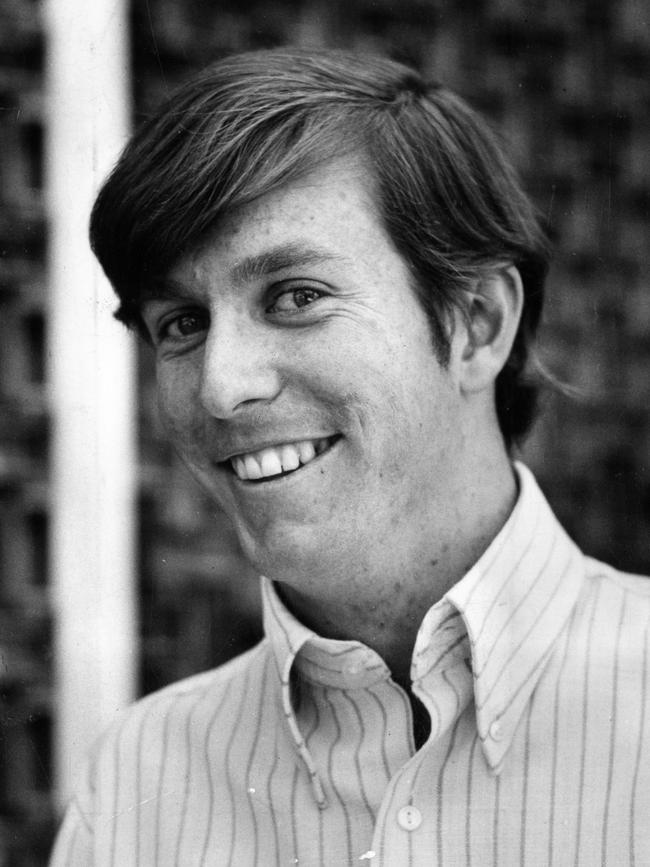

He’s South Australia’s quizmaster, the man behind the hugely popular SA Weekend quiz Brainwaves, but who is Marty Smith?

He’s SA’s quizmaster - the man behind the hugely popular Brainwaves quiz. But who is Marty Smith? LISTEN to this story in podcast form.

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Marty Smith’s Burnside home has more artworks than some galleries, but one piece in particular catches the eye: a dark painting crisscrossed with lines of bright, dripping, lurid colour. It might be a cave. It might be a fierce storm. Up one side climbs a long staircase to a light at the top.

I tell him it looks like Hell.

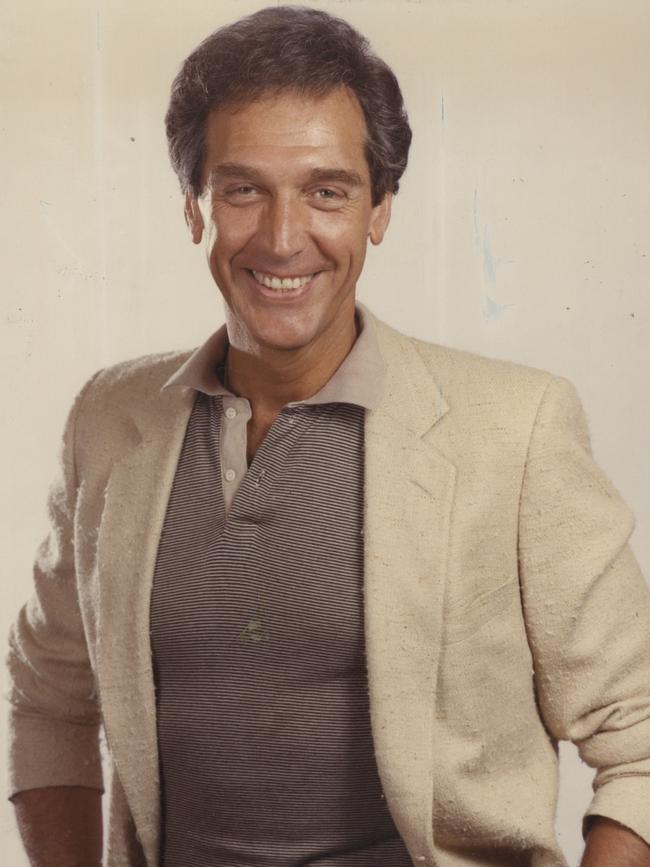

“That is actually my life,” says the 73- year-old who has compiled this newspaper’s and magazine’s Brainwaves column for three decades.

