Harry “Breaker” Morant: Inside the new bid to pardon the convicted Boer War criminal

He admitted ordering the execution of 12 people, including boys, during the Boer War. So why is a new bid to clear the name of Harry “The Breaker” Morant gaining momentum?

SA Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from SA Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Somewhere beneath the headstone which sits atop his modest grave in Pretoria’s Church Street Cemetery, Harry “The Breaker” Morant must be quietly doing cartwheels.

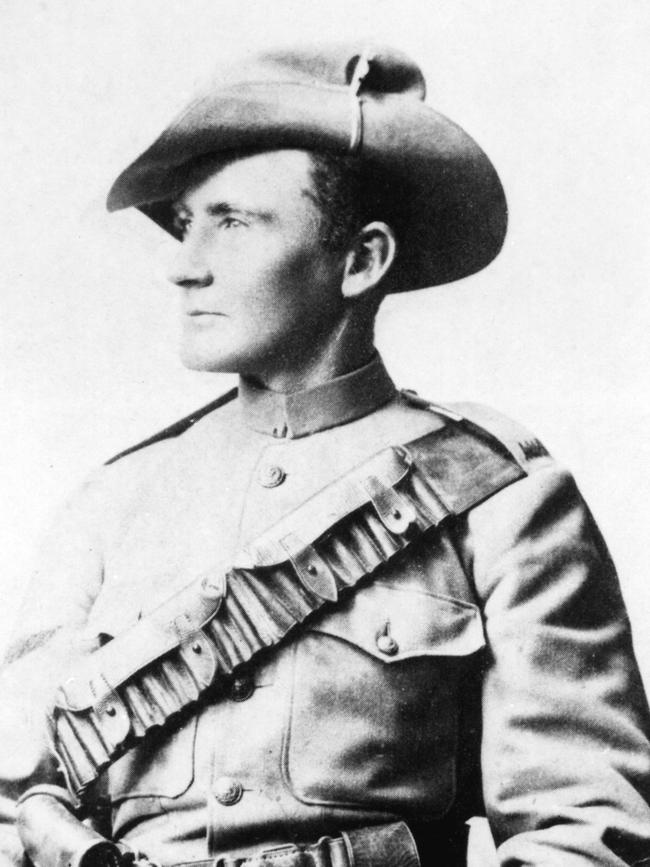

Because Morant, Australia’s most famous convicted war criminal, is back in the headlines – almost 120 years after his conviction and execution for shooting Boer prisoners.

It’s a conversation and a controversy that Morant, no doubt, would have enjoyed. Firstly, and most obviously, the debate provides a chance to clear his name from the guilty verdict which sent him and fellow lieutenant Peter Handcock to the firing squad.

But that’s not the only reason Morant would be delighted his name is back in the newspapers. The Breaker was a master of the written word. A regular contributor to the annals of early Australia. And he was never one to shy from the limelight, nor to downplay his own abilities.

In fact, Morant spent most of his adult life carefully curating an identity as a bush balladeer, journalist and raconteur. As one author on the myriad books which have been written on the topic wrote: “Most people have to wait for their legend to be created at the hand of others, but ‘The Breaker’ simply wrote his own.”

So it’s not too much of a stretch to deduce that the thought of returning to the national consciousness would sit more than comfortably with the bushman and buccaneer who was executed on February 27, 1902 after being found guilty of killing 12 prisoners towards the tail end of the Boer War.

Whether the men and boys (one was as young as 12) he ordered killed were prisoners or innocent civilians remains a point of great contention, but more on that later.

The debate is back in the spotlight because military lawyer James Unkles is reigniting his bid for the Australian government to launch an independent inquiry into what he calls the “fundamentally flawed” processes involved in the series of British courts martial which led to the Morant and Handcock executions. A third soldier, lieutenant George Witton, was also tried and sentenced to death, but that sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, of which he served less than three years before being released.

Morant, though once briefly married, never had children so has no direct descendants but shares an ancestor with Cathie Morant, who backs Unkles’ push for an inquiry and is also leading the family charge for his name to be added to the Adelaide Boer War Memorial on North Terrace.

“It’s not right that they’re still being victimised like this,” Cathie Morant tells SAWeekend down the line from her home in Canberra. “They deserve to be recognised for the service they have provided.”

Unkles and Cathie Morant have written to both premier Steven Marshall and Adelaide City Council asking for The Breaker’s name to be included on the historic memorial. But again, more on that later.

