Why has Mintabie been left to rot? Traditional owners, locals demand answers

Mintabie was once thriving, flowing with booze, drugs, cash and some of the world’s best opals. Now it’s a smashed-up ghost town left to rot. Why? Locals and Traditional Owners demand a path forward?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

TRADITIONAL Owners of the Outback opal Mining town Mintabie say they are “frustrated” and “angry” at the lack of progress made with the town since its government-forced closure nearly three years ago.

The town, about 1300km from Adelaide on the outskirts of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, was closed in January 2020 on the back of a damning government-commissioned report that cited “serious law and order issues” and identified Mintabie as a supply point for drugs and alcohol into the lands.

The Mintabie Review Panel, which handed down its report to the Labor government in 2018, recommended the town be immediately closed and handed back to Traditional Owners so the land could be rejuvenated after four decades of damaging open-cut opal mining.

The town’s residents launched Federal Court legal action, citing discrimination, and were granted an extension until the beginning of 2020, but still forced to leave.

Now, the Traditional Owners, Anangu, who supported the town’s closure, say they have been left “in the dark” since the decision was made. “Our frustration is the clean-up and the nothing happening out there when government made the decision to do what they were going to do which was close the township,” Karina Lester, a Traditional Owner at Walatina Station said.

Ms Lester has lived at Walatina on and off for 30 years after her activist father Yami Lester, who was blinded by British nuclear testing at Emu Field as a boy, took over the station’s lease in the 1990s.

“We want the clean-up to be done and … something where Anangu can feel that they can contribute to see that community rehabilitating or that Country or that place that has cultural significance to us slowly get back to healing and back to itself,” she said. “But currently, the way that it is now, Anangu don’t want it given back to us.”

Ms Lester sat on the Mintabie Review Panel and supported its recommendation to close the town, a decision she stands by now, but said government talks with Traditional Owners stopped once the town was closed.

“People from Indulkana and Mimili … they were all pretty not clear about what’s the process … and then all of a sudden the government made that decision and things were sort of all happening then out of their control,” she said.

“We’re sort of waiting on what government’s doing or thinking or what they’re going to do.

“It kind of got out of our hands.”

Ms Lester said closing the town had not stemmed the flow of drugs and alcohol into the APY Lands despite the spread of illicit substances into vulnerable communities being a key motivation of the review panel’s decision.

Kevin Davies scuffs his boots through the piles of ashes on the Mintabie Hotel floor, walking through the building’s skeleton without a word.

He pauses a moment, drags on his cigarette, lowers his arm and exhales. Surveys the ruins and reminisces. By the time he rejoins the present, his smoke is out.

He flicks his lighter once, twice, and drags again. What he sees still doesn’t seem real.

Ceiling tiles and ash cover the floor, rusted and warped steel hangs menacingly from what’s left of the roof.

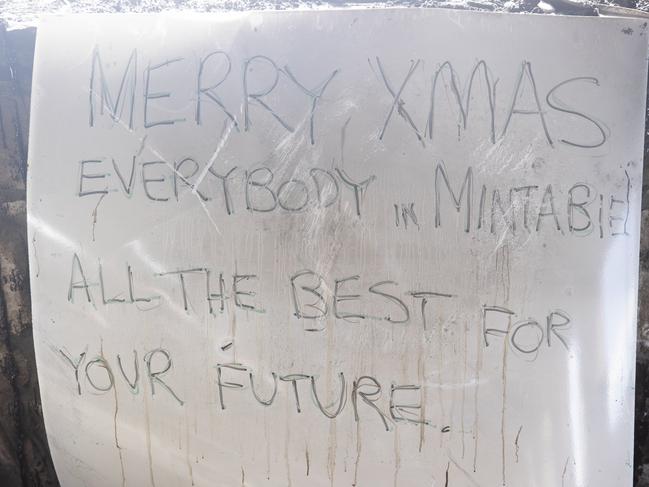

In the corner of the pub, below where the TV was perched broadcasting every grand final and Test match, a message on a whiteboard sums it up: MERRY XMAS EVERYBODY IN MINTABIE GOOD LUCK WITH YOUR FUTURE.

It’s not the first time Davies has seen his long-time watering hole since it burnt down last year, but the words still struggle to leave his moustached lips. He stands a moment longer, still without a word, and trudges on.

“All this would be packed with people,” he manages a little later, pointing across the room.

