One survived a bombing in Bali, the other was the surgeon who treated him. Now, together they want to end the trauma of skin grafts

STURT footballer Julian Burton was a severely burned 2002 Bali bombing survivor. John Greenwood was the surgeon who healed him. Now, they are aiming to end the trauma of skin grafts

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE first time Julian Burton met John Greenwood he asked for a different surgeon.

Burton had just been flown in from Adelaide after being horribly injured and burned in the 2002 Bali bombings. He had been in the Sari club when terrorists blew the place up, murdering 202 people.

Somehow, Burton survived. But he received third degree burns, which extend through the skin into the fat layer, to 30 per cent of his body, requiring him to spend months in hospital, and endure multiple skin grafts and operations.

At that point Greenwood was still the relatively recently arrived head of the burns unit at the Royal Adelaide Hospital. But Burton wanted a different plastic surgeon to look after him. One he had known after a cancer scare when he was 24.

“So when I came back (from Bali) and I knew I was in trouble, I requested this plastic surgeon again,” Burton says.

“John walked in and said something along the lines of ‘thanks very much for not choosing me’.”

But Burton had no choice. He got Greenwood, an upfront, possibly eccentric Englishman, with a wide streak of dry, black humour who happens to be something of a genius in the world of burns treatment.

Asked to describe Burton as a patient he calls him a “prima donna” and reckons Burton would “shower with the door open so everybody could see his arse. It was a nightmare”.

Sitting beside him, Burton laughs and says “you can’t believe anything he says”.

But the bond between the pair — the burns’ survivor and the burns surgeon — which started in the aftermath of that Bali horror, is evident.

Now the duo believe they are on the verge of something remarkable. Sometime next year we will see “the end of the skin graft for big burns in Adelaide as far as I’m concerned”, Greenwood says.

He is talking about world-first treatment.

“This technology abolishes not only the need for the skin graft, but also provides a solution for surgeons struggling with horrific injuries, massive skin loss and huge wounds,” he says.

At the RAH alone, somewhere around 120 patients a year require a skin graft. And not just one. As with Burton, many require multiple skin grafts in the course of their recovery.

“I understand the trauma and the pain of skin grafts,” he says. “I understand the days, the weeks, the months of rehabilitation and the pain you have to go through to basically get back to your life.”

Burton and Greenwood have started a biotech company called Skin Tissue Engineering, which next year will start human trials on its patented product called Composite Cultured Skin (CCS).

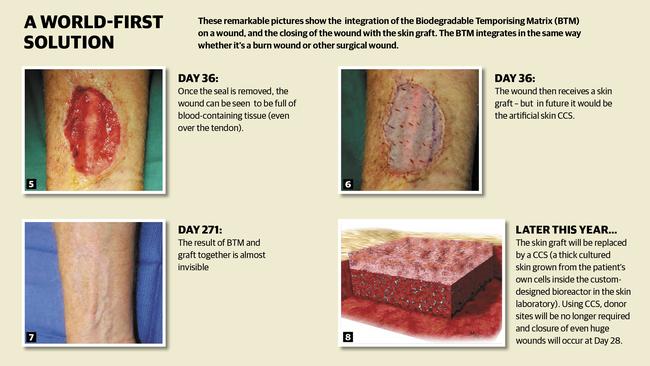

This is skin that will be grown in a specially constructed bio-reactor. It will start from a 10cm by 20cm patch taken from the body of a patient who has traditionally needed a skin graft and, over the course of 28 days, it will grow to 2.5sq m, which will give enough new skin to “cover a full human and more”, according to Greenwood.

It will revolutionise how burns patients, and anybody else who needs a skin graft, will be treated.

Greenwood says the technology is already generating “considerable excitement” in the global burns community.

Its promise has prompted Burton to close down the Julian Burton Burns Trust, which he founded 15 years ago along with Greenwood and burns nurse Sheila Kavanagh, to concentrate on this new venture.

In the wake of Bali, Burton required extensive skin grafts. He suffered third degree burns to 30 per cent of his body, mostly across his back and left arm.

Receiving a skin graft, he says, is a horrible process. The skin that is grafted on to a burns wound comes from what is euphemistically called a “donor site”. To cover Burton’s wound, Greenwood had to take an equivalent amount of skin from the non-burnt side of Burton’s back.

“Basically they graft like with a potato peeler, and they peel it off,” Burton says.

If it sounds excruciating, the reality is even worse.

“That donor site takes longer to heal and is more painful than your burnt site.”

Harvesting the skin for the graft creates another wound, another scar — and another trauma for someone already highly traumatised.

It’s been 15 years since Burton was caught up in Bali. He had been with his team- mates at the Sturt Football Club on an end-of-season trip celebrating the club’s first premiership in 26 years.

Burton was standing near a bar in the Sari Club when the bomb, which would kill player Josh Deegan and club official Bob Marshall, went off. A third South Australian, 19-year-old Angela Golotta, also perished.

