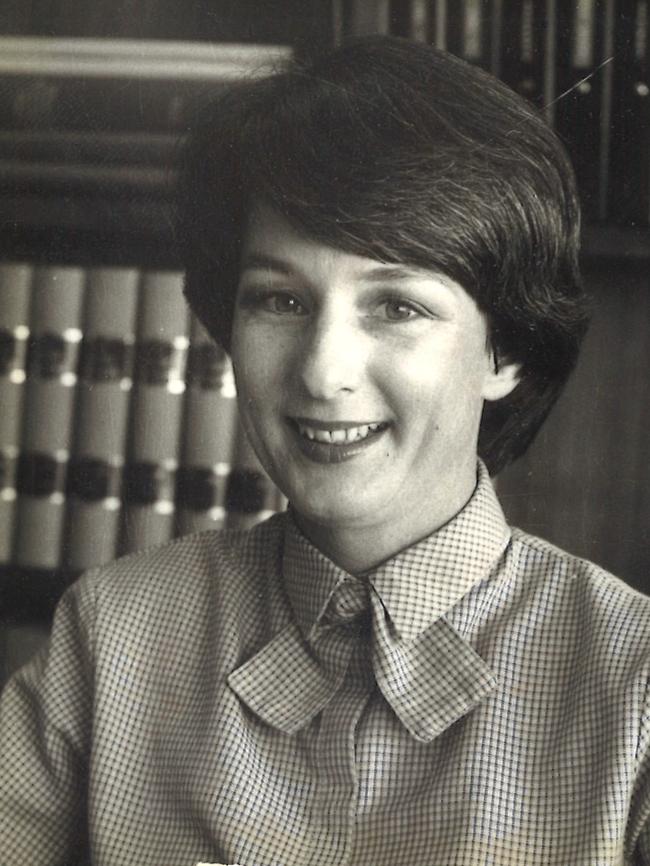

SAWeekend Cover Story: Adelaide Uni’s new chancellor Cathy Branson on her career, sexism and why we all need respect

Recently appointed Adelaide University chancellor Cathy Branson opens up on sexism, a pioneering career, her new role and why everyone has the right to feel respected in the workplace.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Making Adelaide a global education hub

- The SA women who changed history

- Why Adelaide’s three unis should become two

- Readers can reap rewards

Ask Cathy Branson what makes her cross and the former judge is quick to give her verdict: people being deliberately disrespectful to others and treating them unkindly.

For example, says the new Chancellor of the University of Adelaide, she gets angry when she sees managers make unreasonable demands on their junior staff or fail to show them compassion.

Then there are those who disrespect women with sexist judgments about what they should, or shouldn’t, be doing. Imagine someone had questioned why she had allowed herself to be considered for the position of Chancellor, since “that’s really a job for a senior man”.

“That sort of thing,” she says, suddenly steely, “would be inclined to make me angry.”

Understandably. Branson, 72, has had a stellar career. She is an AC (Companion of the Order of Australia), Queen’s Counsel, the first woman to be a Crown Solicitor, a former Federal Court judge and an ex-president of the Australian Human Rights Commission.

But it is telling that, even though nobody has suggested a man would have been a better choice, it flits across her mind. It is the sort of thing she has become used to as a woman – people making “stereotypical judgments about me to my face”.

“Aren’t you lucky to have a husband who will buy you such a nice car,” a stranger told Branson recently. And even in legally sensitive matters, she often finds people automatically deal with her husband, a retired medical specialist, instead of her.

“The notion that a man, in preference to a woman, should take the lead on matters of legal or business significance is proving hard to eradicate,” she says dryly.

Now, though, Branson has another chance to break that mindset – and champion the cause of respect – as Chancellor and chair of the university council, the board which sets the strategy for the nation’s third oldest university, in one of its most desperate hours.

There is a gaping hole in Adelaide’s billion-dollar annual budget largely thanks to the loss of fees from foreign students unable to attend because of COVID-19 restrictions. In response, the university wants its almost 4000 staff to accept plans for tough cost-cutting that will still mean 200 job losses.

