Noni Hazlehurst: Ageism, Play School and not being perfect

Legendary actor and presenter Noni Hazlehurst says ageism is rife in Australia, and it’s time we all worked together to bring it to an end.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It took Noni Hazlehurst a long time to realise she was trying to reach the top of a mountain that nobody could climb. “I was brought up to believe there was such a thing as perfection,” the 67-year-old actor and presenter says. “And I now understand that nothing is ever perfect. I was brought up to believe I wasn’t quite up to scratch. And one of the joys of getting older is that you don’t care.”

Actually, Hazlehurst does care, about many things: a fair go for women, less screen time for kids, the divisive state of politics, social media’s nasty side, the need for more compassion – and ageist thinking.

What the AFI award-winning film, stage and TV actor and Play School stalwart means is that she’s more at peace with herself these days. Living alone in the Gold Coast hinterland, she’s taken heed of advice she used to share with the nation’s preschoolers.

“Play School gave me the mantra: practice makes progress,” she says. “It’s actually impossible to be perfect. And I love, you know, Japanese pottery (kintsugi), that when it’s broken, it’s repaired with the cracks evident because that’s a sign of character and age and use.”

The value of the old, even when there are signs of wear and the odd crack, is a lesson Hazlehurst wants all Australians to learn. She says she’s on a mission to change the way we think about ageing, and later this month is hosting the ageing episode of new SBS documentary series What Does Australia Really Think About…

Ageism is rife, she says, and it’s wrong. The elderly feel isolated, devalued, and their mental – and perhaps financial – health suffers. The young miss out on stories, wisdom, perspective and valuable lessons. And everyone misses an opportunity to connect with empathy.

“I think it’s important to understand that you are not your age,” she says. “Your body might be your age, but you are not your age. And that’s where making judgments about people based on their age is a one-way ticket to nowhere, because you’re not connecting with people, you’re connecting with a cliché – and that’s pretty shallow.”

The program argues ageism is more tolerated than other “isms”. Jokes and references to someone’s age are more likely to be acceptable than those concerned with their sexuality, gender or race.

But ageism, Hazlehurst says, is the one “ism” that everybody, if they live long enough, is at risk of facing.

And the ranks of the aged are growing. In the next decade, forecasters say there will be a 30 per cent increase in people of retirement age. Longer term, the historically high 16 per cent of people now aged 65 or over will, in 35 years, be almost a quarter of the population.

Yet, as the recent aged-care royal commission showed, society’s treatment of many elderly people has been shockingly neglectful, with an “out of sight, out of mind” mentality.

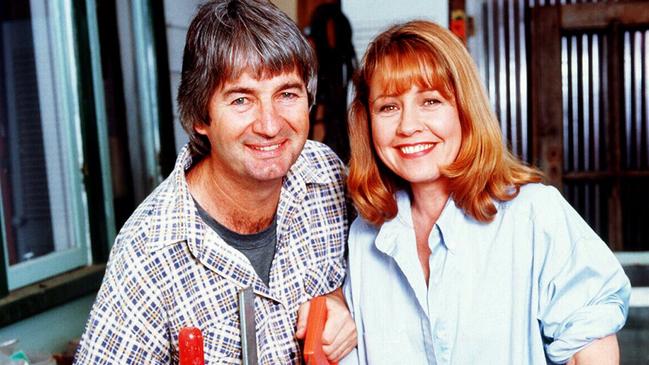

Hazlehurst thinks she can reach across generations. A baby boomer, her career roles range from playing a single mum in 1982’s Monkey Grip to a dementia-stricken pensioner in 2021’s June Again, 24 years on Play School and a decade hosting Better Homes and Gardens from 1995.

And she is not afraid to say her piece. When she became just the second woman in 32 years to be inducted into the Logie Hall of Fame in 2016, she gave the industry both barrels for its failure to support women. Last year she accused the federal government of abandoning the arts industry during Covid.

The years may have added a few wrinkles, but they have also honed her skills at making people feel something. At one point in the SBS program, a hidden camera captures an elderly couple shopping for a smartphone being told by a young salesman: “If I show you how this one works, you will just forget it.”

They are devastated. Hazlehurst, watching the tape later, sheds a tear and mutters, “I hate people sometimes”. “I was just so angry,” she says. “But underneath all anger is pain ... and the pain is about the lack of recognition of our fellow human beings. It’s just pathetic.”