The sign, left over from the last Christmas held in the South Australian mining town before its closure almost three years ago, is a reminder for Davies of all the occasions celebrated in the stonewalled building: Christmas, Easter, Anzac Day, the birthdays of many of the 30 or so residents left in town by the end. The pub hosted them all.

The town had been long abandoned when the hotel, hand-built by locals in the 1980s, was destroyed last year.

A couple of miners still digging in the adjacent opal field saw the smoke and headed into town but by the time they got there the building had already been swallowed by flames.

Davies heard the news a few days later and returned to his home of 18 years to find the pub ruined. “I was just f**king gutted,” he says.

“When I come around the corner I looked at it … I wanted to turn around and go back.”

Of all the people forced out of the town after a damning government-commissioned report, Davies appears to harbour the most anger.

Like many who made the speck of a town on the outskirts of the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands home, once Davies had set foot in the plentiful dirt at Mintabie, he never left.

There’s something about the town, almost all the former residents say … it gets under your skin. It pulls you in and doesn’t let go.

A short drive from the ruins of the pub, Davies shows us what remains of his former home, burnt down before the town’s closure, while he was away.

Mintabie is a small place and Davies says he has confronted the person he suspects of lighting the fire a couple of times but he says no charges have been laid. Nor have they over the pub fire.

The hurt is visible in the 67-year-old’s face when he talks about the loss of his home, but it still didn’t dampen his view of the town.

Rather than leave, he shacked up in another part of town and went about his days looking for the big find with no intention of leaving.

Ultimately, he wouldn’t have a say in it.

When the review of Mintabie’s lease arrangement began in 2017,most residents didn’t think much of it.

They knew their home was subject to an agreement between the state government and the Traditional Owners of the APY Lands – a rolling agreement in place since the 1980s – and they knew their town had been on a downward spiral for some years before the review, but in this part of the world, dysfunction had become the norm.

And what was happening certainly wasn’t anything the town full of larrikins and chequered pasts hadn’t seen before.

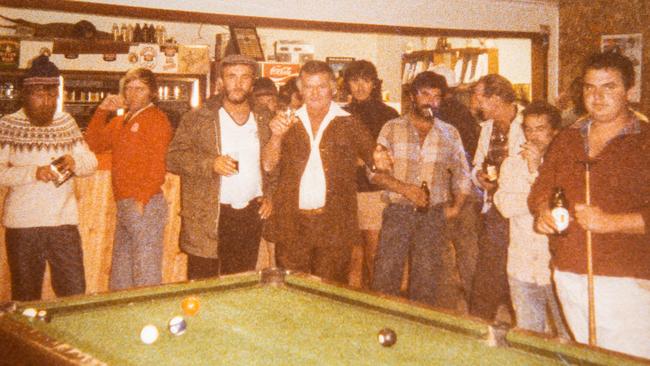

Mintabie in the 1980s and ’90s was as wild west as outback South Australia got; brawls, guns, murder, dynamite and two-up games with tens of thousands of dollars at stake.

At least, that’s how the stories go.

Chartered planes filled with Malaysian and Chinese opal buyers roared into the silent desert night at all hours, landing on the town’s dirt airstrip ready to part with thousands of dollars for the prized black opal that literally put Mintabie on the map.

Cigarettes were lit with $100 notes. The nappies of youngsters waddling around the pub, while their parents enjoyed the spoils of their prospecting, were filled with $50 notes as they crawled by.

Once there was a truckload of prostitutes brought in by a miner who had struck colour and made a fortune, according to a former resident’s anecdote. Another says it was a plane load, and the fortune was soon burnt through.

What is agreed on by all though, is that Mintabie was a wild place, founded as an offshoot of the original frontier mining town Coober Pedy a few hours south.

Word has it that one of the first miners to set up shop in Mintabie was a Croatian migrant – a “hard nut” too out of control even for a town such as Coober Pedy back then.

“Can you imagine the people that were here 45 years ago?” says Jamie Wilson, an opal miner who has dug at Mintabie for almost 20 years. “They were people that had to leave their country otherwise they would have been killed over there. They were hard-working men and they drank a lot of piss and they didn’t put up with any s**t.”

Wilson shares one tale, heard second-hand from back in the day, of a man being shot by a miner over a dispute, before he was tied to a car and dragged along the main street. He reckons the miner’s legal fees were covered by a mate and he was cleared of any wrongdoing.

It’s not the only yarn that a former resident shares about things getting hairy in Mintabie.

Another who has mined at the town on and off since the early 1980s says he has lost count of how many murders he’s been told about over the years.

There are plenty of holes in the ground and plenty of people who were in town one day and gone the next without a trace, he says.