Added to that is uncertainty from the mysterious resignations of Adelaide’s two most senior leaders: Vice-Chancellor Peter Rathjen and previous chancellor and former governor, Rear Admiral Kevin Scarce.

Rathjen announced last month he was quitting due to ill health, while Scarce left without explanation in May.

The council now needs to find a new vice-chancellor urgently, and Branson, who was Scarce’s deputy and has been on the council since 2013, acknowledges the challenges. “I’m not a university historian,” she says, “but I’d be surprised if the university has faced a more critical time.”

Not that Branson seems weighed down by it as we meet in her spacious office. She’s relaxed – “call me Cathy” – and proves to be comfortable discussing her life, and forthright about the struggles of women in the workplace, if circumspect on some university issues.

But Branson makes clear Adelaide’s challenges can’t be solved by money alone. While the council’s main task is keeping the university financially secure, the welfare of staff and students must have high priority, too. In her first message as chancellor she called for a “renewed and refreshed” culture of concern for individuals.

“This is something I feel deeply about; everyone has the right to feel respected in their workplace,” she says. “And I have learnt through personal experiences that people perform at their best where they feel welcome.”

Branson is only Adelaide’s second female chancellor, after Dame Roma Mitchell, who had the position from 1983-90. Dame Roma – also a QC, judge, and federal Human Rights Commission leader – was a role model and mentor for Branson. Does a woman bring something different?

“I think there is a style from spending your life as a woman, and a style that comes from having spent your life as a man,” she says. “I’ve sought to do some jobs that only men have done before, but I haven’t tried to look like them in doing it. I have tried to bring my own style and my own personality to what I do. So, yes, I hope I do look different to the men.”

EARLY DAYS

Branson grew up in the bush, on a traditional wheat sheep property in the Mid North, where her no-nonsense father made her learn to drive every vehicle, including tractors. Her playmates tended to be boys. “I mainly did what boys did,” she says. “I didn’t play with dolls. I think I just took for granted pretty early that the things boys could do, I could do.”

She was not a diligent student, she admits, during her time at what is now Seymour College.

Branson had few specific ambitions but thinks her father’s dream would have been for her to have married “a wealthy pastoralist who would come and buy large numbers of merino rams from him”.

In 1966, when university beckoned, Branson planned to study psychology. Instead, she was allocated to the new Flinders University, to study geography and Spanish. The only place for psychology was Adelaide, where she could study the discipline if she took law or economics. Since her brother was already doing economics, Branson chose law.

“At the end of the year I was one of a very small number of students to pass all my subjects at the first attempt,” she says. “I thought, ‘gosh, maybe this is something I can do’.”

Her success excited her parents, who thought that would make her a great legal secretary – once she learned to type. But Branson, stirred by a new wave of feminism, thought it would be odd if she worked for men who were less talented in law than she was.

Then, on an extended trip to the US in her early 20s, newly married to her first husband, John Branson, she had another formative insight, this time on social justice. While her lawyer husband worked, she volunteered at a legal aid office near Michigan. “That was a serious eye-opener for me,” she says. “I had never been exposed to that level of disadvantage in my life: the triple disadvantage of being African American, being poor and being trapped because they couldn’t get out of violent relationships. That was a very influential period.

“It made me understand how much disadvantage is structural. It’s so easy to believe that those living underprivileged lives somehow should be carrying some of the blame for it.”

Later as a lawyer and judge it influenced her thinking, especially about the power of the state and the rights of the citizen

That thinking echoes still in her message about respect. “My notion that every individual is entitled to be treated with respect and to be given the opportunity to make the most that they can with the life that they have, is all based around that I think,” Branson says.

CEILING SMASHER

When she returned to Australia, still unsure she wanted to be a lawyer, Branson did her articles of clerkship in a local law firm where, in the early 1970s, women accepted that the law was a man’s place and “it was not for us to come in and start making too many complaints about it”.

Sexual harassment was common, she says, and she suffered some “modest” examples. “At the time, I can recall reacting in ways that I still read sometimes of young women reacting (today), that is completely freezing over, saying nothing, doing nothing, just standing like a statue until it was over,” she says.

