SAWeekend cover story: Inside the divisive feud over timber plantations on Kangaroo Island

The owners of Kangaroo Island’s contentious timber plantations are in a race against time to harvest and then replant after bushfires damaged about 95 per cent of their crop. But locals want the forests gone.

- Kangaroo Island: Six months from the fires

- Temporary homes give fire fire victims new hope

- Trail of terror: How the blaze took hold

- An Island Divided: The $35m plan splitting KI

Timber plantations. Mention those two words to nearly anyone on Kangaroo Island and you’ll spark either a tirade or an eye-roll.

The tirade will involve how the forests are generally a waste of good farm land and were one of the main reasons last summer’s bushfires were so ferocious and damaging. The eye-roll is a non-verbal way of saying: “Oh dear. That hoary old chestnut. Do we really want to go there?”

The concept of forestry on Kangaroo Island goes back more than half a century. Decades of unfulfilled promises have left some locals sceptical about the value of the island’s 17,500ha of blue gum and pine forests. Throw last summer’s tragic fires into the mix, when 95 per cent of trees in the plantations were damaged, and you have an industry which has become a whipping boy for angry residents looking for answers.

Keith Lamb and Shauna Black are the public faces of Kangaroo Island Plantation Timbers, the company which owns 86 per cent of forestry on the island – about 15,000ha.

Despite the backlash, they are determined to push ahead and harvest their blackened crop, determined to replace the harvested timber with more trees and refute any suggestion the forests played a major role in January’s bushfire devastation.

“Firstly, the plantations are just 7 per cent of the burnt area,” Black says. We are speaking in the company’s Smith Bay House, which overlooks the bay of the same name where a proposed multimillion-dollar deep sea wharf would help transport the logs off the island – but more on that later.

“We also have numerous examples where the plantations actually provided protection to various assets. People have told me that personally – people who are from out there (the fire-hit properties in western KI), including farmers.

“This community has a negative perception of plantations – for very good reasons. They were dudded by the managed investment schemes. All of these plantations were planted and they (the Kangaroo Island people) have never seen anything come from them.

“And so we fully understand people’s antipathy towards forestry because of that historical perspective. But no other community in Australia has that attitude towards forestry.”

Black, a former journalist and long-time Kangaroo Island resident, is the company’s executive director of community engagement. Lamb, who lives in Adelaide, is the company’s managing director, and has more than 30 years’ experience in the timber industry.

He’s been forced to draw on every bit of that experience to expedite a plan to harvest 4.5 million tonnes of timber, which is now 95 per cent fire-affected, and then somehow get that wood off the island.

The amount of land given over to timber production on the western end of KI started taking off in the late 1990s, after a federal and state government push sparked a flood of new plantations across Australia. The push, which included generous tax incentives, occurred around the same time as wool prices plummeted, and many farmers on soldier settlement blocks on KI took the opportunity to sell up to managed investment scheme companies, such as Great Southern, looking for forest-friendly land.

But the bottom started falling out of the managed investment scheme sector after the global financial crisis of 2008. Great Southern collapsed in 2009, and administrators sold its KI assets to Gunns, which also went broke a few years later. New Forests became the new owners of the majority of plantations on the island, before selling to Kangaroo Island Plantation Timbers (KIPT) in 2016.

Through all this, the trees have kept growing. But they have never been harvested. Before the fire, the KIPT plan was for this first harvest to occur over 12 or 13 years, and to replant gradually as the trees are felled. Now, Lamb says, they aim to get the wood off the island within five years, hopefully before it becomes unusable.

The company is debt free after banking $70 million worth of insurance cheques – but its share price dropped from more than $2 to just above 80 cents after the fires hit.

Lamb says the board is committed to replanting once the existing trees are removed, to make the business an ongoing concern.

KIPT valued the estate about $115 million before the blaze. The company has written down that value to about $6 million of unaffected crop but believes much of the burnt wood can be salvaged, and some can even be still sold for top dollar, because many trees remain alive up to a certain height.

Six months after the blaze ripped through the island, much of the burnt plantations now show signs of plentiful regrowth – sprouting fresh greenery from the bottom up until it meets the dead part of the tree. So the forests are now a mosaic of different damage levels. Some trees are completely dead, some have regrowth up a few metres, others are sprouting all the way to the top. Where there’s regrowth, there’s moisture, which means the wood can be sold at a standard price. But any wood above the regrowth is not taking in any moisture, and hence will gradually deteriorate.

Which is why after most fires, plantations are salvaged as soon as possible – days or weeks after the front has passed. Conventional wisdom states plantations have about 12 months to fell and sell fire-affected wood before it degrades.

But there is no harvesting infrastructure on Kangaroo Island. There is also the not-so-insignificant task of transporting the wood to potential customers on all corners of the planet.