Smith commissioned the work from young SA artist Tom Gibbs a dozen years ago. Over four hours he told Gibbs many private things and then asked him to put his life on canvas. At one point, a bit like those of us who tackle Brainwaves regularly, Gibbs was stumped. Almost in tears he rang to say he couldn’t do it. Smith convinced him he could.

LISTEN TO THIS STORY IN PODCAST FORM

“A lot of people come in here and say ‘I don’t like it at all’,” says Smith. “And that’s fine with me, because it’s not their life. I look at it every day and I still now, 12 years later, see new colours, new images.

“There’s a lot of, believe it or not, happiness. But there’s also, I think like everybody, a lot of sadness. And I’m a great believer in black and white. You know, saint and sinner. I think my life has been full of extremes.”

That seems to be a theme. There are clowns aplenty – he likes them because they are sad on the inside, laughing on the outside. Above his bed is a painting of a man with two faces, one smiling, one weeping. By his office is a ladder twisting up to the light, also painted by Gibbs, that has rungs of barbed wire and a string of coloured lights that for Smith symbolises the joy of the carnival. Yin and yang.

Over an afternoon, Smith shares some of what he calls the roller coaster of his life, from his love of collecting to the depression five years ago that had him weeping on the floor; from his collection of 250,000 theatre programs and 12,000 CDs to rubbing shoulders with the stars of music and TV.

Since 1991 Smith has compiled an estimated 80,000 questions for the Brainwaves quiz. Each Tuesday he dreams up another 50 to test, tease and torture his devoted audience around the state’s breakfast tables and coffee shops.

It seems ironic that a man who failed most subjects other than English at school has assumed the mantle of South Australia’s quizmaster. Yet with Marty Smith – radio pioneer, TV researcher, newspaper columnist, collector, music buff, art lover, lifetime bachelor – at times the greatest puzzle seems to be himself.

MARTY ANSWERS HIS CALLING

Right from the start, Smith loved the sound of his own voice. At five or six he realised he spoke more correctly, more dramatically, than other kids. He also believed he had a calling.

It was the early 1950s, before TV, and Smith would listen to the radio and think the announcers were talking to him. “They’re sending me messages,” he recalls thinking. “And they’re saying, ‘I think you’d be good at this’.”

Douglas Martin Caley Smith was the only child of Margaret and Doug, an accountant descended from Yalumba founder Samuel Smith. They lived in a house with a tennis court in Unley Park, where the young boy was soon pretending to be on the radio himself. He’d cue up a song from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs on the 78 record player, read commercials clipped from the paper, and make his own announcements.

It was a bit weird so he didn’t tell other kids. But privately he’d think: “I’m better than what’s on the radio.”

It was not a passing phase. When transistor radios arrived and the Top 40 came to Adelaide in 1958, the pull of radio became stronger. And Smith’s school results at St Peter’s College in the early 1960s were not going to send him to university.

“I hated school, period,” he says. He rebelled against the algebra, medieval history, and Latin which seemed pointless.

His saving grace was English teacher Michael Wilkins who drove a Karmann Ghia sports car, wore corduroy trousers and played Bob Dylan to the class. “He understood I was a square peg in a round hole and would talk to me privately for a long time, just about what was in my head,” Smith recalls. “He encouraged me to go down the path I wanted to.”

The Top 40 captured Smith, and he came to know every song just by the first note or two. One day at the Royal Adelaide Show, where young disc jockey Bob Francis held a quiz at the 5AD booth, Smith, then in his mid-teens, won an armful of 45s by guessing first every song played.

Francis tried to ban him, but Smith was having none of it and kept winning.

“After, he came over and said, ‘Who in hell are you?’,” Smith says. “I said I was just a schoolboy and he said, ‘No, you’re more than that’.” And I wasn’t backward in coming forward so I said, ‘I think I could help you’, or something like that.”

Francis took Smith back to the station on King William Street on the back of his motorbike, and the teenager sat in a corner with his new records while Francis did his show. “And I thought to myself, ‘I’m not even sure I want to be on the radio, but I’m sure I want to be a part of this’.”

