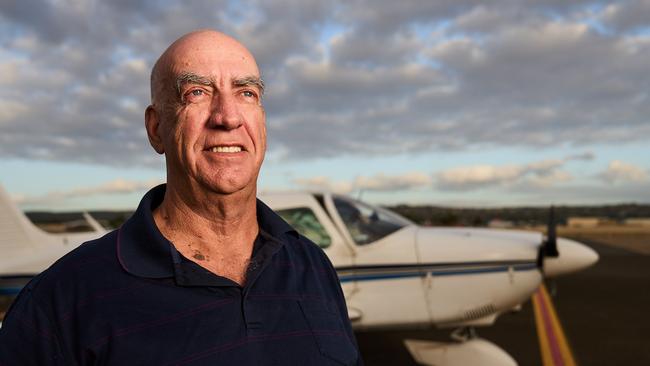

SA Weekend: Adelaide pilot Rod Lovell on his mission to set the record straight on the 1994 plane crash that saved lives but cost him his wings

SA pilot Rod Lovell saved his passengers but lost his career when he ditched his DC-3 in Botany Bay in 1994 – now he says he wants justice. Listen to this story as a podcast.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

You don’t forget the sight of a fatal air crash, not when you’ve flown over its smouldering wreckage as Rod Lovell did that afternoon at Sydney Airport back in 1980.

The twin-engine Super King Air had lost its left engine on takeoff and, in a frantic 108 seconds, the pilot looped around in a desperate attempt to land on another runway. He didn’t make it: unable to maintain altitude, the plane smashed into a seawall, its fuel igniting in a fireball that killed all 13 people aboard, including a week-old baby.

LISTEN TO THIS ARTICLE AS A PODCAST

The burnt shell of what remained of the small passenger plane was still smoking when Lovell landed his own plane about an hour later.

And then, 14 years on, all of it came roaring back to him with the force of a whack in the head.

Here Lovell was on the bright blue Sunday morning of April 24, 1994, lifting off from Sydney airport in a 50-year-old DC-3, to find that he had also suddenly lost a left engine – and was also losing altitude despite having the remaining engine showing full power.

Like the pilot of the Super King Air, he faced a range of life-and-death choices.

The ex-RAAF pilot knew if he got his next move wrong, he’d soon be dead along with the other 24 people on the plane in what would be one of Australia’s worst air disasters.

Should he try to turn and land, as he and his co-pilot Nick Leach had discussed before takeoff? Opt for the new runway still being built at that time? Or ditch in Botany Bay?

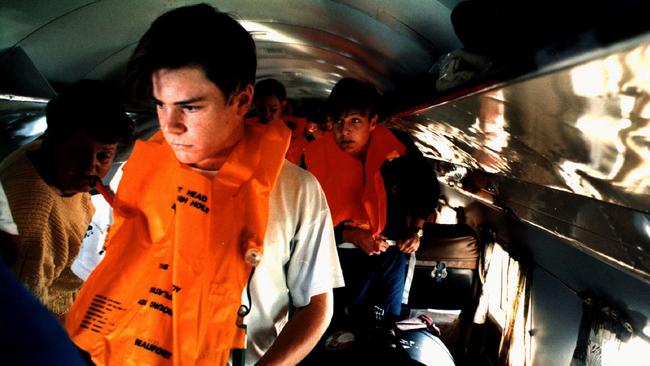

Behind him, seat belts tight, were the Sydney Scots College schoolboy band, their support staff, a few army personnel and some journalists, all bound for an Anzac Day Service on Norfolk Island.

The 1980 wreck was filling Lovell’s head.

“I cannot stress how powerful this thought was,” he recalls now. “And I’m just saying to myself: ‘This is not going to happen to my passengers, this is not going to happen to my passengers’.”

Twenty-seven years later, as we sit in his home town of Victor Harbor, Lovell is running through the events of that morning. Again. They have rarely left his thoughts in all the days since. The reason for that is what happened next: it was, he argues, a gross injustice that cost him his marriage and career.

Lovell did ditch the plane that day, just 46 seconds after the left engine failed. That decision saved the lives of everyone, and, for a brief time, he was hailed as a hero for his cool thinking and enormous skill preventing what would have been a terrible tragedy. But after the headlines faded, he came under the scrutiny of the Bureau of Air Safety Investigation (now the Australian Transport Safety Bureau).

Unlike Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, who ditched a US Airways Airbus A320 in the Hudson River after losing both engines when he struck a flock of geese above New York City in 2009, Lovell got no phone call from the nation’s leader, no Hollywood movie – and no allowance in the subsequent investigation for “human factors” such as shock in the amount of time needed to make his decisions.

