Peter Cosgrove’s apology to Andrew Knox for bullying and bastardisation at Duntroon

Why Sir Peter Cosgrove made a phone call more than five decades later to say sorry for his role in a system of bullying and bastardisation at Duntroon Royal Military College.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Former Governor-General Sir Peter Cosgrove has apologised for his part in a system of bullying that shattered the military dreams of an Adelaide man and forced him to quit Duntroon Royal Military College. Penelope Debelle reports.

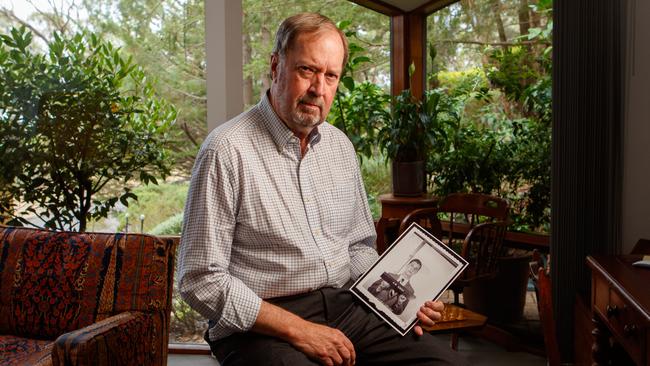

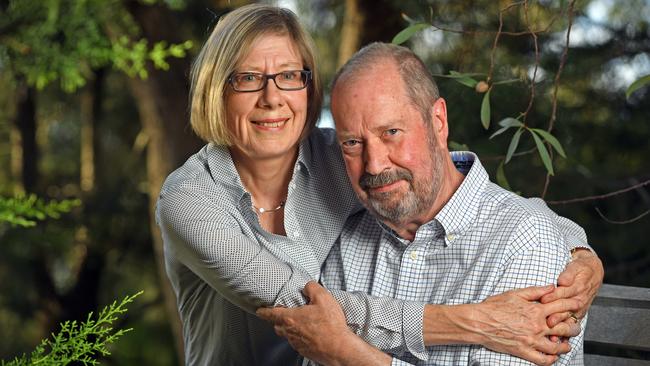

Fifty-three years after Andrew Knox left Duntroon on the brink of a breakdown after being bastardised by senior boys in the military, Sir Peter Cosgrove rang to apologise.

Cosgrove, Australia’s Governor-General from 2014 to 2019, accepted his role in the ritualised bullying and bastardisation that forced Knox out, crushing Knox’s spirit and leaving him with a sense of shame and hollowness that persisted through his adult life.

