SA Weekend: South Australia’s First Nations warriors equals on the battlefield but not at home

During WWII Corporal Timothy Hughes was accepted as an equal by his white cobbers but once in civvies he was an outcast. In 2022, little has changed for SA’s First Nations warriors.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

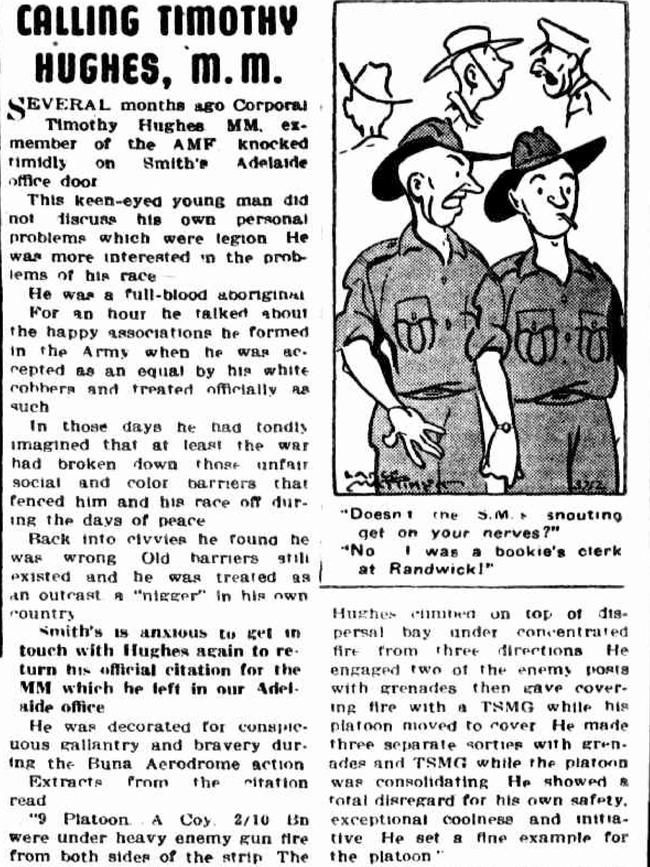

It was your average winter’s day in 1947 when Corporal Timothy Hughes knocked timidly on the office door of one of Australia’s most popular tabloid newspapers.

Hughes, a decorated Aboriginal soldier from Point Pearce on the Yorke Peninsula, had served for almost six years during World War II, returning home as one of the nation’s most decorated soldiers.

But despite his achievements, which included saving his platoon single-handedly from heavy gun fire, the “keen-eyed young man” did not plan to discuss his own personal problems that day. Indeed, two years after being discharged from the army, Hughes was ready to go into battle once more – this time for his own race.

“He was a full-blood Aboriginal,” Smith’s Weekly reported on August 2.

“For an hour he talked about the happy associations he formed in the army when he was accepted as an equal by his white cobbers and treated officially as such.

“In those days he had fondly imagined that at least the war had broken down those unfair social and colour barriers that fenced him and his race off during the days of peace.

“Back into civvies, he found he was wrong. Old barriers still existed and he was treated as an outcast ... in his own country. This man can’t even lodge a vote!”

While the newspaper article did little to change the mindset of the Australian government at the time, it did accurately reflect a tale of two worlds – one of inequality and racism, the other of mateship and patriotism.

A tale which dates back to the Boer War in 1899, which is the first recorded overseas action where First Nations people served alongside white Australians.

While the total number of participating indigenous soldiers remains unclear, nine troopers and a private, as well as a tracker and a scout, have so far been identified.

More than 1000 Aboriginal men and women also served in WWI, and at least a further 3000 during WWII.

Hundreds also served during the Malayan Emergency and Indonesian Confrontation, the Korean War and, more recently, the Vietnam War, East Timor, Afghanistan and Iraq.

It is estimated about 5000 indigenous people have contributed to warlike services over the past 123 years, including 450 known soldiers from SA.

