Leading QC Marie Shaw’s daughter, Rachael, follows mum’s philanthropic footsteps

UNORTHODOX, hardworking and driven by a desire to help the less fortunate, Marie Shaw, QC, is not your typical Adelaide lawyer – nor is her daughter Rachael, with whom she shares a legal practice and a passion for social justice.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MARIE Shaw talks a lot about the people in her life who have beaten the odds and found their own path. She calls them “square pegs in round holes” and she includes her youngest daughter, Justine, and although she doesn’t say as much, she means herself as well.

Shaw, in her 60s, looks like just another relentless high achiever in Adelaide’s legal community; a QC with a stint on the District Court Bench, and a string of high-profile criminal trials, including suspected thrill killer Bevan Spencer von Einem, one of the accused Snowtown serial killers and, more recently, Henry Keogh, whose conviction for killing his wife was set aside.

Up close she is not quite what you expect. She is attractive but her battered old watch has seen better days and her court uniform of navy blazer and skirt doesn’t look designer.

Nor does she cellar fine wines and winter over in Europe like many of her colleagues. She shares chambers with her daughter Rachael, another unconventional spirit, making them a rare mother-daughter legal partnership in South Australia’s heavily male-dominated legal profession.

Most surprising of all, she is a dedicated philanthropist and devotes most of her spare time and not a little of her money to the Ice Factor program that helps troubled teenagers who the system is ready to spit out. “I’ve got no money, I gave mine away if I ever had any,” she says blithely.

What makes Shaw different is that she had to fight her way to the top from a small country town on South Australia’s remote west coast, which left her with a sense of disadvantage. She also bears the scars of having to wage a very personal fight to educate Justine, who has dyslexia.

Shaw’s family life at Warrachie, near Elliston, left her with a burning determination to achieve an education, something her father had been denied. At boarding school at Loreto College, she had the revelation that she could use hard work to overcome a sense of inadequacy and low self-esteem.

“I got to Year 11, didn’t regard myself as particularly bright,” she says. The turning point came when her economics teacher told her: “Marie, I think you can top the state in economics”. “What! Here is someone who is telling me I cannot only do it, but be the best at it,” she says. “And I did.”

She fell into debating and won an American Field Service Scholarship to live in the US for a year, where she became part of an American family. At a home near Boston she was treated like one of their own and called her foster parents Mum and Dad.

“My American mother was the person from whom I learnt the ability to understand the gift of unconditional love, from a stranger,” she says. “It changed my life. I learnt there was another way to live, that my life was not the only way.”

She came back driven – but not just for personal success. She wanted to channel her new-found worth into something positive and that ambition still frames her life.

“I (knew) I could find happiness if I got my value in life out of giving, rather than material things and status,” she says. “It shaped what my goals would be.”

She fell into law, partly because of a tall, dark young police cadet, Phil.

She was working at Woolworths on The Parade and became friends with another young girl who worked there. One day, she discovered Phil was her friend’s brother. Did she want to meet him, the friend asked?

Her marriage to Phil is a rare thing among barristers; a first marriage still going 44 years later after all the stress and absences the career demands. Shaw puts it down to his supportive nature. “Nothing to do with me, I can tell you,” she says.

Not long after they were married, a friend told Phil that he knew the criminal lawyer Frank Moran through a football club connection and if his wife needed a job, he would speak to Frank for him. “Isn’t this Adelaide?” Shaw laughs.

Moran, regarded as a great criminal lawyer who was Queen’s Counsel and later a District Court judge, had a reputation as a Rumpole of the courts and a supporter of the underdog,

He and Shaw shared a strong Catholic background – he had 12 children, Shaw’s uncle was a priest – and a burning desire for social justice. He taught her not to be scared of humiliation in front of the bench, which is every young lawyer’s secret fear. They can’t kill you, he told her, just keep going.

“He had no fear of authority,” says Shaw. “He put his client’s needs before the need to appease the bench.”

He also paid great attention to detail. The first case she juniored with him involved a man who had been charged with death by dangerous driving after hitting a boy on a bike. Moran got a metallurgist’s report then a physics expert from the University of Adelaide to testify that the boy’s bike light had the wrong globe and he could not have been visible. It was the start of her career as a defence lawyer, never a prosecutor. She wanted to emulate Moran’s courage in defending the underdog, who in some cases were the worst of the worst.

She acted for von Einem over the alleged murders of Alan Barnes and Mark Langley in 1990; and in the Snowtown case for Mark Haydon. Both charges against von Einem were withdrawn (he was convicted of the murder of Richard Kelvin two years later) and Haydon was convicted of assisting seven of the grisly killings carried out by John Bunting and Robert Wagner.

