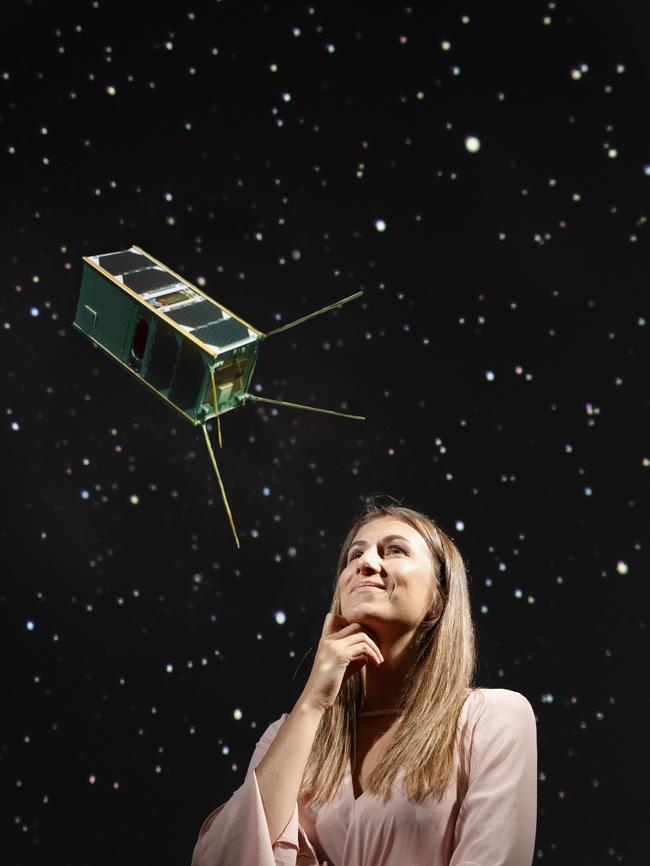

Rocket woman – meet Flavia Tata Nardini, the European scientist who is helping blast SA higher into the space age

MEET Flavia Tata Nardini, the European scientist who came to Adelaide for love and is now helping blast SA into the forefront of a revolutionary new commercial space age.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MEET Flavia Tata Nardini, the European scientist who came to Adelaide for love and is now helping blast SA into the forefront of a revolutionary new commercial space age.

She was an Italian rocket scientist working in The Hague when she fell in love with a handsome engineer who was in Europe on assignment. Stefano Landi was Italian, too, but he came from Adelaide.

“He was there working on some software, nothing to do with space,” says Rome-born Flavia Tata Nardini. “After one year he said to me, ‘you should come to Adelaide to live’ and I said ‘OK, let’s do it’. It was quick!”

This was 2012. Tata Nardini had a master’s degree in space engineering from University La Sapienza in Rome. She had worked at the European Space Agency in The Netherlands and was now with a Dutch innovation company, TNO, building engines for rockets.

She had little idea what to expect from Adelaide but she has a vivacious personality and she seems remarkably fearless.

“I knew that Adelaide was very relevant for engineering and I would find a job, that’s what I had in mind because I had all this amazing experience,” she says.

At the time there was only one space start- up in Australia, based in Sydney, so she wasn’t expecting to be able to build rockets but she thought she would find something to do. “I am super-qualified,” she says with no hint of a boast. “When I met him I was leading a million-dollar project and it was to Mars so I thought it would be a piece of cake.”

They came to Adelaide and had a baby girl, Caterina, who is now four and a half. Tata Nardini took care of her then started looking for a job, only she couldn’t find one.

She and Landi were married in 2016 but it takes four years to qualify for an Australian passport, which locked her out of Defence where all of the advanced engineering work was going on.

“It was depressing, I thought I was smart!” she says. “This is very much a defence state, so from BAE to Lockheed, you need to have security clearance to work there.”