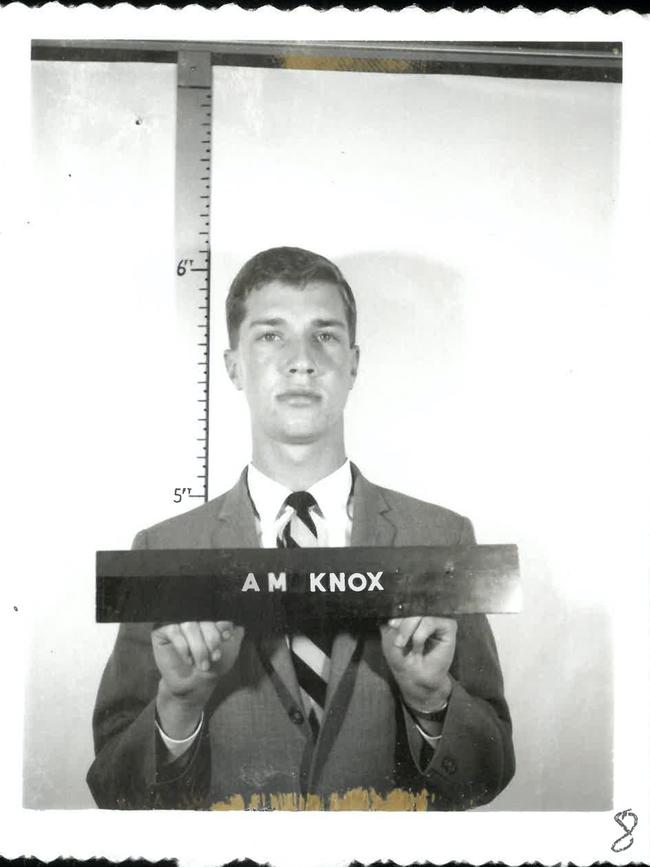

Knox, then 18, came from a World War II military family and his older brother Richard had graduated from Duntroon Royal Military College the year earlier. The shame of failure, of not being able to cop the bastardisation that was part of Duntroon’s rites of military passage, sat heavily, and not just with Andrew. His father, who had been so proud to have both of his sons join the military, never got over it and became hostile. Richard, who had tutored Knox in the details of procedure and how to look after your kit, also turned against him, and the ruinous effect on the family was lifelong.

In 1967, Cosgrove was 19, three years ahead of Knox at Duntroon and admits to participating in the bastardisation system that was seen then as integral to the teaching of military discipline through chain of command. Cosgrove was already showing signs of the leader he would become and others looked to him, Knox says.

During the surprise phone call Knox, now 72, took at his Adelaide home in September, Knox put it to the former Chief of the Defence Force that he had been part of a “brigade of terror” with others in his year.

That could have been somewhat the case, Cosgrove said. “It may have been some of that, to be honest, I think I was a bit of a dickhead actually,” he told Knox. “I know that the system was such, but I was a practitioner of that and I take no pride in that. It was ill judged.”

During a long and civil conversation, in which Cosgrove invited Knox for coffee when he next came to Adelaide, Cosgrove also apologised for his role in the breakdown of relations with his family.

“It was a tragedy in my view and I’m very, very sorry I had any part to play in it and I apologise,” he told Knox.

Knox maintains that Cosgrove and others in his year imposed an especially punitive form of bastardisation as a form of payback for what his brother had done to them when they had joined. While Cosgrove disputes that Knox was treated more harshly than others, Cosgrove was in the year subjected to ritualised bastardisation by Richard Knox and his peers.

“From where I stood, Peter Cosgrove had a couple of mates who had an axe to grind with my brother, probably justifiably so, and they singled me out,” Knox says.

Best known after a career in advertising and industrial relations as an advocate for fellow victims of the chemotherapy underdosing scandal in Adelaide, Knox knew what he was getting into at Duntroon, or at least thought he did.

“I knew a hell of a lot about how it should have been; half amusing, some a bit tough but more just a good laugh,” Knox says. “But this was different.”

Knox says he was deprived of food by being sent on fool’s errands while meals were served, he was made to jump on and off a wall until he fell down, he was doing hundreds of push ups a day while being yelled at and degraded and on one occasion had to crawl to a camp theatre two-thirds of a kilometre away on his hands and knees barking like a dog. Isolated from friends and family and with nowhere to escape, Knox was on the brink of breakdown.

“I couldn’t move around anywhere, I couldn’t get anything to eat, or in the mess I was forced to eat foul combinations of sauces, chutney and mustard mixed together on a spoon,” he says. “My classmates could give me no support whatsoever; they would have been complete idiots if they got involved.”

Speaking in the aftermath of his memoir published late last year, You Shouldn’t Have Joined, which devotes a few paragraphs to bastardisation, Cosgrove denies he was a ringleader, or that he singled Knox out.

“It’s silly to say ‘I am going to pick on this guy because his brother was somewhat harsh’ – they were all harsh, they were supposed to be harsh,” says Cosgrove. “I am quite clear that I didn’t have a special thing for Andrew.”

However, Knox recently obtained his Duntroon file, which includes an internal report about the affair that confirmed the view that an anti-Knox gang had been formed and that the army padre in particular had been disgusted with the “sadistic” treatment.

The names of the bullies were largely redacted, including a paragraph saying, “The leader of the anti-Knox gang appeared to be (blacked out).” Cosgrove is named at the end of a description of physical bullying, 800 push ups, the crawling incident and “putting (his) nose on (the) mess table while Cosgrove sprinkled pepper all around it”.

Cosgrove says he was never a member of any anti-Knox gang, had no recollection of any of these incidents and considered the description of the pepper incident “bizarre”. He says he was never approached by any padre over the matter.