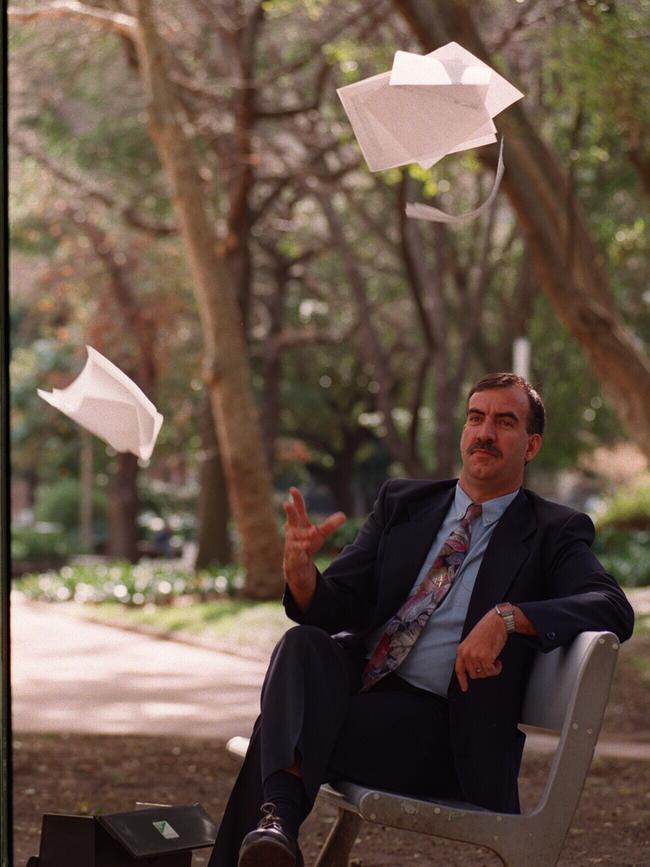

Instead, in his recent self-published book From Hero to Zero, Lovell asserts that investigators weren’t interested in his decision-making processes, or his insistence the right engine was faulty and therefore unable to gain altitude as expected.

Instead, he says, their unfair hounding prevented him from working again as a commercial pilot. BASI said the plane was badly maintained, overloaded, that the co-pilot was not sufficiently trained – and that Lovell should have known of the excess weight and Leach’s lack of qualifications. And, crucially, it found that when the engine failed, he should have taken over immediately which may have avoided a ditching.

Lovell rejected the claims. Then, about nine weeks after the incident when the Civil Aviation Authority took his licence away, he considered taking his own life, he says.

“I was in utter disbelief. I’d saved the lives of 25 people and they suspended my licence. You know, I am thinking: ‘Am I in a time warp or something?’ I could not gel what had happened.”

Lovell claims he was the fall guy: a scapegoat for a situation caused by a badly maintained plane that ought to have been overseen properly by the CAA. Instead, he says, it was easier to blame pilot error.

But writing the book, which he says sets the record straight, has turned his life around. For the first time in almost a quarter of a century, he’s happy to be flying again. And he’s determined to continue to clear his name.

“I will fight this until the day I die,” says the 71-year-old, spurred by the encouragement of many new supporters who have read his book or heard one of his talks now he is on the speaker’s circuit.

“I want the BASI report rewritten,” he says, “and I want some recognition for the job I did that day.”

Lovell grew up in Middleton and thinks he must have been three or four, watching planes dropping top-dressing on nearby hills, when he became keen on one day flying himself. He joined the RAAF at 18 as an apprentice flight instrument fitter, was advised to apply for pilot training, and soon was in the cockpit of Mirage fighter jets. Later he captained the long-distance P3-Orions out of Edinburgh.

Ten years in the RAAF and training that cost $1 million prepared him well for flying into trouble. One day over the ocean after a Mach 2 run (about 2500km/h) in a Mirage “all of a sudden it went quiet”. The engine “flame out” happened at 50,000 feet and it could only hope to reignite at 25,000 feet when the air was more dense.

“They say that a Mirage has the gliding properties of a brick, and that’s an understatement,” Lovell says of the plunge towards the sea that followed. “And I decided that if I didn’t get it relit, I was going to eject.” But the engine did relight, and Lovell took back control.

Scary? Not really, he says. “You just go back to your training; you really don't have time to be scared.”

Lovell was not the right personality for a fighter pilot. He preferred the teamwork that came with a crew, and found his niche on the submarine-hunting and surveillance P3 Orions working with 12 or 13 others. And, since 90 per cent of those flights were over water, “we used to practise ditching quite a bit”.

