SA Weekend cover story: In a life campaigning for Aboriginal rights and reconciliation, Lowitja O’Donoghue, now 88, was driven by childhood grief, says her first biography

Taken from her mother, trained to be a servant, SA’s Lowitja O’Donoghue became a voice for justice. Now, a new biography by Stuart Rintoul charts her journey – and the pain that drove her.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Over the course of her life, Lowitja O’Donoghue has received many awards and honours: Commander of the Order of the British Empire, Australian of the Year, National Living Treasure, Companion of the Order of Australia, and Dame of the Order of St Gregory the Great, a papal honour, even though she is not Catholic.

In 1996, she was a contender to become Governor-General and had Australia voted to become a republic, she might have become our first president. Now 88, she is one of the nation’s great matriarchs.

Former prime minister Paul Keating, who sat opposite her to negotiate the nation’s first native title laws, called her “a remarkable Australian leader … whose unfailing instinct for enlargement marks her out as unique”. Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson, who sat alongside her, called her the greatest Aboriginal leader of the modern era, “the rock who steadied us in the storm – resolute, scolding, warm and generous, courageous, steely, gracious and fair.”

Aboriginal MP Linda Burney says of her, “If there is one woman that you would identify as being someone that inspires you, that terrifies you, that is a symbol of possibility, it would be Lowitja. The dignity, I think, is the thing that you remember the most.”

But Lowitja’s life has also been marked by great sorrow. Born in the desolate beauty of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands of South Australia’s north, she was taken from her Aboriginal mother, Lily, at the age of two, and did not see her again for more than thirty years.

By the time they were reunited her mother was a broken woman, living in great poverty. They could not speak the same language. Her white father, who handed his Aboriginal children to missionaries to raise, abandoned them and vanished completely from their lives. It left an aching void.

“I am sometimes identified as one of the ‘success stories’ of the policies of removal of Aboriginal children,” Lowitja said when she retired from public life, twelve years ago, standing in the pulpit of St Peter’s Anglican Cathedral.

“But for much of my childhood I was deeply unhappy. I felt I had been deprived of love and the ability to love in return. Like Lily, my mother, I felt totally powerless. And I think this is where the seeds of my commitment to human rights and social justice were sown.”

Three years ago, Lowitja entrusted me with writing the biography she had long resisted. We had spoken about it from time to time, but she was always too busy living. She was more than eighty years old and packing her memories into boxes before she thought it might be something worth doing and then she called me and said, “Let’s get on with it”.

The result is a book that took me from Central Australia to the Indian province of Assam, in the foothills of the Himalayas near the border of Bhutan, where she worked as a nurse among Baptist missionaries in 1962 before devoting her life to the Aboriginal cause. It is the story of the remarkable rise of an extraordinary woman – and the price she paid for rising.

I start the book in October 1979 … Lowitja O’Donoghue is standing in sandhills outside Oodnadatta, in the remote backblocks of South Australia. It is hard dry country, unforgiving, desolate. A small group of people stand huddled in the wind, staring down into a hole.

Not a hole, a grave. Her mother’s grave. Lily. The mother she barely knew. The grave has been dug, but the wind is blowing and the sand is pouring back down into it. The men are trying to dig it out, sweat soaking their shirts, the sand pouring back down. Lowitja’s head aches.

Oodnadatta is where she was brought at the age of two, when her father, a white man by the name of Tom O’Donoghue, gave her to missionaries to raise along with her sisters and brother – first two of them and then three more, brought in by camel and cart. Their mother is silent, invisible in his world. She was Anangu, a Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara woman, whose people have lived in the desert and granite ranges of Central Australia for tens of thousands of years. He was first generation Australian, Irish Catholic, a stranger who stayed for a while and then went away.

When he was gone, Oodnadatta is where Lily lived, in a scrap iron shanty on the edge of the town. It’s where they were reunited, Lily and Lowitja, mother and daughter, after more than thirty years apart. They stood mute in front of one another, not able to speak the same language, Lowitja’s mind full of questions that would never be asked because she could see the pain sweep across her mother’s face and decided there and then to cause her no more suffering.

This is not where they had intended to bury her. They’d wanted to take her north, back to her country, the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara lands where her story began; but time defeated them so they are burying her here, in the sandhills, where they will not find her again.