Unlike Morant, Handcock left behind a wife and three young children, and his great grandson Michael Handcock says the stigma and shame of his ancestor’s conviction and execution has had a profound impact on his family.

“I don’t remember my grandfather, who was Peter Handcock’s son, but my dad said he was very affected by it,” Michael Handcock says from Sydney. “He lived his whole life essentially in shame, because he thought his father was a murderer. So I just look at my own kids (who range in age from 15 to 21) and think ‘how would they feel if it was me?’ If they (Morant and Handcock) were wrongly convicted and wrongly executed, it’s just such a tragedy.

“It’s a moment that can’t be taken back, and it is what it is, but part of me feels like it should never have happened, and (if it had not) my grandfather’s life would have been very different.

“And I think my own father’s life was affected by it because his father was such an angry person all his life.”

Angry. It was the primary emotion of Morant when he heard that enemy Boers had shot and killed the man he described as his “best friend”, Captain Percy Hunt, on August 5, 1901. Well, furious is probably closer to the mark. Apoplectic even more accurate.

Morant is a polarising figure among historians. Some portray him as a bloodthirsty psychopath who went out of his way to shoot unarmed Boer farmers who had surrendered of their own free will. Others say he was a charismatic larrikin, wrongly framed for carrying out British orders to take no prisoners.

But most agree that the catalyst for the turn of events which led to his execution seven months later was the fire of rage lit when he learnt of Hunt’s death. Morant himself admitted as much when he told his court martial that he had ignored orders to “not bring in prisoners” until his “best friend was brutally murdered”.

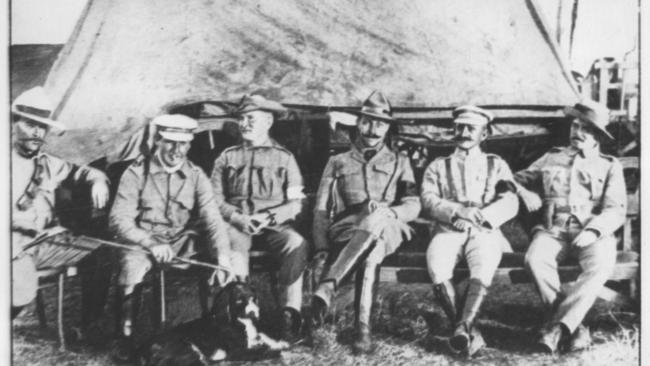

Hunt and Morant had been members of the relatively new Bushveldt Carbineers – a regiment of irregular mounted infantry raised as part of a British plan to overcome an enemy which had proven disturbingly difficult to finish off.

The Boers had enjoyed first blood when conflict exploded in October, 1899 after the discovery of diamonds and gold in the independent Boer states of Orange Free State and the Transvaal, in modern-day South Africa, had sparked British interest.

Britain refused an ultimatum to remove their troops from the borders which separated Boer and British territories. So the Boers, Afrikaans-speaking farmers descended from the Dutch and Germans who settled in southern Africa in the 1600s, attacked British strongholds of Ladysmith, Mafeking and Kimberley in northern Natal. The outbreak of war sparked a patriotic passion in Australia, where the six colonies of NSW, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, Tasmania and Western Australia were on the verge of becoming one nation.

Men signed up in their thousands to their colonies’ newly raised fighting units to help Mother England and among them was 35-year-old Harold “The Breaker” Morant, who enlisted with the South Australian Mounted Rifles Second Contingent.

Morant had been born in England in 1864 as Edwin Henry Murrant, the son of a widowed matron of a workhouse for the poor in Bridgwater, Somerset. He would later claim to be the illegitimate son of Sir George Digby Morant, an admiral in the British navy. Digby Morant denied this was the case but young Edwin Murrant enjoyed an expensive education despite his mother’s poverty, a fact which some historians say back up the younger man’s lineage claims.

Murrant arrived in Australia in 1883, settled in northern Queensland (well, settled is perhaps the wrong word, for he was the ultimate drifter) and married a young Irish woman called Daisy O’Dwyer in Charters Towers, inland from Townsville, the following year. The marriage lasted just weeks. (O’Dwyer, incidentally, would go on to become the renowned welfare worker, anthropologist and Aboriginal culture expert Daisy Bates, who died in Adelaide and is buried in Nailsworth’s Main North Road Cemetery.)

