SA Weekend: New Supreme Court Justice Sandi McDonald’s long road to the top of her profession

Sandi McDonald has had a front-row seat to many of SA’s worst crimes over the past generation. Now she faces a new challenge as one of our top judges. Nigel Hunt has the inside story.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The grey, windswept shores of Dundee in Scotland are a world away from the calm, almost serene confines of the Supreme Court in Victoria Square.

But that’s where South Australia’s newest Supreme Court Justice Sandi McDonald’s long and adventurous journey to the pinnacle of the legal profession began 47 years ago.

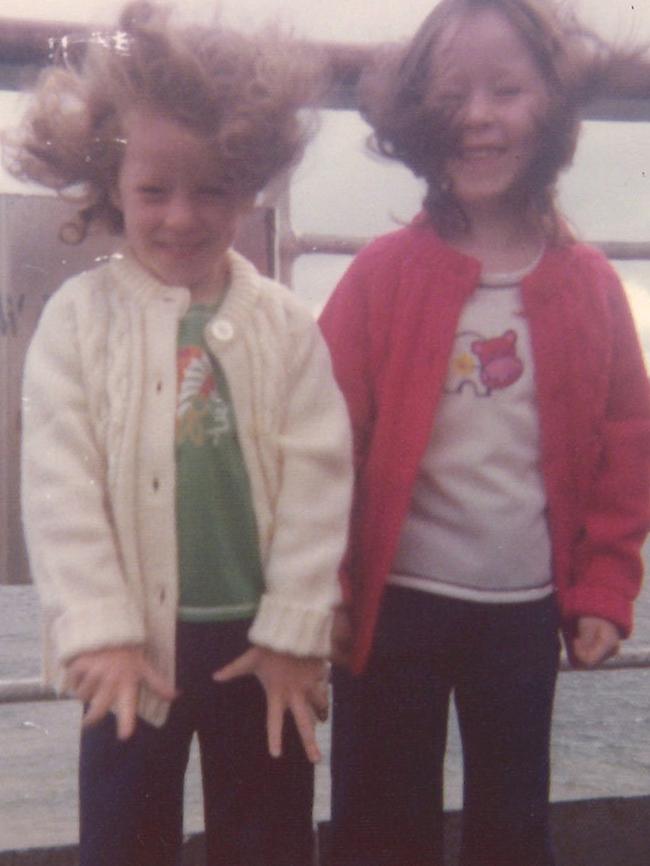

Clutching the deck railing of the steamer Australis as it cast off from the dock at Dundee bound for Adelaide in 1975, the diminutive five-year old obviously had no inkling she was destined to become a key player in South Australia’s justice system many years later.

Joining the Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions while still completing her law degree, McDonald would emerge as its most senior and longest serving prosecutor and over almost three decades would prosecute hundreds and hundreds of serious cases – dozens of them involving SA’s highest profile criminals.

The cases are literally the who’s who of South Australia’s killers including child killer Dieter Pfennig; the Snowtown serial killers; and wife killer Zialloh Abrahimzadeh. Other notable cases include notorious Salvation Army serial child sex offender William Ellis; the bikie war trial of Aaron Cluse, a Hells Angels prospect who shot the son of a rival Finks gang member during a botched attack; and a number of landmark cases involving historic rapes in which the offenders were convicted decades later using DNA evidence.

Most have spent a good proportion of their lives in prison – or are still behind bars – because of McDonald’s tenacity and meticulous presentation of the evidence against them gathered by investigating detectives.

It’s fair to say McDonald’s appointment to the Supreme Court surprised the career prosecutor. She hopes to be a role model for other women from similarly modest backgrounds who aspire to be leaders, not just in the legal profession, but in their chosen fields at the same time as raising children.

Like thousands of other migrants who sailed to Australia in the 1960s and ’70s, McDonald’s parents, Eddie and Sandra, were seeking a better life when they left Scotland with daughters Sandi and Lisa, a year junior.

Eddie McDonald was the eldest of 10 children. The family was poor, his father was wheelchair-bound, suffering from multiple sclerosis. An electrician in Scotland, he gained employment with ETSA when he arrived in Adelaide before working as an electrician for Wormald. He died 18 years ago.

Sandra McDonald is now 73. A nurse, she continued in her profession after arriving in Adelaide and, now retired, lives not far from her elder daughter.

Celebrating her sixth birthday on the ship while en route to Adelaide, Justice McDonald can still remember some events from the journey – such as the on-board shenanigans associated with crossing the equator, tasting her first mandarin and a birthday treat consisting of a Mars bar, a packet of chips and a Coke – and then living at the crowded Pennington migrant hostel before her parents built a house at Para Hills West.