The practice would be at perhaps 3000 feet, obviously not in the sea. “Approaching and configuring an aeroplane for ditching is totally different to landing, it’s an unusual flight procedure,” Lovell says. “So we used to practise. This paid big dividends later in my life.”

It’s fair to say that Lovell is a stubborn man, who says what he thinks. He sometimes got into trouble in the RAAF because he never really accepted that higher rank meant better ideas.

That, combined with the prospect of a desk job and the lure of better pay in the commercial airlines saw him quit the military after a decade and work for a range of private operators, starting with IPEC in 1977 on DC-3s and later DC-9 jets.

He was a little too old for then-carriers TAA and Ansett which preferred younger recruits, although he did work for Qantas for a while as a Boeing 747 simulator instructor. That meant he was qualified to fly a jumbo, but he did not do so. Nor did he keep that job because Qantas shed a lot of staff after the 1989 national pilots’ strike.

Despite his expertise in modern jets, he loved the old World War II era DC-3s, workhorses which he still adores – “superbly designed, incredibly robust” – but which he says with the passing of time have fewer people who know how to properly service them.

He became a DC-3 captain in 1979, and by that fateful day in 1994, he’d been flying that particular 1944 plane, VH-EDC, for 17 months on various trips across the Pacific.

He remembers that April morning in Sydney was a beautiful day with a cloudless sky. The plane was operated by South Pacific Airmotive and one of the owners, also an aircraft engineer, was co-pilot. A third supernumerary pilot, Andrew Buxton was behind them in the cockpit. The passengers were mostly teenage boys, the band of Sydney school Scots College and staff, off to the Anzac Day commemorations on Norfolk Island.

After taxiing out at 9am, the plane lifted off heading out towards Botany Bay and, says Lovell, everything seemed normal. “The indications were that we had takeoff power of 1200 horsepower per engine, we lifted off, the co-pilot flying, and we selected the landing gear up. And then, at about 200 feet – it is hard to say – there are a couple of bangs from the left engine. The aeroplane swerved a little bit to the left …”

He alerted the Control Tower: “Echo Delta Charlie’s got a slight problem, we’ll just ah … standby one,” That was, he thinks, about 30 seconds into the flight at 9.09:04.

Checks confirmed the engine had failed, so the pilots followed procedures to shut it down safely. The co-pilot Leach was still flying the plane. The propeller wasn’t turning, but Lovell didn’t have time to check the position of the blades. The shut down procedure and confirmation probably took about 23 seconds from the time of the failure.

The Tower has asked if everything was OK. “Ah negative …” Lovell replied.

By now something else was apparent. Despite expectations that the plane would continue flying on its other engine, it was losing height. “I expect it to go up, and it’s not, and I realise it’s going nowhere,” Lovell recalls. He tells the co-pilot he must stick to 81 knots, but “it’s not climbing to the stars, it’s turning to worms, so what should I do?”

The situation was far from clear: the right engine instruments were saying it was delivering the power, yet the plane felt like a parachute had just opened on the tail, dragging it backwards. What did he think had happened?

“You really don’t have time to think,” he says. “If you’re at 40,000 feet you have time to analyse why; I didn’t. I think one of the secrets of flying, or anything like this, is you’ve got to prioritise. What’s the most important thing? If you get below minimum control velocity in the air, you lose control. So if I get anywhere near there, she’s going to spear over and crash and kill everybody.”

At this point, he tells Leach “You won’t get it”, according to the cockpit conversation intermittently recorded because of a stuck transmitter. Then, he says, he called out “taking over”, meaning he’d assumed control of the plane, although that is not on the recording.

But Lovell’s options weren’t good. There was the prospect of returning to the runway as they’d discussed pre-flight in the event of engine failure, but he didn’t know whether his landing gear was up or down yet (a quirk of the DC-3) and there were huge rocks in the sea wall at the end of the runway.

The new runway nearby hadn’t been finished, and machinery and piles of sand were on it. If he swung over to align to that, he’d lose height and speed which could prove catastrophic. At any moment, with speed washing off and the height now maybe 150ft, he could lose control of the plane. He had to lower the nose to keep up speed. One way or another, the plane would be back on earth soon.

And the smouldering wreck of the Super King Air was in his head.

All this flashed through in a couple of seconds, says Lovell. The only real option was the water. “So it’s easy, I’ll ditch the aeroplane there,” he recalls thinking. “Not a problem at all. Completely comfortable. And I say to the tower, we’re gonna have to ditch here.”

