Mr Clicketty Cane: Peter Combe is still as popular as ever

Peter Combe wrote the soundtrack to many of our (early) childhoods. Now in his 70s, he’s not slowing down – so what’s the secret to his incredible success?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

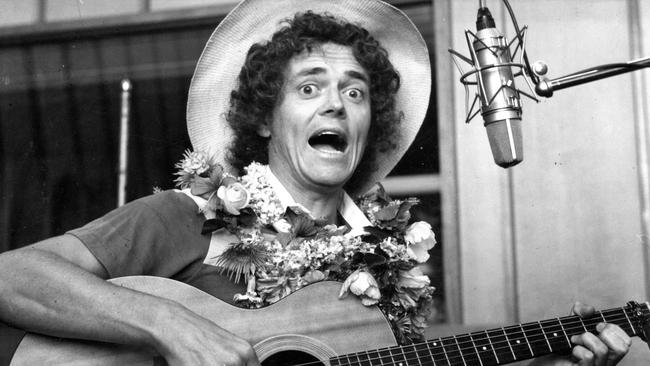

There’s an audible hush in the theatre, that feeling of anticipation that’s unique to live music. The lights go down, a low murmur replaces the silence, and the man everyone has come to see steps on to the stage, an acoustic steel-string guitar slung over his shoulder. He once harboured ambitions to be the next Paul Simon, but life had other plans. More on that later.

The first chords ring out, the crowd starts moving. And dancing. And singing every word. But this isn’t your usual live crowd. For starters, it’s quite short. And young. And the bloke singing isn’t your usual pop star. He’s a singer-songwriter who’s carved out a 40-year career in a notoriously difficult space by writing and performing songs about eating sticky toffee apples and belly flopping into pizzas.

He’s Peter Combe, he’s 74 years old, and he loves making kids happy through music.

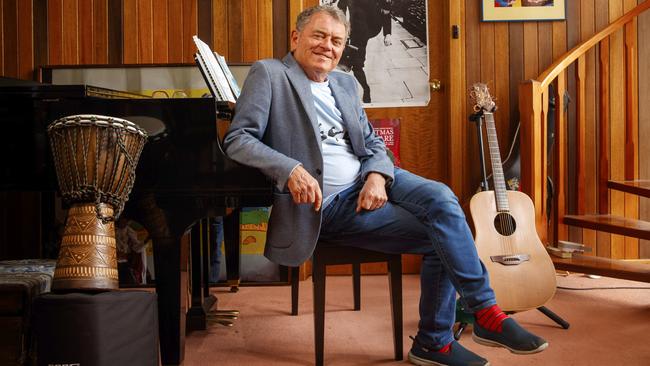

Combe’s sitting on the couch of his comfortable eastern suburbs bungalow.

He looks fit, and says he still runs to keep his weight down to ensure he has the energy needed to perform for crowds of adoring kids. He could easily pass for a man a decade younger than he is.

He spent the first part of his childhood, he says, in working-class Underdale – 1 Stuckey Ave to be exact – playing with the Italian kids who immigrated after the war.

His dad had a love of the Hills, so the Combe family eventually relocated to Beaumont, moving into a newly-built home. “My father was musical, and my two sisters are,” Combe says.

“My brother John loves music too, but I’m not sure how musical he is. He might not even know himself. I guess I’m the only one who took it seriously to the point of making a career out of it.”

That career wasn’t supposed to be in kids’ music. In the late ’70s Combe took his young family to London with dreams of becoming a contemporary singer-songwriter like the aforementioned Simon.

“Of course, there’s only one Paul Simon, but I wanted to write and record music,” he says. And he had some success, recording and releasing a song called Music of the Day and even writing a track called Vagabond for The Seekers.

Combe eventually found himself co-hosting a BBC children’s program called Music Time, which was shown on the ABC in Australia. “But I came back from London in 1980 and, I must say, I regret coming back when I did,” he says.

“If I had my time again I would have stayed there longer. I was co-presenting a show on the BBC in London! What was I thinking moving back to Adelaide?

“But, of course, life is more complicated than that. We’d just had our third child, (Combe’s wife) Carol was homesick and she wanted the kids to have access to grandparents and family, which is understandable.”