Contrast that moment, she says, with the happiness the couple enjoys after being treated decently by a different young salesman.

“You could see how rejuvenated they were when they came away from the young guy who was sympathetic to them and treated them like actual people, rather than decrepit old has-beens,” she says. “They’d been validated, and not ignored and marginalised. It was so sad to see how little it takes to make someone feel that they matter.”

Respect is one of the keys, she says. But in a youth-centric culture fostered by unrealistic TV shows where “all the women are blonde and under 30, wearing hot pink”, that’s not encouraged.

She rejects the push to look younger. “I’ve earned every wrinkle,” she says, insisting she’s never been interested in surgical interventions. “I prefer to reflect real people.”

Older age brings a realisation of “who you are”, she says. “And there’s no point pretending you’re otherwise, but unfortunately a lot of us do feel we have to keep that pretence up. (For me) that’s not a thing anymore, that I have to live up to a certain expectation of how I should look. And so I can just be who I am, warts and all. That’s incredibly liberating.”

Hazlehurst reckons she was fated to act. One great-grandfather was a world-famous aerial acrobat, her grandfather was also an acrobat, and her parents met when they were performing on the same bill in vaudeville in England before migrating to Australia. She recalls how in her first role, aged three, as Little Miss Muffet, she was so terrified of the spider she ran off.

At high school she won a Victorian award for her Shylock, “with a steel-wool beard and a bad accent” in Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. The following year, 1971, she left for Adelaide’s Flinders University, where she studied acting with the likes of late Angels singer Doc Neeson and husband and wife team Scott Hicks and Kerry Heysen, who made the Oscar-winning film Shine.

It was early in the Dunstan decade, and Hazlehurst recalls a role in the first play at the Space Theatre at the new Festival Centre. She knew acting wouldn’t be lucrative, but she was sure she’d be a success. When her lecturer told the class only two of them would make it in the industry, she says she looked around and thought to herself: “I wonder who the other one is?”

Her first long-running TV role in the raunchy The Box in 1974 was followed by other popular serial dramas of the time like The Sullivans and Division 4. By 1985 she’d won two lead actor AFI awards for films Monkey Grip and Fran and over following years continued to work in film and TV, preferring to stay in Australia.

“I think Play School was my favourite role,” she says of her 1978-2001 stint as one of the presenters on the show. “It taught me so much about communication, but also … what an important time preschool years are for children. That preschool period is absolutely crucial in the development of the human being and it was a privilege to do that for 24 years.

“And it was quite profound to understand how hard the world is for young children to understand if they haven’t got a caring adult to contextualise it for them. And the beauty of Play School is that it was simple, easy-to-understand everyday concepts three- or four-year-olds could deal with and follow.”

Children need adult interaction, she says, and giving them screens for amusement means fewer interactions with grandparents because ordinary people can’t compete with the colour and glamour of what’s on those devices.

“There’s not enough peace for young children, especially in the city,” she says. “I don’t see it as coincidental that there’s been a concomitant rise in things like ADHD and kids not being able to focus, and kids’ depression and anxiety. If you’re a powerless child, the world must be a terrifying place.”

Hazlehurst is hoping for grandchildren herself, from her two sons with second husband John Jarratt, William, who lives in Nashville, and Charlie in Melbourne.

For the moment, she is facing her advancing years mostly alone. She’s been twice married but is content by herself.

“This is an important time for me to be alone,” she says. “I have great friends, live in a relatively safe part of the world, so I’m not dissatisfied on any level.”

But while life amid Mt Tamborine’s rainforests sounds idyllic, her family home will be too big for one person to manage, she says. Her plan is to one day live close to one of her sons – if not on the same block. Maybe they’ll organise a shipping container, she jokes.

“I think you do get to a point where you have to acknowledge that you need people around you,” she says. “Because you do get more infirm as you get older, and you have to factor that in. And also, being alone, I think, is not conducive to healthy, functioning old age.

“I think it’s important that you know, that you do have contact with people and certainly Covid has made it much harder for particularly old older people to have any kind of interaction with their fellow human beings. I don’t think I’ve had a proper hug for 18 months.”

