – we will keep doing it.”

He has learned a lot about MND in this journey, but what has he learned about himself and Anna?

“I think we always knew we were resilient people,” he says. “We’ve become more resilient. We’ve always been positive; we’ve had to become more positive. We’re not religious people but we have always believed if you do the right thing, ultimately good things happen to you. And we still think that, though this is not a good thing. We still believe there’s an afterlife … we believe we’re good people, so good things will happen to us when we’re not here.”

To donate, go to mndsa.org.au or Anna Penhall’s mycause page

or Graham Johnson’s mycause page