How Operation Flinders is changing the lives of troubled teenagers in Outback South Australia

Take a group of troubled kids, plant them in the bush for a few days, and watch the magic happen. See the videos.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It’s dusk in the northern Flinders Ranges and a group of weary humans sit around the campfire, resting their limbs after another hard day’s toil in the bush.

They warm their hands over the fire as the flames flicker and dance in that beguiling mixture of colours which mirror almost identically the majestic orange hues of the sunset which has taken hostage of the horizon.

They sit on logs and chew the fat as the fire does its thing and gradually abates, creating the coals upon which their dinner will soon be cooked.

It’s a quintessential and timeless Outback Australian scene – one which could have come straight out of a Banjo Paterson or Henry Lawson poem.

But the protagonists in tonight’s scenario are far from the wizened bushmen of the late 19th century. In fact, the weary bodies hunched over the flames are teenagers from suburban Adelaide who are infinitely more accustomed to staring at their phones than into the mesmerising interior of a campfire.

Until a week ago, none of them had experienced the Outback before.

But they’ve spent the past seven days hauling heavy backpacks across rugged terrain and sleeping rough. In the process, they’ve learnt a lot about life in the bush. They’ve learnt a lot about each other. And they’ve learnt even more about themselves.

They’re all students in year 9 or 10 at Woodville High School, and the past week has transformed their lives. They’re the latest participants in Operation Flinders, a not-for-profit, volunteer-run organisation which has been rejuvenating young lives for more than 30 years.

And when SAWeekend asks them to describe their experience of the past week, they’re universally effusive. Now. If we had asked them five days ago though, it would have been a different story. But more on that later.

Letoya, 15, sums it up eloquently.

“This experience was something like I thought I would never do in my life,” Letoya says. “But I’m glad I did. It’s made me see what I’m capable of and I’ve been able to push myself to my limits, if not beyond.

“I just recommend it to anyone who does have a lot on their mind, or is going through a lot at home, at school, personally, mentally, physically, because it helps in so many ways.

“It does get hard but in the end, the joy of getting to the final night where we are now … it’s just amazing.”

Operation Flinders participants are all SA teenagers whose lives are often at the crossroads. They might come from dysfunctional families. They might be victims of abuse. Their attendance at school might be waning. They might have already found themselves on the wrong side of the law. They might suffer from social anxiety and are struggling to find their niche. They might have been bullied, or they might have been accused of bullying others. Or they might simply have been falling behind at school.

Regardless of specifics, all participants find themselves in life situations which are less than ideal and have been identified by their schools as needing a reset.

So they jump in a bus, usually 10 kids from the same school with a couple of teachers, and make the long trek up to Yankaninna Station, about an hour by dirt road east of Leigh Creek and seven hours north of Adelaide.

Their bus will eventually come to a halt somewhere along a narrow, rugged, dirt track and the teenagers will be ordered off and directed to a tarpaulin upon which they’ll find a backpack they will soon learn to hate.

They’ll be given a team name (the Woodville High kids are Tango 3), meet two Operation Flinders volunteers who they will come to rely on as their team leader and assistant team leader. And then they’ll start walking.

Over the next seven nights and eight days they’ll walk more than 100km, lugging heavy backpacks and sleeping gear across rocky, rugged and sometimes mountainous terrain.

There will be no showers. They’ll sleep on the ground in small swag-like hoochies and will battle physical ailments such as blisters, sprained ankles, sore backs, twisted knees and more.

But their mental battles will be more significant. They’ll be pushed well outside of their comfort zone. They’ll spend a lot of time in their stretch zone and many will arrive in what psychologists call a panic zone – a state of mind in which fear, confusion, anxiety and vulnerability reign.

There will be times, usually after the first couple of days, when they will want to give up. Some of them will lash out. Some will simply refuse to move for hours. Others will run into the bush in an attempt to escape the grind of hours upon hours of walking.

But after a few days, once they become accustomed to the tired limbs, the twice-daily chore of setting up and packing up camp, the uncomfortable bedding and the cold, heat, wind and rain that mother nature throws at them, the healing power of the bush will start to weave its magic.

And so now, on their final night, these teens from Woodville High are basking in the glory of what they have achieved. They can reminisce with a laugh about the second day, when they all wanted to go home.

Let’s let Charlise, 15, pick up the story.

“Day two was a literal nightmare,” she says, her face glowing in the light of the fire. “It started off pretty good, but we had to walk, like, 15km or something, and I think all of us just weren’t really ready for that at the time.

