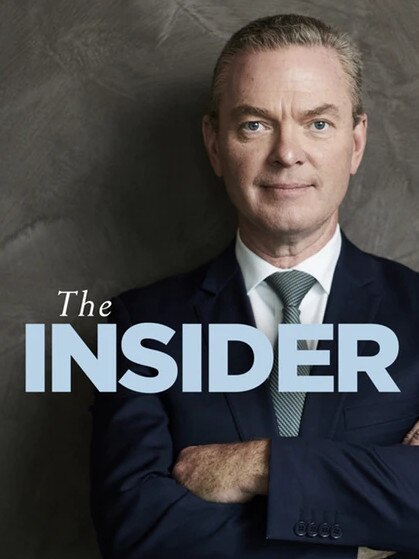

SA Weekend cover story: Christoper Pyne’s new book, The Insider, pulls back the curtain on the Canberra coup culture that crippled Australian politics

Liberal powerbroker Christopher Pyne’s new book pulls back the curtain on Canberra’s coup culture, his most formidable opponents and the big opportunity he missed to try to save Malcolm Turnbull’s political hide.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Pyne book extract - Dutton’s mistake in 2018 coup

- How the parties used pincer move to crush Xenophon in 2018

- Latest Advertiser rewards

- Read more great features in SA Weekend

In the days before Malcolm Turnbull’s political demise in August 2018, two Liberal powerbrokers who could have swung enough votes to give the Prime Minister a last-minute reprieve kept trying to talk – and kept missing each other.

The pair were friends, and an odd couple at that: Mathias Cormann, the Belgian-accented conservative leader of the Right from Perth and Adelaide’s more fruity-toned Christopher Pyne, who held sway among the party moderates backing Turnbull.

Despite big differences on policy from time to time, Pyne would regularly stay with Cormann and his family when visiting Western Australia and, as he writes in his new political memoir, The Insider, “in a world where trust is like gold dust, Cormann and I trusted each other”.

On the Wednesday of that week, two days before Turnbull was ousted, Pyne and Cormann kept trying to catch up – on the phone, via WhatsApp, with messages left with their secretaries. “I wanted to know if he had jumped ship,” writes Pyne in the book.

“Later I found out from him that he wanted to know whether I believed Turnbull’s leadership was politically salvageable … ”

Now, as Pyne sits in the boardroom of his office high in Westpac House, from where he conducts his new career as a consultant, there’s an obvious question: Had they talked, could Turnbull have been saved?

“Well I’m certain he (Cormann) wouldn’t have changed my mind,” says 52-year-old Pyne, who quit politics after 26 years at the 2019 election.

“But I would have had a good chance of changing his. I think I could have bought more time, yes. That was a classic situation of the message not getting through to the front. We couldn’t get each other. It was bizarre, actually.”

By the time they did talk, it was too late: Cormann had told Turnbull he was going to back Peter Dutton’s challenge. Which paved the way for Scott Morrison’s victory.

Dutton, explains Pyne, didn’t know his place in the solar system.

In Pyne’s political universe, the sun is the prime minister, there are flashes of brilliance from passing meteors, and then there are the ministers and other senior players who make up the planets. It all works nicely when everyone knows their place. Dutton was an inner planet who wrongly thought he could be the sun.

Pyne’s book is also an account of how he went from Pluto under John Howard to “closer to Mercury” under Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull. And compared to Turnbull’s own recent book, A Bigger Picture, it’s a far milder assessment of the behaviour of his former colleagues in the mad period that followed the political demise of John Howard in 2007, as bitter personal feuds saw prime ministers and opposition leaders voted in and out with dizzying regularity.

Cormann – who pledged support for Turnbull then switched camps – was not “treacherous”, as Turnbull believes, says Pyne. He was “conflicted” between loyalty and a belief Turnbull would lose the election. “And I think it had a deep impact on him, and he chose in the end what he thought was right, which he thought helped the party win.”

This reluctance to condemn is one of the surprising features of the book. It’s rarely acid-tongued, despite the fact Pyne played politics hard – against Labor and with his own party’s conservatives over a quarter of a century. If you’re looking for him to unload on the likes of SA factional opponents Alexander Downer and Nick Minchin, whom he says “kept me down for so long”, you won’t find it. Even his mentor, Amanda Vanstone, in the foreword, says Pyne’s criticisms “seem fairly gentle compared to what they could have been”.