Hazlehurst thinks women are starting to get a fairer go in her industry, but says, as a woman ages, the roles become fewer and more limited. “When you’re in your 20s and 30s, and even early 40s, you get a full character description and it’s more likely to be a leading character,” she says. “But now that I’m in my 60s, I get offered roles anything up to sort of 80-year-olds, and they tend to just be a very brief character description of mum, typical mum, typical grandma.”

She says there are plenty of characters she could play, regardless of age, and points to Sir Ian McKellen playing Hamlet in London at 82.

“Look, I think it’s disheartening that most of the roles, or all the women tend to be, you know, suffering from something on their deathbed,” she says.

Still, the critics say she does them well. Her performances in the successful TV series The End, an intergenerational “dark comedy” about ageing, and the Australian film June Again, in which she plays a woman with Alzheimer’s disease who regains – briefly – her memory, received enthusiastic reviews.

Likewise, a reviewer described Hazlehurst’s one-woman play Mother, written for her by Daniel Keene, as the performance of her life. She again played an older woman, but one you would cross the street to avoid, destitute and homeless.

She wants to make the audience walk in the woman’s shoes, because “if you make a judgment about someone based on how they look, you’re never going to know them as a human being”.

That role echoes one of the most powerful moments in the SBS documentary, when it reveals to a roomful of well-dressed women just how many are statistically just a slip or two away from poverty and homelessness.

While one of the program’s surveys found 53 per cent of people under 40 thought that the biggest benefit older Australians could provide to society was to “pass along their resources”, in reality many are poor. About 400,000 older women are deemed at high risk of having no home of their own.

Hazlehurst thinks that’s symbolic of many people. “We’re all pretending that we’re fine. You know … we’re so conditioned to believe that we have to appear to be coping all the time. And I don’t know anyone who is not struggling on some level. If you talk to people, everyone has some cross to bear.”

Hazlehurst sounds passionate, but she insists she can take or leave her work. “I don’t place a lot of importance on my career,” she says.

She’s not been in it for the attention, she insists, only for the chance to be a storyteller and communicate.

“And so I look for opportunities to do that, that I think will be of value to some people,” she says.

“And I think I could let the acting go tomorrow if I couldn’t find a story that I thought was worth telling. It wouldn’t bother me. I’d rather knit jumpers for a living than be part of promulgating ideas that I think are unhelpful or pointless.”

If it’s possible that Covid provided any positives, she says one has been some increase in empathy. We’re not in the same boat, she says, but we are in the same ocean. People, when they ask how you are, are going to really mean it, she thinks, because they’re not coping either.

For those who might classify her as a bleeding heart or “woke” – she’s not bothered.

“I’d rather be woke than asleep,” she says. “If woke means being alert to injustice and inequality, then I’ll put my hand up for being woke any day of the week.”

It’s just another example of the danger of making “surface judgments” about people. “And it’s that kind of kindergarten playground mentality that everything I say is 100 per cent right, and everything you say is 100 per cent wrong. And that’s just not possible.”

Hazlehurst insists she is not looking through rose-coloured glasses at the past. “I got locked in dressing rooms with people I didn’t want to get locked in with and had to scream and yell – and you know, turn up in certain auditions wearing skimpy stuff when I was very young,” she says. “But that was normal then. You look at some of the stuff that we watched through the prism of today’s consciousness and you’re appalled, but that was just normal.”

Many other things also seem different looking back. In an interview, Jarratt once said that Hazlehurst judged herself too harshly. “She comes from a family where she was dux of the school with 98 per cent and her father asked her where the other 2 per cent was,” he said in 1998. “I spend my time trying to convince her she’s extremely gifted, extremely talented, an amazing human being ... but she’s never talented enough, good-looking enough, tall enough.”

That’s the hunt for perfection Hazlehurst says she’s learned to accept is not possible. At the end of our interview she begins to reflect on influences in her life, but is suddenly seized by the memory of watching a documentary on late Melbourne artist Mirka Mora.

“She was about 80-something, and she was still incredibly flirtatious and little girly and very funny,” Hazlehurst says. “They showed pictures of her when she was young, and she was staggeringly beautiful. And they said, ‘do you have any regrets?’ And she said: ‘Yes, that I didn’t know I was beautiful when I was beautiful.’

“That just hit me; that was like a sucker punch to me. Because, as I tell my daughters-in-law all the time, you will never be as young as you are today.”

What Does Australia Really Think About… is on SBS from August 18 at 8.30pm, with Hazlehurst’s ageing episode on August 25.