Not long after his marriage dissolved, Murrant assumed the name Henry Harbord Morant and he spent the next 15 years wandering across Queensland, NSW and SA, earning a reputation as a charismatic expert horseman and talented boxer with a bank balance which was never able to match his extravagant lifestyle. He became known for being able to break in even the most difficult horses, and hence earned the moniker The Breaker, which he used as pen name for regular poetic contributions to numerous publications, including The Bulletin.

He was a contemporary and sometime friend of acclaimed bush poet and journalist Banjo Paterson who wrote of his former rival: “Morant lived in the bush the curious nomadic life of the Ishmaelite, the ne’er-do-well … (He) was always popular for his dash and courage, and he would travel miles to obtain the kudos of riding a really dangerous horse.”

Paterson said The Breaker was also “a spendthrift and an idler, quick to borrow and slow to pay” who made a habit of avoiding steady employment. But, he wrote: “The idea that he would take or order the taking of the life of an unarmed man for the sake of gain is utterly inconsistent with every trait of his character.”

When war broke out in South Africa, Morant was living in Renmark and he travelled to Adelaide to sign up with the SA Mounted Rifles.

Historians agree that Morant served the SA regiment with distinction, earning promotion to sergeant and praise from his commanding officer. When his six-month term of enlistment ended he set sail to his homeland of England in search of greener pastures but returned to South Africa in early 1901, where he scored a commission as a lieutenant with the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC).

By this stage, the British had recovered from those early setbacks in Natal and were in control of the war, having captured the Boer settlements of Pretoria and Johannesburg. But the conflict had reverted to guerilla warfare and the frustrated British leadership established mobile units such as the Carbineers, manned primarily by Australians, to combat a desperate and innovative enemy.

On August 5, 1901, Morant’s great mate Percy Hunt led an ill-fated patrol which attacked a Boer-held farm hut and his subsequent death elevated Morant to command and set in trail a thirst for revenge which led to the death of at least 12 Boers in at least three separate incidents over the next month. Morant and Handcock were also charged with killing German missionary Daniel Heese – but found not guilty.

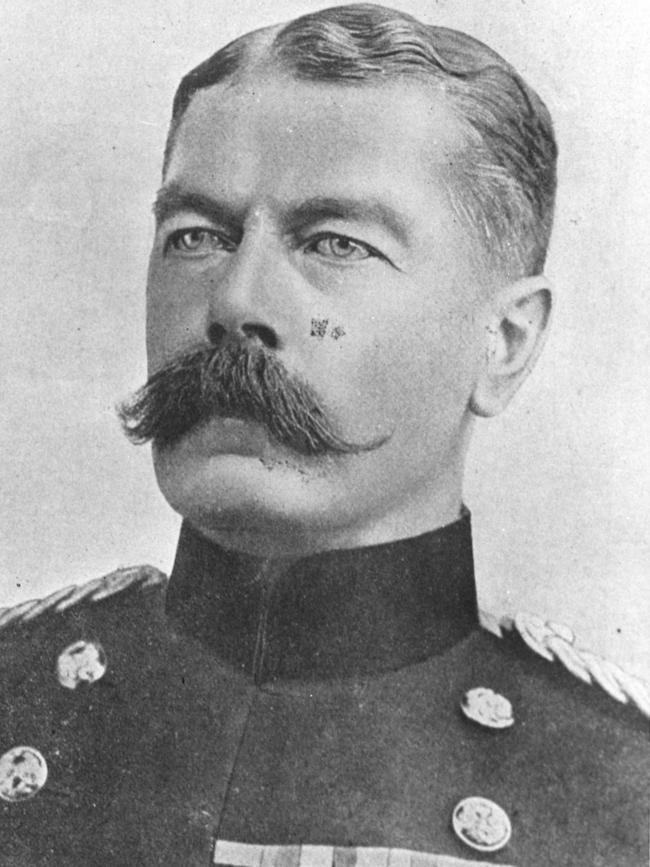

Morant, Handcock and Witton never denied killing the Boers. But they pleaded not guilty to the murder charges, claiming they were under orders from the commander in chief of the British army in the war, General Lord Horatio Kitchener, to take no prisoners.