Milan Rako, the “hard nut” exiled from Coober Pedy in the 1970s, was one of the lifers who fell so deeply in love with Mintabie that it became home immediately.

“He wouldn’t have left,” Wilson says. “He would rather have died than leave.”

And in 2018, he did. The next day, Wilson says, came the news that the town would be closed. He’s not big on coincidences.

On January 20, 2017, then-prime minister Malcolm Turnbull wrote to then-premier Jay Weatherill offering his support to terminate the Mintabie lease.

The town’s fate was effectively sealed.

Less than six months after Turnbull’s letter, the Mintabie Review Panel began its work.

According to its 53-page report, handed down on January 3, 2018, community members had raised serious concerns about a number of issues, including illegal activity in the town including drug dealing and the distribution of alcohol into the APY Lands. However, it also noted many Anangu people were sympathetic to older residents’ wishes to remain in the town.

Mintabie miners reckon the town’s opal is some of the best, if not the best, in the country.

It’s better than Coober Pedy opal, they say, and stands up against any of the famed black opal coming out of the ground in Lightning Ridge in NSW.

Coober Pedy miners say the opal coming from their patch is just as good as any.

“I think of Mintabie as diamonds and Coober Pedy as cubic zirconia,” Wilson says as he empties a small lunch box of Mintabie opal on to the bonnet of his ute just outside Coober Pedy. The flashes of blue, green and red glow against his rough hands in the overcast morning light. He fossicks through the pile, worth somewhere around $7000.

It sounds like a fair stack of cash to be sitting on the hood of a Nissan Navara but it’s taken the best part of a fortnight digging at Mintabie to pull that small stash from the ground.

By the time he pays the wages of his two workers and accounts for overheads, Wilson will barely make a profit.

Like Davies and other Mintabie residents, Wilson naturally relocated to Coober Pedy – the “opal capital of the world” – after the town’s closure.

Before, Wilson effectively worked in his backyard. Now he makes the four-hour commute between the two towns, and then to Adelaide and back to sell the stones, the cost of fuel eating into his already slim takings.

That’s why he had to go back on the dole.

“With most people, it costs them money to go mine there,” he says.

Why does he go back?

“It’s as bad as a f**king ice addiction, man,” he says. “I’m tellin’ ya … I wouldn’t wish that upon anyone.”

“It sings to ya,” adds Dylan Brown, who has worked with Wilson for seven years.

Wilson calls it an addiction, others call it the “opal bug”.

And when the bug bites, it bites hard. Another miner calls it “the rot”.

For him “the rot” set in the second he set foot in the town in the early 1990s.

“I wanted somewhere to go and my brother-in-law said, go to Mintabie,” he says. “I hired a plane and flew up there and as soon as I landed I just fell in love with the joint.”

He asked not to be named so he could keep a “low profile”; it’s got to do with a dispute over a large opal find a few years back.

The review panel saw three clear options for Mintabie’s future:keep both the town and the opal field open; close the town but keep the opal field open; and, what would be its overwhelming recommendation, close both.

Of the issues raised in the report, the panel’s recommendations came down to a few key factors. At the forefront was the town’s “serious law and order issues”, which the report said included an arson attack that destroyed a home (it’s unclear if this is the fire that involved Davies’ home), a woman being “imprisoned” in her home and sexually assaulted, and drug dealing.

Anangu people in Indulkana and Mimili, towns north of Mintabie, told the review panel that the town was a supply point for drugs and alcohol into the APY Lands.

Three separate organisations, the Nganampa Health Council, Money Mob Talkabout – a financial counselling service – and the Ngaanyatjarra Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (NPY) Women’s Council also considered Mintabie to be the supply point for drugs and alcohol into the lands.

Former Mintabie residents don’t dispute the presence of drugs – mostly cannabis, according to the miners, but there is talk that Mintabie was used as a gateway for harder substances like methamphetamines – in the mining town, but they do say the problem was blown out of proportion.

“The review was made to blacken our name,” Davies says.

“The town was closed on bullshit,” Wilson adds.

Another key issue raised was the Mintabie Precious Stones Field (MPSF) – the opal-rich ground responsible for the tales of fortune and misfortune in town.

The report said miners in town had labelled the field “depleted” and proposed a new field be opened, with the bill for new access roads to be footed by the state government.

An estimate provided to the review panel by the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) reported about eight of the 213sq km of the field had been mined in the almost 40 years since it was first proclaimed. It was estimated about 55sq km of “highly potential opal-bearing ground” remained, not taking into account the area outside the town residents petitioned the government to fund exploration of.