Combe arrived back in Adelaide with a bunch of unrecorded children’s songs. A plan to put them on tape fell through when the original backer pulled out, so Combe decided to record and produce them himself. “That became Songs for Little Kids, and that record had Spaghetti Bolognaise on it,” he says. “It was a cottage industry running on me selling cassettes, but it became clear that there was an incredible enthusiasm for this music.”

Combe had, perhaps unwittingly, tapped into something that really hadn’t existed until that point – contemporary music written specially for children. Not nursery rhymes or traditional songs, but modern pop songs with relatable lyrics that spoke straight to kids.

“It’s odd, because people had been writing stories for children for decades, but not music,” he says. “I tapped into something, and it just took off.”

Took off is perhaps an understatement. Combe became a genuine phenomenon.

It was success compounded by the first made-for-kids film clip to get a national release in Toffee Apple, and a success rewarded by several ARIA awards.

It was at one of these award nights that Combe had one of his “pinch me, I must be dreaming” experiences.

“I won an ARIA for Newspaper Mama in 1989, and the keynote speaker was (Beatles producer) George Martin,” Combe recalls. “After the speeches finished all the winners went to a room. Kylie Minogue was there, and she had just become big and was very much the flavour of the month.

“All the journalists crowded around her and wanted to speak to her – which I understood. However, there’s George Martin, who did the string arrangement for Yesterday, who produced every Beatles album, being totally ignored. “To cut a long story short, I got to spend half an hour chatting with George Martin about music. That was a real moment for me.”

But it was at Schutzenfest, that Adelaide celebration of beer and all things German, where Combe discovered something remarkable.

Those kids who had grown up with his music were now adults, and they still loved him.

“That was back in 2004 or 2005, and I did wonder at the time why I, as a children’s performer, had been invited to a beer festival but you know, a gig is a gig,” he says. “Anyway, it was 41 degrees and I was supposed to play outside. So we moved the show inside and when I started playing these young adults literally stormed the stage. I thought it might have been the alcohol talking, but after a while I realised that it was actually a case of mass nostalgia for these songs.”

That experience led to a string of Adelaide pub shows, then a sold-out tour across the nation. Venues full of young adults turned up to drink, dance and sing the songs that were such an important part of their childhood.

Those tours wound down as the young adults started having kids of their own and began coming to terms with the fact that babies wake up early and have no respect for how late you got to bed. But it proved to Combe what he had suspected all along – a good melody is a good melody, and a good melody is timeless.

“The melody is what sticks,” he says. “Words can stick too, but melodies lodge in your consciousness, and there just aren’t that many of them around these days. But to see that there was a genuine love for the songs, I found that very touching.”

Playing for beer-swilling adults mighthave been fun, but it’s the kids that spur Combe on as an artist.

More than 40 years after he recorded his first children’s songs, his popularity among the primary school set is as strong as ever.

He admits that he may have accidentally stumbled on to the secret of musical longevity – ensuring there’s always a new audience coming up that’s immune to the trends and vagaries of an older pop crowd.

“It really is wonderful, and you feel very honoured that they enjoy these songs so much,” Combe says. “I mean, there are certain songs that I’d love to give a two-year rest, but I can’t do it. The obvious one is Mr Clicketty Cane. It would be the height of self-indulgence not to play it though, the children simply want to hear it.

“It’s always the last song of the show, and there’s always an enormous eruption of joy when I play it.”

Combe may have cracked the formula with that song, a tale of a mischievous protagonist who leads the kids in his street through a range of increasingly ridiculous tasks, including washing their faces with orange juice, cleaning their teeth with bubblegum and, of course, belly flopping in a pizza.

“It’s an echo song (where the audience repeats lines), and echo songs are very powerful,” he says. “Then it has the silly punchline. Belly-flop on a pizza! The kids just love it. It’s had more than six million streams on Spotify.

“But children’s work of any worth is timeless. I wrote Mr Clicketty Cane in 1983 and recorded it in 1984, but to a child of five that doesn’t matter one jot. It makes no difference at all when it was written.

“Kids like it or they don’t. They don’t care about trends.”