Instead of becoming the most highly qualified housewife in Adelaide, she started her own space company, Fleet, which will next year launch the first of what she hopes will be an initial tranche of 100 miniaturised satellites. The flow-on effect of this incredible initiative has been the birth of a commercial South Australian space industry. Virtually on her own she has opened the state’s doors to a new commercial space future.

“Adelaide has a really good shot at being one of the leading (players) in the new privatised space industry and Flavia’s company is at the forefront of that,” says influential American author and innovator Robert Tercek who will be in Adelaide in October as curator of the inaugural tech festival, Hybrid World ADL.

“She is at the forefront of leading Adelaide into the space age.”

Just as a car factory attracts ancillary industries that cluster nearby, so Fleet’s initiative is proving a magnet for space industry mass. There are now 60 South Australian organisations with actual or potential space expertise, including the start-up Myriota, which specialises in satellite communications and this year won an award in Silicon Valley. Space investment in the past six months is running at more than $10 million with one company, Neumann Space, moving here from Sydney. From the sole Australian space start-up when Tata Nardini arrived, there are now 45. The State Government, alert to the potential of turning South Australia into an innovation hub, loves the concept and is pitching to become the operational base for a much-needed national space agency, based in Canberra.

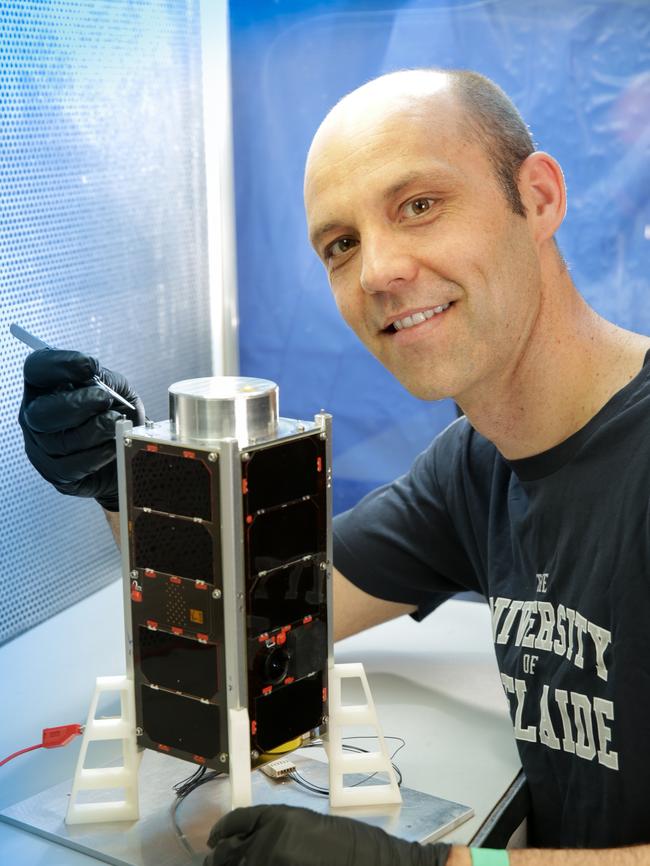

Fleet grew out of her meeting Dr Matt Tetlow at the University of Adelaide where he was working on the QB50 CubeSat, a miniaturised satellite which is now in space, one of an international network of 50 data-collecting nanosatellites launched from the International Space Station and commissioned by the European Union. Then they met Matt Pearson, a space entrepreneur.

“We thought ‘why don’t we create an industry that doesn’t exist?’” says Tata Nardini.

This was the start of 2014. They felt their way first by working together on the space education initiative, Launchbox, which was dedicated to engaging school students with science and space.

They would come into schools and, over a term, guide students through the process of building a simplified CubeSat created from a 3D printer.

They were taking a small step towards fixing the demoralising gap between the average Australian student’s lacklustre engagement with the STEM subjects – Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths – here and in Europe. The lag applies particularly to girls, and it is a huge national intellectual deficit. In Europe female students embrace STEM so it is not surprising it took a woman scientist educated in Italy to launch the state’s commercial space industry.