She went to Pennington primary school for a short period, then Para Hills primary school where a teacher encouraged her mother to enrol her at St Monica’s parish school at Walkerville. While in grade 7, McDonald won a full scholarship to Wilderness School.

“In primary school I was the perfect student, I did well and was well behaved,’’ McDonald recalls. However, she readily admits she went off the rails in year 9 and 10 and turned into a rebellious teenager, discovering nightclubs and boys.

“I went through that stage, but pulled it all back together and finished high school. My grades were good, but not what I should have got,’’ she says. “I was too distracted by everything else that was going on, but good enough to get into law school.’’

After finishing school and turning 18, McDonald took a gap year and travelled through Europe, backpacking the continent with a female school friend and staying with family in the UK.

Surprisingly, McDonald’s initial choice for a career wasn’t law. She had enrolled in a business degree at the University of Adelaide before departing overseas. Abroad she realised she had made the wrong career choice and switched degrees – her decision influenced by the fact she had been involved in debating at high school. She both enjoyed it and was good at it.

“It seemed a natural segue from that. I was strong at humanities, I was a good debater and communicator,’’ she says.

“But I really didn’t know what I was getting into because none of my family had been to university. My sister and I were the first two. I didn’t know anyone who had worked in the law, so I was really quite ignorant.’’

She had no “light bulb’’ moment which switched on a long-term career focus within law. It wasn’t until she was more than halfway through her degree that she realised where her career was heading. That was when she did criminal law, topping that year and winning an award.

Nearing the end of her studies and discovering her friends were all applying for clerkships with commercial law firms, McDonald had no intention of treading that path. But fearing she may miss the bus employment-wise, McDonald penned a letter to then attorney-general Chris Sumner looking for a job. Her letter made its way to then crown solicitor Alan Moss and finally landed with then director of public prosecutions Paul Rofe QC.

“Out of nowhere I got a phone call from Paul Rofe. He told me he had received the letter, with me expressing a wish to become a summer clerk, but he explained his office didn’t actually have them, but he said he would like to meet me,’’ she says.

“I went in and met him and he said ‘I would like to give you a job here’.’’

McDonald jumped at the chance, joining the office in 1992 while completing her diploma of legal practice. She worked closely with Rachel Doyle, the daughter of then solicitor-general and later chief justice John Doyle. Almost two decades later Rachel Doyle’s skill in eviscerating Victorian police commissioner Christine Nixon during the bushfire royal commission would become the stuff of legal legend.

“I went in for the summer and never left,’’ McDonald says.

She can still remember the first jury trial she ever prosecuted, not long after she was hired by Rofe. It was also the first one she lost.

Nervous and slightly terrified, the fledgling prosecutor’s trepidation was heightened by the fact her debut would be overseen by Justice Margaret Nyland, whose reputation demanded respect from senior prosecutors and instilled fear in juniors such as McDonald.

The case involved a hotel bouncer who had been charged with assaulting a patron after overzealously ejecting him from a Hindley St premises. Little did McDonald know that while she would lose this case, the result would be somewhat different in an almost identical case in which she prosecuted a bouncer charged with the manslaughter of a patron at the Ramsgate Hotel 15 years later.

“I would have been dreadful in the first trial. I was told on the eve of the trial it was going to be a Supreme Court Justice hearing it, not a District Court judge. It was Margaret Nyland who has just been made a Supreme Court Justice,” she recalls.

“I was just glad I made it through to the end, just getting there, it was terrifying.’’

Just as she can recall that first jury trial involving the hotel bouncer, McDonald has vivid memories of the Ramsgate hotel manslaughter trial in 2007. She says it was “an extraordinary case that no one ever thought would result in a guilty verdict”.

She remembers police coming to see her in the DPP office with some CCTV footage of the incident from the Ramsgate’s cameras, which showed a bouncer holding a patron in a headlock for an extended period of time and asking “do you think this is worth investigating or is it just a Coroner’s Court matter?”

“I took one look at it and said ‘it has to be prosecuted’,” she says. “It was a very difficult trial because the accused could have been anybody’s son who got caught up in the heat of the moment that night. No one ever though he would be convicted because of the nature of the case.”

McDonald recalls the sentencing proceedings, before now retired Justice Michael David, when the families of both the accused and the victim were in court.