They were unable to provide proof of such orders and after five weeks of courts martial were found guilty of murder or manslaughter. Every murder verdict came with a sentence of death by firing squad, but also with a recommendation for Kitchener, who needed to sign off on the death sentences, to show mercy.

But the hard-line Kitchener, infamous for sending Boer women and children to the world’s first concentration camps (in which nearly 50,000 people perished) granted clemency to just Witton, sending Morant and Handcock to their graves.

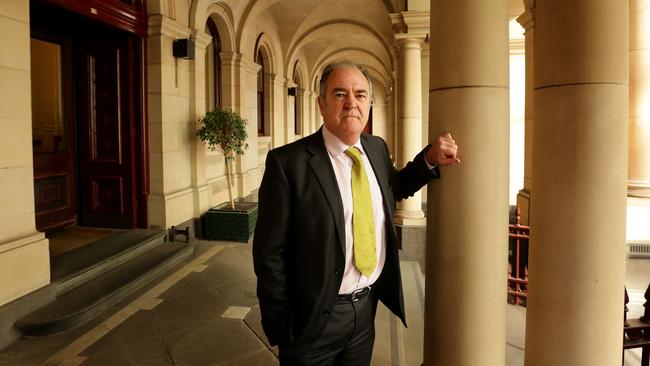

Unkles, the Melbourne-based military lawyer who has campaigned for more than a decade for posthumous pardons for the men, says there were numerous flaws in their arrests, investigation, trial and sentencing.

“There has never been any doubt that Morant, Handcock and Witton were involved in the shooting of prisoners,” he says. “My advocacy is not about excusing murder, it’s about the sanctity of the rule of law and trial according to due process of 1902.

“These men were not tried in accordance with military law and procedure of 1902, and suffered great injustice as a result. The convictions were unsafe and the sentences illegal, as appeal was denied and due process seriously compromised.”

Unkles points to the fact the men were denied details of the investigation into the killings and denied legal advice until the night before their trials. He says the prosecution had three months to prepare its case while the trio’s lawyer, Major James Thomas, a solicitor from country NSW with no military law experience, was appointed the day before the trials began.

Furthermore, says Unkles, the trial process contained serious legal errors by both the judge advocate overseeing the courts martial and Kitchener himself.

“The brutality of the Boer War in British military history is something many, particularly in London, would rather forget,” says Unkles, who has written a book about Major Thomas. “In the midst of that struggle, the trial of these three volunteers highlighted reprehensible tactics ordered by British officers, including reprisal through summary execution as a means of prosecuting the war.

“It has been argued convincingly with persuasive evidence that the Australians shot 12 Boers while acting under the orders of senior British regular army officers, including Lord Kitchener.

“Putting that aside, the legitimacy of the process used to try these men was illegal and improper, and was done to hide the criminal culpability of British officers. Put simply, the accused were not afforded the rights of a person facing serious criminal charges enshrined in the military law and procedure of 1902.”

Immediately after commuting Witton’s sentence, Kitchener made himself uncontactable, a move which, Unkles says, denied the pair their right of appeal to the King. The British military hierarchy in South Africa also failed to inform the New Australian government of the proceedings until after Morant and Handcock had been executed.

Midway through their trials, Morant, Witton and Handcock were temporarily released from their cells and helped the British defend Pietersburg from a Boer attack – action which Unkles says should have sparked pardons under the old military custom known as condonation.

And Unkles says he has uncovered new evidence, from the case book of British Judge Advocate-General Colonel James St Clair, of orders from British officer Captain Alfred Taylor to take no prisoners. Historians agree that Taylor, nicknamed ‘Bulala’ (Killer) by native Africans, was one of the genuine villains of the whole Breaker Morant saga.

Unkles put this new evidence, and his case against the legality of the 1902 courts martial, to a moot hearing of the Victorian Supreme Court in 2013. The proceedings carried no legal standing, but senior counsel acted for both the Crown and the accused and senior barristers Andrew Kirkham and Gary Hevey acted as presiding judges.

The moot hearing found unequivocally that Morant, Handcock and Witton had not received proper trials and suffered a substantial and fatal miscarriage of justice. Unkles has petitioned both the Australian government and the Queen to provide posthumous pardons for the trio, but has had no success.

His mission now is for the Australian government to open an independent inquiry into the events of 120 years ago and, over the past decade, he has built a list of politicians and lawyers who are backing the call. Legal luminaries who have voiced their support include Geoffrey Robertson, Gerry Nash, David Denton, Sir Laurence Street (deceased), Alexander Street and former SA chief justice Dr Howard Zelling (deceased).