“Frank would say how he was constantly asked ‘how can you act for these people?’ and he would say to me: ‘I’m not God; I wasn’t there, so I’m not going to play God and make a judgment about whether they are innocent or guilty,” Shaw says. “The lawyer’s role is to ensure that whatever their defence is, it is presented as strongly and clearly as possible.”

She says she doesn’t know whether clients are guilty or innocent; she gets her instructions and takes them to court. She has knocked back only two clients over the years because of an emotional aspect to their case that she could not overcome.

“There are things that can impair your objective judgment but they are very rare,” she says.

Her capacity for hard work is probably typical of those at the top of the law profession but she has not made it easy for herself.

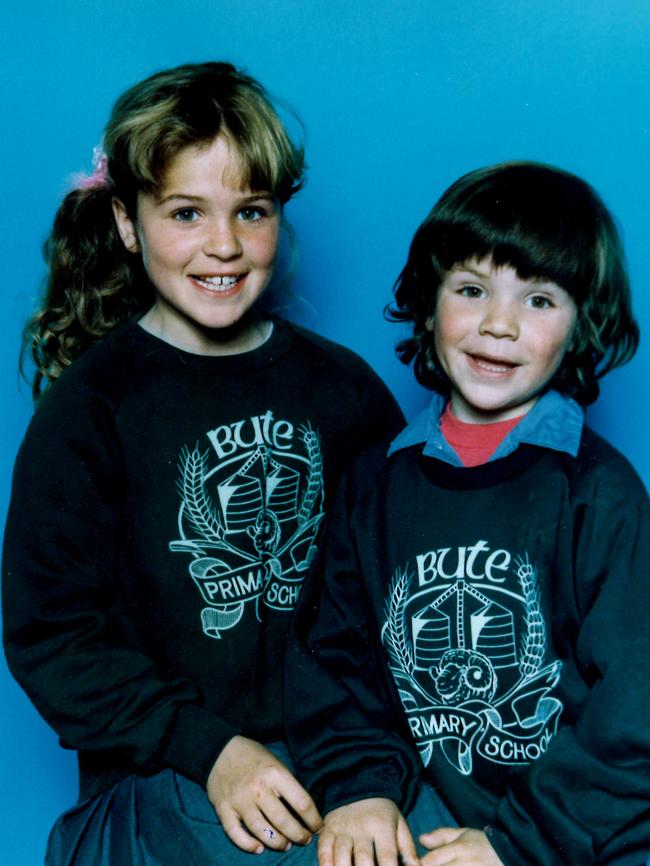

Daughter Rachael, 37, came first, followed by a son, at which point Shaw decided she wanted them to grow up as she had, living in the country. So the family moved to Bute, a farming hamlet 140km from Adelaide along Highway One where they had turkeys, hens, sheep and a goat. For two years, this was her daily commute.

On weekends she threw herself into country sport – on top of everything else she is athletic and a keen netballer – even if not all of the locals knew what to make of her. In a newspaper story more than 20 years ago, one described as her “the most incredibly different person to ever hit Bute” and more than a few of them wondered why she was there.

After two years they bought a small farm at Mallala, which they still have, while Shaw had her third child, Justine. It was the start of a difficult journey that brought her indirectly to her great passion, which is the Ice Factor.

The Mallala commute was shorter but the rest was a great deal harder, starting with Justine being expelled from playschool because the teacher could not cope.

Her parents had known she was high-spirited and expressive but now she was being labelled as a problem. “This is the beginning of the parents being absolutely mortified,” Shaw says.

“We had encouraged her to be spontaneous and love the world but she has a very unusual character. There is no other side of her, just go, go, go.”

It was small things, like playing in the rain so a teacher who chased her got soaked. The parents thought playing in the mud was funny but the teacher didn’t. Underlying the extroverted behaviour and innocence was also a diagnosis of dyslexia. They tried various schools, and one recommended Justine be put into an alternative learning program. “Rubbish!” says Shaw. “My child is not going to be steered down that path when she is still so young. I think she’s gifted. So I rang up a gifted students’ counsellor.”

She explained her child might not yet be able to read or write but there was nothing wrong with her brain, or her creativity.

When Justine was nine the family visited St Petersburg and she became fascinated with the story of the murdered children of the Tsar.

From that time on she was obsessed with the stories of the children of monarchs, and still is.

Justine also loved The Mighty Ducks, a 1992 film about a ragtag ice hockey team coached by a disgraced former lawyer.

She started skating and finished her schooling at St Peter’s Girls’ as a state level ice hockey player, the only girl among the top boy players.

Then Shaw noticed something odd.