However, with additional research and more First Nations people finding out about their ancestors’ service and making their identity known – that number continues to grow.

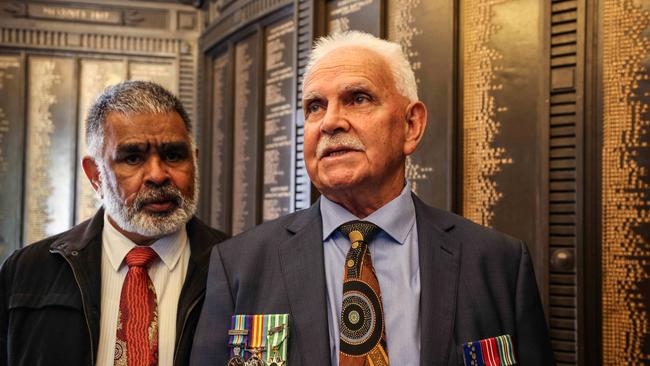

It’s also allowed for the identification of unmarked graves due to the work of groups such as Aboriginal Veterans SA, which has been working tirelessly to record and remember indigenous servicemen and women since 2015.

“Some of the difficulties with researching Aboriginal services is being able to identify people as being Aboriginal from records,” AVSA co-chair Ian Smith says.

“So we often have to rely on families to identify relatives who have served.

“When you add the early deaths of many Aboriginal people, due to ill health and other things, there are not a lot of Veterans around to share their stories and fill the (knowledge) gap.”

Smith, who has written a book, For Love of Country, about Aboriginal Veterans from SA, says military service has held a special appeal for Aboriginal people for well over a century.

This, he says, was due to indigenous people being economically disadvantaged through colonialism and its ongoing legacies, particularly during WWI and WWII.

For many, joining the army, navy or air force offered a chance to escape from the shadows of the Protection Act which, up until 1969, segregated them from the rest of Australia.

This included their right to drink, earn a living, vote, marry, and even own a dog.

They also were restricted to government reserves and missions, and were unable to own land.

In 1940, government authorities also introduced rules that tightened entry to the armed forces, subsequently preventing “Australians of non-European origin or descent” from joining the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Imperial Force.

Some recruitment officers ignored the rule and some Aboriginal men also claimed other racial identities, such as Maori, Pacific Islander or even Jewish, to get around restrictions.

During WWII, Aboriginal men were also sought after as a cheap labour force by the Australian government.

“(Government representatives) turned up at missions in 1942 to get the young men onto the trucks and conscripted them to do labour work in the Northern Territory,” Smith says.

“When the war was over and they returned home, they found that their missions were cut in half with parcels of land given to white soldiers ... only a few Aboriginals received land themselves, but that number was marginal.

“It was sad because many enlisted to create a better life for themselves, but that was often not the case.”

Wartime tales of survival inspire

The treatment of Aboriginal veterans has had a profound impact on Ngarrindjeri ex-serviceman Frank Lampard OAM.

Mr Lampard, who completed national service in 1966 and served in the army medical corps, says his childhood was marked with stories of his brave and courageous Uncles, including Private Arthur Walker, Private Frances Alban Varcoe, Private Cyril Spurgeon Rigney, his brother Private Rufus Gordon Rigney, and Private Walter Gollan, who all died on the battlefield during WWI.

But the story that shaped his childhood most was that of Uncle Roland Wenzel Carter, who was married to his biological aunt, Vera.

Born February 28, 1892 at Goolwa, Carter enlisted as a private in the AIF in 1915 – making him the first Ngarrindjeri man to enlist.

He served with the 50th Battalion and on April 2, 1917 participated in an assault on Noreuil, a French village fortified by the Germans.

After receiving a serious gunshot wound to his left shoulder, he was one of 80 men captured by the Germans.

After his injuries were treated at an army hospital in France, Carter was moved to a Prisoner of War camp in Wünsdorf, Germany.