“Or if it was just something like putting their hand on your knee … just slowly edging away out of reach but not complaining. We were expected to feel that male attention was somehow flattering but you couldn’t complain without ruining your possibility of continuing to work … so your choice was to put up with it, or if it got serious enough, you left.”

Don’t the findings about former High Court judge Dyson Heydon’s sexual harassment of young female lawyers at the court and elsewhere suggest the problem remains, decades later?

Branson says she was shocked at the allegations and the news that some of the best and brightest young women in the profession had left as a result of the alleged harassment at the nation’s highest court. She has joined calls from women lawyers to make the profession safer for women with a new independent complaints body and a transparent judicial appointments process.

“It shows we must think more deeply how to handle it,” she says. “I think we have to accept that hierarchical places are places where very poor conduct can be tolerated, that you wouldn’t expect to be tolerated. The protection we place around really senior people in hierarchies – the judiciary and the legal profession … universities have their strong hierarchies as well – we’ve got to be alert to the danger that comes from that.”

Adelaide is not exempt. “There are almost certainly pockets of this university where the culture is not what we want,” Branson says. That could deter talented people wanting to work there. It gets back to respect, she says: “No one harasses a person that they truly respect”.

It wasn’t harassment that saw Branson leave private practice, but a broader sense of discrimination. For example, the firm wouldn’t let her do industrial workplace injury claims because she might hear swearing on a factory floor. “They didn’t turn their mind to the fact I had had a childhood around shearing sheds, and I had a fairly well-developed vocabulary of my own.”

She felt a job in government, which in the 1970s under Don Dunstan was pushing social change and equality for women, might be better. Branson applied to be a research officer with Solicitor-General Brian Cox, who represented SA in court, and got the job. She impressed Cox and soon found herself helping him in High Court hearings. Opportunities opened up. “Where you feel welcome,” says, echoing her message to the university, “you also end up doing your best work.”

Next, Branson worked at the Crown Solicitor’s office, giving legal advice to the state government and accompanying Dunstan once to a premiers’ conference as his legal adviser. After a few years, Branson, who says she enjoys change, decided she wanted to work in private practice as a barrister.

But Attorney-General Chris Sumner wanted her to stay, and that resulted in an offer in 1984 to be the first woman in Australia – and possibly anywhere – to be Crown Solicitor and head of the Attorney-General’s department.

Branson, then just 35, spent sleepless nights wondering whether to take it. She knew it would outrage many of the men in the office. “Eventually he (Sumner) needed courage, I needed courage, and we agreed to give it a go,” she recalls.

Ultimately it went well, she says. Some older men left, creating more opportunities for younger people. “After two years we had the most vibrant, best performing government law office in Australia,” she says.

Branson eventually did make her move to the private bar, and she tells an instructive story about how women can change a work environment simply by being there.

She applied to join Bar Chambers, which had no women, but did have a lively and very blokey atmosphere that included boozy sessions after hours, dirty jokes and barristers sleeping in their offices. There was some reluctance at first to include a woman, but soon they found the place was much more pleasant for her presence. “They found the changes that came with it, they liked,” Branson says.

ROLE MODEL

In 1994, just two years after being made Queen’s Counsel, she was appointed to the Federal Court bench. “I think it was positive discrimination,” she says of that decision. “I don’t believe I was appointed Crown Solicitor because I was a woman. I think most people thought I was.” But she does think she was offered the Federal Court position as early as she was because of her gender.

“There was serious and legitimate concern that the courts would lose the respect of the community if they could not increase diversity among the judiciary,” Branson says. “I think being one of a few women who were doing advocacy work in our superior courts did mean people saw me and knew about me.”

The move to increase women on the bench made “a great change”. “It stopped the judiciary from being gentleman’s clubs, really … But it also gives them the opportunity to explore ideas with female colleagues,” Branson says. “You know, ‘I had a female witness today. She said this. What do you reckon? Could that be an experience that women would have?’

“This discussion among judges is healthy and good. So the influence of the few women was quite disproportionate to their number.”

Branson spent 14 years on the bench, most of them in Sydney, and was mentioned in legal circles as a possibility for the High Court but nothing eventuated. Then in 2008 she was offered the role of President of the Australian Human Rights Commission, a job that took her out of the cloistered life of the judiciary.