An extract from Robertson’s legal opinion reads: “They were treated monstrously. The case of Morant and Handcock, the two men who were executed, is a disgrace. Certainly by today’s standards they were not given any of the human rights that international treaties require men facing the death penalty to be given. But even by the standards of 1902 they were treated improperly, unlawfully.”

The list of federal politicians who have backed Unkles’ case includes Immigration Minister Alex Hawke, Health and Aged Care Minister Greg Hunt and former attorney general Robert McClelland. Former deputy prime minister Tim Fischer was vocal in his support before his death in 2019 while current Nationals leader Barnaby Joyce and maverick Queensland MP George Christensen are also on board.

But the support for Morant is by no means universal. Many historians are simply unable to forgive the acts of violence to which he admitted. As Morant famously said under cross examination, in a line immortalised in the classic 1980 Bruce Beresford movie starring Edward Woodward as Morant, Bryan Brown as Handcock and Jack Thompson as Major Thomas: “We got them, and we shot them under rule 303.” He was referring, of course, to the soldiers’ .303 rifles.

Best-selling author Peter FitzSimons leaves the reader in no doubt about his views in the popular book he published last year. “All up I think that Breaker Morant and Peter Handcock got exactly what they deserved,” FitzSimons writes on the 500th and last page of his book.

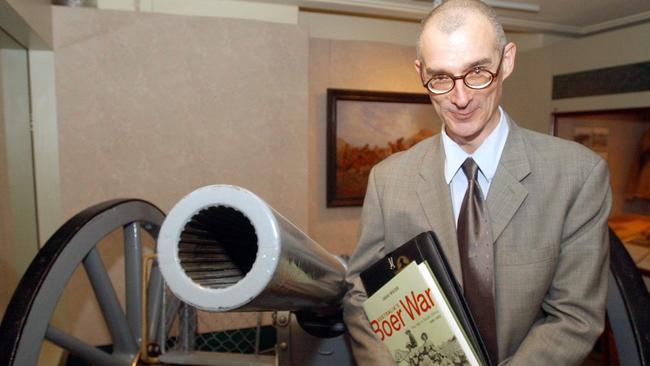

It’s an opinion shared by Sydney historian Craig Wilcox, author of Australia’s Boer War, a book recognised as offering the definitive history of Australia’s involvement in the South African conflict.

“You could sum it up by saying Morant and the other defendants aren’t the victims here – the victims were the men and teenagers, white and black, who were mercilessly and pointlessly killed in cold blood,” Wilcox tells SAWeekend. “It’s hard to see why an independent inquiry is needed when the key facts found in the original trials don’t leave a lot of wiggle room.

“The accused denied committing only one of a dozen murders. The mythical secret orders to commit the murders have never been found, and if they really were issued, they would have contradicted military law. In all but one case, the murders were of civilians, not prisoners of war.”

Wilcox says the three men were given a lawyer of their own choosing and were court martialled over a five-week period in an era when murder trials typically lasted just three days. And he says the Australian government had no jurisdiction in the case because the Bushveldt Carbineers was a British regiment.

Morant, Handcock and Witton found themselves in front of that court martial because a group of 15 fellow Carbineers signed a letter sent to the British high command in South Africa accusing Morant et al of “disgraceful incidents”

The incidents in question included: “the shooting of six surrendered Boer prisoners who had been entirely disarmed and offered no resistance whatsoever … the shooting of Trooper van Buuren BVC by Lt Handcock BVC … the shooting of a surrendered and wounded Boer prisoner, Visser … shooting eight surrendered Boer prisoners and one German missionary … killing two children of tender years … shooting two men and a boy who were coming in to surrender.”

The letter continues: “We cannot return home with the stigma of these crimes attached to our names. Therefore we humbly pray that a full and exhaustive inquiry be made by Imperial officers in order that the truth be elicited and justice done.”

One of the signatures on the letter belonged to Trooper Arthur Wyatt Miles Thompson, who was also called as a witness at the court martial trial into the shooting of Boer farmer Roelf van Staden and his sons Roelf Junior, 16, and Christiaan, 12.

Thompson went on to serve with distinction in World War I, receiving a Military Cross for his gallantry in Palestine in 1917. He returned to become a highly respected farmer and community leader in Dumbleyung, southwest Western Australia and a revered figure among his family and friends.