And that’s where the wharf comes in.

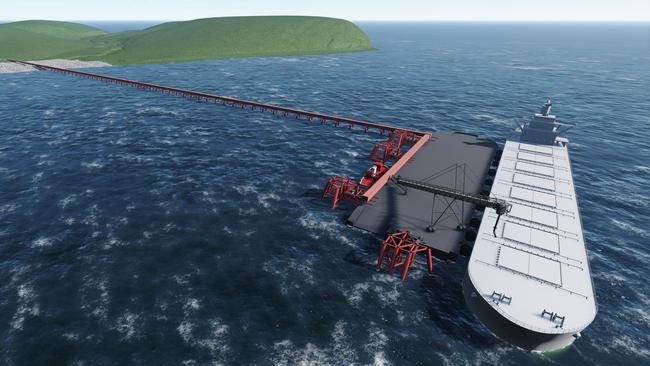

The company has lodged an application to build a $40-million deep sea port at Smith Bay and is nervously awaiting an approval announcement, expected within weeks, from Planning Minister Stephan Knoll. Lamb says loading the Penneshaw-Cape Jervis ferry with truckloads of logs is economically and practically unviable. If the port is knocked back, the company’s second-choice option is to use barges to take the logs to large ships waiting in deeper water.

A port would take nearly two years to build. Once up and running, the process of removing all 4.5 million tonnes of wood using a port would likely take another three to four years.

The wharf proposal has faced fierce opposition from some islanders, including the local council and Yumbah Aquaculture, which owns a neighbouring abalone farm. But if there is no wharf, and KIPT is forced to rely on barges, Lamb estimates it could take up to 20 years to remove all the logs.

“We don’t have 20 years to wait,” Lamb says. “Because the wood won’t last that long,” adds Black.

Lamb picks up the argument: “So the scenario is for us, if the government was to reject the port application… then the next best option for us is to start pushing the trees over and just burning them.

“And then 4.5 million tonnes of wood would turn into 4.5 million tonnes of smoke. And it would all end up over Adelaide, and McLaren Vale, and Victor Harbor – you can only imagine what the reaction would be to that.

“So that’s not our preferred strategy. Our preferred strategy is to have an orderly harvest to get the timber off, to then get back into business.”

The duo says burning the trees is also a poor option for the Kangaroo Island community, which would miss out on the economic benefit – which they put at $850m before the fires – of harvesting such a quantity of wood. The island would also miss out on a new asset – the deep-sea port.

But the burning strategy is one which many on the island would applaud. They say the forests sit on land which would be better used for more traditional agriculture such as pasture and cropping.

Agriculture Kangaroo Island chairman Rick Morris, who farms on the western end of the island, is unequivocal when asked about the impact the plantations have had over the past few decades.

“It’s created a bit of an economic wasteland,” he says. “We’ve seen virtually no economic activity out here, families have gone and the plantations are just sitting there harbouring wild pigs and are basically just a nuisance – no jobs, no people.

“We’d like to see them develop back into farmland – particularly now, given the livestock industry is so profitable. We think that the 35 original soldier-settler farms (now given over to forestry) would support 17 families plus workers and be turning over $15 million annually, which filters back through the local economy.”

Morris lost 90 per cent of his property at Karatta, west of Vivonne Bay, during the fires but his home and sheds were saved. A bit further west, Ben Davis was not so lucky.

Davis and his family were caught in their home when the January 3 firestorm ripped through, and captured the event on a video which went viral and became one of the most terrifying reminders of the firestorm’s ferocity.

For the past six months, he has spent most of his working life living out of a temporary accommodation pod while gradually rebuilding the property, about 100km away from his young family in Kingscote. He lost his home, his sheds, his sheep and his farm machinery, but says the blaze came with one silver lining.

Over the past few years, Davis had knocked over hundreds of large blue gums on a 160ha section of land his family had previously leased to Great Southern. He says the trees sucked up every bit of available water, drying up creeks and swamps, and he wanted to use the land for more traditional agriculture.

“I was knocking it (the forest) over because I couldn’t see a future in it,” he says. “And most of the trees were on the ground, pushed up in rows when the fire went through, and it did a hell of a job of cleaning them up. That’s about the only thing that was good about the fire.”

With the wood gone, and after one of the best starts to the farming season in years, a healthy crop of oats is now rising from the 160ha where the blue gums once stood.

His property remains surrounded by forest, either national park or plantations, and he swears in the affirmative when asked if he believes the blue gums played a role in the size of the fire. And he says once the island’s current crop of trees is either harvested or burnt, the land would be better used for crops, sheep and cattle.

“I just can’t see it (forestry) being a viable option,” he says.

Mayor Michael Pengilly is equally blunt.