It was stressful at times. The plight of the homeless, unemployed and families of children with disabilities were part of her job, as was visiting confronting places like Australia’s mandatory detention centres.

“You only had to look at them to see the distress, the mental harm being done to them,” Branson says of those held there. “These were hard, hard days, the days I spent in immigration detention facilities … but an experience that every person holding any form of senior office in Australia should have, just to understand what’s really involved in our policy of mandatory detention.”

The centres were the opposite of Branson’s concept of respect and decency, and the job in general a culture shock. Like her time in the US, it gave her an understanding of the world she’d never have otherwise had.

Now, she’s determined to use her new position to embody respect. “I do feel that the personal values and personal conduct of the chancellor is very important in setting a tone for behaviour,” Branson says.

Role models matter, she points out. It was one of hers, Dame Roma, who quietly urged Sumner to offer her the Crown Solicitor position so many years ago. “It’s commonly said, it’s hard to aspire to something you haven’t seen,” Branson says.

Another key issue on which she intends to set the tone is academic freedom and free speech, with some universities accused of stifling debate that could offend China because of their dependence on Chinese students for income.

BIG CHALLENGE

Branson rejects that approach. Universities need “the strongest culture of respect for academic freedoms, and free speech”, she says – but insists the presence of the Chinese Government-funded Confucius Institute on campus does not compromise that.

The biggest task, though, is to keep Adelaide financially sound. The reason it is struggling, like many universities, is that it has built its budget on the fees of foreign students – and COVID-19 has put a big hole in that boat. Those fees helped pay for expensive research programs that all the universities say are vital to Australia, but which governments refuse to sufficiently fund.

Now the question is: Where will the money for research come from? Especially when Federal Education Minister Dan Tehan wants to cut Commonwealth cash for domestic student course fees, putting even more pressure on university budgets.

Tehan’s plan to sway students to take what Canberra thinks will be more job-oriented degrees has come under intense criticism for being unfair, inconsistent and trying to pick winners. Branson sounds unimpressed. “We are disappointed to see that humanities and social sciences students face a more than doubling of their fees – to a level significantly higher per year than, say, medical students will incur,” she says. “We are also surprised to see a proposed overall funding reduction to universities for engineering, science and agriculture enrolments – the very areas the government is seeking to prioritise.”

With a budget crisis, health crisis, troublesome new federal government plans, and no vice-chancellor (Professor Mike Brooks is acting in the role) Branson and the university have their work cut out.

She seems to be looking forward to the challenge. After a lifetime of breaking down gender barriers, here is another opportunity to show women’s capabilities – and at any age. After all, there’s Ita Buttrose chairing the ABC at 78, and Branson’s close friend and former Federal Court colleague Margaret Stone, in her mid-70s, the current Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security.

“It would be nice to think that it might be a sign that ageism for women is on the retreat,” Branson says.

Yet she makes clear barriers for women remain. When asked whether in the 1970s it had been difficult for a young woman to be ambitious, she says “it still is”.

“People don’t like ambition in women in the way they like it in men,” Branson explains. Ambition can be a loaded term, an implied criticism that a woman is “aggressive” or not sufficiently “feminine”.

“This double standard, with its stereotypical assumptions about appropriate female behaviour, can be damaging to women. I think women who want to make careers for themselves need to have the sense of what they want to make of themselves in their lives, but they have to manage public perceptions of that in a way men don’t have to do … women just have to manage themselves differently if they are going to hold the public esteem.”

For young women setting out, she offers this advice: Be courageous – but not foolhardy. Remember that your male colleagues are likely to over-estimate their abilities, so don’t underestimate yours. If you seek professional success, choose a life partner who is also ambitious for you. Develop a logical career plan – but at the same time retain the flexibility to run with an unexpected opportunity if it seems right for you.

And there is probably another suggestion, although it applies to everyone: show respect.

“I think there’s never any need to actually treat people knowingly unkindly,” Branson says.

“You can manage performance, you can speak about poor behaviour, without descending to the cruel and the unkind.”