“It’s not a revenge book,” he says. “I didn’t want people to think he’s just trying to even the score or pay a few people back. Bitterness is a rather pointless emotion.”

Yes, Pyne does gleefully recount a few cases of gotcha, including working to “poleaxe” Nick Xenophon’s 2018 state election bid. But he keeps his stiletto mostly in his sleeve. One of his arch rivals, SA conservative Cory Bernardi, doesn’t even rate a mention – unlike many across the aisle he struck up friendships with, among them Anthony Albanese and Sarah Hanson-Young.

This apparent mellowing might raise eyebrows. Pyne is a polarising figure and even he admits people will laugh when he says he thinks internal party politics has been played too rough – “they’ll say he was one of the worst, most ruthless people in the party”. Some might also say: He’s in business now, no point aggravating old colleagues still pulling the strings.

Pyne’s new career includes two consultancies, one domestic and one international; a podcast interviewing well-known people; and running the Australia-United Arab Emirates Business Council he’s set up to further trade with one of our biggest Middle East partners.

And, for now, selling the book he says pulls back the curtain on the Canberra sausage factory, helped by notes he accumulated over decades in a pile of 20 binders.

He says the book is for ordinary people, like Bob and Nancy Stringbag, a mythical couple he thinks epitomise the quiet Australians whose views have guided his decisions in politics – a couple he says haven’t been to university, nor have they sent their kids there. He wants them to see what really goes on inside the Canberra “bubble”.

Given that it’s been regularly sprayed with political blood over the past dozen years, is that wise?

“We shouldn’t be embarrassed about it in a democracy,” he insists.

But shouldn’t we expect better? Constant fights for party leadership also make good policy a victim. Voters disengage when they think it’s all about the spoils, not the country.

Pyne is unmoved. “That’s our adversarial system,” he says.

“From courts through to politics. Every idea gets tested. And if you can’t make your idea stand up, you don’t win. So I don’t have any sympathy for that view. And it works. Because look at our country. COVID is a great example: When there was life or death, everyone came together. But ideas need to be tested, and if instead you’re not allowed to be adversarial … then bad ideas will be adopted.”

The fighting was one of his favourite things. The book is peppered with historical and classical warfare analogies, from Waterloo to the siege of Troy, and Pyne writes often that he considers himself a warrior. That’s another reason he backs the confrontational approach.

“I do think our system throws up the toughest people. It … tempers the steel as hard as it possibly can be. If you’re not tough you don’t make it, you go under the chariot wheels, and nobody reaches down to lift you up – they all think, ‘If that person is gone that’s an opportunity for me’.”

Still, Pyne says, “it doesn’t mean you have to be unpleasant or vindictive or venal … I’ve left politics with lots of friends, a lot of them are my competitors. It’s important to separate the personal from the political. But I always took the view that after the game there was no reason you have to hate your opponent. That’s why I find Trump so offensive. He has to denigrate everyone.”

Pyne says insults to him were water off a duck’s back. But it’s clear Julia Gillard got under his skin. Why? “Well, she called me a mincing poodle, which isn’t very nice,” he acknowledges. “I thought that was personal. And unnecessary. And she was trying to suggest that I was a bit fey.”

Fey? “It’s an old-fashioned description. Soft and a bit not up to the job. And I thought, ‘that’s nasty’. She and I always got along well before she was Minister for Education, but when you’re put together in that role, you can’t really get along with your opponent.”

Some people are more vulnerable than others. Albanese, Labor’s current leader, was one of Pyne’s strongest mates on the other side, and one whose political skills he respects. The pair first faced off when Albanese managed parliamentary business for Labor when Pyne was leader of the house in the 43rd parliament, from 2010-13, an unpredictable time where the Coalition ruled without a majority.

“Anthony and I spent a lot of time together,” Pyne says.

“There were moments there in the 43rd parliament where it could have gone either way.”

He means there were MPs under immense political and personal pressure – Liberal Peter Slipper and Labor’s Craig Thomson, for example – whose mental health was a concern. “I was worried about it and Anthony was worried about it and at least a couple of times we sort of said to each other, ‘You better take your foot off the accelerator here because you’re going a bit …we’re not going to push this poor person over the edge’.

“We were worried that somebody might take their own life. You don’t want politics to get to the point where it’s a matter of life or death, and we discovered over that time we had similar values, despite the fact he’s obviously a socialist and I’m not.”