The camp was providing German anthropologists with the opportunity to interrogate and study POWs from diverse backgrounds. Prisoners were photographed, their portraits painted, and their voices recorded.

“Not a lot of people know that Aboriginals were kept as Prisoners of War where they were studied,” Lampard says.

“But it’s an interesting part of history. When I was a kid and we went back to the mission, we used to go around to Uncle Roland’s place to see him.

“He’d sit there, surrounded by all of these photographs of different places and him in uniform and, of course, back then, we never thought of getting called-up and enlisted ourselves.”

Lampard says while he was too young to share in his uncle’s wartime stories – Carter died in 1960 – his memory has lived on via stories.

It includes his unique friendship with Leonhard Adam, one of the anthropologists who had observed Carter as a POW in Germany.

In 1929 Adam published an article based on information gained from Carter and Ngadjon/Ngadjan man Douglas Grant from Queensland, entitled “On Customs and Law of Some Australian Tribes. A Personal First-Hand Account from Two Aboriginals”.

Following the introduction of anti-Semitic laws in Germany in the 1930s, Adams fled to England from where he was sent to Australia in 1940.

“He became a professor at Monash University and, one way or another, they got in contact with each other and became friends,” Lampard says.

“They became so close that when (Adam) got sick and couldn’t travel anymore, he was getting close to his death, he insisted that his daughter go over to South Australia to visit Roland and bring him up to date with what was happening.

“It’s an incredible story of friendship, considering everything.”

Equality in the ranks

Two years after Carter’s death, Australia committed almost 60,000 personnel to the Vietnam War efforts, including ground troops, naval forces and air assets.

In 1964, an amended National Service Scheme was introduced by the Menzies government through a national ballot for men aged 18.

First Nations people were once again exempt from service.

This, however, did not stop an estimated 300 men from enlisting, including 15 known Indigneous men from SA.

Among them was 21-year-old Leslie Kropinyeri from Tailem Bend who, since the age of 15, had been working as a porter for the railways in Murray Bridge.

Eager to escape the dusty railyards, Kropinyeri registered for national service on the hunt for adventure.

In January 1967, his number finally came up and he received his call-up papers and a request to attend a medical.

“I was standing in line in my socks and jocks along with the 19 other blokes having the medical at the same time,” he recalls.

“I was the only Aboriginal there and the doctor said, ‘Do you want to go any further?’ and I just looked at him and said ‘What do you mean?’.

“He said, ‘Oh, you’re Aboriginal and I can exempt you and you can get dressed and go home’. But I told him that marble doesn’t differentiate and that I would keep going.”

Fit and healthy to fight, Kropinyeri became part of the second intake of National Servicemen on April 20, 1967, completing his basic training at Puckapunyal.

Only three months later, he was transferred to Singleton for corps training, where he was chosen as one of only 20 men to complete the Regimental Duties Instructor’s course.

He was subsequently promoted to Corporal.

“They saw something in me, a bit of leadership quality,” he says.

In November 1968, Kropinyeri was on board HMAS Sydney en route to Vietnam.

He says he didn’t experience any race discrimination, which was much in contrast with the segregation he witnessed among US soldiers.

“I got along with everyone and they got along with me,” he recalls.

“I was fairly lucky that I got the experience and that I got out of it. Lucky that I came back alive ... and it gave me discipline and life skills I didn’t have before.”

For Port Augusta local Francis “Frank” Howard Clarke, Vietnam drew parallels with his experience of growing up in the bush near Bordertown.

Clarke joined the Australian Army in 1964 at the age of 17, due to his dislike of school and with the encouragement of his uncle, who was already in the army.

“I didn’t do very well and hated school,” he recalls.

“I didn’t want to do what my father did and that was shearing sheep. So I thought joining the army would be a bit of an adventure.”

Ranked as a private recruit upon entry, Clarke completed his basic training after three months at Kapooka, NSW, before he was posted to the infantry centre at Ingleburn.