His great nephew Alan Thompson lives in Woodside in the Adelaide Hills and says he is confident that Morant should continue to be remembered as a war criminal.

“If my great uncle wrote a letter in condemnation seeking a court martial for Morant, knowing his later history and character and so on, then everything that has happened to Morant was probably justified,” he says. “I don’t think we should honour him any further – I think he did enough to disgrace himself.”

Tony Stimson is the president of the SA Boer War Association and is leading the case against adding Morant’s name to the historic Adelaide memorial which currently lists 60 SA men who died in the Boer conflict. Stimson’s passion for the Boer War is understandable and perhaps unrivalled. His grandfather Alfred Norton was a captain in the SA Mounted Rifles and, in 1900, was involved in a ferocious skirmish near the township of Vredefort, in Orange Free State.

On July 24, Norton was one of 16 men besieged in a mud hut after seizing five convoys of precious Boer flour. Three of his men were killed by enemy fire. One bullet grazed Norton’s skull, passing close enough to singe his hair, but it did not penetrate the skin. Another bullet hit the heel of his boot. Again, he was not injured.

And then, as he was attempting to flee on horseback, his steed was shot from under him. The horse tumbled to the ground, dead, squashing Norton’s legs in the fall. (On that same day, less than 100 metres from where Norton was trapped under his horse, fellow soldier Lieutenant Neville Howse was in the process of becoming the first Australian to win the nation’s highest military accolade, the Victoria Cross, when he defied heavy enemy fire to help a wounded colleague to safety. Howse would go on to serve with distinction in WWI, becoming a major general. He was later knighted and became a minister in the cabinet of Prime Minister Stanley Bruce.)

Norton returned to Australia to recover from his series of miraculous escapes and in 1907 became a proud father to Mary who, in 1949, became Tony Stimson’s mother. And so Stimson is the first to admit he’s lucky to be here. Had any of those bullets been a centimetre closer to his grandfather, the family line would have ended then and there.

Stimson has travelled to South Africa on several occasions to learn about the Boer War and visit the places his grandfather was lucky to survive.

He delivers presentations on Morant to historical groups and is the foremost authority on the Adelaide Boer War Memorial, which was unveiled in June 1904 on the corner of North Tce and King William St. The memorial consists of a magnificent life-size bronzed statue of a soldier on horseback perched atop a 3.7m-high Murray Bridge Granite pedestal.

“I don’t think it’s a case that you can say that if he served, therefore he should be invariably recognised,” Stimson says.

He points to the fact that the memorial received no government funding and relied on public donations, which included pledges as small as a sixpence from women and children.

There is also no recorded debate about including Morant’s name on the original list, despite his death being perhaps the most public of any South Australian who served in the Boer War.

“What are they (those women and children) going to think about having a man added to the memorial, by a later generation which thinks it knows better, whose record is really rather seriously compromised – particularly the shooting of the van Staden children,” Stimson says.

“I think we need to be a bit more respectful to the past. People at the time were in a better position to know and they made certain decisions, and they made them in good faith.”

Stimson also points to the fact that the South African War Veterans’ Association, which formed soon after the war and dissolved in 1972, never lobbied to have Morant’s name on the memorial.

“My point is, for almost 70 years, the veterans of the war, including many men who had fought with Morant in the second contingent, had abundant opportunities to say Morant also deserved to be there,” Stimson says. “But their silence is deafening. They just did not want him there. Frankly, I don’t think there are any decent arguments.”

On the other side of the Indian Ocean, Morant’s name holds far less mystique. KwaZulu-Natal based historian Robin Smith says most South Africans would never have even heard of Morant, despite the ‘fixation’ of many Australians.

“But as a person, Breaker Morant was a dreadful fellow,” Smith says. “He was one of those rascal guys who would continue on around the country and bounce cheques and leave debts behind him.

“I don’t know what the word is really, but he’s not the sort of fellow that should be made into a hero. In my opinion, he got what he deserved.”

And so it appears that James Unkles and the descendants and relatives of Morant, Handcock and Witton face a long road ahead in their bid to clear their collective names – a road peppered with the potholes of passionate objectors.

In retrospect, perhaps those metaphorical cartwheels taking place under the gravesite The Breaker shares with Handcock in Pretoria are on hold. For now.