“We got to camp really late and we were, well I was, mentally struggling so much that day. I was, like, done. I was past my limit.”

There were lots of tears on that second day but, with some help from their team leaders and support teachers, they pushed through. It was a turning point and a key moment in their physical and emotional journey.

It’s a journey which inspired former participants Gino Tiburzi and Rachel Currie to such an extent they wanted to return and give something back. To help others who, like them, had a less-than-ideal home life and were at risk of straying from the straight and narrow.

Tiburzi, 17, admits he was “off the rails” before attending Op Flinders as a 14 year old. He dabbled in drugs and treated school and authority figures with disrespect. He admits to urinating in a bin at school and throwing chairs at teachers.

“I grew up in a tough patch – I wasn’t really like your average school kid,” he says as he waves away a fly in the shadows of a new high ropes course at Yankaninna.

“This (Operation Flinders) was a huge turning point for me. You’re out here and you just understand, like, how grateful you are for things at home.

“I guess because you get pushed to your limit, I guess you kind of find who you really are.

“You get pushed so much out here that you just become someone new … It’s kind of like a personality fix.”

Tiburzi says the connection participants make with nature is critical to the type of wilderness and adventure therapy offered by Operation Flinders.

This is his second exercise as a peer group mentor, and this week he is walking with a group of Hallett Cove School R-12 students, offering them the kind of support and advice which can sometimes only be delivered by a contemporary who has recently faced the same type of challenges.

He openly admits Operation Flinders changed his life. After being on a collision course with juvenile delinquency, he’s now moved out of home and is working as a baker with Adelaide Bread Supplies, from which he has taken two weeks of unpaid leave to be up here.

We are speaking as the Hallett Cove boys navigate the high ropes course, a 12m-high, 40m-long combination of poles, wires, ropes, platforms, obstacles and bridges designed to test participants and build self-confidence.

The high ropes opened earlier this year and, along with an abseiling cliff a few kilometres away, provide a sometimes-welcome but sometimes-feared alternative activity to break up the monotony of walking.

There were no high ropes when Rachel Currie, now 26, participated in Op Flinders a decade ago but that doesn’t stop her looking back on the experience with high praise. Currie, who moved out of home when she was 14, describes herself as being tough, isolated and determined to manage on her own before participating in Op Flinders. But eight days of trudging across the rocks and red dirt of Yankaninna opened her eyes to the need to embrace others and let them into her world.

“I was very much trying to be tough – I don’t need anyone, I can take care of myself,” she says. “That definitely gets stripped away – you need the camaraderie, you need the support and friendship out here. You can’t do it on your own.”

Currie says her experience with Op Flinders sparked an interest in becoming a youth worker (she now works with people in state care) and a love of nature. “Usually by the end of day four or day five (when you’re here as a participant), you really start to notice the smaller things like little flowers or birds chirping,” she says.

“I feel like it almost created neural pathways to start focusing on those little moments of beauty that I always let escape my vision before. I think having all of the distractions or the technology peeled away – and my own safety group, because I wasn’t out here with my best friends – it really got me to step into my own two feet and start thinking: ‘Actually, what kind of person do I want to be? Because the person that I am, I might not be so proud of at the moment, but I’ve got the capacity to change all of those things if I really want to, and I’ve been shown out here that I can be the best version of myself. And all I have to do is try – all I’ve got to do is be open to that experience.’”

Currie and Tiburzi are among more than 300 active volunteers who all speak with reverence about the difference Operation Flinders is making to its teenage participants.

It’s an organisation which has been making a difference since founder Pam Murray-White came up with the idea of using nature therapy to help troubled teens back in 1991. The equivalent of 12 full-time staff now support the volunteers and Op Flinders has helped nearly 10,000 young people discover both the harsh wonder of the Outback and learn invaluable life lessons.

Murray-White, who died in 1995, said the program aimed to address the fact that “the kids with the real behaviour problems seem to lack the direction, self-esteem, decent challenge and good role modelling”.

The program has evolved over the past three decades and now has a mission of “creating opportunities for young people facing challenges through adventure therapy programs that provide demanding experiences, personal development and pathways to wellbeing and life success”.

Participants are carefully pushed to their limits by trained team leaders with a view to bolstering self-confidence, self-esteem and gratitude, and improving their ability to work in a team and accept responsibility.