Lowitja stands watching the digging, sand pouring back into the grave, sweat soaking their backs. She looks at her sister, Eileen, and laughs and then they are all laughing, while the casket sits waiting to be buried. None of it makes any sense …

July 1876. A young Irishman, Timothy O’Donoghue, pushes his way along the throbbing docks of Plymouth, England, “that excellent harbour” as the writer Daniel Defoe described it. It’s loud with the sounds of cargo being loaded; men, women and children scramble to find their way; ropes strain against the tide.

O’Donoghue is 21 years old, the youngest son of a large, poor Catholic family, from Killorglin, County Kerry. It’s a place of thatched roofs and stone walls, where the River Laune ends its journey from the MacGillycuddy Reeks and the Lakes of Killarney and spills out into the harbour and the sea. He is a young man with empty pockets and big hopes.

Born in 1855, in the wake of the Great Famine, the mass-starvation and disease that killed more than one million people in Ireland and caused even more than that to emigrate, Timothy O’Donoghue has been raised around people deeply scarred by what it is to die of hunger. Few counties suffered as badly as Kerry during the famine. In just three years, from 1845 to 1848, almost a fifth of its population either perished, or fled – to America, Canada, Australia. Many took their chances in the heat and dark and stench of ships where death was so common they were called the coffin ships …

The Bencleuch sailed from Plymouth on 8 July 1876 with 443 souls on board – 326 adults, 100 children under the age of twelve and seventeen children under the age of one – and arrived in Port Adelaide on 18 September with 444 on board. Two children, both boys, were born just before arrival. Four children, two boys and two girls, were stillborn during the voyage. One child, a seven-year-old boy by the name of John Kennedy, was lost overboard.

From the deck of the Bencleuch, Timothy O’Donoghue looks out on Port Adelaide and a new life, one that he will have to build from nothing. He has just half a sovereign in his pocket and a young wife in Ireland waiting to join him …

In 1878, Timothy and Margaret O’Donoghue settle in the Hundred of Pinda, in the dry land north of Goyder’s Line, separating land fit for farming and land prone to drought. They suffer hardship and heartache and raise a family of thirteen children. Two of them, Mick and Tom, go north, into Central Australia, past the railhead at Oodnadatta, where missionaries worry and pray and sing hymns in the desert and gather up the children of white men and Aboriginal women, including seven of the children of Mick and Tom O’Donoghue.

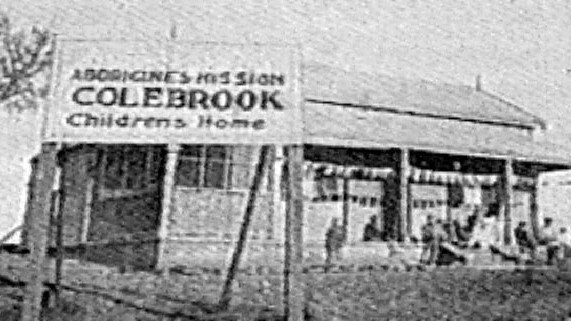

In August, 1932, somewhere near a station called De Rose Hill, Lowitja takes her first breath. Her birth is not registered. Not her name, not the day, not the place. It is just four years after the Coniston massacre, just seven hundred kilometres away. Australia is in the grip of the Great Depression. In September 1934, she is handed over to the missionaries, who have established the Colebrook Home for Half-Caste Children at Quorn in the Flinders Ranges. They call her Lois, a Biblical name, and give her a birthday, August 1, the birthday of horses.

Tom O’Donoghue stays in Central Australia until the end of 1940, when the land breaks him, as it has broken his brother and their father before them. In November 1940, he is also arrested and prosecuted under the Aborigines Act for “carnal knowledge” of Lily. He walks away. At Oodnadatta, mounted constable Cyril Keith Bradey writes to the Chief Protector of Aborigines, William Penhall, that while Lily was O’Donoghue’s “lubra” for a long time, his parting words were, “I could not marry any of the black bastards”.

O’Donoghue ends his days in Adelaide, while Lily drifts to Oodnadatta, lives with an Aboriginal stockman, Jimmy Woodforde, has his children, and falls on hard times. At the Colebrook Home for Half-Caste Children, Violet O’Donoghue runs through the house, bare feet padding on the floorboards, calling out for her little sister.

“Iti,” she calls, using the Pitjantjatjara word for baby. “Iti …”

Lowitja is “the baby”, although by now she is a child, the youngest of the O’Donoghue children at the Colebrook Home. Vi is her protector. Their bond will run deep all their lives. It will be Lowitja’s earliest memory, the loving sound of her sister running through the house calling for her, and then, as she gets older, riding on her brother Geoffrey’s back with her feet tucked into his pockets, all the two miles to school.