The blast knocked Burton unconscious and when he came to he was trapped under pylons and the building was ablaze.

“You wish for no one to see what terrorism looks like. It’s a bloodbath.”

He is still not sure exactly how he escaped.

“I was burning, I could feel it. I could see what was in front of me and I could see people who had lost their life, so it is very vivid and it will never go away.”

Burton was evacuated, first to Darwin, then home to Adelaide where he met Greenwood.

All these years later, while the memories are still vivid, the physical scars are fading.

Burton is not afraid to discuss his recollection of Bali but is cautious in as much as he is worried that talking about his own good fortune in surviving is “disrespectful” to those who died.

The fact that he did make it out alive he puts down to being “lucky” and nothing more. He knows he could easily have died.

“There are potentially 202 families around the world that wake up every day having lost their son, or daughter, or mother or father or a loved one,” Burton says. “Whereas I wake up every day, I have a beautiful wife, with four beautiful children and I continue on with my life.”

The mental scars are still there as well. Loud noises can still shock him, and the all-too-frequent terrorist attacks reported in the media also serve as a reminder.

“There is always flashbacks,” he says. “When I see terrorist attacks on TV, I have a lot of empathy and a lot of compassion for the families.

“It’s really sad that innocent good people, either their life is taken away or their life is changed completely because of an evil act.” Before Bali, Burton was a Phys-Ed teacher at Woodcroft College. His decision to move into the charity, he says, was not motivated by Bali, but by the kindness and care shown to him by the doctors and nurses during his recovery.

Despite his view that he was “lucky”, the recovery process was, at times, traumatic and left him an “emotional wreck”.

“When you get badly burned you have to learn to walk again, you have to learn to get back to normality. You have to learn how to drive again, sit in a car again, have a shower again, go to the toilet again.

“When you suffer a major life threatening burn you are disfigured, your body is different and you have to have the emotional and physical strength to get back to that (your life),” he says.

Burton did return to both teaching and the footy field, but it was the Burns Trust that was to be his driving force after Bali.

The idea for the Burns Trust started when Burton decided he wanted to donate some DVDs and equipment to the unit as a way of saying thank you.

Greenwood told him to keep his money but suggested they put their heads together and come up with a more comprehensive fundraising method.

The doctor thought Burton’s profile and status as a survivor would be a good rallying point for a burns charity.

Initially, the Trust was to raise money for the unit at the RAH, but Burton soon thought that was too narrow a brief and it was decided to take it national.

At the time there was no other national not-for-profit burns organisation in Australia. This is despite the severity and extent of burn injury in Australia.

A 2013-14 report by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare found in that year there were 5430 burns cases that required a hospital stay, and 48 deaths.

It also found the highest proportion of those burnt were under the age of four. And within that age group, the main cause of the injury was exposure to a “controlled fire”.

Since it started, the Trust has raised more than $17 million, run prevention programs for 225,000 school children, run burns first aid programs, provided money to hospitals to improve facilities across the country, and donated money to families and communities affected by tragedies such as the Black Saturday and Pinery bushfires.

Burton is currently talking to organisations such as Kidsafe and the Australia and New Zealand Burn Association about continuing some of the Trust’s programs. A big wind-up event will also be held next year and all surplus funds given to other organisations.

Burton has no regrets about the decision.

“It was the right decision for the burns community, it was the right decision for the Burns Trust and, thirdly, it is the right decision for me.”

Greenwood’s drive to end the need for skin grafts started in 2004. He had trained as a doctor at the University of Manchester in England. After gaining his medical degree he started as a plastic surgery registrar in 1996. He would end in a paediatric burns unit in Manchester and found he had an “empathy” with the kids there.

In 2001, Greenwood was headhunted by the Royal Adelaide Hospital who wanted him as the first director of its burns unit.

He had never been to Adelaide before but decided to take an “enormous punt”.

“The quality of life is better, food is better, climate is better, schools are better. You have to be a bit daft to turn it down,” he says.

Greenwood arrived in Adelaide with his family at the end of 2001. Bali would happen in November 2002 and he treated 67 patients in the immediate aftermath of the bombing.

But it was a couple of years later that he first started to seriously think about how possible it would be to replace the skin graft.

Skin grafts had been around for 150 years and were regarded as an essentially successful way to treat the problem of covering burns and other wounds.

Greenwood, though, was perturbed by the death of some of his patients — “young patients, with decent-sized burns, who died and there was no reason for them to die that I could see”.

He started cataloguing injuries. He wrote protocols on how treatments should be carried out on patients with different types of injuries. The protocol on non-survivable injuries naturally troubled him.

He pegged “non-survivable” as 80 per cent “full thickness” burn plus injuries to lower airways. But, as he says, anyone “with a shred of humanity” will keep looking for answers to change the equation.

Greenwood thought if he could somehow deal with the burns side of the ledger then there were ways of keeping someone alive.

One of the biggest problems with a patient with an 80 per cent burn is that there is no donor site. There is no place to find the skin for the graft.

