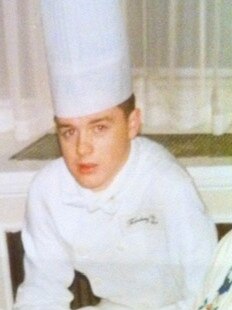

Masterchef’s Jock Zonfrillo on heroin, Orana and setting a workmate’s pants on fire

In 2021, controversial celebrity chef and Masterchef judge Jock Zonfrillo opened up about his “many, many regrets”, including heroin addiction and a childish prank that ended up in court.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Editor's note: This interview with Jock Zonfrillo was originally published on August 7, 2021. We have republished it, in full, below.

Jock Zonfrillo says he did his last shot of heroin on New Year’s Eve 1999, in the toilets at Heathrow Airport. He was 23 and he’d been hiding his crippling addiction from his loved ones for years. Zonfrillo knew it had to stop. He could not keep living the way he was, shooting up in toilets, feeling physically ill and constantly guilty.

“I remember thinking: ‘This is the last-ever time. This is the last shot.’ I would never take drugs again. When the plane landed in Sydney I’d be free of all of that,” Zonfrillo writes in his memoir Last Shot.

And he was free – with a fresh start in a new millennium in Australia as head chef of Restaurant Forty One – leaving that sordid past behind and relieved at never having to face his guilty secret again. Or so he thought.

Fast forward to 2014, when an article broke the story Zonfrillo was once a heroin addict. Reliving that day was the most harrowing part of writing his memoirs.

“I think it was one of the most horrible days of my life, without question, Lisa,” Zonfrillo shares as we chat down the line from Melbourne. “I had to sit the kids down and tell them. And tell my mum and dad. And my ex-wife. Just the feeling of that was absolutely horrid. There’s no getting around that – it was what it was. But that was the hardest part to write about because it brings back all of those emotions.

“There’s a stigma around heroin for sure. I just think that stigma and the fear of people knowing was more terrifying than anything.

“But once I got over how vulnerable I was, all of a sudden there was a sense of relief that that secret that was mine for so long was now revealed.”

In the 370-page memoir, Zonfrillo also shares his regrets, including about the prank on Forty One apprentice Martin Krammer in 2002 that went horribly wrong. The kitchen was full of running jokes, including on head chef Zonfrillo himself.

The Advertiser reported in November that Krammer took legal action against Zonfrillo for setting his pants on fire, resulting in $70,000 damages being awarded by a judge. Zonfrillo failed to pay the damages, prompting Krammer to obtain a bankruptcy order against him in the Federal Magistrates Court.

Zonfrillo confesses: “(Of the) many, many regrets in my life, my conduct on that day is right up there in terms of sheer guilt.”

“Once the dust had settled I had a meeting with the apprentice, his mother, the training company and the restaurant to work it out,” Zonfrillo writes. ‘“I’m very sorry,’ I said. ‘I was playing a joke and it went badly. I accept full responsibility.’

“What I did was egregious, immature, dangerous and I am thankful every day that I didn’t hurt him as seriously as could easily have happened.”

The incident resurfaced in an article last year, just as he was filming Junior MasterChef.

“It was bad enough for (my mother) to live through the disaster ... back in the day, but to revisit now I had a television profile was just the pits. I’ve never stopped feeling guilty about that. It was a dumb prank that went horribly wrong and could have been even more disastrous,” Zonfrillo shares. “All that remorse that had been stewing away at the back of my mind just came pouring out as I was confronted – yet again – with my own reckless past.”

The story gathered momentum on social media and trolls called for him to be sacked.

“The idea that a person might grow into a different disposition and world view 20 years after they’ve achieved renown as a reckless, f--king idiot seemed to be beyond the scope of these people’s understanding,” Zonfrillo says.

So was it therapeutic to delve into his past and share his side of the story?

“No. F--k no. It was horrific,” Zonfrillo says. “I found it so hard for so many reasons. Just writing it was one thing, but dealing with the bad decisions you’ve made all at one time … it’s a hard card. It’s pretty tough. That’s not cathartic, it is just bloody hard.

“As I wrote in the book, I own every single bad decision I’ve made. And I’ve made a lot of them.”

While he was comfortable with the decision to share his story, warts and all, writing – unlike his prodigious talent for cooking – did not come naturally.