Friends maybe, but Pyne isn’t endorsing Albanese as prime minister. “I think he’s very sentimental and I think that’s tough to be the prime minister if you are sentimental. You have to have a very dispassionate view of events to make a clear decision. That was the lesson from John Howard.”

Howard’s loss in 2007 to Kevin Rudd was the beginning of the tumult. Pyne had hoped it would be the beginning of great things for him. Since he’d arrived in Canberra aged 25, brash and bold, he says he’d been suppressed by Howard, Minchin and Downer.

It was 2003 before he got a very junior parliamentary post, then a few years later Howard made him Minister for Ageing. His comments back in 1993 to Howard, then canvassing for support for a leadership challenge, wouldn’t have helped his cause. “I said, ‘You’re yesterday’s man, we’ll never go back to you’,” Pyne recalls with a loud laugh. “He was only 48 by the way – and I am 52 now – so I must have been crazy.”

After Howard lost, Pyne believed his friendship with Peter Costello, who he expected to win the leadership, could help him win a vote for deputy leader. “I would have stood a slim chance,” he writes. “Without him, I had no hope.”

Costello decided not to run, devastating Pyne and triggering a free-for-all for the leadership that ran for the next decade and more. Pyne’s star did rise, but slowly. He got a junior, non-Cabinet shadow ministry from Brendan Nelson in 2007.

Nelson didn’t last as leader, unable to satisfy the moderates’ push for marriage equality laws and the conservatives’ opposition to climate change action.

When the job was thrown open in 2008, Pyne voted for Turnbull, who won, and was soon made shadow minister for education – against Labor’s Julia Gillard – and manager of Opposition business from early 2009, which meant he ran tactics and procedure in the House.

That gave him a spot in the party’s leadership team, where he stayed for the next decade – and the right to give his book its title. Like Nelson, Turnbull didn’t last. His support for Rudd’s emissions trading scheme, in the face of strong opposition in his own ranks, proved fatal. It was then Abbott’s turn, and he proved to be a formidable Opposition leader. Pyne might have been a Turnbull man, but he liked Abbott’s love of a fight. “I was in his inner circle and it was a rewarding place to be,” he writes. “He was exhilarating in battle and that’s precisely how he saw the contest with Labor, a battle.”

Abbott claimed Rudd as his first victim, when the Prime Minister was replaced by Gillard in a coup. That was 2010.

When Gillard was elected with a minority government, Pyne engaged in “war on all fronts at all times”. It was a “hideous” parliament, he says now, made manageable thanks to the relationship with Albanese.

The Coalition had its troubles, too. Howard had shown how to run a party room, Pyne says, by giving everyone the impression he was just first among equals, and letting others have their say. “It was a great strength and it kept him in place for 12-and-a-half years,” he says. “I didn’t see it replicated in any other leader I served.”

Abbott’s win in 2013 was Pyne’s crowning political glory. He was Leader of the House, and in Cabinet as Minister for Education. Education was tough, especially as Abbott promised no cuts in the election campaign and slashed in government. In the row with universities Pyne wad forced to backflip on money at one point, resulting in a disastrous interview in which he declared he’d sorted the problem because “I’m a fixer”. The nickname stuck.

Abbott created a lot of trouble for himself as Prime Minister, failing to heed the push for a conscience vote on marriage equality, breaking his promise on no cuts to key departments – and knighting Prince Philip. “In my opinion,” writes Pyne in trademark battlespeak, “that’s when the torpedo left the submarine and headed towards the aircraft carrier.”

Pyne was so disenchanted he considered getting out. The government was a mess, with leaks and animosity. Despite working closely with Abbott, he felt no longer trusted. He recalls a lunch with former Liberal senator Robert Hill at Chianti in Adelaide.

“I remember saying to Robert, ‘When you were in the Cabinet, was it fun?’. He said, ‘Well, of course. It was the best time of my life. Isn’t that the case?’. I said, ‘No, it’s not the case, it’s kind of a bit horrific. Government is a bit messy. And being in the Cabinet, I thought would be the pinnacle of my career, and actually it’s quite … not good. And I’m actually thinking about whether I should bother to go on’.”

Pyne insists he wasn’t part of any plot to bring down his leader, although he says he didn’t tell Abbott that Turnbull had called him to his house one night to say he was thinking of a challenge that week. There was no need to tell him something he already knew. Pyne writes: “Warned him of what? That Turnbull wanted his job?”