Even in those patients who have “donor sites” available, there can be problems with infection, delayed healing and poor scarring. “Even without problems, donor site wounds are excruciatingly painful,” he says.

“In a big burn situation, where donor sites are scarce, I can’t keep going back to the same small donor site over and over,” Greenwood says. “The second time I want to take a graft from it, the donor site is ‘thinner’ and if I keep going back to it, sooner or later the donor site itself will need a skin graft to heal.” The solution is a two-stage process.

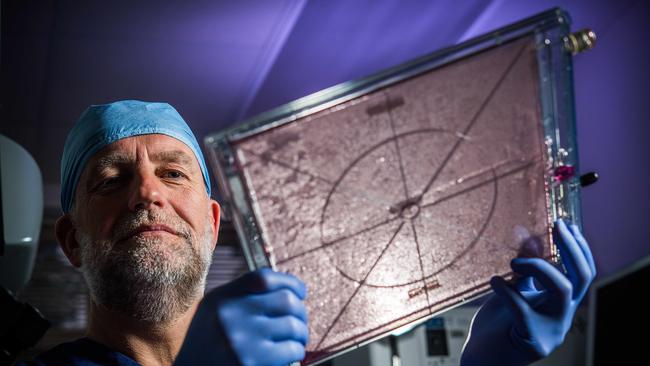

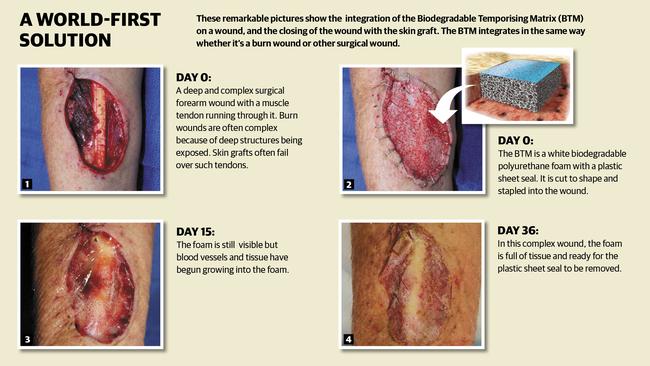

With a company called Polynovo, and its NovoSorb technology, he developed what is called a Biodegradable Temporising Matrix (BTM), which improves the wound, resisting contraction and discouraging infection. A biodegradable polymer foam is placed in the wound and acts as a “scaffold” so the patient’s own tissue and blood vessels grow into it and create connective tissue. It was first tried in mice, sheep and then pigs in 2010. The first human trials started in 2012. Now the method is being trialled in all adult major burn centres in Victoria, NSW and Queensland as well as in the United States. South Africa will start using the BTM soon.

When it is combined with the Composite Cultured Skin, which is the second stage, Greenwood says the pain and suffering caused by donor sites will be a thing of the past, and those burn victims with extensive skin loss and no donor sites will have a treatment to save life and improve outcome. To create the CCS, Greenwood has had to invent a bio-reactor to encourage the skin to grow in 40 pieces 25cm x 25cm. The polyurethane foam is initially seeded with dermal cells and submerged in the bio-reactor in a specific fluid, under specific conditions. Once the dermis has been created, epidermal cells are added to give cultured skin with both layers found in normal skin.

Of course, just by removing the donor site, scarring will automatically be reduced. “So instead of leaving patients looking like a big lizard you actually get a very flat result, it is very elastic, very soft,” Greenwood says.

Funding was provided by TechinSA, the old BioinnovationSA, and the Lifetime Support Authority. But in the world where the cost of medical trials can run into the billions, it was small beer.

“We have managed to abolish, pretty much the skin graft for $1.5 million, which is a bit ridiculous,” Greenwood says.

The benefits are not just the physical improvements that ending skin grafts will produce. There is the mental side as well.

What it should mean is fewer operations, less time in hospital, a greater chance of a full recovery, and the ability to get back to life and work much quicker.

It is estimated a life-threatening burn injury to an adult costs between $750,000 and $1m and, for a child, more than $1m. That doesn’t include the cost of rehabilitation and recovery, or the loss of work.

“Instead of being three months in hospital, you might only be one month in hospital,” Burton says.

“You will still have pain and trauma, don’t get me wrong; but your recovery and your rehabilitation will be 50 per cent less.”

Burton and Greenwood are confident they are on the verge of something remarkable. And not only in skin grafts. They believe the technology used in the BTM process could also help treat Type 1 diabetes by replacing the pancreas to produce insulin.

But given the links of both Burton and Greenwood to the trauma of burns patients, it is the hope that they can eliminate a lot of that suffering that is really driving them.

“One day, if I’m 85 sitting in a rocking chair looking back on it, if we could change the way burns are treated globally and if we can do that from here in South Australia that would be phenomenal,” Burton says.

“He is the visionary, I am a burns patient. It’s a bit of a love match that really works.”