It took a good six months of “hard” procrastinating before the words started, let alone flowed. Zonfrillo laughs as he shares he went and bought himself a super nice pen and a moleskin notebook. When they didn’t help, he bought a laptop and downloaded a journal app. Then he decided he needed an iPad and a stylus pen. A new laptop and more apps still didn’t undo his serious case of writer’s block. Wife Lauren walked in on him one day staring at the screen and suggested he turn to fellow Scotsman, former Adelaide boy and great mate, singer Jimmy Barnes, who wrote best-selling biographies Working Class Boy and Working Class Man and has penned the foreword to Last Shot.

“Loz was like: ‘He’s much the same as you – he’s not academic and he had to write a book,’” Zonfrillo recalls.

He rang “the big man”, who proved to be just what the doctor ordered, advising him to get up early, make himself a cup of coffee or tea, lock himself away where no one could find him and go hell for leather until someone disturbed him. So off to the granny flat Zonfrillo went and it all came pouring out.

The result is out now, and some reviewers have suggested his story is a cross between the iconic gritty Scottish movie Trainspotting and Kitchen Confidential.

“It makes sense – there’s a lot of heroin and drug use and the cheffy harsh reality,” Zonfrillo laughs, but demurs when we ask who should play him in the movie.

“Look, this is a whole new world for me. People keep saying: ‘Hey, we want to make a movie out of your book.’ And I’m like ‘oh yeah, sure’. But then there’s follow-up emails and you starting going ‘oh OK, they’re serious’.

“Some have suggested (Scottish actor) James McAvoy for me now. But I think everybody is struggling to think of an upcoming Scottish actor to play the young me. I don’t know. I think I’ll have to leave that to the experts.”

From stealing cars at 11, to drugs and perpetually self-destructive behaviours in his early years, it’s a marvel Zonfrillo has made it to 45.

“It’s weird. For me it was just my life – I never looked at it too abstractly,” he says. “I didn’t know any different, that for me was a normal upbringing. But then you speak to people like my wife after they’ve read it and they go ‘that’s not a normal upbringing for a kid’. Or ‘I would be horrified if my children went anywhere near things you did’.

“The really confronting part came after I finished it and a couple of people read it and it

dawned on me that my past was not normal at all.”

Zonfrillo is philosophical as he ponders why he got into drugs. He grew up in a loving home with his Scottish hairdresser mum, Italian barber dad and older sister Carla. Barry – as he was known then, his nickname Jock coming from his largely European colleagues in the Turnberry Hotel kitchen where he started his apprenticeship at 15 in the ’90s – wanted to be just like his Nonno Zonfrillo, surrounded by children and grandchildren.

“It wasn’t as if I grew up and didn’t have any shoes or something,” Zonfrillo explains. “(My parents) came from a generation of parents who had no f--king idea of what their kids were up to, or the effects of drugs or what those effects looked like or what they did to people.

“Me leaving home so young to go to work obviously had an impact as well. All of a sudden you are a not a child at home. You are a child in an adults’ world and – forget all about the harshness of that work environment, which was f--ked – but you are among fully fledged adults who are completely unhinged for the best part. You are looking up to them as your mentors and teachers, so inevitably you end up mimicking their behaviour. And trying to become them, in a way. So there was a compounding of all the psychological damage I’ve done to myself and this compounding effect from everything in my life that went from leaving home all the way through. And I really didn’t address any of it ’til later.”

It’s hard to reconcile that version of Zonfrillo with the exuberant judge on MasterChef who has helped breathe new life into the much-loved franchise with colleagues – and now firm friends – Melissa Leong and Andy Allen. Worry beads in hand, he’s inspired conversations about mental health and been frank about his own struggles with anxiety.

He’s working on a set of his handcrafted worry beads while we chat. He laughs when I query if he’s shaving – given that’s what it sounds like down the phone.

Those beads, now very much part of his on-screen attire, caused huge audio issues initially for production. The team asked Zonfrillo to keep them in his pocket.

“And then Covid really hit and me – and a lot of people – were struggling. I ended up having them back in my hands again and I was like: ‘You’re going to have to deal with it. I’m not OK. I’ve got to get through this,’” he shares. “It became normal and in that act of becoming normal – and Ten and production understanding – it showed that it was all right to have that conversation. I think so many people suffer from anxiety in one way or another.”