“When I started speaking to the (ice hockey) mothers I started learning there were others out there whose kids were dyslexic,” she says.

“It requires risk-taking, a sort of drama and an awareness, that’s the big thing. For some reason a huge proportion are either dyslexic or have ADD.”

In 2005 she was a Queen’s Counsel and about to become a judge when the not-for- profit South Australian Ice Sport Federation, who were trying to take control of the Ice Arena business, asked her for help.

Three previous owners had gone broke and the Thebarton rink was up for sale but had no buyers. They wanted to lobby the State Government to convince them to keep it.

“So I went to see Nick Xenophon which is what you do when you want something done in this state,” she says.

Labor Minister Michael Wright came on board followed by Tourism SA and the Liberals and the arena was saved, with the Ice Factor program built in. The rink runs as a not-for-profit business in which paying users helps support the Ice Factor program.

Shaw had seen kids in court and knew what they had been through to get there – a trail of truancy, dysfunction, alcohol and drugs. She thought ice hockey might help these square pegs in round holes who couldn’t cope with school.

The first 15 Ice Factor kids were from Parafield High and they were from “the dungeon” where they went during the day instead of normal lessons. Some were homeless and addicted to drugs, and had been in trouble fighting or stealing cars.

“That was our first pilot project and that was 12 years ago,” she says.

She is passionate because it works, not for all but for some. The first group of teenagers, who called their team The Reapers, went for two hours a week for eight weeks and had to go from nothing to competent on their skates. No matter how good or bad, everyone got ice time.

“One of the kids who was homeless, Bill, he’d never had a birthday party and on the ice, we had a birthday cake and the kids skated out and gave him a cake there on the ice,” she says.

“It’s about creating a relationship, saying ‘we care about you, we respect you and want you to get the best out of life’.”

Shaw is incredibly proud of the letters she receives from the students. One of them represented Australia at the Youth Olympics; a group of them sat wide-eyed when a woman told how she had killed someone in a road accident and everything changed forever in a minute. “Can you imagine how powerful it was for those kids to hear that?” she says.

She then raised the stakes by organising annual Ice Factor Spectacular fashion parades at the Hilton Hotel. She wrote to the manager asking for use of the ballroom for 80 “at-risk” youth, thinking they would be nuts to agree to it but they did.

At one of the parades a girl, Mary (not her real name), whose arms and legs were lacerated from self-harm, played guitar – with heartbreaking beauty, Shaw says.

Mary later spoke to the Lion’s Club at Modbury about having an alcoholic mother and how she used to cut herself to get away.

This kind of commitment rubbed off on Rachael Shaw but she did not want be like her mother, not at all. She would see the way work kept her up until the early hours and she didn’t want that sort of life. “My mother never wanted that for me either, she wanted me to be an actress,” says Rachael.

She started a film and screen studies degree at Flinders University but loved legal studies so much that end of her first year she transferred to law at the University of Adelaide.

“I think (Mum) was secretly pleased because I had come to that on my own,” Rachael says. “It began this fantastic conversation about the law that continues to this day.”

The problem was how Rachael would find a niche outside of the shadow of a mother whose reputation was cast so wide. She went to London to finish her degree and found a job as a paralegal manager, which thrilled her.

“I needed to do that so I knew I had the ability, and I hadn’t got a job because of my mother,” she says. “It was important for me as a young adult to know that.”

After graduating, she stayed overseas to work out if the law was what she wanted. The commitment, the stress, the worry and the failures were daunting, as was the plight of some of some clients. She was working for a criminal law firm in the UK when she heard about the death penalty cases in the United States and how people were all but rotting in cells on death row waiting to be executed, even when their alibis had not been properly explored.

“I decided to do something – I couldn’t come up with a reason not to,” she says. “I wasn’t married, I didn’t have a mortgage. I felt like it spoke to me.”

She applied to go to Tennessee where about 100 men on death row were managed by six lawyers. She wrote asking if she could volunteer, and they said yes.

She was there for about six months in all, living in Nashville. It was confronting. She would sit down with the prisoners and go through their stories so she could provide the American lawyers with personal research that might help their case.

“Very few of them had proper innocent claims; most of them had incredibly unfair trials,” she says. “If (these) matters had been put before the jury and considered by the jury, they would not have been sentenced to death.”

But she learnt quickly that unfairness doesn’t count, and that being innocent was not enough to save someone who the odds were so stacked against. Most of them were so poor their families didn’t have cars and many were imprisoned in Nashville, a three-hour drive from the black communities in Memphis where many were from.