It is a crowded house, full of children taken from their parents and told to forget, watched over by spinster missionaries Ruby Hyde, who is short and stout with hazel eyes that see everything, and Delia Rutter, who is small and thin and gentle. The missionaries are devoted to God and to the children; but at night, when the house is quiet, a child is often crying.

Some of the children will carry that ache all their lives, while others will describe Colebrook as “a loving sanctuary” and say that they were not stolen from their mothers but saved – from violence, or abuse, or poverty. One of the children, Faith Thomas, will remember constant love and attention. Another, Nancy Barnes, will write of her time at Colebrook: “We didn’t miss out on anything as I recall. Except perhaps our mothers”.

Lowitja does not feel loved. For her, Colebrook is a place of rigid discipline and joyless religious observance, bad food and endless hymn singing and praising of the Lord. It is the ringing of the triangle that hangs near the well, and being punished for “childish things”. The sting of a strap soaked in water and allowed to dry to make it harder …

She is often in trouble: “I remember in my very earliest days standing up for what I believed in. One of the earliest memories I have is of coming between the matron and the strap. I would often stand in the way when the strap was intended for others, with the result being that I, too, got a beating.”

The children are told that Aboriginal culture is “of the devil”. They are forbidden from asking questions about their past – their parents – and they are forbidden from speaking their native languages. So, out of earshot of the missionaries, they make up their own secret “Aboriginal” words, and cling to those they remember, including the Pitjantjatjara words tjitji tjuta – many children.

When new children come into the home, they huddle around them and ask the questions that the missionaries will not answer: “Do you know my mother? Do you know where she is?” In this way, Lowitja learns that her mother’s name is Lily, that she is “a full-blood Aborigine”, and that she is living “up there … in the bush”. The children are very young. In November 1941, the secretary of the United Aborigines Mission, Reverend AB Erskine, writes to Chief Protector Penhall, saying the mission prefers children to be seven years of age or under: “Over this age it becomes increasingly difficult to control them, as they have learned so much of the bush ways and habits.”

In photographs, Lowitja is a little girl in grey second-hand clothes, wishing she had something bright and frilly to wear. She tries desperately to be noticed and spends hours brooding over how she has come to be here, without a mother and a father, and why no-one comes to get her: “When I was very tiny, I would ask, ‘Who am I, who is my mother, who is my father, where do I come from?’”

By the time she is seven or eight, she has stopped asking: “I wasn’t getting any answers. The other children in the Home became my family.”

But in the bleak records of the Chief Protector in Adelaide, a police report tells, heartbreakingly, of a mother who did search for her missing children.

Just before Christmas, 1945, an Aboriginal woman arrives in the town of Quorn with two young children at her side. She has travelled more than 500 kilometres through desert country from the remote township of William Creek.

She attracts the attention of police sergeant Bill Kitchin, who ascertains that her name is Lily and that she is making her way to the Port Augusta Mission, where she believes she will find her five children. She has no means of subsistence.

If Kitchin, a policeman for thirty-three years, knows, or suspects, that Lily’s children are at the Colebrook Home, which was at Quorn for seventeen years, from 1927 until the previous year when it relocated to Eden Hills, in the foothills of Adelaide, he does not tell her.

He provides for Lily and her children for two days while they wait for a train, buys her a ticket to Port Augusta, and sends her on her way. Then he sits down and writes to Chief Protector Penhall, advising him of what has transpired and asking to be reimbursed for his costs.

At the Aborigines Protection Board, the Chief Protector, a lifelong Methodist and occasional lay preacher, who routinely refuses to reunite half-caste children with their Aboriginal parents, acknowledges the correspondence and agrees to pay his expenses:

Dear Sir,

I have your letter of the 10th inst. reporting the arrival of Lily and two children without means of subsistence, and their subsequent transfer to Port Augusta.

I am grateful for your interest and help in this case, and will be pleased to defray all expenses if you will kindly submit a claim.

Yours faithfully,

WRP

Secretary

Aborigines Protection Board

Lily does not find her children. She goes back to Oodnadatta, where four years later, a photograph will be taken of a wurley of scrap iron on a barren flat: “Old Lily’s camp north of Oodnadatta, c1949”, the caption says.

That year, in August 1949, Lowitja is told that she is going to be a servant. She packs an old suitcase and says her goodbyes. Before she leaves, Matron Ruby Hyde tells her that she confidently expects she will soon be pregnant and will amount to nothing. She walks out the door and down the road.

“Bugger them all,” she thinks to herself. “I’ll show you.”