The figures provided by the DPC, based on a formula by senior department geologist Jack Townsend paint a picture of life in Mintabie during the opal-rich ’80s and ’90s.

From 1985 onwards, it becomes clear much more money was coming out of the ground than being put in. In that year alone, $15.56m of opal was mined for an investment of $9.35m; 295 miners called the town home then.

Year on year after that, the opal – and the money – flowed.

“There’s lots of stories here with millions of dollars,” say a miner, who was forced to move to Coober Pedy.

“People were lighting their cigarettes with $100 notes … that’s the story of opal,” he says.

By 1988, 775 miners – former residents say it felt more like 2000 – had landed in the town, shifting dirt in the hope of unearthing their retirement fund deep below the surface. They pulled $39m from the ground after spending $18.6m, with miners in Mintabie outnumbering those in Coober Pedy by 150.

Then the numbers decline but those who stayed continued to reap the rewards: $31.5m in 1989 between 600 miners; $22.6m in 1990 between 454; and $18.2m in 1993 between 376.

Not everyone got a share though.

“I put half a million dollars into the ground and I got nothing, nothing,” says the miner who shared the $100 cigarette story. “F**k all. Five thousand here, $30,000 there.”

By the time Davies arrived at the turn of the century, the number of miners had dwindled to fewer than 150 for $7.75m of opal.

A decade later in 2011, only 40 miners were still in Mintabie. It’s from this point, the review panel says, the town went downhill.

When the panel started its work in 2017, the cost of mining in Mintabie over the previous five years had outweighed production every year. In one year, costs outweighed opal by as much as $3m. Overall, between 1978 and 2016, $411.13m of raw opal was pulled out of the ground.

Many of those forced out believe there is much more waiting to be found, a view that seems to be supported by a separate evaluation provided to the review panel by Laszlo Fernando Katona, the principal geoscientist at the Geological Survey of South Australia.

He said less than 2sq km of the Mintabie Precious Stones Field had been intensively mined and the $411m mined in the area represented less than 10 per cent of the opal at Mintabie.

He put the retail value of the rest of the area at somewhere just south of $2.5b.

At the same level it had been explored since 1978, he said, a 20sq km patch would support mining for the next 400 years. In the end, though, his opinion did little to stop the town’s death.

“Should the township be closed but the MPSF remain open, the continued access to the area could negate the positive outcomes achieved through the closure of the township,” the review panel’s report said. “As such, the closure of the MPSF should be considered as a priority.”

The field, however, remains open, with a lease agreement in place until 2027. But with only a couple of miners such as Wilson prepared to make the commute, many believe it won’t last more than a year.

Only 20 or so kilometres away from the opal field, Karina Lester sits beside Ngintaka waterhole at Walatina Station, a 5500sq km property with a leased area that covers the Mintabie township.

It’s a significant place in her culture and her home, where her family has been since the early ’90s when her activist father Yami Lester – blinded as a boy by the British nuclear testing at Emu Field – took over the station’s lease.

“When we landed, it was pumping,” Lester says of Mintabie in its heyday. “It was a thriving little community in the early ’90s.”

She has come and gone over the years, living between Walatina and Adelaide, but her connection to this land runs deep.

Long before Mintabie was proclaimed by the miners, the Walputi, or numbats, called that sacred land home. The Dreaming story goes that while singing a traditional song, a Walputi man ground his nails as an instrument, Lester explains, rubbing her own fingernails together.

The nail filings fell to the ground, leaving a white powder on the surface that seeped into the Country, creating the unique milky colour of Mintabie opal.

The waterhole Lester sits cross-legged beside has its own story that runs as deep through the red dirt of the APY Lands.

Of the Mintabie Review Panel’s 14 recommendations, the first was that the town be closed “as soon as practicable” and management of the land be handed back to the APY.

Lester, who sat on the panel with her late sister Rose, is one Traditional Owner who has been left asking questions about the government’s handling of the closure almost three years on.

Once the call to close Mintabie was made, Lester says, talks with Traditional Owners of the area stopped.

“People from Indulkana and Mimili … they were all pretty not clear about what’s the process … and then all of a sudden the government made that decision and things were sort of all happening then out of their control,” she says.

“We’re sort of waiting on what government’s doing or thinking or what they’re going to do. It kind of got out of our hands.”

Another recommendation was that local Anangu people be employed to undertake clean-up of the town, estimated to cost about $3m, and make good of the cultural sites neglected since the town was proclaimed.