One prisoner, Daryl Holton, a white Gulf War veteran and confessed killer, became a friend. He was a volunteer, someone who wanted to die and did not want his case appealed. The law office asked her to develop a relationship with him and see if she could change his mind. She visited him almost every day and a month later, he agreed his case could be opened. It was horrific. He had lined up his four children and shot them in the back of his head. He intended to shoot himself but turned himself in. He represented himself at trial and was condemned to death.

Talking to him, Rachael learnt Holton’s greatest fear had been to lose his family. When he returned from the Gulf War he found his partner living in a drug house with the children. He tried to get them out but couldn’t, and decided they were all better off dead.

“I developed a really good relationship with him, I liked him a lot,” Rachael says. “We spoke about politics. He was very learned. I cared for him in the sense that I wanted his appeal to succeed because I didn’t see what use would come from taking his life. It was senseless to execute him.”

He won a stay for 12 months just as she moved to Canada and they wrote to each other. Rachael told her mother about him and she wrote to him too. About a year later she was back in Tennessee to be with someone she met while she was living in Nashville, a musician to whom she is now married.

She visited Holton just before his execution, which he requested be done by the electric chair. It was part of his moral code, payment for what he had been done.

Her instinct was to hug him but she refrained, worried that physical contact would feel too foreign after 15 years on death row. She’s not sure now if that was right or wrong. “I didn’t hug him, I just shook his hand,” she says. “He was executed that night.”

She still has a letter from him, sent while she was in Canada, saying that the experiences she was having would benefit her in later years and that he would like to hear about her plans.

“I understand if you’re busy,” he wrote. “In any event, I’ve been lucky to have had your friendship. Take care, Daryl.”

His death was covered by The New York Times, with a story that explained that although he knew lethal injection was painless, he wanted the electric chair.

After two years in Alabama, Rachael and Drew, who is a chef as well as a musician, came home, just as she was turning 30. He loves Adelaide and Rachael started seeing her home through fresh eyes. A few years later she and lawyer Joseph Henderson, who worked together at Tindall Gask Bentley were looking for offices together, which triggered Shaw to move out on her own after six years sharing rooms with Michael Abbott QC AO.

“Shall we look for a place together?” Shaw asked Rachael. “I don’t care where it is as long as it’s close to the courts.”

At their King William Street office, they have their own clients but mother and daughter share pro bono cases, particularly when prisoners write to Shaw asking for help.

As a barrister, she cannot write back directly so Rachael, who is also a solicitor, steps in. Similarly, if someone who went through the Ice Factor program gets into trouble, Shaw passes it on.

Now comfortable with her own life, Rachael is immensely proud of her mother and doesn’t mind comparisons. “People often say I look like her which is a huge compliment, and people say I am very different to her in court, in the way I advocate,” Rachael says. “I like that as well because I’m not trying to be like her.”

After reshaping her life from humble country beginnings, the one shape Marie Shaw couldn’t quite mould herself into was that of a District Court Judge.

She was appointed to the Bench in 2005, which is a professional pinnacle for many in the law, but four years later, she resigned.

She still won’t talk about why she stepped down. She accepted the role when Justine was going into secondary school and needed a lot of support. The bench gave her more control away from the pressure of criminal trials which isolate barristers from their lives. And it was a great honour, of course, given her low expectations of where life might take her.

But it was complicated by her belief that in most cases, incarceration doesn’t work. “There is no doubt there is no rehabilitation in prison, there is no doubt that if you go to prison you will be forever scarred,” she says. “Rehab is at odds with imprisonment. Having said that, there are people for whom there is no rehabilitation.”

Some of her sentencing was seen as too lenient, particularly a case in November 2006 when she imposed a suspended sentence in relation to a sexual offence. Family First MLC, Dennis Hood, called for her to be sacked, she sued for defamation, he apologised and retracted.

One year later she resigned but says she doesn’t think she was out of step with her colleagues on the District Court Bench. “Not out of step — I probably paddled my own canoe a bit in that I didn’t really turn my mind to what other people thought of what I was doing,” she says. “I wasn’t trying to fit in with some other judge’s approach.”

She was never entirely comfortable with the strictures that being on the bench imposed; the way she would walk down the street and her friends would call her “Your Honour”, as they are obliged to do. And she couldn’t wear her joggers, her usual weekend clothing, in public any more.

Having left the bench, she is happy again as a free-spirited barrister who can fight as hard as she wants for her client’s rights. Friends like Abbott convinced her she was better suited to being an advocate than trying to play the umpire. “Others might say I’m a bit crazy and I’m happy being that way,” she says.

Helping others is still the touchstone of her life and it is the Ice Factor program that drives her and gives her a sense of her own value. “This program is preventing so many kids from ending up in the criminal justice system — and not costing the state $100,000 a year,” she says. “So many of them go on to have very strong and productive lives.”