“For Italy, and for Europe in general, a woman being an engineer is not so amazing,” Tata Nardini says. “I found the difference between there and here huge and I didn’t expect that. It’s the culture.”

Tata Nardini has loved space since she was tiny. She comes from a family of engineers where the women were as driven as the men and her grandmother had a degree, her grandfather two. She would write to Father Christmas asking for space books, or a telescope. She wanted to be an astronaut from the age of five.

“When I got to 15 or 16, I thought I’ve got to do something different to do with science, and I really loved space, I loved rockets,” she says. “I was just fascinated. I think I’ve always wanted to do this.”

At her university in Rome, about 40 per cent of the students in advanced maths and chemistry classes were women. Her group started and finished together and when her master’s degree was done she moved with most of them to The Netherlands to work at the European Space Agency. They found jobs but the work environment in Europe is very competitive, with large numbers of bright people competing for skilled work.

She wonders if Australia’s isolation and lifestyle contribute to our science apathy.

An attitude of “why bother?” stops most teenagers but particularly girls from doing the hard subjects – the so-called “suicide five” of two maths, chemistry, physics, and biology. “We are a happy country here,” Tata Nardini says. “In Europe it’s harder and there is more competition. For example, you would not dare take a year or six months off on maternity leave.”

At the European Space Agency she was working on thrusters for CubeStar, which meant building little engines for little satellites. The miniaturisation of space is the pathway to the future and Tata Nardini was working with satellites that were densely packed with layers of printed circuit boards, and they ranged in size from 10sq cm to 40cm by 30cm, about the size of a handbag. Her job was getting them to move, which meant miniaturising an engine to very small dimensions.

She was perfectly positioned to see how space was being revolutionised and how the future was going to look very different. This shift is so remarkable she likens it to the evolution from a computer that took up a room, to a smart phone or iPad.

“Instead of one big eagle you have a lot of bees,” Tata Nardini says. “Small, very hi-tech miniaturised technologies can create a little satellite that can do the job of a big one and many of them can cover the whole Earth.” For a start, it changes the way the space industry does business. It marks a complete break from the old thinking of a satellite that takes a decade to build and costs $1 billion to launch, to something smaller, cheaper and more accessible. This disruption has taken the future of space away from the government-funded space agencies who were the only ones who could afford it, and into the hands of space entrepreneurs, like Elon Musk, and Tata Nardini.

“About five years ago they started to say, ‘hey, this is an amazing concept that we can use commercially’,” she says. “So space is not just for government and defence, it’s for everyone.”

To see how much has changed, just a decade ago NASA invested $260 million in the American company Kistler, which planned to use South Australia’s Woomera base to launch a commercial K-1 reusable rocket to service the International Space Station. The company had significant infrastructure, an office in Woomera and commercial investors on board. It went bankrupt before a single rocket was ever launched. Companies like Fleet are revolutionising that landscape.

Launchbox was a labour of love. A six-week engagement with a science class would culminate with the launch of a simplified CubeSat using a hot-air balloon. It would travel up about 40km to the very edge of space, take photos and measurements then come down in a trajectory so the students could retrieve it and track the data.

“We weren’t funded, we were doing it off our bootstraps,” she says. “We were selling the kits and we did our own stuff, and it was really good fun because space is the kind of thing that no matter what age you are, you just love it.”

By now Tata Nardini, Tetlow and Pearson had bonded as a team and they wanted to find a mutual commercial purpose. The answer lay in the internet of Things. The IoT is the revolution flowing on from the miniaturisation of space and it refers to a new era of low-data communication between objects, using sensors. Just as technology spent a decade working out how to connect people with each other – the internet of people – so the next phase will be to connect inanimate or unintelligent objects: things. Thousands of sensors will record anything from the temperature inside food transport trucks, to moisture levels in the soil in a vineyard.