Smith did help Francis, ringing disc jockeys in the US to get titbits for the show. They became lifetime friends and in his later years Francis enjoyed doing Brainwaves with friends over coffee in town each Saturday morning.

Smith left high school after four years and wrote to local radio station 5DN to say he should be hired as a radio announcer. The station agreed and paid him a little over 11 pounds a week while he filled various shifts – and soon had a profitable side-hustle going as well.

It turned out 5DN and Channel 9 in North Adelaide shared a canteen, where the outgoing teen rubbed shoulders with local luminaries like news reader Kevin Crease.

Before long, Nine had asked him to do live voice-overs for the evening news after Crease introduced the reports. It was better pay than at 5DN, which not long after sacked him after he describe the Palais Royal on North Terrace as a “terrible old dump”, prompting threats of legal action.

But by then he’d been talking to 5AD, which promptly hired him and soon sent him to run the station at Mt Gambier where he operated for a year as the sole announcer. “I loved it,” he says. “It was the best radio education you can have.”

Late in 1966 he was back in Adelaide on 5AD on various shows and, still only 20, reading the news. He recalls the Sunday in December 1967 that he told listeners that the nation’s prime minister, Harold Holt, had disappeared swimming off Cheviot Beach on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula.

In 1969, 5AD let him take nine months off to travel the world, doing the odd radio report. “Among other things, I had breakfast with singer Tony Bennett, lunch with the comedian Kenny Everett, and dinner with George Martin, The Beatles’ producer,” he recalls.

On his return, he was given his own Sunday night show called Marty – he’d ditched Martin by then – where he’d do things his own way. One night he’d broadcast an hour-long interview with Australian rock singer Johnny O’Keefe, on another he’d hit the streets during the anti-Vietnam War moratorium marches and intersperse interviews with protesters with snatches of songs.

By 1970 he’d become drawn to television, particularly Channel 9 in Melbourne, which gave him a job interview. Unfortunately, there was nothing in variety TV as he’d hoped, so he took a position at radio station 3AK and thought, “At least I'll be in the building”.

Channel 9 back then was “the MGM of Australia”, home to TV legends like Graham Kennedy, he says. “It was just a wonderful factory of fantasy and I remember driving through those gates and thinking, ‘It doesn’t get any better than this’.”

Two weeks after he started he got a surprise call from O’Keefe who, impressed by the interview they’d done, wanted him to be program director at Sydney radio station 2UW. It’s too late, he told the rock legend, he had committed to Melbourne.

But 3AK was not what he wanted, and after a few months he went overseas again, hoping London might provide new opportunities. But his timing was out, so in 1972 he returned to Adelaide where 5DN eventually made him program manager.

“And I guess I changed the sound of Adelaide radio,” says Smith. The station was old-fashioned, he says, and needed a bomb under it – a revolution. He was keen to light the fuse. “I wasn’t like anybody else who was on the radio,” he says. “I was destined to do something different.”