The trick was to get low and slow, almost to stalling speed, dodge a small boat, then flare up with lowered flaps and hit the water evenly – not easy with one engine out. If one wing had dipped the plane would have cartwheeled and probably killed everyone. Instead, it hit flat at around 60 knots, a mere 46 seconds after confirming the engine failure.

The impact threw up a huge bow wave that washed over the windows, making it seem as if the plane had submerged. The rotating right propeller dug into the water, with the force pulling the DC-3 around to the right and shearing the engine off the wing. In the cockpit Lovell was momentarily stunned when he hit his head on the windscreen, but then the pilots turned off everything.

“I remember thinking it’s going be absolute carnage down the back,” Lovell says. “I expected to see arms and legs and limbs and bodies everywhere.

“And I remember looking around and there’s all these kids standing up. They were very disciplined. There was no panic. Nobody was really talking. They were just putting on life jackets and I was so happy – I think it’s the most elated feeling I’ve ever had in my life.”

The co-pilot left via the escape hatch on the roof, while Lovell and the other pilot Buxton checked the cabin to ensure all the passengers had left. The only person injured was the flight attendant who had released her seat belt and sustained a broken wrist when she was thrown down the cabin on impact. The general calm and composure was recorded by two journalists from The Australian, writer D.D. McNicoll and photographer Chris Pavlich.

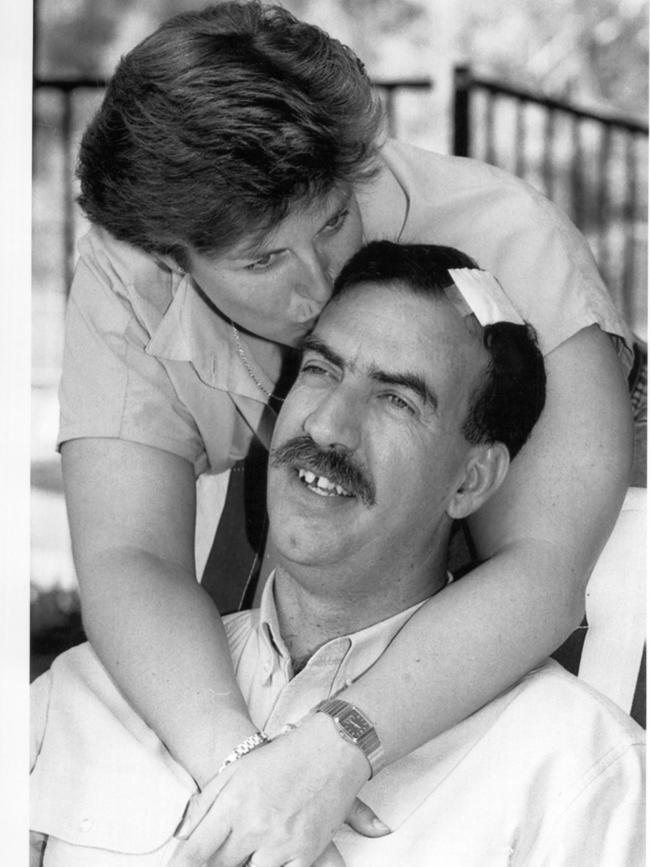

The pilots spent a few hours in hospital but were soon out. Driving home with his then wife Helen, also a pilot, he told her that if it was true everyone on earth was put here for a purpose, he’d just carried out his.

But that feeling of happiness did not last long. The air crash investigation, he says, did not see things his way. “The investigators, the CAA and BASI, were not interested one iota in what went on in my head, my processing about why I decided to ditch and not land on the runway,” he says. “They didn’t want to know.”

Nor, he says, did they show interest in his claim the right engine lacked power.

He says while the plane was lifted from the water in about three days, the right engine was left on the seabed for about nine weeks.

The BASI report laid no blame on the right engine, and discounted any serious drag from the fact the broken left engine’s propeller did not stop in the correct “feathered” position to minimise air resistance.

It said the problem was that the plane was overloaded by about half a tonne and that when the engine failed, the co-pilot didn't have the skills to handle the emergency. It said Lovell took too long to take control – and suggested had he done so sooner he might have been able to keep the plane going up and land on a runway. As it was, ditching became the only option available. It also said he should have known the plane was overloaded, and that his co-pilot’s qualifications were not what he believed them to be.

When investigators pulled the right engine apart, cleaned all the spark plugs they could find – 25 of 28 – 11 of them were found to be unserviceable. Yet that was not considered relevant.

BASI did share the blame around – the operators for poor maintenance, the CAA which had allowed both engines to operate beyond their major overhaul (only one should have been at any time), and the co-pilot whose qualifications were not they should be.