“They were all nice people, the emotion in that courtroom was incredible because Justice David sentenced him to jail. There was cheering from several relatives and Justice David yelled at them to stop,” she says. “The emotion was so incredibly raw from both sides.”

The case was controversial because the first verdict was successfully appealed; the accused convicted of manslaughter a second time and that conviction also successfully appealed, and finally the manslaughter charge being discontinued because of doubts over securing a third conviction.

When McDonald joined the ODPP full-timein 1993 its armoury of prosecutors included the likes of Ann Vanstone, Trish Kelly, Wendy Abraham, Steve Millsteed, Barry Jennings, Peter Snopek, Adam Kimber, Martin Hinton, David Whittle and Jim Pearce.

Of that now distinguished group, only Pearce remains and with McDonald’s departure, he is now the office’s longest serving and most senior prosecutor. Pearce is about to prosecute what will be the trial of his career – the eight men accused of the murder of Jason De Ieso, an innocent victim in a bikie feud. The other prosecutors went on to become legal luminaries in several jurisdictions including the Supreme and District Courts, the Magistrates’ Court, the Coroner’s Court and in Abraham’s case, the Federal Court.

McDonald recalls Snopek being her first supervisor and mentor for more than a decade in her early years. Despite his stature and gruff nature that tended to intimidate many, she says he “had a heart of gold”. Abraham, whom she would many years later be junior for in the Snowtown murders trials, was another mentor.

She describes her early years in the DPP office under Rofe’s leadership as much more casual than its latter years. She also recalls the turmoil that surrounded the larger-than-life Rofe’s eventual demise as director and the severe impact it had on the staff.

“Rofe was well liked and respected. Whilst he was a flawed human being, you could not help feeling for him in that situation. It seemed to snowball,’’ she says.

After Rofe’s exit as director, the office was led by Abraham for some time until the position was filled. Overlooked for the role when outsider Stephen Pallaras was appointed, Abraham opted to leave. Perhaps being diplomatic, McDonald says she was largely insulated from the public brawls that unfolded between Pallaras and the Labor government during his tenure because of the sheer number of large trials she was involved in.

She recalls being delighted when in 2012, then deputy director Adam Kimber was appointed director. Close friends since law school – and responsible for Rofe recruiting him – McDonald says Kimber was “an excellent director and I was glad to see him appointed”.

While she was disappointed when he was not reappointed when his seven year appointment expired in 2019, she wasn’t completely surprised because none of his predecessors had been reappointed at the expiry of their terms.

When Kimber departed, McDonald ran the office for six months. She candidly confesses she threw her hat into the ring for the job – only to have second thoughts.

“Having done the job for that period of time I came to the view it wasn’t the job for me,’’ she says. “I remember reflecting on it sometime later telling myself, ‘my daughter is 14; in seven years she will be 21 and I will have missed out on an awful lot running an office of that size because you are not just the no.1 prosecutor, you are running a large organisation.

“I realised that wasn’t the best course for me. Once those years of your child’s life are gone, they are gone.’’

Having all but completed the application process – even down to having her interview before a panel of legal and government heavyweights – she had to work out how to delicately withdraw her application.

“People were pretty shocked,’’ she says.

McDonald withdrew her application on the eve of a planned overseas holiday for a month and deliberately left her mobile phone at home, telling husband Peter Salu not to tell her anything about Adelaide while they were away.

When she arrived home she had a message waiting from Attorney-General’s department chief Caroline Mealor advising her that then Supreme Court Justice Martin Hinton had been appointed as director.

“I was pleased, really pleased,’’ she says.

Save for veteran Jim Pearce, it is unlikely any other prosecutor will better McDonald’s unbroken stint of 28 years as a prosecutor. She attributes that longevity to the fact she simply loved the work and was not motivated by money or opportunity to join the bar as a barrister, as many of her colleagues did during that time.

“The challenges kept presenting themselves,’’ she says. “There is something about pulling a case together that is rewarding, joining those dots and bringing it together in a compelling way. It is hard to dissect it down to which part you enjoy the most.

“And every day you feel like you are making a difference, what you are doing matters to people and it impacts on their lives. Not a lot of people can say that about their jobs.”

While McDonald assumed many management roles within the DPP office before being appointed deputy director in 2012, she admits when a big case was under way those duties took a back seat.

And while securing a conviction in a prosecution was always satisfying on several levels, surprisingly, she says losing a case against an accused individual never troubled her deeply.

What did profoundly impact her was witnessing almost daily, people at the lowest point in their lives because of the circumstances that led them into court.