THE BIGGEST FEATHER IN MY CAP

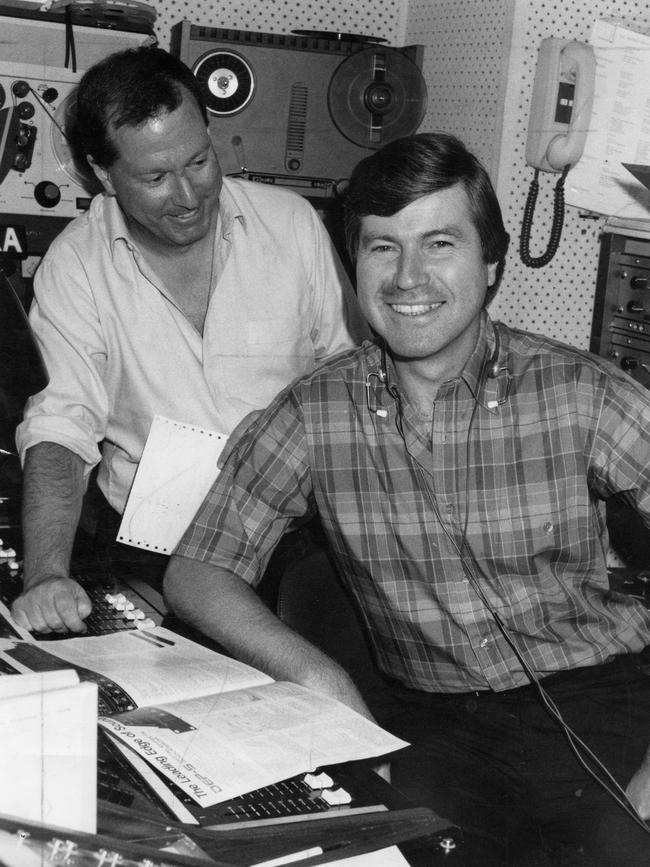

One big move was to bring Jeremy Cordeaux from Sydney, he says. “It needed a big name like John Laws, and Jeremy thought he was John Laws so it worked out perfectly. But I wasn't going to stop there,” he says. “I suppose the biggest feather in my cap was the introduction of sport as entertainment, and putting Ken Cunningham on the radio.”

Cunningham, the former cricketer and footy umpire, was then running the Newmarket Hotel and reluctant to jump into radio. But Smith says he sensed the possibilities – he told his bosses the station was missing out on something big. True, no-one else in Australia was doing it, but that did not mean it was not right.

“It was a gamble that a lot of people thought wouldn't work, because Ken was so raw. Yet I thought he was so loveable … so real, so genuine, passionate, and he worked like a Trojan.”

They started Cunningham with two 30-minute slots a week, and eventually that became the daily drivetime program from 4-7pm. “I remember telling Ken, ‘You’ve only got seven years in this business, make the most of it’. God dammit, he’s still hanging on today.”

Another innovation he claims from the early 1970s is the international phone interview, and one of the first was with Neil Diamond not long after the singer’s Hot August Night album in 1972. “I took it upon myself to do the interview, and we called him in his house in Malibu.

“Neil comes on the line. And my first question was, ‘What kind of parents did you have Neil?’. And his answer was, ‘Well, one was a man and one was a woman’. I thought, ‘My God, this is gonna be hell. This is scheduled for 30 minutes. What’s going to happen?’.”

But Diamond warmed up and the interview went well in the end. Smith no longer has it. Fifteen years ago he listened to his tapes one last time and got rid of them.

Smith says he’s never been a big one for researching what people want. “I believe in gut feeling,” he says.

It worked for 5DN which he says “had phenomenal ratings” as a result. But, that job done, he thought he’d try again with TV, this time Seven in Sydney in 1980. A job was offered in TV, but it did not work out. “It was made impossible,” he says. “You know, it’s television … it’s nasty.”

On the sidelines, he’d been catching up with Mike Willesee whose production company operated out of Seven. The pair got on well at a time when Willesee was struggling against the barnstorming Sale of the Century. “He said, ‘Why don’t you come and help me?’” says Smith, who agreed and worked with Willesee for about three months. When Derryn Hinch was flown daily up from Melbourne to replace Willesee for a time, Smith tried to help him too. Again, it just didn’t happen.

He insists the failure of his attempt to climb the TV ladder didn’t bother him.

“I knew I hadn’t achieved that, but that didn’t consume me,” he says. “Not at all. Because I’m a great believer that you’ve got to be down to come up. You’ve got to be happy to be sad. Some people don’t have that opportunity. I do.

“My life is a roller coaster. Not so much now because it’s so locked in what I do. Then, I was young. So you’re knocked down one day and you’re up the next day. And part of me was fulfilled because I was in the building.”

While he laments the loss of live variety TV, he did meet some of the masters. There was the lanky yank Don Lane, who knew how to make people feel special, he says. He recalls how two years after he met the American, Lane spotted him in a foyer and called out “How ya doin’ Marty!”, instantly remembering him.

His idol was Graham Kennedy, a notoriously reluctant interviewee. The pair met in the office of entrepreneur Harry M. Miller who had promoted the controversial musical Hair. “And Harry said, ‘Oh, you must talk to him’. I said, ‘Oh, OK’. You know, I wasn’t expecting him to be there. And he obviously called Graham over. I can’t remember what Graham’s reaction was, but he probably said, ‘F..k you, Harry’. And, anyway, Harry had the last say, and Graham and I sat down, and we talked for half an hour.”