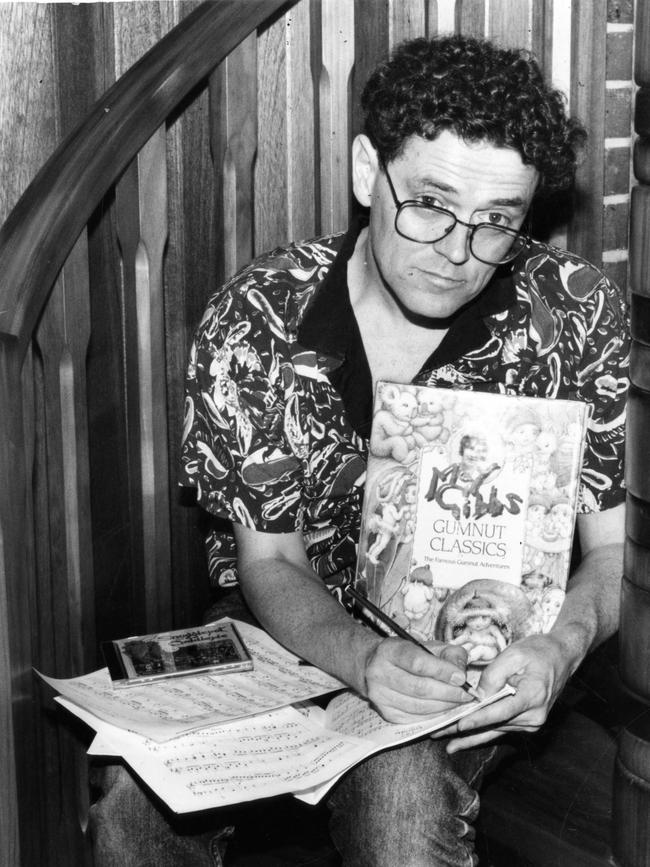

And while that song will forever be a huge part of Combe’s legacy, he says it’s his 1993 musical adaptation of May Gibbs’s classic Snugglepot and Cuddlepie that is his proudest moment. “That’s the biggest thing I’ve ever done,” he says. “It was probably two-and-a-half or three years’ work in the end. Carol did the dramaturgy, which involves taking the book and making it into something you can write music to.

“Then it was recorded with the Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, with Ruth Cracknell playing May Gibbs and Eric Bogle (The Band Played Waltzing Matilda) as the lead Banksia Man.

“It was all recorded live at the Festival Theatre with a 120-voice choir. A mammoth undertaking, but something I’m very proud of.”

Combe says retirement is the furthest thing from his mind.

He’s having too much fun to consider stopping.

There’s a new album in the works, slated for release this year, which will have an ecological bent and address topics such as climate change and the environment – a cause close to his heart.

But before that there’s a run of Fringe shows to perform.

Combe says the death of the physical CD and cassette means live performance has become an increasingly important part of his, and most musicians’, business plan.

“It’s harder to make money as you sell so few CDs these days,” he says.

“You do get paid for Spotify, although I’ve never found out how much you make for a play – it’s next to nothing. So that makes live performing more important, but that’s the way music is going. With vinyl having made a comeback I do wonder if CDs might too. I hate to think music will become something that lives up there and you can never touch it.”

He’s been reluctant to go down the road of hardcore merchandising paved by the likes of The Wiggles – “although there is an Adelaide company that makes wonderful Toffee Apple socks, and at least that’s something useful” – so it’s the stage that pays the bills.

One suspects, though, that Combe would continue to make music even if it didn’t pay a single cent.

“Music makes kids happy,” he says.

“And music feeds the soul. That might be a cliche, but it’s true. It makes us more civilised people. But in the end it just makes people immensely happy, and how could you not want to do that? When I stop enjoying it, and when people stop coming to my concerts, I guess that’s when I retire. So far, that hasn’t happened.”

Combe’s audience encompasses three generations now.

There are the children, their parents who grew up loving his music, and the children’s grandparents who bought the albums for their kids in the ’80s. The spread of ages, he says, creates a “wonderful vibe”.

All four of his kids are creative and musical, and he now has the pleasure of performing and recording with his own grandchildren.

“Five of the seven grandkids have had roles on my albums, and I’ve performed with four – soon to be five – of them,” he says. “I’m very lucky on that front. But I just love working with kids, family or not. I find that 12-year-old kids are often more reliable than professionals. Professionals can become lethargic, but kids never do.”