After another three months of training, he joined the 2nd Royal Australian Regiment but was eventually moved to 5RAR, with whom he eventually deployed to Vietnam on May 11, 1966.

During his time overseas, Clarke says he participated in every enemy contact his platoon engaged in – six in total.

It resulted in his platoon emerging with the highest number of kills in the battalion during his 12 months in Vietnam.

Clarke’s platoon also helped “clean up” after the well-known Battle of Long Tan where 18 Australians were killed on August 18, 1966.

“We were put on 10-minute standby to go out to the battlefield and help them out, they couldn’t get helicopters or armoured personnel carriers for us so we were on standby all through the night,” he says.

“The next morning, after Long Tan, we went out early in an armoured personnel carrier and had to swim across a flooded river with us battered down inside (the vehicle).

“When we reached the bank we headed towards the 6th Battalion to help with the search of the battlefield.

“There, I met up with my brother-in-law in the afternoon ... but that’s all I remember from that day. Once we left the battlefield, everything after that is a blank.”

While Vietnam left Clarke with post-traumatic stress disorder, he says he would do it all over – if only to continue his family’s proud military service.

“I was very glad I had joined the army because my grandfather was in the First World War,” he says.

“My two uncles, Reg and Tom, were in the Second World War, and Tom was in Korea and Malaya as well. So I thought I might as well join the army too.”

A new dawn

Today, the ADF has a full-time force of about 58,600 personnel – of which 3.5 per cent are Aboriginal.

While this equates to just over 2000 Aboriginal men and women, this number has increased in recent years as part of a military-wide push to recruit more members from diverse backgrounds – and this number could grow even further.

In March this year, Scott Morrison and Defence Minister Peter Dutton unveiled plans to boost the number of ADF personnel to almost 80,000 by 2040, amid strategic risks posed by China and Russia.

Under the $38bn plan, the military would reach its largest size since the Vietnam War.

While the plan hinges on the federal election in May, SA’s support of Aboriginal Veterans is unwavering.

In 2019, Flight Lieutenant Steven Warrior was appointed the state’s first indigenous Liaison Officer to be based at RAAF base Edinburgh to help strengthen the ADF’s relationship with indigenous communities across the state.

“I play a reasonably big part in assisting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander members that are local here in Adelaide,” he says.

“Being a defence member, there’s a requirement to move around and for a lot of Aboriginal people it means moving away from our spiritual homeland and where we come from.

“We also run cultural awareness initiatives ... as Aboriginal culture is part of Australia’s history and it’s important to understand how they were treated during that first contact period, what they experienced during WWI and WWI, right up to now.”

Plans are also underway to host what is believed to be Australia’s first Aboriginal-led Anzac Day Dawn Service at the National War Memorial in Adelaide on April 25.

Warrior, who will be conducting a smoking ceremony on the day, says he encourages South Australians to join Aboriginal Veterans at the Dawn Service.

“It’s important that we recognise the service of all Aboriginals, but especially those that served at a time when they weren’t even classed as citizens in a country they ended up sacrificing their lives for,” he says.

FIVE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN WAR HEROES

They were persecuted and stolen from their families. But when the time came to fight for Australia, thousands of Aboriginal men and women were willing and ready to put their lives on the line. At least 450 South Australian Aboriginal Veterans are known to have served and died in conflicts around the world since the early 1900s. Here are five of these heroes who deserveour recognition.

Private Andrew James Enoch Rankine, WWI

Born on December 19, 1898, at Raukkan, Andrew Rankine enlisted on July 21, 1917, in Adelaide and embarked on the ship Aeneasthree months later. He served as a private with the 27th Battalion but was transferred to the 48th in April 1918 as theirnumbers had been seriously depleted.

On May 3, Rankine took part in the attack on Monument Wood, near Villers-Bretonneux. At 2am, after a short and inadequateartillery barrage, he and his fellow soldiers moved into No Man’s Land.

