Marree man: Nature has brushed away world’s second largest geoglyph etched in SA’s red desert

FOR 17 years, the mystery of the Marree Man in SA’s red desert captured the nation. Now, this amazing creation has disappeared. Find out what happened to it and how people want to bring it back.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- SA’s X-Files: UFOs, baffling crop circles

- SA’s X-Files: The Somerton Man, Adelaide’s secret tunnels

- SA’s X-Files: Marree Man, Tantanoola tiger and Nullarbor Nymph

- SA’s X-Files: SA’s most haunted town

- Marree Hotel publican leads push to revive Marree Man

THE Marree Man is gone.

The sands of time, flooding rains and bursts of bush growth have wiped the giant Aboriginal figure etched into the state’s northern desert from the landscape.

After 17 years, the Marree Man can no longer be seen on Google Earth.

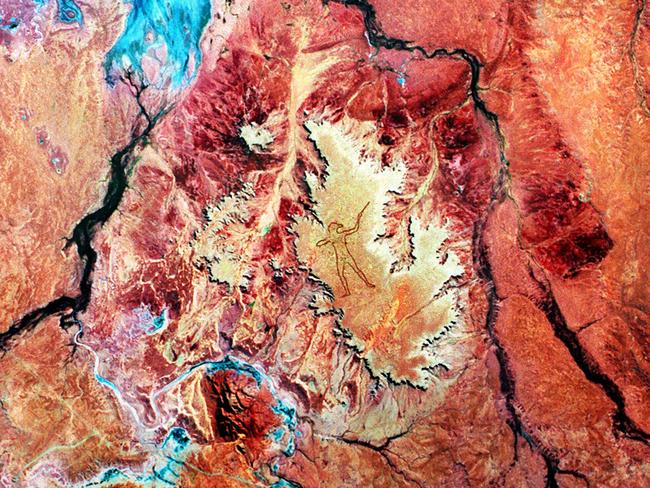

From the air, only the faintest evidence of the mysterious 4km tall carving, 28km in total length, can be found on the plateau on the southeast edge of Lake Eyre South.

Only the eagle-eyed pilots who have flown thousands of tourists over it in years gone by can make out the tip of his throwing stick, a part of a leg or a torso.

It’s a far cry from the bold outline of the Outback curiosity which made headlines around the world and sparked a still unsolved debate about its origins.

On the ground, about 70 per cent of the once 55m-wide outline can be found, broken up and without order. Those remnants will be gone within a year, is the prediction.

And a final nail in the coffin of the giant figure came in April when the last remnants of hope — the trademark “Marree Man” — was abandoned by the Arabana Aboriginal Corporation.

The trademark was to be used to produce souvenirs ranging from books, indigenous artwork, post cards and travel guides and attached to any businesses — coffee shops, bars, hotels and fast food outlets — which popped up as the tourism potential of the site was realised.

While the world’s second largest geoglyph is gone, the mystery of how Marree Man came to be remains.

Local tourism operators are still keen to find a way to breathe life back into the big man, convinced it could drive an estimated $22 million in annual tourism benefits, with the mystery of its appearance in 1998 still fascinating travellers from around the globe.

Marree Hotel publican Phil Turner said the disappearance of Marree Man was devastating.

“It is just reaching its full potential, its glory, now,’’ Mr Turner said.

“Every single day we get people coming out here or contacting us asking where it is — we have to reply: ‘It’s gone’,’’ he said.

Mr Turner and other Far North tourism operators including Wrights Eyre founder Trevor Wright — who it is thought was the first to see the figure — have been pushing to save the Marree Man and establish it as an icon for the SA Outback.

Mr Turner likened it to finding a Rembrant behind a couch which needed to be restored.

“This Rembrant, once restored, needs to be framed right and hung right or there is no point spending the money to restore it,’’ he said.

“It needs to be fenced and protected and the area managed and marketed correctly so there is a benefit.’’