Another confidential minute to the Army Commandant just before Knox was sent home concluded that “regrettably there appears to be a great deal of truth in what the boy says” and said that “a small group may have disgraced themselves and the system”.

In his book, Cosgrove writes of the “notorious but now thankfully defunct practice of bastardisation” and says he copped it and certainly handed it out but that the system was flawed. “Being a closed system – operated by cadets within the cadet body, with virtually no supervision or intrusion by the regular army staff – potential excesses could and did occur,” he writes.

Knox’s aborted military career seemed to be just a painful episode in his past but it resurfaced three years ago only through the remarkable coincidence that Knox, then preparing for the foreign donor, stem-cell transplant that saved his life, was staying at the same hotel in Melbourne where a Duntroon Class of ’67 reunion was to take place. He had been contacted years earlier for a similar event but felt too much shame to attend.

This time, Knox went. He was too sick for the reunion but caught up for a barbecue on the first night and instead of feeling shame, he was overwhelmed by support for what he went through. Many classmates harboured strong memories of his mistreatment and some had an accompanying sense of shame.

“One of them was sitting next to me at dinner and said when Cosgrove got his knighthood, he wrote to him and said, ‘Give it back, you remember what you did to Knox’,’” Knox says, although Cosgrove says he has no recollection of the letter. “It was a bit of an epiphany for me.”

Another former classmate, David Mason-Jones, a NSW businessman and freelance journalist, also wrote to Cosgrove, after reading a newspaper article in which a colleague of Cosgrove’s claimed he had not been a bully at Duntroon.

“I said in the letter that I respected what he has done for national life but I dispute that he wasn’t a bully,” Mason-Jones says. “I gave a couple of examples and said Andy Knox was a specific example of that.”

In September, knowing Cosgrove’s memoir was imminent, Knox contacted his classmates for their views. One respondent said Duntroon wrecked him emotionally and mentally and his later descent into depression was a consequence of what happened, not just to Knox, in 1967.

Another said his failure to step into the fray to help Knox had always bothered him. “I have always loved the college but it had a flaw that allowed bullies and those who lacked empathy room to manoeuvre, and you were perhaps one of the persons most wronged by that flaw,” he said.

Another who had attended the 2010 reunion told Knox his wife had been amazed at the consensus in their class about Knox’s treatment. “There were some nasty people … and we had two of the worst in Kokoda Company,” he wrote.

One said that the immature behaviour of Cosgrove and a handful of others was encouraged, and another, an author and historian, offered to help Knox approach Cosgrove if he wished.

“Peter Cosgrove was without peer (one of) the most ardent bastardisers in our time,” he wrote. “But he was at the sharp end of a system which had been going for 40 years.”

Apart from denying the events above, Cosgrove says he continues to maintain his regret and apology to Knox, and “any others who felt aggrieved from my attitude and actions from those times, 53 years ago”. Cosgrove says the system was meant to inculcate military discipline but excesses occurred and he was one of those who – unfortunately, he says – applied what he came to believe quite quickly was a flawed system.

“Where you have bastardisation, you are asking immature people to apply a closed, opaque discipline system to, in those days, school leavers, younger men,” he says. “That’s where its flaw was, that’s why it went off the rails and that’s why it was quite properly abolished.”

When it was abolished is a point of argument between Knox and Cosgrove. Knox’s former class in 1969 was caught up in its own bastardisation scandal when Duntroon lecturer Gerry Walsh was so appalled by what he saw being done by Knox’s year – now taking their turn to be the perpetrators – that he wrote to the commandant, triggering the first of many inquiries into military bullying and abuse.

Cosgrove says the practice was stamped out back then. “I think it was spectacularly stamped out in 1969 because heads rolled over it, and the controls that were put in there after that were very strict,” he says. “I reckon it evolved from 1969 as a punctuation mark, rule a line there.”

Knox disagrees and is critical of Cosgrove for failing to spearhead a culture that actively disowned bullying and bastardisation when he became Chief of the Army in 2000 and Chief of the Defence Force in 2002. He says Cosgrove was wrong to say it stopped back then; instead, it moved through to the Defence Force but became much more complex because female recruits were involved. Knox points to repeated scandals, in 1992 and again in 2011, and says it was clearly still a cultural problem on Cosgrove’s watch. He says Cosgrove’s view it had stopped was at odds with that of his immediate successor as Chief of Defence, Sir Angus Houston, who, as a first statement in 2005, committed to reforming the system he just inherited from Cosgrove, promising to stamp out abuse and bullying “with vigour and with speed”.