It’s not all doom and gloom. Zonfrillo’s obviously had some extraordinary successes, including winning Young Scottish Chef of the Year at 16, and starting his career with the ultimate rock star chef, Marco Pierre White, in his flagship restaurant in London’s Hyde Park. But establishing Orana – his Adelaide restaurant, which showcased and put Indigenous ingredients on the map – and the subsequent establishment of the Orana Foundation are at the pinnacle of his career achievements.

He says it was heartbreaking for him to close Orana last year. And it took a huge toll on him mentally.

“I miss my team, we had such an amazing team – incredible people who really worked towards starting a conversation to acknowledge Indigenous people and their culture,” Zonfrillo shares.

He and wife Loz had everything crossed they could re-open last August after the temporary Covid closure.

“We pooled all the money we had in the war chest and kept staff on payroll as long as we could and paid out annual leave and benefits for as long as we possibly could. The Orana team was family and we would look after each other,” Zonfrillo shares in the book.

“But we were sustained by the idea that we would reunite on the other side of the pandemic.”

When it became apparent the strict Covid restrictions meant it would not be viable, they made the gut-wrenching decision to close permanently.

“In October we had to put the business into voluntary administration, end our lease and close the restaurant permanently,” Zonfrillo says.

The Advertiser reported in November that creditors, owed more than $1m, accepted a $101,000 cash settlement offer in the wake of the closure of Orana and Zonfrillo’s other Adelaide restaurant, Bistro Blackwood.

The Orana closure was just part of what Zonfrillo calls his “timeline of shit” last year, with allegations also in the media about Orana Foundation. Loz was pregnant with Isla, which was already stressful after the difficult time she had carrying Alfie, who was born several weeks premature in February 2018. They’d just moved their whole life to Melbourne, a new city where neither of them had any roots, in a pandemic.

“For weeks it was a series of media hits that kept coming and coming and we felt there was nothing we could do,” Zonfrillo shares in the book.

The couple set up a “war room” in their Melbourne house. They’d get up in the morning, read the news stories, and be bombarded with messages and calls from their lawyers.

“We’d go into that room and start working with our lawyer to try and untangle everything,” Zonfrillo says. “And I’d have to head on to set every day and smile like nothing was happening.”

He says he wouldn’t have survived without his strong partnership with Lauren.

“We just buckled down and kept family close around us,” Zonfrillo says. “Everybody was very surprised that I didn’t take to social media and let rip. But I knew that was the worst thing to do. And we had advisers who were much more trained in these circumstances than I am.

The couple – who married on New Year’s Day 2017 in a beach ceremony on Mnemba Island in Tanzania – now live in Melbourne with their two children, Alfie and Isla. Zonfrillo’s eldest daughter Ava joined them in the first wave of Covid. And while the pandemic wreaked havoc on so many things, the silver lining is that Zonfrillo has had time to just be with his youngest two. It wasn’t that way with Ava and his second daughter Sofia.

And he’s enjoyed every moment of that family time – even the messy side. As we chat, Zonfrillo has spent the morning cleaning up after Alfie’s gastro. “I’ve managed to avoid all the rugs getting Alfie’s vomit – I’m celebrating that I’m not cleaning rugs right now. It’s small victories.”

While he misses Orana and the restaurant game, for now he’s content to mix family time with MasterChef duties and other business interests. He says he’s been approached to reopen his award-winning restaurant in Sydney or Melbourne.

“People want it back and believe it’s an important part of Australia,” he shares. “I just don’t know. My nonno always said ‘if it’s not clear what the right choice is, then don’t do anything until it is clear’.”

They miss living in the Adelaide Hills – although he admits going through a bushfire season every summer was tough, especially given the amount of time they spent away from their Summertown property. And the upkeep on the 10-acre property was expensive, which also prompted their decision to sell last year.

“But it was a sanctuary – you’d drive up that long driveway and by the time you got to the house you felt like you were in the middle of nowhere,” Zonfrillo says. “We miss the community of the Adelaide Hills.

“Can we see ourselves back there? Well, yeah, we could. But would we? I don’t know. We’re in Melbourne six months a year. We’ve got a lot going on that isn’t in Adelaide, unfortunately.”

As Zonfrillo says, the highs more than outweigh the lows.

“It’s fair to say I’ve had a lot of joy in my life and I’m thankful to have had the life I’ve had,” he shares. “I think of all the travel I’ve done over the years, the places I’ve been – I’ve been very, very lucky. And I’m thankful that somehow, weirdly, I’ve managed to still be alive.”

Last Shot by Jock Zonfrillo (Simon & Schuster Australia $45) is out now.