The problem had been connectivity. The infrastructure has not existed to allow a farmer with 10,000 sensors on two properties in South Australia to monitor on a smartphone app what was happening from the other side of the world. But a swarm of buzzing nanosatellites can connect sensors that will let him do just that, and at a reasonable cost by using less hungry, low-data connections.

“People demand a very high speed internet but these (sensors) connect at very low data so if we tried to use the infrastructure that we have now, it’s not going work. I mean your phone battery dies after one day,” Tata Nardini says. “So imagine a low data system that deploys 10,000 sensors? You need a different type of internet and this is what we are creating.”

This connectivity is already happening, particularly in agriculture. John Deere, one of the largest makers of farm equipment, has started pioneering self-drive vehicles and tractors that are data connected. Estimates are that in agriculture alone, IoT installations will grow by 20 per cent year on year for the next five years. It is game changing.

“They say there will be 75 billion devices coming online,” Tata Nardini says. “Not even two billion are connected now so it is a giant shift.”

The demand for this is not driven by the added convenience. The IoT will overhaul product quality management and make food production more targeted, with less waste. Enormous sums of money are at stake. Imagine sensors inside shipping containers controlling the transport of perishables where 40 per cent of the food is currently spoiled, or sensors maintaining safe conditions for live animal transport, or sensors that tell a farmer when to water or when it is optimal to sow.

Precision agriculture alone offers enormous and visible financial potential, so much so that the venture capital enthusiasm for Tata Nardini’s proposed satellite company – effectively creating the digital nervous system needed for the IoT – was enormous. While the internet evolved relatively slowly with demand being created after technology came online, the need for the IoT already exists and demand is pent up.

“The world needs this,” Tata Nardini says. “Industry needs to change the way that it operates and the enabler is connectivity.”

Fleet, with Tata Nardini as chief executive, Pearson as chief operating officer and Tetlow running the technical side, has so far raised $5 million. Eighteen months after its first capital raise of $25,000 was backed by a $50,000 State Government grant, they got $5 million from Australian investors, including Blackbird Ventures, Earth Space Robotics, Silicon Valley’s Horizon Partners and Mike Cannon-Brookes, an Australian billionaire who heads software company Atlassian and whose tweeting to a “legend” mate helped confirm Elon Musk’s interest in installing the world’s biggest battery in SA. “They’re rare, but every so often an idea (crosses) your path that really gets the adrenaline pumping,” Cannon-Brookes said of Fleet’s proposal.

“None of us could believe it because people kept saying ‘you should move to the US if you want to run a space company, you can’t stay in Adelaide’,” Tata Nardini says. “It turns out they were wrong.”

Fleet’s customers are not the end users but the providers of the sensors who need her network to enable what they sell.

Since March, Fleet has opened an office in Beverley with 17 staff, and offices in LA and in Europe. “We have customers all over the place,” she says. “Our end users are there and we need to be close to them – and space is a very complicated operation.”

Demand for positions was so strong she had 400 CVs to fill nine jobs, mainly from people in universities who wanted to join the new space race.

The initial capital raise will fund the first two Fleet satellites, which will go up early next year, from a launch pad soon be announced. A revolution in rocket launch capability is also underway with new providers springing up to meet the unfurling demand. Groups are establishing around the world, including Rocket Lab in New Zealand who Fleet is working with, and Gilmour Space Technologies in Queensland. Tata Nardini eventually wants to send her satellites up in multiples, maybe once a fortnight, so the first 100 could be in place by 2021. The IoT is a runaway train and you have to keep up, she says.

The biggest hurdle will be to launch the first two and then to work closely with their customers to troubleshoot as they go.

“Always the first three or four will be fine tuning but they will be commercially viable from the start,” she says. Once the first two are up, Fleet will return to investors with proof of concept to fund a second round of capital to propel them into a securer future.

Five years on, Tata Nardini likes Adelaide. Fleet operates out of a very cool hi-tech warehouse space with a vast polished concrete floor dotted with shipping containers where technicians build satellites under controlled conditions.