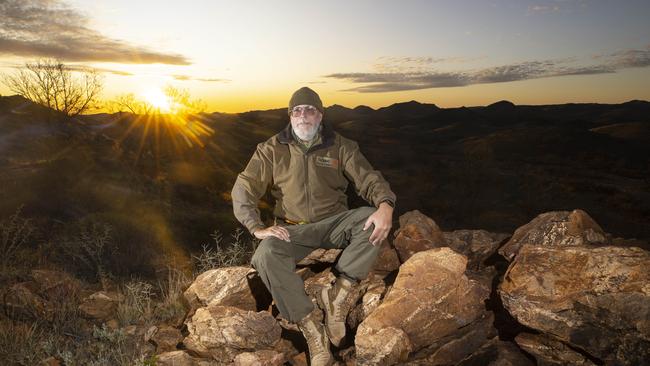

There are generally five exercises each year (the last one of 2022 finished on Friday) and each one is run with military precision, thanks in no small part to the tireless efforts of logistics manager Mark “Thommo” Thomas, a former soldier who was one of Murray-White’s first team leaders in the early 1990s. Thomas, 64, is one of a handful of Op Flinders stalwarts who worked with Murray-White and was a volunteer team leader for more than two decades before accepting a paid role as logistics manager “as his transition to retirement”.

He’s a revered figure among the staff and volunteers, many of whom are former participants who benefited directly from his no-nonsense style of mentoring. He freely admits he could have easily ended up on the wrong side of the law himself when he was a troubled teen who had grown up without a father. But he joined the army instead, where he encountered the type of positive male role models who had been missing from his life. It’s the idea of providing a positive role model for young people that attracted him to the Op Flinders concept.

He spent 10 years in the army, mainly in signals and communications, and then joined the army reserves. He’s held jobs ranging from driving public transport to running his own tow truck business and says the skillset required for his current job is the culmination of all of his previous occupations.

He spends months every year up here at Yankaninna but takes special joy when he runs into former participants back in the big smoke.

“Some young people, who I’ve managed to meet up with many, many years later, will come up and say they remember me from this,” he says as we watch the sunrise gradually illuminate the Yankaninna hills. “They’ve now got a job and have their own kids … Many of them have gone on to have successful careers. Some have become police officers. It’s really opened their eyes up and acts as a circuit breaker.

“That’s what I needed when I was younger.”

The behaviour of the young people, especially during the first couple of days of their exercise, can often be defiant, and it’s not uncommon for participants to either refuse to walk any more (the sitters) or run off into the bush (the runners). Either way, Thomas has seen it all. There’s a tried and tested formula to deal with either situation.

“It could well be that a young person will just refuse to walk – you’ll get the usual rhetoric of ‘you can’t make me’, ‘this is cruel and unusual punishment’ and ‘I’ve got rights’,” he says.

“We don’t overtly force anybody to do anything – it has to be their decision to put one foot in front of the other. So (we get them moving) through negotiation, explanation. And, generally, if the young person doesn’t want to walk we point out that ‘OK, you want to sit here, but your food’s over there.’

“Most of them will eventually get hungry and decide they’ve got to walk.”

And the runners? Thomas says most of them soon realise they could easily get lost in the bush, so they usually find a creek bed in which to sit down and blow off some steam.

“I’ve had some young people who I might find down the creek after they’ve stormed off, just sitting there throwing rocks,” he says.

“I’ll just go down quietly, sit down alongside them, and I’ll just start throwing rocks with them. And I’ll do that for 10-15 minutes. And then I’m like: ‘What are you aiming at? Let’s put a tin out there and see if we can get a stone in it.’

“They engage a bit in the game and then it could be 15, 20 or 30 minutes later when you say: ‘What are you going to do today? Where are you going? What’s your intentions?’.

“You don’t just go in there and say ‘come on, you’ve got to join the team, get your act together.’ You sort of work your way around, get a bit of rapport going with them.”

There are 158 people on the property tonight, 81 of those are teenage participants in nine teams. There’s a handful of paid employees and the rest are the volunteers who pay their own way to get here from all over Australia to give up their time and participate.

All these people need to be fed and watered and so, before each exercise, more than eight tonnes of food will be trucked from the organisation’s warehouse in Edwardstown.

Four or five days before participants arrive, volunteers distribute rations to the more than 20 campsites dotted around the 56,000ha property.