But Lovell was furious. He was sure he’d done nothing wrong. He had accepted that the weight listed was correct and that his co-pilot was truthful about his qualifications. In any case he witnessed no errors by the co-pilot that day before he took over. Nor would the extra weight claimed by BASI have stopped the plane flying on a full-powered single engine, he says.

The blow came when the CAA told him he needed to attend counselling. “Counselling isn’t, ‘You’re suffering PTSD, do you want a chocolate milkshake?’,” Lovell says. “It’s that they believe I’ve done something wrong.”

His legal advice was that by attending he’d be admitting he made a mistake. So when he was told counselling was necessary he replied: “I totally agree – so when are you going to undertake it?” That, he admits, “pissed them off”.

That’s when he got the ultimatum: no counselling, no licence. He lost his licence but regained it in the US shortly after, and the CAA was forced to accept that. But when bush pilot Dick Lang in South Australia hired him in 1995, he says CAA pressure on the business led him to resign.

In 2008, he was almost selected by the Royal Flying Doctor Service in NSW, but that state’s health department refused the offer because of the 14-year-old BASI report, he says.

Lovell ended up in a string of jobs like packing shelves at a supermarket warehouse. His marriage to Helen – his second – ended. He complained to everyone he could think of including the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the federal Aviation Minister at the time, John Sharp. He says he got nowhere.

“I felt my guts and passion had been ripped out. And I was so furious and angry. I never looked at another aeroplane. Every pilot looks at an aeroplane overhead; I never did. I just shut down aviation, it was no longer a part of my life.”

Lovell feels he wasn’t the only one hurt by the CAA. Had the BASI report gone into the issues he raised, he says, they may have helped to prevent the crash of a DC-3 in the Netherlands, which killed 32 people, after an engine failed and the pilot sought to make it back to the runway after flying back over the sea, rather than ditching.

The report into that crash discounted overloading of 240kg as an issue, but did consider the impact of drag from the stationary propeller on the broken engine, and also recognised that the pilots had little time (three minutes) to mentally adjust to a rapidly deteriorating situation – which Lovell feels he never got, even though he had much less time.

“A factor to be considered is the hypothesis of the pilots that a twin engined aircraft like the DC-3 is able to be safely operated with one engine inoperative and is capable to maintain altitude and a safe airspeed,” the official Dutch investigation says. “This hypothesis is built and strengthened during their airline pilot career. In this case, with a not fully feathered propeller, it was a false hypothesis. In a high workload situation, realising that it was a false hypothesis takes time, which was not available.”

The Dutch crash led to the building of a DC-3 simulator, which Lovell was invited to Europe to fly. It vindicated his position, he says, because when loaded with the weight the CAA said his plane had, it flew well on one engine – until that engine was degraded by 30 per cent of its power. And that, says Lovell, justifies his view that the right engine was faulty, as the spark plugs suggested.

The investigators still disagree. At Lovell’s request last year, a review was ordered by the Air Transit Safety Board and carried out by “a highly-respected former senior transport safety investigator”. But, says an ATSB spokesman: “The review did not find any substantive new or pre-existing evidence to indicate or suggest that the accident occurred as a result of factors not otherwise identified by the BASI investigation. The investigation was not reopened.”

Despite that disappointment, Lovell says his life has changed for the better thanks to the book. Just holding it made him stand taller, he says.

“I hoped to sell 200, and I’ve sold more than 1000,” he says.

But it’s the reaction of people that has surprised him. “I give a talk and they come up to me and say, ‘How can we help you?’,” he says. “I’ve got thousands of people now who’ve listened to me, believed in me, and you know what they’re saying? ‘Stick it to them Rod, you haven’t done anything wrong.’ A friend of mine said, ‘Rod you’ve changed enormously in the last 12 months’. I notice too – I feel like I can conquer the world now.”

So much so that six months ago he bought a share in a Piper Archer, a single engine four-seater plane at Parafield. For the first time in 25 years he’s enjoying flying again.

“It was like putting my hand in a glove,” he says about renewing his love of the freedom of flight. “It feels great, absolutely superb. I’m on cloud nine again.”

But he’s not forgotten, or forgiven. “People asked me, who and what caused the aeroplane to crash? What caused it was the incredible lack of maintenance. Who caused it was the CAA for not doing their job of overseeing that maintenance, which they are chartered to do.”

Yet, given the way his life and career were ruined in the aftermath, would it not have been more politic to have attended the CAA interview back in 1994?

He shakes his head.

“I may be stubborn, but I like to think I’ve got principles,” he says. “So no, I would not. I wouldn’t change anything – I still would not roll over.”

From Hero to Zero is $29 plus postage and handling at fromherotozero.com.au