She had her second daughter, Vittoria, now two, the week after she founded Fleet and went virtually straight back to work. That was an interesting month, she says, one she won’t forget.

Her cleverness took a while to be discovered but she is now cutting through not just nationally, but internationally. Her open letter on Australia’s need for a national space agency – not just for the IoT but for space innovation in general – was widely noticed and not long after, federal Industry Minister Arthur Sinodinis spoke in support of an Australian agency and announced a review into Australia’s space capabilities, which will report next March.

“When I go abroad and say we are creating an Australian system of innovation, I don’t want to answer the question ‘but you don’t even have a space agency?’,” she says. “It’s kind of embarrassing.”

In the next couple of months space is coming here. As well as speaking at Hybrid World ADL (October 4-8), she will be part of the largest annual gathering of space professionals in the world which will this year be in Adelaide, the International Astronautical Congress from September 25-29. It will be the third time she will get to see space entrepreneur Elon Musk in a year.

She was part of a small space group who met him in Adelaide in July when he announced the world’s largest battery and just before that, she heard his keynote speech at an International Space Station research and development conference in Washington. His connection with South Australia is a wonderful piece of serendipity.

“It’s huge. What he is doing with the power and Tesla is really good and he has a lot of companies and a lot of potential for us,” she says. “He is such a visionary and he’s not afraid to try things so having him involved with South Australia is good for us as well.

At the IAC in Adelaide in late September, Musk will update the world on settlement on Mars in a speech that will live stream internationally from Adelaide. Tata Nardini will also speak on what Fleet is doing and she will welcome to her home town most of her subcontractors and partners who are coming as delegates. “It’s such an amazing year, 2017,” she says. “This is the year that space high-level innovation has begun.”

Best of all, her girls are growing up with a mother who is a rocket engineer and launches her own satellites. They are used to being in the warehouse, seeing satellites being built and being interested, particularly Caterina, in what is going on.

“They are beautiful girls and they see me doing this,” she says. “I mean, I worked from home for two years without a salary, and they were under my legs. I was doing teleconferences with the States while the kids nap. This is what I have done for two years!” ●

Flavia Tata Nardini will speak on ‘21st Century Agriculture begins in Outer Space’ at Hybrid World ADL, Thursday October 5

SKY’S THE LIMIT

A new State Library exhibition explores SA’s early role in the space race

In the late 1940s the Cold War between the Soviets and the West sparked a weapons rivalry that a decade later led to a fight for space dominance. The UK lacked an expanse big enough for missile testing but an enterprising High Commissioner in London suggested Woomera, which also fitted prime minister Chifley’s agenda for nation building, says space historian Kerrie Dougherty, curator of the Woomera 1955-1980 exhibition at the State Library running in conjunction with next month’s International Astronautical Congress. “It was a long way for the Soviet Union to try to spy,” Dougherty says.

Woomera Rocket Range became the largest overland weapons testing range in the western world. “Maralinga (also in SA) was where they were developing the bomb and Woomera was where they were developing the delivery system – long range missiles,” Dougherty says.

Dougherty loves Woomera, a dry outback town steeped in space history which is still the largest land-based weapon testing range in the world, run by Defence. When the Space Race began in the late 1950s, Australia hosted NASA tracking stations, launched scientific research rockets and launched an Australian-built WRESAT satellite.

But eventually its prominence waned, partly because newer satellites needed an equatorial trajectory instead of the polar launch Woomera offered. “That’s why French Guiana is a great place ... Woomera is too far south to get that advantage; you would have to use so much extra fuel,” Dougherty says.

The State Library exhibition includes a sample of Apollo 11 moon rock, presented to Australia by the US in recognition of the role that Australian tracking stations played in the Apollo 11 mission in 1969.

From Outback to Outer Space: Woomera 1955-1980, August 23-November 12, State Library of SA. Dougherty’s book, Australia in Space, will launch during the IAC, $64.95, ATF Press