“I can tell you straight out the community just wants the trees gone and the land returned to primary production,” he says. “The history of forestry on the island has been a decades-long disaster. And they were an incendiary device during the fires. They played a huge part in the intensity and the size, there’s no question about that.”

Lamb believes the mayor is wrong. He says the timber industry has a proven history of fire management strategies and is adamant the forests contributed to the inferno, which started in Flinders Chase National Park days earlier, no more than any other form of land use. He maintains the fires could, and should, have been contained within the park before the cataclysmic conditions of January 3. But they were not, and that day will forever be etched in the memories of locals. The fire destroyed or damaged 119 houses, burnt 211,474 hectares, killed nearly 60,000 livestock and, tragically, claimed two lives – Dick and Clayton Lang.

“What we’re seeing is a small group of people who are using the fire as a reason to have a go at us when they’re not standing back and looking at the bigger picture,” Lamb says.

“All we’re asking for is to be considered as part of the bigger picture and not be used as a scapegoat, because our losses are as great as anybody else’s on an individual basis.”

Lamb says January’s devastation should force a rethink of the fire management strategies within the national park and wilderness declaration areas.

“Climate change may exacerbate fire risk, reinforcing the need to modify native vegetation management policies and emphasise direct attack strategies to avoid a repeat of the 2019-20 Kangaroo Island fires,” he wrote in KIPT submissions to both the state and federal inquiries into this summer’s bushfires.

The animosity on Kangaroo Island towards forestry is widespread, but not universal. And across Australia, the industry has injected invaluable economic stimulus to many rural regions, including in South Australia’s South-East. Mount Gambier Mayor Lynette Martin says forestry employs more than 3000 people, either directly or indirectly, in her region – which includes the state’s largest regional city. “I would certainly not like to see the industry disappear from our landscape,” Martin says. “It’s the lifeblood of our region.”

It’s a similar story across the nation. Australian National University researcher Dr Jacki Schirmer says, unsurprisingly, the creation of local jobs is a key factor in a community’s acceptance, or otherwise, of forestry. Schirmer has produced a PhD about the social conflict surrounding the establishment of new timber plantations.

“What you tend to see is this big period after establishment, but before the first harvest, where there’s not a lot of employment, and that’s often where there’s the biggest concern,” she says.

“Concerns are related to things like fire risk, and are there enough people on the ground and are there local jobs? This improves in a range of ways once there have been more jobs.

“People don’t necessarily love them (the forests) but you tend to see people saying: ‘I may not love them but they do contribute to jobs locally and I can see them as part of the community now’.

“Once they get established for a long time and they are proven to generate jobs locally – that’s if they generate jobs locally, and not all plantations will, but, if they do – that certainly leads to more community acceptance of them.”

Schirmer says land used for established timber plantations generally produces the same amount of jobs, albeit in different locations, as land used for cropping and pasture. But plantations can never compete with labour-intensive industries like dairy farming on a jobs-per-hectare comparison.

The jobs are yet to flow from the millions of trees, most of them now burnt, on Kangaroo Island. KIPT employs about 11 people on the island and another half a dozen on the mainland.

But the company’s economic modelling predicts an ongoing forestry industry would create 160 direct and more than 70 indirect jobs on KI. Modelling also predicts a sustainable $50m annual boost to the island’s economy.

With that in mind, Keith Lamb and Shauna Black are pushing on. They have categorised their burnt forest into high, medium and low-risk of degradation, and aim to harvest and export the high-risk crop first with a goal to still selling it as fresh wood, which is used in products as diverse as furniture, nappies, fabrics and textiles.

They plan to use a sprinkler system at a dam west of Parndana to keep any dead timber moist but even if the logs dry out they could sell as fuel wood, to a different market at a reduced price.

So they want to harvest and export the wood as quickly as possible, hence the need for a deep-sea wharf, and plan to replant once this crop is removed.

The concentration of timber plantations near the national park is another concern of Lamb’s, who believes moving future crops further east would mitigate the fire risk. He has also raised the prospect of three-year growth cycles – current rotations are anywhere between 10 and 30 years, depending on the type of tree – to reduce both the biomass available to burn, and the potential economic blow if a fire came through.

The fact he is even discussing future rotations won’t be music to the ears of some locals, but Lamb and Black are unapologetic.

“Forestry will provide the third pillar for this community and its economy,” Black says. “We (here on the island) have agriculture and we have tourism – both are subject to the vagaries of international markets and things like COVID-19. We can add forestry as a third bow to the Kangaroo Island economy and create a better diversity for the island.

“And forestry is a green industry – it stores carbon. It’s a fantastic industry and something that Kangaroo Island should be associated with. We understand there are some historic issues, but we want to start fresh. We want to be an active and contributing part of this economy and the agricultural community, and we think we can all work together.”