Lester says that, too, hasn’t happened.

“Our frustration is the clean-up and the nothing happening out there when government made the decision to do what they were going to do, which was close the township,” she says.

“We want the clean-up to be done and … something where Anangu can feel that they can contribute to see that community rehabilitating or that Country or that place that has cultural significance to us slowly get back to healing and back to itself. But currently, the way that it is now, Anangu don’t want it given back to us.”

As the three-year anniversary of residents’ last day in town approaches, the town is hardly a town any more. Along with what’s left of the pub, almost every home and business in town has been vandalised.

The second-hand shop’s floor is covered in piles of clothes, torn from the shelves and rifled through after being left behind in the mad rush out of town.

Lester isn’t the only Traditional Owner who’s been left frustrated and in the dark about the future of Mintabie.

Mark Campbell, another Traditional Owner of the land at Mintabie who was the deputy chairman of a subcommittee tasked with managing the town’s transition back to APY ownership, was an outspoken critic of the town ahead of its closure.

Now, his opinion has changed.

“Closing the town was a mistake,” he says.

“I thought I was saying it for a good cause and everything but then growing up and learning a few things along the way and I realised it was not a good thing in the first place.”

Like Lester, Campbell says closing Mintabie hasn’t stemmed the flow of drugs into the APY Lands. Campbell says he has copped the brunt of community anger since the town closed because of his strong stance on the issue back then. He says he was told the closure would mean housing and employment opportunities for Anangu people but instead the town has been left untouched and unhealed.

“I am disappointed and angry about the fact that it’s taking this long to get the clean-up going,” he says.

Indigenous Affairs Minister Kyam Maher, who held that portfolio when the Labor government decided to close Mintabie before it became the Liberal government’s responsibility, says despite the time that has passed since the town’s last day, handing the land back to Traditional Owners is “on the radar”.

“That is certainly something we’re looking at now that we’re back in government,” he says.

“Looking at how proper handback is effected and what it means for remediation of what’s left there.”

One thing he is sure of is the government’s decision to shut the town: “Absolutely, I think it was the correct decision to close down Mintabie.”

APY general manager Richard King said the clean-up at Mintabie was being managed by the Energy and Mining Department and that a scope of works had been agreed upon between the parties, with issuing tenders for the works the next step in the process.

King said APY was “working towards maximising Anangu employment rates” and looked forward to working with the department and state government to “progress remediation of Mintabie”.

Campbell puts a lot of the blame on himself for Mintabie’s closure – even though he was not a member of the review panel – and he wants to make good on the wrong he feels he did people by now pushing for the town to be reopened.

The residents in Mintabie didn’t go down without a fight.After taking their case to the Federal Court on discrimination grounds, they were granted an extension to stay until the beginning of 2020 but still had to go.

Their deadline of June 30, 2019 was extended until the end of the year, before a 50C-plus heatwave bought them a few more days.

But soon after the new year, the red dirt main street was filled with trucks, cars and residents loading up everything worth taking to relocate to wherever it was they were going to try to make their new home. Those there on the day say it was the toughest day in the town’s history.

“I’m still not well from that,” says Christine Watkinson, an opal miner who lived in Mintabie from the early 1980s until its closure. “It was 54C in the shade. It was boiling hot. My head got so burnt that I had blisters come up all over it.”

Fighting back tears she described that last day, with the looming threat of government fines for anyone not gone by the cut-off date, as “hell”.

“Everybody was crying,” she says. “It was pretty nasty actually. No water. There was no food, nowhere to sleep. Everybody was just sleeping in their cars. They were hungry, they were thirsty and they were just worn out. It was just a nightmare. It was like hell on Earth.”

Watkinson was another who landed in Mintabie when the town was barely a town and made it her forever home without blinking.

“Everybody from Mintabie still talks about Mintabie every day,” she says. “We were shafted. They were ruthless. Absolutely ruthless. There are people that have died because of moving.”

In Mintabie, Christine says, she owned four houses and now she lives in somebody else’s.

“I left behind four houses and I now pay $1000 a month for rent,” she says, surrounded by boxes of possessions brought with her to Coober Pedy.

Like most of the former residents, she says the relocation money she received from the government wasn’t enough to cover her moving costs. Most long-term residents walked out of the town with around $30,000 in their pockets. Others, with businesses, walked out with substantially more.

Whoever left with what, they all left hurt.

“It seems like yesterday and yet it seems like a million years ago,” Watkinson says.

She hasn’t been back since. ■