When Turnbull did challenge that week, Pyne backed him. In the subsequent federal election in 2016, Turnbull only retained government with a paper-thin majority. Pyne argues Abbott would have lost, “maybe his planet orbited in the great constellation of headkickers”.

Pyne admits he didn’t pick up the Dutton challenge to Turnbull in mid-August 2018. But Turnbull seemed to know something was up, because he called out his opponents at the party room meeting on Tuesday of that week. He didn’t ask Pyne’s opinion beforehand – Pyne says he would have rejected the idea, arguing power shouldn’t be offered, it had to be taken.

Could Turnbull have saved himself? “We’ll never know. His view was they were coming for him,” Pyne says. “From the moment Malcolm was elected prime minister there were forces working against him. And it took them three years to get rid of him. And whether it took them one, two, three or six they were never going to stop. They weren’t actually interested in what the government was doing, or whether we could win an election. There weren’t many of them but there were enough.”

But Pyne defends Morrison, who he says tried to save Turnbull by suggesting in a meeting between the three of them that they urge supporters to go home to their electorates once the House had risen that Thursday, the day before the vote.

“But it was just too late,” Pyne says. “You really couldn’t really pull it back. But it’s an interesting story because there’s this nonsensical theory propagated around the Canberra bubble that Morrison and his people planned this for months. We considered it, but I think Malcolm in the end said, ‘I think it’s all gone too far now’.”

Turnbull’s loss saw Pyne decide to go. He insists it wasn’t because he felt Morrison would lose, although to the world they both knew it would look like another rat deserting a sinking ship. “I wanted to do something new. Twenty-six years was long enough,” he says.

Pyne has since been learning new skills. He may have been Leader of the House in Canberra, but his wife and their four kids didn’t think that expertise was needed at home when he suggested a few changes.

“So Carolyn has run the house for a quarter of a century and now I’ve turned up. And everyone’s looked at me as if to say, ‘Well, we’re very happy to have you home, but you really can’t come in and change all the rules … you know you’ve really abrogated that role some time ago’.”

Writing the book has also meant time for reflection. Who were his most difficult opponents, I ask? Pyne puts them into categories. Labor’s Mia Handshin was his biggest direct threat, when she almost took the seat of Sturt in 2007. It was so close that several of his staff had given up.

“Inside the party, the most formidable opponent was Minchin, but … we respected each other,” he says. “I could tell him something and know it would not be repeated – tell him something about how to manage the party and he wouldn’t use it against me – and he could do exactly the same thing with me.”

And Labor? Tanya Plibersek was “formidable in Education”, he says. More generally there were “the dangermen, the people I think ‘I’m gonna have to be on my toes here’”. “It would have been (Mark) Latham, because he’s prepared to do and say anything.

“And Albanese. When going toe to toe in the chamber often for hours on end – which looking back now seems completely pointless but at the time seemed absolutely crucial – the person I was most concerned about in the chamber was Anthony because he understood the rules … they’re a tremendously powerful tool.”

Pyne chose to stick mostly with political shenanigans in the book. There’s not a lot on policy except for his time as Minister for Defence Industry, in which he says he managed the biggest peacetime military build-up in Australian history – one based around domestic shipbuilding, which will in time be an unparalleled boost to the SA economy.

You can’t help wonder, with his constant references to battle, whether politics to him was more about the victory than what you did with it. He says not, pointing to defence.

“What have I learned from politics?” Pyne says. “The lesson is to focus on outcomes and policy, to focus on doing things, not being someone … I have a whole chapter on defence because I was three years in the portfolio and it’s a good story about how you make a difference.

“The lesson is all the fighting in the party and at the elections is not why you’re in politics. All of that internecine party stuff which a lot of people think the politicians enjoy – the parlour games – only really matters to put yourself in a position where you’re actually able to do something. The last thing you want is to leave politics after a quarter of a century and say, ‘What did you achieve? Well, I managed to take over the Burnside branch’.

“It’s fair to say when I was a young politician I was a political warrior; by the time I left I was regarded as a policy warrior in defence. I learnt that lesson over time.”

The Insider by Christopher Pyne (Hachette, $34.99, e-book $16.99, audiobook $39.99).

Read an exclusive extract at advertiser.com.au from noon on Saturday and in

tomorrow’s Sunday Mail.