He suggested the artwork should be adopted by the Art Gallery of South Australia and somehow incorporated into its collection, and that the region’s native title holders, the Arabana people, are the perfect custodians and should be granted copyright on the work.

But if the giant artwork is to be reinstated, it will be known as Arabana Man — after the traditional owners of the land on which it was carved — and it will only be repaired on the terms of the Arabana people, said Aaron Stuart, chairman of the Prescribed Body Corporation of Arabana Native Title.

“There are more important cultural artworks right next to Arabana Man that you cannot see from a plane ... rock carvings that are 40,000 years old,’’ Mr Stuart said.

“So, to me, it doesn’t bother me if Arabana man isn’t restored. There are people who are looking to it from a financial benefit point of view, but Aboriginal people are not going to be treated like third class citizens and not get something out of their land while others benefit,’’ he said.

“The Arabana people need to benefit from anything that happens with Arabana Man. If the State minister and tourism operators can’t come on board with this and help the Arabana people to create a sustainable income, then we’re not interested.’’

William Creek Hotel owner and outback pilot Trevor Wright said you can still see some parts of the giant image from the air at certain angles but even his pilots no longer knew where to look and tourism flights are no longer run over the plateau.

The last flight for tourists over the figure was about 18 months ago and Mr Wright says he knocks back requests to fly over the Marree Man now because it is not commercially viable.

“I just don’t see it as value for money for the customer,’’ he said.

“It no longer resembled anything, so we could not justify taking tours over it any longer.’’

Art Gallery of SA spokeswoman Nici Cumpston said there had been no approach made to discuss Arabana Man being included as a recognised work.

“As a public gallery we work with all communities to promote art and make it accessible and enjoyable for the public,’’ she said.

“It would be up to the community involved to make such an approach.’’

Tourism Minister Leon Bignell showed little interest in restoring the figure.

“As far as I know, no one has asked the government to pay for any work on the Marree Man,’’ he said.

“It was the mystery of who did it which made it interesting. People are less likely to want to see something graded by the government.’’

Foreign forces, an offbeat artist and a riddle of the desert

By Bryan Littlely

THE mystery still remains bigger than the man.

After 17 years and with Marree Man faded from the eyes of the world, just who created him has never been solved.

There have been as many myths about the creation of the 4.2km-tall, 28km-perimeter etching on the south-eastern edge of Lake Eyre South as he has had names.

The figure — the second biggest geoglyph ever created, after a “Readymix” logo carved into the Nullarbor Plain in the 1960s — has been known as “Big Man”, “Stuart’s Giant” after outback explorer John McDouall Stuart, and “Arabana Man”

Goldberg, who lived much of his time in Alice Springs, reportedly told friends he’d been paid $10,000 to create the etching, shown people a plan for it and had even reportedly bought about $600 of diesel fuel for the tractor used to create it. But he never confirmed it before his death in 2002.

Press releases that followed the discovery by a pilot on June 26, 1998, contained terms more likely to be used by Americans — “your State of SA”, “Queensland Barrier Reef” and “Aborigines from the local indigenous Territories”.

That and a mention of the “Great Serpent” in Ohio threw a spotlight on US forces based at nearby Woomera, who were more likely to have access to the GPS surveying equipment needed to create the artwork.

Six months after the discovery, a tip-off led to a pot being found near the outline, which pointed more to US involvement. It contained a US flag and a note with the words “Stuart’s Giant” and a reference to the American cult the Branch Davidians.

A quote on a plaque also found at the figure comes from a passage of the book The Red Centre, by H.H. Finlayson, which describes hunting with throwing sticks and includes photographs of hunters without loin cloths and with other details similar to those of Marree Man.

No witness to its creation has ever surfaced.

At the time its discovery grabbed world attention, the area was part of a legal battle to determine the traditional owners. The area was claimed by the Arabana and Dieri Mitha peoples. The Arabana people were granted native title in 2012 and are the custodians of Arabana Man.