“Cosgrove had the ability to make change within the Defence forces, he had the ability to decry bastardisation in any form as complete anathema to the development of good leadership,” Knox says.

“He should have been providing greater leadership on this during his time when he had the power. It’s not enough to say he stopped it when it was in front of him – he should have been leading from above to stamp it out.”

Cosgrove rejects this and says he would not put up with “oppressive behaviour” when he encountered it. “I think that might be personal on your part,” he says when asked if he thought he had done enough. “I have a long record of being vigilant and proactive where there has been oppressive behaviour. There is a threshold, you cross that and it becomes unjust and unacceptable … I would not say that I was negligent in bringing to book people who cross the line.”

In another coincidence that brought this to a head for Knox, not long after the reunion he saw a public notice from Flinders University researcher Ben Wadham, an army veteran who leads an Australian Research Council Discovery project on institutional abuse in the Australian Defence Force. Wadham, who is about to turn the research into a book, says Cosgrove’s name came up in other reported cases of bastardisation, not just from Knox.

“I have had a number of reports across my study of Peter Cosgrove’s enthusiasm for that,” Wadham says. “He has a reputation for being pretty full on in that regard. He also has a reputation for being a very gung-ho soldier and doing things that others wouldn’t do so that might be the other side of it. Definitely a leader.”

It is always possible Cosgrove’s name is overly remembered just because he became such a prominent Australian, one who was knighted at the instigation of then Prime Minister, Tony Abbott. But David Mason-Jones, who made personal peace with Cosgrove over a phone call, denies that he was singled out, or that the tall poppy syndrome was in play.

“I believe in redemption, Peter Cosgrove has certainly redeemed himself on the national level,” says Mason-Jones. “But at class reunions, after we had the introductions, most of them would say ‘what about that bloody Cosgrove!’ There’s another side to Cosgrove, I suppose that’s what they were saying, if only people knew.”

Knox’s treatment is now with lawyer Adair Donaldson from Donaldson Law, which specialises in abuse cases with the Australian Defence Forces. The claim lodged with the Defence Force Ombudsman asserts that Knox was “psychologically and physically bullied” by a group of senior staff cadets, that Knox was told when he was sent home that nothing could be done to stop it, and that he suffered long-lasting dislocation and social effects.

Donaldson says the ADF was doing its best to atone for wrongs. “What Andrew went through should never have happened, it was brutal and it was belittling and it destroyed people psychologically,” Donaldson says. “The ADF has made statements acknowledging the horrors of the past.” He also says that Cosgrove was far from alone in a system that allowed bastardisation to flourish. “Knox saw himself as an officer going through Duntroon but that never happened. I believe our country was robbed of many great leaders (who) didn’t survive the systemic bastardisation.”

Knox says he accepted Cosgrove’s personal apology on face value but wanted more by way of acknowledgment from a man who had risen to such prominence. He would like him to stand alongside the current Chief of Defence, General Angus Campbell, to publicly denounce bullying of army recruits and give solemn undertakings that it will stop.

“It has done untold damage to many people over decades,” Knox says.

Not least to him and his family. Only last year, Knox’s wife, Jayne, was sorting through family papers and found a 1969 letter to Knox’s father from the Director-General of Recruiting, Rear Admiral Humphrey Becher.

The letter informed Ralph Knox that “top brass” at Duntroon decided they had to treat young men acceptably and that consideration was being given to paying compensation to the parents whose sons were forced out of Duntroon by bastardisation.

“If I remember, you were one of these. I strongly suggest you put in a claim,” Becher wrote. In reply, Ralph Knox said he understood how difficult it would be to eradicate bastardisation from the college but now that mistreatment had been exposed, he felt easier in his mind.

With respect to making a claim, Ralph Knox said: “I have, as you suggested, considered claiming costs, but I have decided not to revive the whole ugly business again.” He then signed off, a good military man, promising to keep these facts “confidential for all time”.