As they advanced they were met by heavy machine-gunfire. As dawn broke, a truce was arranged so the wounded could be recovered and the dead buried.

The 48th Battalion lost 155 men and nine Australians were taken prisoner, including Rankine. He remained a prisoner of waruntil the end of hostilities.

He returned to Australia on the Ulysses in January 1919.

Private Gordon Charles Naley, WWI

Gordon Naley was born at Mundrabilla Station on January 20, 1884. He was working as a labourer when he enlisted in the AustralianImperial Force on September 17, 1914, less than seven weeks after the outbreak of war.

Posted to the 16th Battalion, Naley took part in the landing at Anzac Cove on April 25, 1915, and the fierce fighting on Pope’s Hill and at Quinn’s Post in the following month.

In late May he was evacuated with enteric fever and could not rejoin hisunit in France until August 1916.

Naley fought in the Battle of Mouquet Farm a few days after rejoining the 16th Battalion, and in the First Battle of Bullecourtin April 1917, where he was wounded and taken prisoner.

He was repatriated to England in January 1919. Two weeks later he married Cecilia Karsh and the couple shipped back to Adelaide.

Naley died at Myrtle Bank in 1928 aged 44.

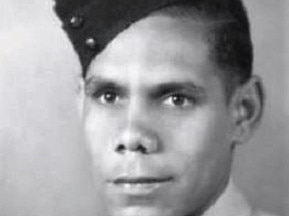

Corporal Timothy Hughes MBE MM, WWII

Tim Hughes was a Narangga Kaurna Aboriginal man from Point Pearce in the Yorke Peninsula.

He enlisted in 1939 and posted to the 2/10th Infantry Battalion.

Hughes took part in the defence of Tobruk, Libya in 1941, and fought the Battle of Milne Bay, Papua, during August to September1942. In December, his unit joined allied forces assaulting Buna.

On December 26 his platoon was pinned down by gun fire.

Hughes climbed on top of a dispersal bay and threw grenades at twoJapanese posts. Using a sub-machine gun, he then protected his fellow soldiers while they took cover. He made three sortiesto silence the enemy’s weapons, enabling the platoon to consolidate its position. For these actions he was awarded the MilitaryMedal.

He returned to Australia in 1943 and was promoted to Substantive Corporal, joining the 31st Employment Company.

Leading Aircraftman George Tongerie, WWII

George Tongerie was born about 1925 and grew up at the Colebrook Home in Oodnadatta, known for raising children of the StolenGeneration.

At age 17, Tongerie decided to join the air force. After seeking permission from the Protector of Aborigines, he travelledto Adelaide where he enlisted on June 29, 1943.

He served from 1943 until 1946 as a flight mechanic with 86 Squadron RAAFin Borneo and New Guinea.

The squadron flew air interception and ground attack missions against the Japanese. Tongerie recalled later: “It was not muchfun when your mates went out on a raid and you had no idea who would return.”

He was discharged in 1946 and recalled being treated unfairly.

“When Maude (wife) and I moved into our war service home ... people living in the suburb raised a petition to get us out.”

Marjorie Anne Tripp, WRANS

Marjorie Anne Tripp is believed to be the first Aboriginal woman to enlist into the Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service.

She was born in Adelaide and, in 1963, was looking for a career. She recalls that she had to decide on either becoming an air hostess or join the service. Following the example of her cousin and brother, she decided to join the navy.

After basictraining at HMAS Cerberus in Victoria, Tripp was posted to HMAS Albatross in Nowra, NSW, where she served for two years.

In those days marriage, for women, meant obligatory separation from the service and Tripp ended her career in 1965.

She later worked as a manager in the area of Aboriginal Affairs and was awarded the Centenary Medal in 2001 and the Premier’sAward for service to the Aboriginal community in 2010. Source: Aboriginal Veterans SA, Virtual War Memorial.