Volunteers also ferry 10,000 litres of water, either pumped up from bores or captured on the roofs of the many various buildings which make up the Yankaninna base camp, to the campsites, and ensure there is enough equipment and back-up equipment for up to 12 teams of 10 teenagers and their support staff. There are also long-drop toilets to dig and firewood to source. Participants and volunteers will need between five and 10 tonnes of firewood per exercise but no native habitat is cleared – dead wood is either collected from the ground or transported from Leigh Creek or Adelaide.

There’s a buzz in the Yankaninna base camp mess room tonight. Tomorrow is an extraction day, when three of the nine teams will be picked up on the side of a dusty track, hand in their backpacks and head back to the real world. The logistics of removing 30-40 people from the property, without the participants ever seeing base camp, are complex. There’ll be buses arriving from Adelaide or Leigh Creek to ferry them back; their backpacks, hoochies and other equipment needs to be collected and stored, ready for the next cohort; and teachers, team leaders, assistant team leaders, peer group mentors and others in the field will return to base and enjoy their first shower in over a week.

Chief executive David Wark, 57, is constantly blown away by the commitment and passion of the volunteers, and inspired by the positive impact their work has on the young people.

Wark has been in charge of Operation Flinders for nearly three years, after previously heading up Vinnies SA, and says it’s a privilege to be involved. “The nature of so many of the people involved is inspirational,” he says during a visit to another part of the property. “The work they do and the commitment they show to the organisation, the passion for the cause, is inspiring.

“There’s a culture in the place for staff and volunteers, it is really hard to put your finger on, but it’s a little like the time the president of the United States visited NASA, and spoke to the janitor and said: ‘What do you do here?’. The janitor said: ‘I helped put man on the moon.’

“In Operation Flinders-speak, you can talk to anyone about the role they do and, invariably, they’ll say it’s all about the kids. So regardless of whether they’re scrubbing floors, or repairing vehicles or replenishing packs or doing whatever, they will say it’s all about the kids. They want to make sure they’re providing an environment that young people can thrive in. It’s just a great place.”

That’s why volunteer team leader Katherine Nugent, 53, keeps coming back. Clare-based Nugent built a successful career as a lawyer before branching out into gin making. But she’s taken two weeks off to be up here to volunteer as team leader for the aforementioned Tango 3 – those kids from Woodville High who are sitting around the campfire chewing the fat.

Nugent’s voice wobbles with emotion as she explains why she keeps coming back. This is her 10th exercise. “I love taking groups of young people out into the far northern Flinders Ranges where our goal is to help them experience the magic of the wilderness, and let the wilderness work its own magic on them,” she says as we watch some of the Tango 3 girls pose for a sunset photo for SAWeekend. “The goal of Operation Flinders is to transform young lives and, as a team leader, I get the privilege of actually seeing it in motion – it actually works.”

Nugent says this group from Woodville High is the quintessential case study of the power of Op Flinders. It took the group 10 hours to hike 15km on their second day amid howls of protest, demands to return home and many, many tears.

But the group gradually reset to form an “incredible team” with a positive mindset who have, she insists, “smashed it”. “We should be on Ripley’s Believe it or Not – you would never pick this team as capable of being like this, not on Day Two,” she says. “They all feel like they’ve changed. They are more self aware. They’ve grown in confidence in their ability to achieve. It’s really wonderful. It’s powerful stuff.”

Nugent went on her first exercise in 2009 and by the fifth day came to the realisation this was something she was born to do. “I remember thinking this was the most important thing I’d ever done in my life, apart from raising my own children,” she says. “You actually feel like you’re part of the team and you’re part of facilitating this incredible transformation. Just watching it, it’s very powerful, and makes me feel good that I’m helping, somehow.”

The teens from Tango 3 have formed a close bond with Nugent, and there’s a strange mixture of both excitement and regret among them about the prospect of catching the bus home tomorrow.

They are, of course, looking forward to a hot shower, a comfortable bed and being reunited with their phones. They’ll return to their lives with a renewed self belief about what they can achieve in the future, fuelled by a sense of accomplishment based on their experience of the past eight days. And they’ll have a new gratitude and appreciation of things they might have previously taken for granted – from the love of their family to the ability to walk into a pantry and grab a quick snack.

“This experience has been one of a kind,” reflects Woodville High student Calee, 15, as we sit around the campfire on that last night. “It’s something I’ll probably only do once in my life. It’s opened me up to who I am as a person and made me really believe and know who I am. It’s helped me make bonds with such incredible people, and do things that I probably would have never done, which is amazing. It’s just been amazing to sit around a campfire with these beautiful people and just bond over the same thing and get to know yourself.”