“You are seeing how crime impacts so many on both sides of the bar table. People’s lives are just destroyed, such as in a [causing] death by dangerous driving case, by just a moment of inattention,’’ she says. “There are no winners; there are victims on both sides.’’

This often manifested well before any trial ever eventuated, recalling one case in which a mother had been responsible for a car accident in which her car hit her teenage son and resulted in both of his legs being amputated.

“The director had to make a decision whether to prosecute or not. What could we do to her that was worse than what she was already going through?’’ she says. “They are the worst kinds of cases.’’

While her husband and daughter might disagree, McDonald says she does not tend to take such emotion home with her. There have never been any nightmares or cold sweats after recalling the often shocking images captured in crime scene photographs, graphic confessions or witness statements.

“You have to at some stage, there are moments, but I think I am really lucky in that I have a natural resilience that has always enabled me to shut off,” she says.

“I am naturally a very positive person and I think that is part of it, that enables you to basically turn that knob down.’’

To a large extent Salu agrees. McDonald was 26 when the pair met. A barrister, he was involved in a civil trial in Mt Gambier at the same time McDonald was there on circuit court. The pair ended up dining every night and their love blossomed. Like most couples who work in the same field, they try to avoid talking shop at home. He can only remember a handful of occasions when she has vented seriously. He also says her years of experience as a prosecutor have made her a “kinder, more compassionate person than she was 20 years ago”.

At home McDonald says she switches off by immersing herself with her family, and with weekend activities likely to revolve around her daughter’s sporting commitments. Chores associated with hectares of grapevines also demand attention. Socialising and entertaining friends also feature, as does cooking when the mood strikes. Overseas travel is a passion that has been curtailed by Covid.

McDonald readily admits she is no longer surprisedat the extent of man’s inhumanity and capacity for violence towards others. As a young prosecutor in the Snowtown murders she was exposed to enough violence and depravity to last two lifetimes. Yet despite her being continually exposed to extremes of violence and cruelty over almost three decades, it hasn’t resulted in her being hypervigilant with her own family.

“As a mother, for me seeing a parent lose a child is just the worst thing imaginable. But equally, as a mother having a child, seeing a child do something stupid and ending up going to jail is equally unimaginable,’’ she says.

While the level of violence in crimes has not changed over time, McDonald readily admits she has witnessed the law change over the past three decades. It has become more complex, legislation governing it more onerous and technology “has become a killer”.

In the vast majority of all major criminal cases ranging from homicides to drug trafficking, evidence now includes DNA, telephone intercepts and listening device material, telephone tower tracking, computer analysis and CCTV footage – often from dozens of sources.

“Body worn footage is a good example; every police officer now has a camera on them. How do you manage that, how do you manage that there may be 30 people with footage of an incident in terms of looking at it all, determining what is relevant, what is disclosable,” she says. “I think it is a big problem we are about to move into.’’

Perhaps because she has spent her entire working life in an office in which females outnumber men, McDonald says she has never experienced any sort of harassment or bullying from colleagues. Similarly, she believes she has never missed any opportunities because of her gender, but believes she has had to work harder because of being a mother.

“The problem has always been for women who have children. A lot of women do not have the flexibility I have had to go to court five days a week,’’ she says. “The fact they are automatically precluded from running trials if they can’t be there five days a week has to be a problem I think. I think the single fact that holds women back in the law is their choice to be a mother. It is their choice, but there are some consequences that go with it.’’

McDonald believes there is hope in this regard, with the pragmatism that has crept into the running of trials via video, rather than insisting all parties appear in court, over the past two years because of Covid restrictions.

McDonald had taken a month off and was enjoying the sun and sand at Palm Cove in Queensland shortly after prosecuting what would prove be her last trial – the National Crime Authority bombing – when she got the phone call on September 29 that would drastically alter her future.

It was the first day of her fortnight-long stay and she had left her mobile in the apartment when she went for a stroll along the beach. Glancing at the phone when she returned, she noticed a message from then attorney-general Vickie Chapman asking her to call her back.

After some small talk, Chapman told her: “Let me tell you what I have planned for you.”

“I told her I needed some time to speak to my husband and daughter about it, I needed some time to process this, but in all likelihood I would say yes.”

McDonald says while being given the relatively rare opportunity to sit on the Supreme Court bench had never been an expectation, the thought “was always in the back of your mind”.

“If you told me back in law school that this is where I would end up, I would have said you are kidding me.

“You don’t have to come from money, from the establishment, to succeed in this country. That is why my parents came here and look what happened to me.” ■