He knew Mike Walsh well before his long-running daytime TV show. Walsh was on radio in Sydney when Smith, then 17, managed to get into the 2SM studio to watch him on-air in 1964.

The pair hit it off and for years Walsh would send a handpainted Christmas card, and Smith remembers the repeated message: Whatever you do, keep killing ‘em. “And I took that to heart,” Smith says.

He knew Adelaide Tonight host Ernie Sigley too, who later married the winsome Glenys O’Brien. Well before then, Smith recalls seeing O’Brien before she left to work overseas in 1965.

“We were crossing the street. I just said to Glenys, ‘All the best for the trip’. And she said, ‘Come here, I want to hug you forever!’. And in the middle of Tynte Street, we had this enormous pash. And I kid you not, I can still feel it to this day.”

But Smith never married.

“How do you explain these things? I don’t think you need to,” he says. “The simple way is to say, ‘I was married to my job’. And I think that was a big part of it because I started so young.”

A NEW DOOR OPENS

After he left Willesee at the end of 1981, Smith decided to work for himself in Sydney. “I was sick of being pushed around by other people,” he says. So he entered the world of print with a newsletter he flogged around the industry for a yearly subscription of $95. It had a bit of gossip and also facts about daily events. His first subscriber was Bert Newton.

Smith soon realised he could do the newsletter from anywhere, so headed back to Adelaide where he broadened his print media involvement.

By 1987 his column of snippets for The Advertiser, once called On This Day, now The Last Word, had started. He says he can’t find a longer-running daily column in any newspaper around the world.

Then, in 1991, someone had the idea he might do a quiz. He thought he could at least have a go, and soon Brainwaves was born – although his name was not regularly attached until SAWeekend began in 2009.

Smith says he has no secret formula for his questions, which he draws from an array of sources such as his clippings from a garage-full of old newspapers, reference books, and the internet.

“It’s a dog’s breakfast,” he confesses. “There’s no format. It’s what I’ve read and what I've looked at, what I’m interested in, and what I think people are genuinely interested in.”

Some questions are insanely easy. What letter follows L? But the simple ones are leavened by the difficult, especially for those who haven’t studied favourite themes like the periodic table of elements, the solar system, hits from the musicals (several times he’s seen 25 Broadway shows in 25 days) and dogs in old TV shows.

There are also occasional Neighbours questions. He spent 15 years watching that show and Home And Away, taking detailed notes with a plan, abandoned, to write a couple of books. Naturally, he has a story about Kylie Minogue and Jason Donovan – who, after they were mobbed by fans at Radio 5KA’s show stand in 1986, he helped smuggle away in a windowless panel van.

So what is a good score? “If you do it as a family or a group, it seems to me you usually get around 35,” he says. “If you do it as an individual, you’re around 25.”

Some questions don’t have answers though. Smith has no idea why, five years ago, he was hit with depression.

“It was awful,” he says. “I don’t know what caused it.”

Had it not been for the need to do his columns and quiz, “I would have stayed in bed all day,” he says. Sometimes he’d end up on the floor crying, saying “All right, they’ll find me.”

“You cry for no reason at all,” he says. “I never knew I had so many tears in me.”

He credits his GP, who took the time to talk extensively with him, for getting him through.

“I’ve talked about it to a lot of people and everybody seems to have different stories about depression – everybody,” Smith says.

It lasted eight months, and he recalls the moment he knew he’d be OK, watching TV one Sunday morning. “I thought, something is going to happen, it will be better,” he says. It did lift a month later, although, he thinks, you always have it a little bit.

These days, he’s back on track. He’s cleared a lot of clutter from his house – “I’m not a hoarder, I’m a collector”. He’s arranging his 12,000 CDs in alphabetical order. His quarter of a million theatre programs dating back to 1840 are also being organised. He’s got 70,000 hits downloaded in his bid to have every hit from 1940-1989.

And he finds more each day to see in that painting of his life. I ask him about that staircase. Which way is he heading now – down into the dark or up to the light?

“Going up,” he says firmly. “There’s still some salvation at the end, I’m hoping.”

Test your skill in this week’s Brainwaves quiz.